BUILDING MEMORY on the Symbolic Function of Contemporary Memorial Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highlights of What We Will Be Doing in NYC

“Learning by Experience” LEGACIES OF NEW YORK: The MUNDO Fall Break Experience 2019 Highlights of what we will be doing in NYC John's of Times Square has been voted one of New York's best pizzas because of its unique characteristics. All pizzas are made to order in one of our four coal-fired brick ovens and like a cast iron pan, our ovens season with age, making no two pizzas the same. The 800 degree coal fired ovens have no thermostats to control heat and are operated by our pizza men who have gone through months of extensive training. We pride ourselves on our fresh ingredients and incomparable recipes, making our pizzas second to none. The National September 11 Memorial & Museum (also known as the 9/11 Memorial & Museum) is a memorial and museum in New York City commemorating the September 11, 2001 attacks, which killed 2,977 people, and the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, which killed six.[4] The memorial is located at the World Trade Center site, the former location of the Twin Towers that were destroyed during the September 11 attacks. It is operated by a non-profit institution whose mission is to raise funds for, program, and operate the memorial and museum at the World Trade Center site. A memorial was planned in the immediate aftermath of the attacks and destruction of the World Trade Center for the victims and those involved in rescue and recovery operations.[5] The winner of the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition was Israeli-American architect Michael Arad of Handel Architects, a New York- and San Francisco-based firm. -

Newsletter of Architecture E Summer/Fallc2004h R I 5 C a T6 7

www.coa.gatech.edu Collegenewsletter of Architecture e summer/fallc2004h r i 5 c a t6 7 ARCHITECTURE ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY/MUSIC BUILDING CONSTRUCTION CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING CONTINUING EDUCATION INDUSTRIAL DESIGN PH.D. PROGRAM 8 9 QQE 10 Q E q e Letter from the Dean World Trade Center Memorial Competition, Clearly, international immersion of our stu- while another, Hawa Meskinyar, from dents is regarded as an important goal for Afghanistan returned to her home country both the Institute and the College, but why? and founded a humanitarian organization First, this experience is absolutely critical to e committed to helping women and children in the diversity of knowledge we desire for our Afghanistan find their way toward independ- students. This emphasis also has very practical ence. Other of our graduates, such as Mona importance due to the globalization of design, As can be seen in several stories of this El-Mousfy and Samia Rab are on the faculty construction and planning practice and the newsletter issue, the international thrusts of in the School of Architecture and Design at need for our graduates to be competitive in the College are clearlyu evident, involving stu- the American University of Sharjah in the this practice. But it is also important for dents, faculty and alumni. Recent interna- UAE, and another, Mohamed Bechir Kenzari, Georgia Tech and other major research uni- tional engagements of our faculty and stu- is winnere of the 2003 Outstanding Article of versities to continue its long-standing practice dents are quite diverse: the Year from the Association of Collegiate of educating future leaders and professional c• Ecuador –t the work of Professors Ellen Schools of Architecture and is on the faculty experts in the built environment in countries Dunham-Jones, Michael Gamble and Randy of the School of Architectural Engineering at throughout the world. -

Institutional Backgrounder

INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUNDER This document serves as an informational tool for members of the media who are interested in the National September 11 Memorial & Museum. Those looking for access to the Memorial and Museum are encouraged to visit the online media center. Please direct specific media inquiries to [email protected]. ESSENTIAL MEDIA BRIEFING • There are 2,983 names on the 9/11 Memorial, honoring the 2,977 people killed at the three attack sites on September 11, 2001 and the six people killed in the February 26, 1993 bombing at the World Trade Center. • The 9/11 attacks killed 2,977 people. 2,753 people were killed in New York, 184 people were killed at the Pentagon and 40 people were killed on Flight 93. • The February 26, 1993 bombing killed 6 people at the World Trade Center. • The largest loss of life of rescue personnel in American history occurred on September 11, 2001. 343 FDNY firefighters, along with 37 Port Authority Police Department officers and 23 New York Police Department officers, were killed. In total, 441 first responders representing over 30 agencies died on 9/11. • The Memorial pools stand in the footprints of the Twin Towers. Each pool is one acre in size. There are 413 swamp white oak trees on the Memorial plaza, and one callery pear tree known as the Survivor Tree. • The 9/11 Memorial Glade is located in the southwest corner of the Memorial. The Glade is dedicated to all who are sick or have died as a result of exposure to toxins and hazards in the aftermath of 9/11 as well as those who responded with courage and bravery. -

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project Lynne B. Sagalyn THREE YEARS after the terrorist attack of September 11,2001, plans for four key elements in rebuilding the World Trade Center (WC) site had been adopted: restoring the historic streetscape, creating a new public transportation gate- way, building an iconic skyscraper, and fashioning the 9/11 memorial. Despite this progress, however, what ultimately emerges from this heavily argued deci- sionmakmg process will depend on numerous design decisions, financial calls, and technical executions of conceptual plans-or indeed, the rebuilding plan may be redefined without regard to plans adopted through 2004. These imple- mentation decisions will determine whether new cultural attractions revitalize lower Manhattan and whether costly new transportation investments link it more directly with Long Island's commuters. These decisions will determine whether planned open spaces come about, and market forces will determine how many office towers rise on the site. In other words, a vision has been stated, but it will take at least a decade to weave its fabric. It has been a formidable challenge for a city known for its intense and frac- tious development politics to get this far. This chapter reviews the emotionally charged planning for the redevelopment of the WTC site between September 2001 and the end of 2004. Though we do not yet know how these plans will be reahzed, we can nonetheless examine how the initial plans emerged-or were extracted-from competing ambitions, contentious turf battles, intense architectural fights, and seemingly unresolvable design conflicts. World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project 25 24 Contentious City ( rebuilding the site. -

9/11 Memorial

MAKING THE 9/11 MEMORIAL EDUcatOR’S GUIDE Memorial at Night. Visualization by Squared Design Lab KEY TERMS: In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, Americans from all walks of life joined together to rebuild the area around the World Trade Center. Students may want to define the list The nation grieved the loss of nearly 3,000 Americans as the result of terms below which are referenced of these horrific attacks in New York City. As time passed, a huge in this program, and they can also decision loomed at the site: what was the best way to memorialize keep their own list of terms to define and pay tribute to those who lost their lives? This 1-hour HISTORY® as they watch. special is a behind-the-scenes exploration of the process of con- structing the 9/11 Memorial, from its inception through its installation. Arduous An architect named Michael Arad was the winner of a worldwide Bevel competition to design a memorial for the site. Arad’s design, entitled Commemorate “Reflected Absence” is situated on 8 acres of land near the Twin Fabrication Towers site, with two waterfalls cascading into reflecting pools below Parapet the surface of the ground. Bronze parapets at the site are inscribed Patina with the names of those who lost their lives on 9/11 and in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. This program gives students an oppor- Prevail tunity to reflect on the significance of 9/11 through the eyes of those Tangible who conceptualized and created this meaningful memorial. -

On May 17, 2006, Governor George E. Pataki and Mayor Michael R

FRANK J. SCIAME WORLD TRADE CENTER MEMORIAL DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS AND ANALYSIS INTRODUCTION On May 17, 2006, Governor George E. Pataki and Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg announced that we would help lead the effort to ensure a buildable World Trade Center Memorial. The goal of our process was to ensure the World Trade Center Memorial be brought in line with the $500 million budget while remaining consistent with the Reflecting Absence vision and Daniel Libeskind’s Master Plan for the World Trade Center site. This document summarizes the findings and recommendations that arose from our process. After several phases of value engineering and analysis of the various components of the Memorial, Memorial Museum, and Visitor Orientation and Education Center (VOEC) design, we narrowed the field of options and revisions that were most promising to fulfill the vision of the Reflecting Absence design and the Master Plan, while providing significant cost savings and meeting the schedule to open the Memorial on September 11, 2009. Various potential design refinements were reviewed at a meeting with the Governor and the Mayor on June 15, 2006. Upon consultation with the Governor and the Mayor, it was determined that one option best fulfilled the three guiding principles articulated below. BACKGROUND SELECTION OF WTC SITE MASTER PLAN (Following are excerpts on the LMDC’s process – for more information please visit: http://www.renewnyc.com/plan_des_dev/wtc_site/Sept2003Overview.asp) In the summer of 2002, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) initiated a worldwide search for design and planning professionals to propose a visionary land use plan for the World Trade Center area. -

NEW YORK CITY and 9/11 MEMORIAL COMMEMORATE 12Th ANNIVERSARY of SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 11, 2013 NEW YORK CITY AND 9/11 MEMORIAL COMMEMORATE 12th ANNIVERSARY OF SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 (New York) September 11, 2013 – The National September 11 Memorial & Museum today observed the 12th anniversary of September 11 by remembering and honoring the 2,983 men, women and children killed in the attacks at the World Trade Center site, the Pentagon, aboard Flight 93, and those who died in the February 26, 1993 WTC bombing. The ceremony at the 9/11 Memorial was for victims’ family members, who participated in the reading of the 2,983 names. There were six moments of silence, marking the times the planes struck the Twin Towers, when each tower collapsed, the attack on the Pentagon and the crash of Flight 93 near Shanksville, Pa. The first moment of silence was at 8:46 a.m. “Today, we come together to remember and honor the thousands of innocent men, women and children who were taken from us too soon 12 years ago. We also recognize the endurance of those who survived, the courage of those who risked their lives to save others, and the compassion of all who supported us along the path of recovery,” 9/11 Memorial President Joe Daniels said. “In the wake of the attacks, we showed the world that the best of humanity can overcome the worst hate.” The 9/11 Memorial has welcomed nearly 10 million visitors from all 50 states and 188 nations since opening in the fall of 2011. Construction on the accompanying 9/11 Memorial Museum continues to move forward in anticipation of its opening in the spring of 2014. -

The Park 51/Ground Zero Controversy and Sacred Sites As Contested Space

Religions 2011, 2, 297-311; doi:10.3390/rel2030297 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article The Park 51/Ground Zero Controversy and Sacred Sites as Contested Space Jeanne Halgren Kilde University of Minnesota, 245 Nicholson Hall, 216 Pillsbury Dr. SE., Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: 612-625-6393 Received: 9 June 2011; in revised form: 14 July 2011 / Accepted: 19 July 2011 / Published: 25 July 2011 Abstract: The Park 51 controversy swept like wildfire through the media in late August of 2010, fueled by Islamophobes who oppose all advance of Islam in America. Yet the controversy also resonated with many who were clearly not caught up in the fear of Islam. This article attempts to understand the broader concern that the Park 51 project would somehow violate the Ground Zero site, and, thus, as a sign of "respect" should be moved to a different location, an argument that was invariably articulated in “spatial language” as groups debated the physical and spatial presence of the buildings in question, their relative proximity, and even the shadows they cast. This article focuses on three sets of spatial meanings that undergirded these arguments: the site as sacred ground created through trauma, rebuilding as retaliation for the attack, and the assertion of American civil religion. The article locates these meanings within a broader civic discussion of liberty and concludes that the spatialization of the controversy opened up discursive space for repressive, anti-democratic views to sway even those who believe in religious liberty, thus evidencing a deep ambivalence regarding the legitimate civic membership of Muslim Americans. -

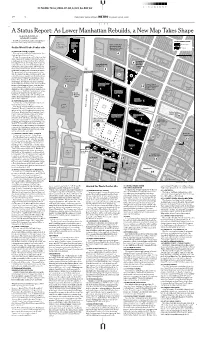

As Lower Manhattan Rebuilds, a New Map Takes Shape

ID NAME: Nxxx,2004-07-04,A,024,Bs-BW,E2 3 7 15 25 50 75 85 93 97 24 Ø N THE NEW YORK TIMES METRO SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2004 CITY A Status Report: As Lower Manhattan Rebuilds, a New Map Takes Shape By DAVID W. DUNLAP and GLENN COLLINS Below are projects in and around ground DEVELOPMENT PLAN zero and where they stood as of Friday. Embassy Goldman Suites Hotel/ Sachs Bank of New York BUILDINGS UA Battery Park Building Technology and On the World Trade Center site City theater site 125 Operations Center PARKS GREENWICH ST. 75 Park Place Barclay St. 101 Barclay St. (A) FREEDOM TOWER / TOWER 1 2 MURRAY ST. Former site of 6 World Trade Center, the 6 United States Custom House 0Feet 200 Today, the cornerstone will be laid for this WEST BROADWAY skyscraper, with about 60,000 square feet of retail space at its base, followed by 2.6 mil- Fiterman Hall, lion square feet of office space on 70 stories, 9 Borough of topped by three stories including an obser- Verizon Building Manhattan PARK PL. vation deck and restaurants. Above the en- 4 World 140 West St. Community College closed portion will be an open-air structure Financial 3 5 with wind turbines and television antennas. Center 7 World The governor’s office is a prospective ten- VESEY ST. BRIDGE Trade Center 100 Church St. ant. Occupancy is expected in late 2008. The WASHINGTON ST. 7 cost of the tower, apart from the infrastruc- 3 World 8 BARCLAY ST. ture below, is estimated at $1 billion to $1.3 Financial Center billion. -

David Azrieli Architecture Student Prize Winners

Greetings from Danna Azrieli, Chairman — Azrieli Foundation Israel Dear Students, Graduates, Faculty, Architects and Architecture Enthusiasts, The David Azrieli Architecture Student Prize meets Israel’s young architects at an important milestone in their professional lives, when theory and practice converge. The Prize appraises and rewards students for their final project and their dream of making a personal imprint on the public space, the environment, society and public discourse. Over the years, the Prize has become an integral part of architecture education in Israel, with the heads of the five schools of architecture valuing it as a certificate of excellence. The final projects that made the short list are the best among the student works, and embody the extensive knowledge acquired by them during their years of study. As in previous years, this year Azrieli Foundation Canada — Israel presents generous grants to the three finalists — a first prize of 60,000 shekels, a second prize of 25,000 shekels, and a third prize of 10,000 shekels. On behalf of the Foundation, I send my thanks to this year’s panel of judges, headed by the esteemed architect Bracha Chyutin; my sister, Dr. Sharon Azrieli; architect Michael Arad; architect Yoav Meiri; and architect Gil Shenhav. DAVID AZRIELI ARCHITECTURE STUDENT PRIZE I would also like to extend a special thank you to Professor Carmela Jacoby-Volk, who advised us professionally on the competition process. The David Azrieli Prize honors and congratulates not only the winners, but all the students who submitted projects and contended for a place in the competition. I hope that this tradition will continue to inspire architecture students PAGE and the architecture community for many years to come. -

Community Impact on Post 9/11 Urban Planning of Lower

COMMUNITY IMPACT ON POST 9/11 URBAN PLANNING OF LOWER MANHATwin TowersAN: FORM FOLLOWS VALUES by LAURA JANINE HOFFMAN (Under the Direction of HANK METHVIN) ABSTRACT Community response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 on the World Trade Center Twin Towers was immediate, and had indelible impact on subsequent urban planning in Lower Manhattan. Community and civic groups formed to do grassroots research and design in an inclusive and transparent process. Individuals’ hopes for the rebuilding of their city were collected through citywide workshops, town meetings, public forums, and websites. The resulting vision is a comprehensive and integrated view of urban infrastructure and human needs. It is a reflection of current cultural values, and necessitated a change in the guiding principles for rebuilding Lower Manhattan. The clarity and consistency of the community’s themes is uncanny, and was foreshadowed by post-modern urbanists: 1.Remembrance / memorial 2. Human capital/ jobs, job training, education 3. Affordable housing 4.Hubs and sub centers with links 5. Design Excellence 6. Sustainable: buildings, pedestrian friendly, transportation 7. mass transit improvements 8. Community = 24/7; connect neighborhoods; use waterfront and open spaces 9. Cultural diversity; institutions and incubator spaces INDEX WORDS: World Trade Center, Twin Towers, Manhattan, Lower Manhattan, September 11, 2001, 911, 9/11, community, values, principles, urban planning, post-modern urbanism, sustainable, 24/7, mixed use, pedestrian-friendly, cultural -

Reflecting Absence

Peer Reviewed Title: Reflecting Absence Journal Issue: Places, 21(1) Author: Arad, Michael Publication Date: 2009 Publication Info: Places Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/5nf4t3k6 Acknowledgements: This article was originally produced in Places Journal. To subscribe, visit www.places-journal.org. For reprint information, contact [email protected]. Keywords: places, placemaking, architecture, environment, landscape, urban design, public realm, planning, design, volume 21, issue 1, Recovering, michael, arad, reflecting, absence Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Reflecting Absence Michael Arad We begin the second half of this theme section with a narrative altered; changes have been made to the program; and the by Michael Arad concerning his winning design for the World boundaries of the memorial itself have been renegotiated as a Trade Center Memorial. Our intent is to provide a record, a result of the complex process of recovering the WTC site. memory, of the origins of this project. But in Arad’s own words we are offered a rare glimpse of The notion of “project” certainly applies here. From its the designer’s original concept. The story presents a fascinat- inception, this memorial was intended to serve as an object ing record of how a complex process began—how a design of multiple cultural, emotional, and societal valences, which vision was born, and how it germinated in personal reflec- would exist in our present as well as in the “here and now” tions about the meaning of tragedy and the requirements for of many, unimaginable, futures.