Imlah 2008 03Novel.Pdf (481.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Im Auftrag: Medienagentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected]

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] The Kinks At The BBC (Box – lim. Import) VÖ: 14. August 2012 CD1 10. I'm A Lover, Not A Fighter - Saturday Club - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 1. Interview: Meet The Kinks ' Saturday Club 11. Interview: Ray Talks About The USA ' -The Playhouse Theatre, 1964 Saturday Club - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 2. Cadillac ' Saturday Club - The Playhouse 12. I've Got That Feeling ' Saturday Club - Theatre, 1964 Piccadilly Studios, 1964 3. Interview: Ray Talks About 'You Really Got 13. All Day And All Of The Night ' Saturday Club Me' ' Saturday Club The Playhouse Theatre, - Piccadilly Studios, 1964 1964 14. You Shouldn't Be Sad ' Saturday Club - 4. You Really Got Me ' Saturday Club - The Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, September 1964 15. Interview: Ray Talks About Records ' 5. Little Queenie ' Saturday Club - The Saturday Club - Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 16. Tired Of Waiting For You - Saturday Club - 6. I'm A Lover Not A Fighter ' Top Gear - The Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 17. Everybody's Gonna Be Happy ' Saturday 7. Interview: The Shaggy Set ' Top Gear - The Club -Maida Vale Studios, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 18. This Strange Effect ' 'You Really Got.' - 8. You Really Got Me ' Top Gear - The Aeolian Hall, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, October 1964 19. Interview: Ray Talks About "See My Friends" 9. All Day And All Of The Night ' Top Gear - The ' 'You Really Got.' Aeolian Hall, 1965 Playhouse Theatre, 1964 20. See My Friends ' 'You Really Got.' Aeolian Hall, 1965 1969 21. -

What I Learned in Pittsburgh Forestalling Ecocide with the Age of Stupid

North of CeNter Wednesday, OctOber 7, 2009 Free take home and read VOluMe I, Issue 11 Faust summoned What I learned in Pittsburgh to set Lex ablaze The 2009 G20 summit and protests, part 1 Krautrockers play Boomslang By Trevor Tremaine In the mid 1990s, I was a subur- ban teenager entering a lifelong obses- sion with strange, adventurous music. before Myspace, peer-to-peer fileshar- ing, Mutant sounds and other blogs of its ilk , and without regular access to many interesting all-ages gigs or the sorts of fantastic record stores that were found in louisville or cincinnati (each requiring an hour-plus drive), discovering such sounds was a rather labor-intensive process. Often, I would just peruse the CDs in (the legendary, long-gone lexington record store) cut corner’s scant, rarely- restocked avant-garde section and select a disc based solely on the cover art, the description, or the instrumen- tation, if the credits were visible (i.e. if personnel were attributed with “tapes and electronics,” I knew I had to check it out—an axiom that still holds true today). For guidance, I sought The Wire magazine, a UK journal of experimen- tal music from around the world. One memorable issue listed “100 records that set the World on Fire (While no One Was listening),” and I made it my MICHAEL MARCHMAN mission to hear as many of these very, Crowds of protestors gather in downtown Pittsburgh during the recent G20 meetings. very obscure records as I could find. Faust was a name that popped up By Michael Dean Benton gesture of political optimism. -

Dec 2020 Nuts Bolts V5 Issue 6

E! NUTS & BOLTS ‘Every man needs a shed’ Vol 5 | Issue 6 | December 2020 [Covid-19 Edition 7] In This Edition Page 2 Melbourne Cup BBQ Lunch Page 3 Bulimba Markets Page 4 Corrugated Shed Update Message from the Editor Page 5 Vetrans Grant Activities Editor: Ray Peddersen Page 6 Care Kits for Kids Qld visit [email protected] Page 7 Contract Bridge Corner Page 8 N&B Archive Page 9 Poetry Corner - Lest We Forget Page 10 Shoulder to Shoulder This is the last “Nuts& Bolts” for 2020, so please enjoy. Page 11 Time in Uniform Page 13 Great Moments in Science As this crazy year of covid draws to a close, I would like to Page 14 Puzzles, Jokes & Trivia thank all those members who have contributed poems travel photos, jokes and articles for Nuts & Bolts and I wish every member of the shed and their families a very Happy and Safe Christmas. Mens Shed Carina Inc., Clem Jones Centre Ph: 07 3395 0678 56 Zahel Street E: [email protected] CARINA, QLD, 4152 W: www.carinamensshed.org.au Carina Men’s Shed valued supporters include: Amanda Van de Hoef 1 Nuts & Bolts Newsletter | Carina Men’s Shed Vol 5 | Issue 6 | December 2020 Member’s News Melbourne Cup Lunch Tuesday 03 November Small field of about 25 turned up for the Melbourne Cup lunch, Paul Gardiner did a great job on the BBQ lunch refreshments and thanks to Roger Appleby and John Abbott for organising the sweeps. 2 Nuts & Bolts Newsletter | Carina Men’s Shed Vol 5 | Issue 6 | December 2020 Member’s News Bulimba Markets Sunday 15 November Eddie Haselich, John Kirkwood, Freddie Butler, Rex Gelfius and David Sim set up our stall at the Bulimba Markets and had a very successful afternoon raising $1600 from the sale of our shed’s glass, wood and leather items. -

Download Ebook (PDF)

The Pilgrims Books by Chester Eagle Hail and Farewell! An evocation of Gippsland (non-fiction, 1971) Who could love the nightingale? (novel, 1974) Four faces, wobbly mirror (novel, 1976) At the window (novella, 1984) The garden gate (novel, 1984) Mapping the paddocks (non-fiction, 1985) Play together, dark blue twenty (non-fiction, 1986) House of trees (reissue of Hail and Farewell! 1987) Victoria Challis (novel, 1991) House of music (stories, 1996) Wainwrights’ mountain (novel, 1997) Waking into dream (novel, 1998) didgeridoo (stories, 1999) Janus (travel pieces, 2001) The Centre & other essays (essays, 2002) Love in the Age of Wings & other operas (librettos, 2003) Melba: an Australian city (essays, 2004) The Wainwright Operas (librettos, 2005) Oztralia (essays, 2005) Cloud of knowing (novel, 2006) Benedictus (essays, 2006) Central Station Sydney & other operas (librettos, 2006) The Sun King & other operas (librettos, 2007) The Well in the Shadow (literary essays, 2008) All the Way to Z (memoir/essay, 2009) This Enchanted World & other operas (librettos, 2009) Running The Race (novel, 2010) A Mob Of Galahs & other operas (librettos, 2011) Brighter Than Black (libretto, 2012) The Pilgrims (novel, 2012) (See also mini-mags over the next page.) If you would like to know more about the books listed above or to download any of them for yourself, FREE OF CHARGE, visit trojanpress.com.au. The Pilgrims Chester Eagle The Pilgrims is published by Chester Eagle, 23 Langs Road Ivanhoe 3079 Australia, operating as Trojan Press. Phone is 61 3 9497 1018 and email address is [email protected] Copyright is held by Chester Eagle. -

CHARTED TERRITORY by NETA GORDON Thesis Submitted to The

CHARTED TERRITORY Women Nriting Genealogy in Recent Canadian Fiction by NETA GORDON Thesis submitted to the Department of English In conformity with the requirements fx The degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen's University Kingston. Ontario. Canada November. 200 1 Copyright O Neta Gordon 2001 uisiaans and Acquisitions et 3-Bi mgogrPphic Services seMees WliraphQues The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclwive licence aiiowing the exclusive permettant à la National Li- of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownetshtp of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette dièse. thesis nor substantial extracts fbmit Ni la thése ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This dissertation argues that the recent refashioning of the genealogical plot by Canadian women entails a dual process whereby, on the one hand, the idea of family is radically redefined and, on the other hand, the conservative traditions of family are in some way recuperated. For my analysis of the multi-generational family history, 1 develop a complex critical framework which demonstrates that the organizing principles goveming any particular conception of family will also influence the way that family's story is nmted. -

Wishing All Readers a Very Happy South Dock Festival and Summer Activities

ISSUE 67 SUMMER 2005 Members of St. Andrew ’ s Rostrevor / Charlemont Street made their yearly pilgrimage to Wex f o r d. This being the 2nd year. A lot of local trips took place, such as Vinegar Hill (pictured above), Hook Head, Wat e rf o r d Shopping trip, also a lot of activities took place in the Ferryc a r rig Hotel, for instance; Bingo each night, Singalongs, various music nights. The atmosphere between everybody was so heartening and friendly. The 5 days and nights flew by so qu i c k l y . A special thank you to Pearse Street Gardai, Inspector Eamonn Murphy, Sergeant John Shovlan, Declan O’Rourke, Betty Watson, Betty Ashe, Alice Bregazzi, Mrs. Carmo d y , sponsors and all the volunteers for their hard work and dedication. On behalf of their communities this very unique trip will take place next year and long may it continue!! See Picture Special on page 23. (By Paddy McGauley) Wishing all Readers a very Happy South Dock Festival and Summer Activities EDITOR: PATRICK McGAULEY PHOTOS: PADDY GIBSON, NOEL WATSON SECRETARY: ANN MAHER THE NEW LINK, ST. ANDREWS RESOURCE CENTRE, 114-116 PEARSE STREET. Telephone: 677 1930. Fax: 671 5734 The New Link is published by St. Andrews Resource Centre. Extract from the magazine may be quoted or published on condition that acknowledgement is given to the New Link. Views expressed in this magazine are the contributors’ own and do not reflect the views of St. Andrews Resource Centre. ARTICLES: The New Link Magazine would like to hear your news and views. -

RCA Consolidated Series, Continued

RCA Discography Part 18 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Consolidated Series, Continued 2500 RCA Red Seal ARL 1 2501 – The Romantic Flute Volume 2 – Jean-Pierre Rampal [1977] (Doppler) Concerto In D Minor For 2 Flutes And Orchestra (With Andraìs Adorjaìn, Flute)/(Romberg) Concerto For Flute And Orchestra, Op. 17 2502 CPL 1 2503 – Chet Atkins Volume 1, A Legendary Performer – Chet Atkins [1977] Ain’tcha Tired of Makin’ Me Blue/I’ve Been Working on the Guitar/Barber Shop Rag/Chinatown, My Chinatown/Oh! By Jingo! Oh! By Gee!/Tiger Rag//Jitterbug Waltz/A Little Bit of Blues/How’s the World Treating You/Medley: In the Pines, Wildwood Flower, On Top of Old Smokey/Michelle/Chet’s Tune APL 1 2504 – A Legendary Performer – Jimmie Rodgers [1977] Sleep Baby Sleep/Blue Yodel #1 ("T" For Texas)/In The Jailhouse Now #2/Ben Dewberry's Final Run/You And My Old Guitar/Whippin' That Old T.B./T.B. Blues/Mule Skinner Blues (Blue Yodel #8)/Old Love Letters (Bring Memories Of You)/Home Call 2505-2509 (no information) APL 1 2510 – No Place to Fall – Steve Young [1978] No Place To Fall/Montgomery In The Rain/Dreamer/Always Loving You/Drift Away/Seven Bridges Road/I Closed My Heart's Door/Don't Think Twice, It's All Right/I Can't Sleep/I've Got The Same Old Blues 2511-2514 (no information) Grunt DXL 1 2515 – Earth – Jefferson Starship [1978] Love Too Good/Count On Me/Take Your Time/Crazy Feelin'/Crazy Feeling/Skateboard/Fire/Show Yourself/Runaway/All Nite Long/All Night Long APL 1 2516 – East Bound and Down – Jerry -

“Think of Me As Your Conscience”: Spectres in Recent English-Canadian Historical Fiction

“Think of me as your conscience”: Spectres in recent English-Canadian historical fiction by Reginald G. D. Wiebe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Reginald G. D. Wiebe, 2015 ii “Think of me as your conscience”: Spectres in recent English-Canadian historical fiction Abstract In this dissertation I will discuss how English-Canadian writers of recent historical fiction incorporate ghosts for the purposes of recuperation: to suggest both the persistence of historical injustices and to signal the possibility of healing. Recognizing that views of Canada’s alleged ghostlessness perpetuate a colonial overwriting of the varied histories that preceded Confederation, many writers prominently feature history and hauntings to represent that Canada does, in fact, have a storied past. Recent historical fiction by English-Canadian writers has frequently demonstrated less interest in postmodern practices and more interest considering the past as ontologically stable, though not completely accessible. This is often, I argue, in the service of a postcolonial project to revise history to acknowledge the injustices and traumas that colonial historiography has suppressed. Spectres can negotiate a desire for retaining skepticism of the inherent biases of historiography and the need to maintain some level of historical certainty in order to advocate for a particular cause. Using Jacques Derrida’s concept of Hauntology and close readings of five novels, I contend that spectres are essential in postcolonial projects of illuminating the past for the purposes of recuperation in recent historical fiction. The goal of many novels of haunting and history is not only to note historical wrongs – to highlight the sense of unease and illegitimacy that ghosts signal – but also to suggest possible avenues of recovery. -

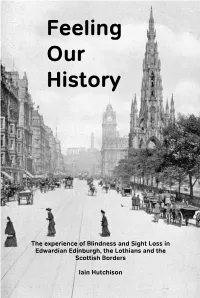

Feeling Our History

Feeling Our History The experience of Blindness and Sight Loss in Edwardian Edinburgh, the Lothians and the Scottish Borders Iain Hutchison Feeling Our History The experience of blindness and sight loss in Edwardian Edinburgh, the Lothians and the Scottish Borders Iain Hutchison Published in 2015 by RNIB Scotland 12-14 Hillside Crescent Edinburgh EH7 5EA Scotland Copyright © RNIB Scotland, 2015 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Feeling Our History: The experience of blindness and sight loss in Edwardian Edinburgh, the Lothians and the Scottish Borders A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-9934106-4-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission from the Publisher and copyright holder in writing. Typeset in Scotland by Delta Mac Artwork, [email protected] Printed in Scotland by J Mcvicar Printers, 97 Dykehead Street, Queenslie Industrial Estate, Glasgow G33 4AQ, Tel 0141 774 5132 Contents Acknowledgements . iii Forewords by John Legg, Sandra Wilson and Hazel McFarlane . vii Introduction . 1 Part 1 – Feeling Our History The Missions to the Outdoor Blind . 3 Edwardian Edinburgh. 9 The Register . 16 Charity and Philanthropy . 24 Poverty ................................................ 33 Employment – the able-bodied and disabled blind . 41 Education and Raised Type. 48 Religion . 57 Part 2 – Feeling Blind People’s Lives Agnes McArthur (1872-1956) . 64 Elizabeth (Lizzie) Ann Hoseason (1873-1914) . 67 Georgina McDonald (1871-1925) . 70 Isabella (Bella) Wood (1868-1964) . -

June 2014 Issue #6 June 2014 Issue #6 Chebeague Island Council Calendar

Photo by Cathy MacNeill June 2014 Issue #6 June 2014 Issue #6 Chebeague Island Council Calendar Contents: On the Cover: Chedemption 2 In the early 1900’s the Merriam-Horne Realty Co. built two cottages on the East End point property, hoping to attract people to buy lots and do likewise. The Graves Cottage on the April cover was one, and this was the other. It was sold to Alice Kelly Town of Chebeague 3 in 1908. She called it Olive Cottage and added a wrap around porch in 1909. She sold it in 1913 to Rev. Dr. Paterson-Smyth, an Episcopal Minister from Canada who held Graduates 4 church services in the living room. In 1924, Prof. Elijah Beach came to the island to visit Prof. Harmon, fell in love with and bought the cottage, changing the name to Beach Haven. His daughter, Nancy Beach Martindale, grew up here summers, so she Health Center 6 brought her family here to do so also. Now it is used by Fred & Donna Martindale as well as any and all of Ross Martindale’s and Fred’s children and grandchildren. Library 7 The monthly House Histories are selected and written by Martha Hamilton. Events 10 Upcoming events 11 About the Calendar Historical Society 12 Publisher: Chebeague Island Council Gin Ballard, President, 207-653-5651, [email protected] Editors: Tom and Elizabeth Schutte, [email protected] CICA 15 PO Box 12, Chebeague Island, ME 04017 Treasurer: Ariette Scott, 207-846-9324, [email protected] Recreation Center 16 Also available for comments/questions, Board members: Deb Bowman 846-0609, Donna Colbeth 846-3097, Louise Doughty 846-3128, Deb Hall 846-9034, Nancy Hill 846-4126, CTC 17 Mary Holman 846-1072, Ester Knight 846-4178, Mac Passano 846-7829, Gail Miller 846-4369, Carol Lynn Davis 846-8859, and Lola Armstrong 846-4737. -

In My Skin Pilot 17Th August 2018

IN MY SKIN PILOT 17TH AUGUST 2018 Written by Kayleigh Llewellyn C/o Expectation Entertainment 1 INT / EXT. BEDROOM OF A FANCY OCEAN VIEW APARTMENT - DAY 1 A FRENCH WOMAN’S SULTRY VOICE narrates over the below action. The sound of waves crashing in the distance, the occasional seagull caw. Almost like an art house French film... Almost. FRENCH WOMAN (V.O.) A seagull flew in and landed Gold shimmer on her wings * A seagull watches through open balcony doors as a BEAUTIFUL WOMAN, who will we come to know as POPPY, sleeps on white sheets, sunlight kissing her face. FRENCH WOMAN (V.O.) Bird in me, roaming freely My head weary * POPPY’S sipping coffee - froth on the end of her nose. She realises and laughs maniacally. FRENCH WOMAN (V.O.) My eyes teary This is love * POPPY jumps on the bed, jubilantly swinging a pillow in a pillow fight, but when the camera pans around - it’s the seagull stood there. As if it’s the bird she’s whacking... FRENCH WOMAN (V.O) Like a candle in a dark room Like a blow heater in a shed * POPPY’S lying on the bed, the sheets fluttering above her as she laughs. Just a seagull wing edging in to shot. FRENCH WOMAN (V.O) (CONT’D) But then Seagull flies away Even though you pray * The sun disappears, the saturation of the shot becoming cold and grey. The bed now empty. FRENCH WOMAN (V.O.) Gone for every day This is love * A spilt cup of coffee on the table, a single feather lying in the pooled liquid. -

Teaching Resource: Interview Methods

Teaching resource: Interview methods Illustrating interview methods using our extensive data collection Copyright © 2021 University of Essex. Created by UK Data Archive, UK Data Service Introduction Interviewing is a frequently used method in social research with its suitability being entirely dependent on the particular research question. Qualitative interviewing is generally distinguished from questionnaire-based interviewing, even if the form of communication, such as face-to face conversation, may be the same. This teaching resource provides instructors and students with materials designed to assist in teaching qualitative interviewing. The UK Data Service has created this resource to illustrate interview methods using its extensive data collection held as part of the UK Data Archive holdings, and, in particular, to assist instructors who have limited research materials of their own. The resource provides brief summaries of several different interviewing techniques and each summary is accompanied by full transcripts or excerpts and the interview schedule (or guidance notes). It concludes with selected references and practical suggestions for how to use the materials for teaching. Introduction to qualitative interviews Interviewing is a frequently used method in social research. It is generally distinguished from questionnaire-based interviewing, even if the form of communication, such as face-to face conversation, may be the same. Some interview styles produce highly structured data on people's opinions on a specific matter, whereas other interviews facilitate a more evocative communication of people's life experiences, activities, emotions and identities. Qualitative interviews In qualitative interviews the interviewees are given space to expand their answers and accounts of their experiences and feelings.