Recommending a New System: an Audience- Based Approach to Film Categorisation in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

06 MPLC US Producer List by Product

4/2/2019 LIB LIB The MPLC producer list is broken down into seven genres for your programming needs. Subject to the Umbrella License ® Terms and Conditions, Licensee may publicly perform copyrighted motion pictures and other audiovisual programs intended for personal use only, from the list of producers and distributors below in the following category: Public Libraries MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS Fox - Walden Fox 2000 Films Fox Look Fox Searchlight Pictures STX Entertainment Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. CHILDRENS Central Park Media Cosgrove Hall Films D'Ocon Family Entertainment Library Harvey Entertainment McGraw-Hill Peter Pan Video Scholastic Entertainment FAITH-BASED Alley Cat Films American Portrait Films Big Idea Entertainment Billy Graham Evangelistic Ass. / World British and Foreign Bible Society Candlelight Media Wide Pictures CDR Communications Choices, Inc. Christian Television Association Cross Wind Productions Crossroad Motion Pictures Crown Entertainment D Christiano Films DBM Films Elevation EO International ERF Christian Radio & Television Eric Velu Productions Gateway Films Gospel Films Grace Products/Evangelical Films Grizzly Adams Productions Harvest Productions International Christian Communications (ICC) International Films Jeremiah Films Kalon Media, Inc. Kingsway Communications Lantern Film and Video Linn Productions Mahoney Media Group, Inc. Maralee Dawn Ministries McDougal Films 4/2/2019 LIB LIB The MPLC producer list is broken down into seven genres for your programming needs. Subject to the -

Download-To-Own and Online Rental) and Then to Subscription Television And, Finally, a Screening on Broadcast Television

Exporting Canadian Feature Films in Global Markets TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS MARIA DE ROSA | MARILYN BURGESS COMMUNICATIONS MDR (A DIVISION OF NORIBCO INC.) APRIL 2017 PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF 1 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA), in partnership with the Association québécoise de la production médiatique (AQPM), the Cana- da Media Fund (CMF), and Telefilm Canada. The following report solely reflects the views of the authors. Findings, conclusions or recom- mendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders of this report, who are in no way bound by any recommendations con- tained herein. 2 EXPORTING CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS IN GLOBAL MARKETS Executive Summary Goals of the Study The goals of this study were three-fold: 1. To identify key trends in international sales of feature films generally and Canadian independent feature films specifically; 2. To provide intelligence on challenges and opportunities to increase foreign sales; 3. To identify policies, programs and initiatives to support foreign sales in other jurisdic- tions and make recommendations to ensure that Canadian initiatives are competitive. For the purpose of this study, Canadian film exports were defined as sales of rights. These included pre-sales, sold in advance of the completion of films and often used to finance pro- duction, and sales of rights to completed feature films. In other jurisdictions foreign sales are being measured in a number of ways, including the number of box office admissions, box of- fice revenues, and sales of rights. -

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

Complete Credits

Jerome Leroy CREDITS Awards Golden Lotus Awards / Vietnam Best Composer “The Housemaid: Cô Hàu Gái” Film Festival (2017) Hollywood Intl. Independent Best Score “Qi – The Documentary” Documentary Awards (2017) Jerry Goldsmith Awards (2017) Best Music: Short Film “Charlie’s Supersonic Glider” (nomination) Maverick Movie Awards (2016) Best Music: Feature “A Better Place” (nomination) Lyon Intnl. Film Festival (2016) Best Music (nomination) “A Better Place” Feature Films Killers Within Two Joker Films Paul Bushe & Brian O’Neill, dir. The Housemaid: Cô Hàu Gái HK Films Timothy Bui, prod.; Derek Nguyen, dir. A Better Place Digital Jungle Pictures Dennis Ho, prod. & dir. The Throwaways The Combine Jeremy Renner, Don Handfield, Timothy Bui, prod.; Tony Bui, dir. After Ever After AEA Rakesh Kumar, prod. & dir. #iKllr Kaleidoscope Film Distribution Jeffrey Coghlan, prod. & dir. The Mistover Tale Mistover Harry Tappan Heher, prod. & dir. A Very Harold & Kumar 3D Mandate Pictures / Greg Shapiro, prod., Todd Christmas New Line Cinema Strauss-Schulson, dir. (additional composer) Jerome Leroy • [email protected] • (310) 804-7210 • Page 1! The Hunger Games Lionsgate Nina Jacobson, Jon Kilik, prods.; (additional music programming) Gary Ross, dir. The Tale of Despereaux Universal Pictures Gary Ross, prod.; Sam Fell, Rob (music programming) Stevenhagen, dir. 50 to 1 Ten Furlongs Jim Wilson, prod. & dir. (additional composer) Touchback Freedom Films Carissa Buffel, Brian Presley, (additional composer) prods.; Don Handfield, dir. To Have and To Hold Enthuse Entertainment Barbara Divisek, prod.; Ray (additional composer) Bengston, dir. Alone Yet Not Alone Enthuse Entertainment Barbara Divisek, prod.; Ray (additional composer) Bengston, dir. The Liberator Produccionnes Insurgentes Jose Luis Escolar, prod.; Alberto (additional arranger) Arvelo, dir. -

'Jaws'. In: Hunter, IQ and Melia, Matthew, (Eds.) the 'Jaws' Book : New Perspectives on the Classic Summer Blockbuster

This is the accepted manuscript version of Melia, Matthew [Author] (2020) Relocating the western in 'Jaws'. In: Hunter, IQ and Melia, Matthew, (eds.) The 'Jaws' book : new perspectives on the classic summer blockbuster. London, U.K. For more details see: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/the-jaws-book-9781501347528/ 12 Relocating the Western in Jaws Matthew Melia Introduction During the Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium1 Carl Gottlieb, the film’s screenwriter, refuted the suggestion that Jaws was a ‘Revisionist’ or ‘Post’ Western, and claimed that the influence of the Western genre had not entered the screenwriting or production processes. Yet the Western is such a ubiquitous presence in American visual culture that its narratives, tropes, style and forms can be broadly transposed across a variety of non-Western genre films, including Jaws. Star Wars (1977), for instance, a film with which Jaws shares a similar intermedial cultural position between the Hollywood Renaissance and the New Blockbuster, was a ‘Western movie set in Outer Space’.2 Matthew Carter has noted the ubiquitous presence of the frontier mythos in US popular culture and how contemporary ‘film scholars have recently taken account of the “migration” of the themes of frontier mythology from the Western into numerous other Hollywood genres’.3 This chapter will not claim that Jaws is a Western, but that the Western is a distinct yet largely unrecognised part of its extensive cross-generic hybridity. Gottlieb has admitted the influence of the ‘Sensorama’ pictures of proto-exploitation auteur William Castle (the shocking appearance of Ben Gardner’s head is testament to this) as well as The Thing from Another World (1951),4 while Spielberg suggested that they were simply trying to make a Roger Corman picture.5 Critical writing on Jaws has tended to exclude the Western from the film’s generic DNA. -

Baskin-Robbins Celebrates the Start of the Summer Movie and Ice Cream Seasons with the Amazing Spider-Man 2„¢

BASKIN-ROBBINS CELEBRATES THE START OF THE SUMMER MOVIE AND ICE CREAM SEASONS WITH THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2â„¢ Movie Promotion with Sony Pictures Brings Super-Powered New Frozen Treats, Including a Delicious New Flavor of the Month, to Baskin-Robbins, As Well As a Three-Day Scoop Fest Promotion and Amazing Scoop Fest Contest CANTON, Mass. (March 31, 2014) – Baskin-Robbins, the world’s largest chain of ice cream specialty shops, is excited to welcome your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man to its restaurants and the arrival of The Amazing Spider-Man 2 ™ to the big screen on May 2. Starting this week, Baskin-Robbins, in collaboration with Sony Pictures, brings the spirit of The Amazing Spider-Man 2 to participating Baskin-Robbins locations nationwide with a full web of delicious frozen treats and promotions inspired by the blockbuster film franchise, including the April Flavor of the Month, The Amazing Spider-Man 2™ ice cream. “We are excited to help bring the buzz and excitement of The Amazing Spider-Man 2 to Baskin-Robbins guests nationwide through our collaboration with Sony Pictures,” said John Costello, President, Global Marketing and Innovation, Dunkin’ Brands. “It’s a great way to kick off the summer ice cream and movie seasons. We hope guests will swing into our restaurants to try our delicious frozen treats inspired by The Amazing Spider-Man 2, and also take part in our three-day Scoop Fest promotion and Amazing Scoop Fest Contest.” Super-Powered Menu Items To help guests get their Spider-Sense tingling, Baskin-Robbins is offering -

International Theatrical Marketing Strategy

International Theatrical Marketing Strategy Main Genre: Action Drama Brad Pitt Wardaddy 12 Years a Slave, World War Z, Killing Them Softly Moneyball, Inglourious Basterds, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button Shia LaBeouf Bible Charlie Countryman, Lawless, Transformers: Dark of the Moon, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Eagle Eye, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull Logan Lerman Norman Noah, Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters, Stuck in Love, The Perks of being a Wallflower, The Three Musketeers Michael Peña Gordo Cesar Chavez, American Hustle, Gangster Squad, End of Watch, Tower Heist, 30 Minutes or Less CONFIDENTIAL – DO NOT DISTRIBUTE Jon Bernthal Coon-Ass The Wolf of Wall Street, Grudge Match, Snitch, Rampart, Date Night David Ayer Director Sabotage, End of Watch Target Audience Demographic: Moviegoers 17+, skewing male. Psychographic: Fans of historical drama, military fans. Fans of the cast. Positioning Statment At the end of WWII, a battle weary tank commander must lead his men into one last fight deep in the heart of Nazi territory. With a rookie soldier thrust into his platoon, the crew of the Sherman Tank named Fury face overwhelming odds of survival. Strategic Marketing & Research KEY STRENGTHS Brad Pitt, a global superstar. Pitt’s star power certainly is seen across the international market and can be used to elevate anticipation of the film. This is a well-crafted film with standout performances. Realistic tank action is a key interest driver for this film. A classic story of brotherhood in WWII that features a strong leader, a sympathetic rookie, and three other entertaining, unique personalities to fill out the crew. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

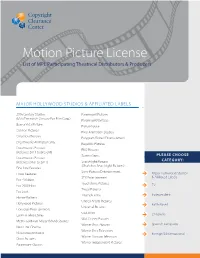

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

Judge Dredd Megazine, #1 to 412

Judge Dredd stories appearing in the Judge Dredd Megazine, #1 to 412 Note: Artists whose names appear after an “&” are colourists; artists appearing after “and” are inkers or other co-artists. Volume One The Boy Who Thought He Art: Barry Kitson & Robin Boutell Wasn't Dated: 26/12/92 America Issue: 19 Issues: 1-7 Episodes: 1 Warhog Episodes: 7 Pages: 9 Issue: 19 Pages: 62 Script: Alan Grant and Tony Luke Episodes: 1 Script: John Wagner Art: Russell Fox & Gina Hart Pages: 9 Art: Colin MacNeil Dated: 4/92 Script: Alan Grant and Tony Luke Dated: 10/90 to 4/91 Art: Xuasus I Was A Teenage Mutant Ninja Dated: 9/1/93 Beyond Our Kenny Priest Killer Issues: 1-3 Issue: 20 Resyk Man Episodes: 3 Episodes: 1 Issue: 20 Pages: 26 Pages: 10 Episodes: 1 Script: John Wagner Script: Alan Grant Pages: 9 Art: Cam Kennedy Art: Sam Keith Script: Alan Grant and Tony Luke Dated: 10/90 to 12/90 Dated: 5/92 Art: John Hicklenton Note: Sequel to The Art Of Kenny Dated: 23/1/93 Who? in 2000 AD progs 477-479. Volume Two Deathmask Midnite's Children Texas City Sting Issue: 21 Issues: 1-5 Issues: 1-3 Episodes: 1 Episodes: 5 Episodes: 3 Pages: 9 Pages: 48 Pages: 28 Script: John Wagner Script: Alan Grant Script: John Wagner Art: Xuasus Art: Jim Baikie Art: Yan Shimony & Gina Hart Dated: 6/2/93 Dated: 10/90 to 2/91 Dated: 2/5/92 to 30/5/92 Note: First appearance of Deputy Mechanismo Returns I Singe the Body Electric Chief Judge Honus of Texas City.