Metoo in Surgery Narratives by Women Surgeons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Bystander Intervention Handout

WHAT IS HAZING? Based on the definition provided, when does an activity cross the line into hazing? The following three components of the hazing IS... definition of hazing are key to understanding hazing: “Hazing is any activity 1. Group context | Hazing is associated with the process of joining expected of someone and maintaining membership in a group. joining or participating 2. Abusive behavior | Hazing involves behaviors and activities that in a group that are potentially humiliating and degrading, with potential to cause humiliates, degrades, physical, psychological and/or emotional harm. abuses, or endangers 3. Regardless of an individual’s willingness to participate | The “choice” to participate in a hazing activity is deceptive because it’s them regardless of a person’s willingness to usually paired with peer pressure and coercive power dynamics that (Allan & Madden, 2008) are common in the process of gaining membership in some groups. participate.” Circumstances in which pressure or coercion exist can prevent true (Allan & Madden, 2008) consent. WHAT MIGHT HAZING LOOK LIKE? • Ingestion of vile substances or concoctions • Being awakened during the night by other members • Singing or chanting by yourself or with other members of a group in public in a situation that is not a related to an event, game, or practice • Demeaning skits • Associating with specific people and not others • Enduring harsh weather conditions without appropriate clothing • Being screamed, yelled, or cursed at by other • Drinking large amounts of alcohol to the point of members getting sick or passing out • Wearing clothing that is humiliating and not part • Sexual simulations or sex acts of a uniform • Sleep deprivation • Paddling or whipping • Water intoxication • Forced swimming REMEMBER: Hazing is not necessarily defined by a list of behaviors or activities. -

Confronting the Epidemic of Mental Illness in the Legal Profession

The Other Silent Killer: Confronting the Epidemic of Mental Illness in the Legal Profession Presented by James P. Carlon, Esq. 1 The Roadmap Identify the problem and its general causes Identify and analyze the particular issues of the legal profession as a causative factor Identify solutions CAUSES OF MENTAL ILLNESS • Hereditary Factors • Physical Trauma • Environmental Factors* Source WebMD https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/mental- health-causes-mental-illness#1 3 Symptoms Changing normal routine (i.e. eating and sleeping) Self-isolation* Mood swings Feeling trapped and hopeless about a situation Cognitive dysfunction Source: Mayo Clinic www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/suicide-symptoms Common Risk Factors • 1. Family History • 2. Stressful life situations* • 3. Alcohol or drug use • 4. Social Isolation and Lack of Relationships • 5. Traumatic Experiences Source: Mayo Clinic 5 Why are lawyers at such high risk for Mental Illness? Profession Specific Issues Vulnerable Population Preponderance of Common Risk Factors Lack of Emphasis on Mental Health and Wellness Toxic Policies Toxic People Lawyer Vulnerabilities Perfectionism Highly competitive Pessimism Validation seeking Client-focused life 8 Preponderance of Risk Factors Higher than average stress (1990 Johns Hopkins University Study examining more than 100 occupations showed lawyers 3.6 x more likely to be depressed than other occupations studied). 21% of licensed, employed lawyers qualify as a problem drinker(2016 Study-Hazelton Betty Ford Foundation and the American Bar Association) 9 Fear. Obligation. Guilt 10 Lack of Attention and Emphasis on Mental Health Problem of stigma exacerbated by business concerns Lack of readily accessible, or on-site counseling to employees and staff Seen as an outside problem Choose language Toxic Policies Toxic: “ Causing or capable of causing death or illness if taken into the body” Source: www.Meriam-Webster.com 12 The Prime Directive for Young Lawyers “Don’t focus on business development. -

Assessing the Efficacy of Analytical Definitions in Hazing Education

Assessing the Efficacy of Analytical Definitions in Hazing Education by Paul Robert Kittle, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 8, 2012 Keywords: hazing, definition, cognitive, extensional, analytical, bystander Copyright 2012 by Paul Robert Kittle, Jr. Approved by David C. DiRamio, Chair, Associate Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology James E. Witte, Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology Maria Witte, Associate Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership and Technology Abstract Hazing is a problem that persists on college campuses and in high schools. According to Nuwer (2011) between 1970 and 2006, there was at least one hazing-related death each year on a college campus. Hazing education and prevention programs, such as speaker series, anti-hazing marketing campaigns, policy enforcement efforts, and sanctioning, which are frequently grounded in an extensional definition of hazing, have been present on college campuses for the past 20 years, yet the incidents of hazing are on the rise (Ellsworth, 2006; Nuwer, 2004). The literature repeatedly states that, due to the lack of a common definition, awareness and prevention efforts are often unsuccessful at increasing students’ awareness of hazing activities or reducing the likelihood that hazing activities will occur (Allan & Madden, 2008; Ellsworth, 2006; Hollmann, 2002; Shaw, 1992; Smith, 2009). Allan and Madden (2008) found that 91 percent of students who have experienced hazing do not identify themselves as being hazed. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether or not there were differences in students’ ability to identify hazing activities after treatment which consisted of reading either an extensional or analytical definition of hazing. -

January 16, 1989

tressing: Classes, activities get to students 14 THURSDAY, JANUARY 19, 1989 JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY VOL. 66 NO. 30 Sprint splash 'Scream' JMU population is getting too big By Wendy Warren staff writer A group of JMU students, angry about what they say is a threat to the university's identity, plans to fight what they consider uncontrolled enrollment growth. The Student Committee to Review Enrollment at Madison (Scream) wants to keep enrollment at a level JMU can handle, said founder Stephan Fogleman, who also is secretary of the Student Government Association. "The reason I chose JMU was that it was not too big and not too small," Fogleman said. "But [JMU] is real close to losing that attractive feature." The overcrowded conditions have made JMU impersonal, and "almost like a corporation now," he said. Scream's members consist of JMU sophomores and freshmen who are active in the Student Government Association, since "these arc the people who will Staff photo by LAWRENCE JACKSON have to deal with the enrollment issues," Fogleman A runner treks along JMU's rain-streaked track Sunday afternoon. said. Most seniors who are active in campus politics are too busy to solve JMU's long-term problems, he said. "It's what will happen over the next four years Students vary on hazing views that worries me." Within the next week, the group will circulate a petition against increasing JMU's current enrollment, By Rob Morano presented to about 45 greek organizations nationwide, assistant editorial editor he attempts to define hazing and its dangers. Fogleman said. -

The Political Construction of Collective Insecurity: from Moral Panic To

Center for European Studies Working Paper Series 126 (October 2005) The Political Construction of Collective Insecurity: From Moral Panic to Blame Avoidance and Organized Irresponsibility by Daniel Béland Department of Sociology University of Calgary 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 1N4 Fax: (403) 282-9298 E-mail: [email protected]; web page: http://www.danielbeland.org/ Abstract This theoretical contribution explores the role of political actors in the social construction of collective insecurity. Two parts comprise the article. The first one briefly defines the concept of collective insecurity and the second one bridges existing sociological and political science literatures relevant for the analysis of the politics of insecurity. This theoretical framework articulates five main claims. First, although interesting, the concept of moral panic applies only to a limited range of insecurity episodes. Second, citizens of contemporary societies exhibit acute risk awareness and, when new collective threats emerge, the logic of “organized irresponsibility” often leads citizens and interest groups alike to blame elected officials. Third, political actors mobilize credit claiming and blame avoidance strategies to respond to these threats in a way that enhances their position within the political field. Fourth, powerful interests and institutional forces as well as the “threat infrastructure” specific to a policy area create constraints and opportunities for these strategic actors. Finally, their behavior is proactive or reactive, as political actors can either help push a threat onto the agenda early, or, at a later stage, simply attempt to shape the perception of this threat after other forces have transformed it into a major political issue. -

Toxic Leadership and Voluntary Employee Turnover: a Critical Incident Study

Toxic Leadership and Voluntary Employee Turnover: A Critical Incident Study By Richard P. March III B.A. in German, May 2002, Franklin & Marshall College M.A. in German and Second Language Acquisition, May, 2005, Georgetown University A Dissertation Submitted to The Faculty of The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education May 17, 2015 Dissertation Directed by Neal Chalofsky Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning The Graduate School of Education and Human Development of The George Washington University certifies that Richard P. March III has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Education as of February 24, 2015. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Toxic Leadership and Voluntary Employee Turnover: A Critical Incident Study Richard P. March III Dissertation Research Committee Neal Chalofsky, Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning, Dissertation Director Maria Cseh, Associate Professor of Human and Organizational Learning, Committee Member Thomas Reio, Professor of Adult Education and Human Resource Development, Florida International University, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2015 by Richard P. March III. All rights reserved. iii Abstract of Dissertation Toxic Leadership and Voluntary Employee Turnover: A Critical Incident Study Contributing to the burgeoning corpus of literature examining the deleterious impacts of toxic leadership upon employees and organizations, the present study utilizes 15 study participants’ reported critical incidents of toxic leader targeting to conceptualize and to narrate the relationship between toxic targeting and voluntary employee turnover. The study found evidence to support a direct link between toxic targeting and voluntary employee turnover and reports the categories of leader characteristics study participants’ identified as toxic. -

Gaslighting, Misogyny, and Psychological Oppression Cynthia A

The Monist, 2019, 102, 221–235 doi: 10.1093/monist/onz007 Article Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/monist/article-abstract/102/2/221/5374582 by University of Utah user on 11 March 2019 Gaslighting, Misogyny, and Psychological Oppression Cynthia A. Stark* ABSTRACT This paper develops a notion of manipulative gaslighting, which is designed to capture something not captured by epistemic gaslighting, namely the intent to undermine women by denying their testimony about harms done to them by men. Manipulative gaslighting, I propose, consists in getting someone to doubt her testimony by challeng- ing its credibility using two tactics: “sidestepping” (dodging evidence that supports her testimony) and “displacing” (attributing to her cognitive or characterological defects). I explain how manipulative gaslighting is distinct from (mere) reasonable disagree- ment, with which it is sometimes confused. I also argue for three further claims: that manipulative gaslighting is a method of enacting misogyny, that it is often a collective phenomenon, and, as collective, qualifies as a mode of psychological oppression. The term “gaslighting” has recently entered the philosophical lexicon. The literature on gaslighting has two strands. In one, gaslighting is characterized as a form of testi- monial injustice. As such, it is a distinctively epistemic injustice that wrongs persons primarily as knowers.1 Gaslighting occurs when someone denies, on the basis of another’s social identity, her testimony about a harm or wrong done to her.2 In the other strand, gaslighting is described as a form of wrongful manipulation and, indeed, a form of emotional abuse. This use follows the use of “gaslighting” in therapeutic practice.3 On this account, the aim of gaslighting is to get another to see her own plausible perceptions, beliefs, or memories as groundless.4 In what follows, I develop a notion of manipulative gaslighting, which I believe is necessary to capture a social phenomenon not accounted for by epistemic gaslight- ing. -

V. 2.1 Gaslighting Citizens Eric Beerbohm and Ryan Davis1

v. 2.1 Gaslighting Citizens Eric Beerbohm and Ryan Davis1 [L]eaders...have argued that if their followers or subjects are not strong enough to stick to the resolution themselves, they—the leaders—ought to help them avoid contact with the misleading evidence. For this reason, they have urged or compelled people not to read certain books, writings, and the like. But many people need no compulsion. They avoid reading things, and so on. — Saul Kripke, “On Two Paradoxes of Knowledge” Politics invariably involves disagreement—some of it, unreasonable. If deep enough and fundamental enough, disagreement might be taken as a sign not only that one of the opposing disputants must be incorrect, but that someone may be somehow failing to respond to the available evidence in a minimally rational way. So begins a much sharper allegation: that one’s opponent is not just mistaken, but crazy. In a partisan world, the rhetorical force of this accusation is easily weaponized. If one’s opponents lack basic epistemic capacities, one does them no wrong by ignoring them, and encouraging others to ignore them as well. “Gaslighting”—or attempting to cause people to doubt their own attitudes or capacities—has quickly gained popularity as an explicitly political charge.2 Antagonists on the right and left both mutually accuse each other of gaslighting. They define the term similarly, so the disagreement looks substantive.3 But the opposing outlooks may share little besides the concept. This essay aims to understand gaslighting as a political phenomenon. It proceeds in six parts. First, we will sketch the concept of gaslighting as it has been developed in the philosophical literature. -

The Sociology of Gaslighting

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122419874843American Sociological ReviewSweet 874843research-article2019 American Sociological Review 2019, Vol. 84(5) 851 –875 The Sociology of Gaslighting © American Sociological Association 2019 https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419874843DOI: 10.1177/0003122419874843 journals.sagepub.com/home/asr Paige L. Sweeta Abstract Gaslighting—a type of psychological abuse aimed at making victims seem or feel “crazy,” creating a “surreal” interpersonal environment—has captured public attention. Despite the popularity of the term, sociologists have ignored gaslighting, leaving it to be theorized by psychologists. However, this article argues that gaslighting is primarily a sociological rather than a psychological phenomenon. Gaslighting should be understood as rooted in social inequalities, including gender, and executed in power-laden intimate relationships. The theory developed here argues that gaslighting is consequential when perpetrators mobilize gender- based stereotypes and structural and institutional inequalities against victims to manipulate their realities. Using domestic violence as a strategic case study to identify the mechanisms via which gaslighting operates, I reveal how abusers mobilize gendered stereotypes; structural vulnerabilities related to race, nationality, and sexuality; and institutional inequalities against victims to erode their realities. These tactics are gendered in that they rely on the association of femininity with irrationality. Gaslighting offers an opportunity for sociologists to theorize under-recognized, -

Bullying in the Workplace Procedures Already Done; Input

Texas Board of Nursing Bulletin A Quarterly Publication of the Texas Board of Nursing The mission of the Texas Board of Nursing is to protect and promote the welfare of the people of Texas by ensuring that each person holding a license as a nurse in the State of Texas is competent to practice safely. The Board fulfills its mission through the regulation of the practice of nursing and the approval of nursing education programs. This mission, derived from the Nursing Practice Act, January 2016 supersedes the interest of any individual, the nursing profession, or any special interest group. Texas Nurses Selected Texas Board of Nursing to Undergo Review by the to Pilot Choosing Texas Sunset Advisory Commission Wisely® Campaign The Texas Board of Nursing (BON) will Texas Sunset Advisory Commission Nursing is consistently rated as the undergo review by the Texas Sunset website at: https://www.sunset.texas. most trusted profession and nurses Advisory Commission during the 2016- gov/ . The Commission meets following 2017 review cycle for the 85th Legislative the public hearing to consider and vote are one of the largest providers of Session. The Texas Sunset Advisory on which changes will be recommended patient care. For that reason, it is im- Commission was established by the to the full Texas Legislature during the perative that nursing practice be evi- Texas Legislature following passage of 85th Legislative Session. dence-based. The Choosing Wisely® the Texas Sunset Act in 1977. The Sunset campaign has an identified goal of Advisory Commission performs periodic The third and final phase of the Sunset facilitating wise decision making assessments of state agencies to answer review process entails legislative action. -

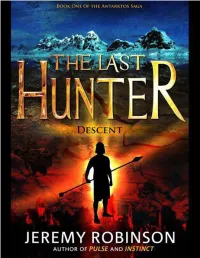

THE LAST HUNTER by Jeremy Robinson

THE LAST HUNTER By Jeremy Robinson OTHER NOVELS by JEREMY ROBINSON Threshold (coming in 2011) Instinct Pulse Kronos Antarktos Rising Beneath Raising the Past The Didymus Contingency PRAISE FOR WORKS OF JEREMY ROBINSON Skip front-matter to table of contents "Rocket-boosted action, brilliant speculation, and the recreation of a horror out of the mythologic past, all seamlessly blend into a rollercoaster ride of suspense and adventure." -- James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of JAKE RANSOM AND THE SKULL KING'S SHADOW "With THRESHOLD Jeremy Robinson goes pedal to the metal into very dark territory. Fast-paced, action- packed and wonderfully creepy! Highly recommended!" --Jonathan Maberry, NY Times bestselling author of ROT & RUIN "Jeremy Robinson is the next James Rollins" -- Chris Kuzneski, NY Times bestselling author of THE SECRET CROWN "If you like thrillers original, unpredictable and chock-full of action, you are going to love Jeremy Robinson..."- - Stephen Coonts, NY Times bestselling author of DEEP BLACK: ARCTIC GOLD "How do you find an original story idea in the crowded action-thriller genre? Two words: Jeremy Robinson." -- Scott Sigler, NY Times Bestselling author of ANCESTOR "There's nothing timid about Robinson as he drops his readers off the cliff without a parachute and somehow manages to catch us an inch or two from doom." -- Jeff Long, New York Times bestselling author of THE DESCENT "Greek myth and biotechnology collide in Robinson's first in a new thriller series to feature the Chess Team... Robinson will have readers turning the pages..." -- Publisher's Weekly "Jeremy Robinson’s THRESHOLD is one hell of a thriller, wildly imaginative and diabolical, which combines ancient legends and modern science into a non-stop action ride that will keep you turning the pages until the wee hours.