The Naming of Dy Wiebe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

The Canadian Writer & the Iowa Experience

THE CANADIAN WRITER & THE IOWA EXPERIENCE Anthony Bukoski Τ PURPOSE OF THIS PAPER IS TWO-FOLD: to try to piece together from interviewlHsE and correspondence I have had with a number of Canadian authors — twenty-seven to be exact — a sort of general history, a chronological overview of their involvement in the Iowa Writers' Workshop, and to try to assess the significance of that involvement not only to the writers them- selves but to Canadian literature in general. I intend hedging a bit by including some writers who became Canadians only after leaving Iowa.1 Could so many writers have studied at the same institution in the United States without its having left some mark? What attitudes about teaching creative writing or the commitment to the writer's life and craft did they form? Given the method of Workshop investigation, the fragile egos of most young writers, and the fact that the Workshop is in another country, not all of them profited from the experi- ence of studying at Iowa. Speaking of her experiences there in the late 1950's, for instance, Carol Johnson, who teaches at the University of Victoria, noted, "Writ- ers on the whole seem notorious for their unhappiness. Legends of particularly unhappy types prevailed [though not necessarily Canadians]. Since writers are apparently predisposed to neurosis, it would be safe to assume that most of them would be unhappy anywhere."2 Those who were satisfied found the programme valuable, the atmosphere con- ducive to work — though perhaps neither so attractive nor congenial as the main character finds Iowa in W. -

Ties a Canadian Flag Remarkably Close to the One Chosen Two Decades Later

I91 Books in Review buildings, Nobbs designed furniture, coins, letterhead, tombstones, and in the for- ties a Canadian flag remarkably close to the one chosen two decades later. We dis- cover a consistency of philosophy. Nobbs's conviction that 'regionalism in architec- ture was inevitable and therefore a sensible source of inspiration ...,' is paralleled by Traquair's belief that 'architecture is a matter of building to meet real needs with real materials in a real place and therefore regional both from the point of view of its making and its meaning.' One wonders what they would make of the faddish homo- geneity all too evident in today's big cities. All men of strong views and personali- ties, Traquair in particular seems to have been a maverick. 'I think,' wrote a col- league, 'he is our most scholarly yet least academic member ...,' an accolade many would still be pleased to receive. He himself strove to make the architectural curric- ulum as eclectic as possible. 'The longer I work at it the vaguer my ideas become upon standardization....' He went so far as to remark that he would be 'very sorry indeed if the university training ever came to be regarded as the only entrance to the profession.' Physically these are attractive volumes. Care has obviously been taken with the choice of illustration. The pages are well laid out, the elements of each record are distinct, and the font is clear and readable. The inevitable typographical errors are few in number, and do not detract from a favourable overall imipression. If this reviewer has a concern it is a question of durability. -

Swept Under: Reading the Stories of Two Undervalued Maritime Writers

Swept Under: Reading the Stories of Two Undervalued Maritime Writers David Creelman n the past ten years, fiction from the Maritime provinces has topped bestseller lists across North America and Europe. Alistair MacLeod’s No Great Mischief, David Adams Richards’s Mercy amongI the Children, and Ann-Marie MacDonald’s Fall on Your Knees have enjoyed international success and have stimulated interest in the fictions being produced in the Maritime region. But if some novels have broken through and attained critical acclaim and popular suc- cess, other Maritime texts have slipped into comparative obscurity. Of course, not every text deserves a wide readership. Maritime writers have been just as prolific in their production of clichéd or pedestrian fictions as the writers of any other region, and there are many mediocre novels that fittingly fade into the shadows. But there are other texts, works of unusual beauty or complexity, that have not received the recogni- tion they deserve. Susan Kerslake’s first two novels, Middlewatch and Penumbra, and Lesley Choyce’s The Republic of Nothing have not won wide critical attention or public interest, though each text is intricate and engaging, both aesthetically and ideologically. The reasons why these novels have been swept aside, or swept under, are complex; how- ever, three factors can be identified as having shaped their reception and reputation. First, they were published by small presses that have had to labour under difficult circumstances to push their product into the Canadian market. Second, the style and mode of the fictions set them outside the mainstream of popular readership. -

Cultural Circulation University of Vienna, 24–26 September 2010

Cultural Circulation University of Vienna, 24–26 September 2010 “Canadian Writers and Authors from the American South—A Dialogue” International Colloquium, Vienna “Cultural Circulation: Canadian Writers and September 24–26, 2010 Authors from the American South—A Dialogue” Friday, September 24: Jacques Pothier (Université de Versailles-St. in the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Sunday, September 26: Quentin): “Northeast by South: Faulkner’s Dr. Ignaz-Seipel-Platz 2 University Campus, Courtyard 8, Unterrichtsraum Yoknapatawpha and Antonine Maillet’s Acadia.” 9.00 a.m. Cultural Export and Exchange 2.00 p.m. Welcome by the Austrian Evening Program: Visit to Heurigen Academy of Sciences and the University Chair: Hans Bak of Vienna Thomas McHaney (Georgia State University): Greetings by “Voice Not Place: North Ca rolina Writer Leon Herbert Matis, Rooke Makes a Success in Canada” former Vice-President of the Academy of Dieter Meindl (University of Erlangen): Sciences, “Import- Export Canada/American South in the H.E. Dr. John Barrett, Saturday, September 25: 2.30 p.m. Continental Dialogues in Short Short Story” Ambassador of Canada in Austria, University Campus, Courtyard 1, Aula Fiction Ian MacRae (Wilfrid Laurier University): Jan Krc, Chair: Alfred Hornung “Inventing the World: Jack Hodgins, and Reading Counselor for Public Affairs, US-Embassy in 9.00 a.m. African Americans and Their the Canadian Historical Imaginary in Southern Vienna, Canadian Destination Reingard Nischik (University of Konstanz): Contexts” Andrea Seidler, “Two Nations, One Genre? The Modernist Short Chair: Carmen Birkle Vice-Dean, Faculty of Philological and Cultural Story in the United States and Canada“ 10.45 a.m. Coffee Break Studies, U of Vienna, Richard J. -

Bridgeman, Joan. Thesis.Pdf (4.565Mb)

-,1~ The University of Man~toba f R ;qg I The "Indian," the "Other" ,5 7~ in the Canadian Quest for Identity by Joan Bridgeman A Thesis Subni tted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English Winnipeg, Manitoba March, 1981 : .. ' ;' · .... '1: i: i'·: . ~ i . •1' '' I' ., "'I THE UNIVERSITY OF, MANITOBA . I • . , I FACULTY OF GRADUATE·STUDIES . " 'i I:' I The under:; igned certify that they ha've read, and recoITTTiend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance, a Master's thesis entitled: ............................................. •- ....... rl'hc Indian, the ''Other'' in the Canadian Quest .................................................................Fo1 Identity Joan Margaret Bridgeman(Hoeppner) submitted hy ............................................ in partii:i fulfilment of the requirements for the degree .cif Master of Arts '/') .I / ~--~ . I/ /1 L. ·:.....:>----------~ . A"'/.'J ... ;. t:. ..... Advisor . '. ~ .. " ,'·. External Examiner Da tc llral Examination is: Satisfactory!){/ Not Required I I [Unless 01r1erwisc specified by the major Department, thesis students 1i1t1st pass ,1n oral examination on the subject of the thesis and matters 1·elatinr; :l":•reto.J : : >1. ·r- I, THE "IND! AN,•: THE "OTHER" ' ,, ' lM THE . '1 CANADIAN QUEST FOR IDENTITY , I BY JOAN BRIDGEMAN .-\ t:it ;;i") ~ub~~1itt..:d \t} 1h 1~' F;1culty of Graduate Stu<lics of ~h1.,- l ,)ly'-·rsity of ;..:aniloha in p:lrtiai fulfilhncnt of the n.:quirL'tt1t11t.s MASTER OF ARTS. © 1981 p,.,:: '""iun I"" lw:·:·, '"""""! 10 the LlllRARY OF TllE UNIVER .Sll Y ';1: MA:\ l'rOll.-\ 10 lend or sell copies of this thesis, to ilk' .'.TIO'\:\L LIBIL\l\l' OF CANADA to inicrofilm this ilh· .: <cl t<> k11d """·II ,·,,:ii:» or the film, and UNIVEHSITY ,\I II I'' i1 J D!S 1u pubfol1 :111 abstract of this thesis. -

Romance and Realism in the Depiction of The

THE PRIMITIVE MYSTIQUE : ROMANCE AND REALISM IN THE DEPICTION OF THE NATIVE INDIAN IN ENGLISH-CANADIAN FICTION A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English by Marjorie Anne Gilbart tRetzleff Saskatoon, Saskatchewan c 1981 . M .A . Gilbart Retzleff The author has agreed that the Library, University of Saskatchewan, may make this thesis freely available for inspection . Moreover, the author has agreed that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised the thesis work recorded herein or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of . the College in which the thesis work was done . It is understood that due recognition will be given to the author of this thesis and to the University of Saskatchewan in any use of the material in this thesis . Copying or publication or any other use of the thesis for financial gain without approval by the University of Saskatchewan and the author's written permission is prohibited . Requests for permission to copy or to make any other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part s hould . be addressed to : Head of the Department of English University of Saskatchewan SASKATOON . Canada . Abstract Although several critics since the nineteenth century have written about the variety of interpretations of the native Indian in English- Canadian literature, no one has yet devoted a full-length study to the way the Indian is depicted in fiction alone . -

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89131-8 - The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This book offers a comprehensive and lively introduction to major writers, genres, and topics in Canadian literature. Addressing traditional assumptions and current issues, contributors pay attention to the social, political, and eco- nomic developments that have informed literary events. Broad surveys of fic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing in a country historically defined by its regions. Also discussed are genres that have a special place in Canadian literature, such as nature-writing, exploration- and travel-writing, and short fiction. Although the emphasis is on literature in English, a substantial chapter on francophone writing is included. Eva-Marie Kroller¨ is Professor at the Department of English, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Her books include Canadian Travellers in Europe (1987), George Bowering: Bright Circles of Colour (1992), the only book on Canada’s first poet laureate currently available, and Pacific Encoun- ters: The Production of Self and Other (coedited, 1997). © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89131-8 - The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More information © in this -

Unit 14 Gabrielle Roy: Life and Works

UNIT 14 GABRIELLE ROY: LIFE AND WORKS Structure 14.0 Objectives 14.1 Life of Gabrielle Roy 14.2 Gabrielle Roy's Works 14.3 Gabrielle Roy's Place in the History of French-Canadian Literature Questions 14.0 OBJECTIVES Here a brief glimpse of Gabrielle Roy's life is offered. She is seen as representative (by and large) of the way Quebec fiction (a part of it anyway) moved. 14.1 LIFE OF GABRIELLE ROY Gabrielle Roy was born on 22 March, 1909 in Saint Boniface, Manitoba. In 1927, the year of her father's death, she enrolled in the Winnipeg Normal Institute. Later she started teaching and from 1930 to 1977 she did school teaching in Saint Boniface. She sailed to London in September 1937 and studied acting. She travelled in Europe (especially France) and started writing articles on Europe and Canada for newspapers back-home. She returned to Canada in 1939 and chose to settle in Montreal. She did a lot of journalism. In 1947 she met and married Marcel Charbotte. With him she travelled to France where she spent the next three years with excursions to other parts of Europe. In 1968, she received an honorary degree from Lava1 University. She died on 13 July, 1983. 14.2 GABRIELLE ROY'S WORKS The titles of Roy's books are: Bonheur D 'occasion (1945) translated as The Tin Flute (1947) La Petitte Poule d'Eau (1950) translated as Where Nests the Water Hen (1950) Alexander Chenevert (1954) translated as The Cashier (1955) Rue Deschambault (1 955) translated as Street of Riches (1957) La Montagne Secrete (1961) translated as The Hidden Mountain (1962) La Route d'Altamont (1966) translated as The Road Past Altamont (1 966) La Riviere sun repos (1970) translated as The Windflower (1970) Cet Ete qui Chantait (1972) Gabrielle Roy: Life translated as Enchanted Summer (1976) and Works Un Jardin au Bout du Monde (1975) translated as Garden in the Wind (1977) Ces Enfants de Ma Vie (1977) translated as Children ofMy Heart (1979) Fragile Lights of Earth (1982) brief detour through some of these works is helpful. -

University of Alberta (Canada)

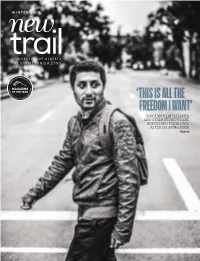

WINTER 2017 UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA ALUMNI MAGAZINE ‘THIS IS ALL THE FREEDOM I WANT’ HOW ABDULLAH ALTAMER AND OTHER STUDENTS ARE REBUILDING THEIR LIVES AFTER ESCAPING SYRIA Page 26 WINTER 2017 ON THE COVER VOLUME 73 NUMBER 3 Even the act of walking to school is meaningful to Abdullah Altamer, one of 14 Syrian students who have come to the U of A through the President’s Award for Refugees and Displaced Persons. Page 26 Photo by John Ulan “ The littlest thing tripped me up in more ways than one.” Whatever life brings your way, small or big, departments take advantage of a range of insurance options 3 at preferential group rates. Your Letters 5 Getting coverage for life-changing events may seem like a Notes What’s new and noteworthy given to some of us. But small things can mean big changes 12 too. Like an unexpected interruption to your income. Alumni Continuing Education insurance plans can have you covered at every stage of life, Column by Curtis Gillespie every step of the way. 16 Whatsoever Things Are True You’ll enjoy affordable rates on Term Life Insurance, Column by Todd Babiak Major Accident Protection, Income Protection Disability, 17 Health & Dental Insurance and others. The protection Thesis There are answers that you need. The competitive rates you want. lie at the intersection of words and images. 43 Get a quote today. Call 1-888-913-6333 or visit us Trails Where you’ve been and at manulife.com/uAlberta. where you’re going 44 features Books 26 46 Seen / Unseen Class Notes After fleeing conflict, three Syrian students embrace 59 the everyday moments. -

Memory and Place in Rudy Wiebe's a Discovery of Strangers

Memory and Place in Rudy Wiebe’s A Discovery of Strangers Monica Bottez University of Bucharest Bucharest, Romania Memory and Place in Rudy Wiebe’s A Discovery of Strangers Memory and place/history and geography are fundamental elements of personal and national identity. Mari Peepre-Bordessa founds her study of Hugh Maclennnan’s National Trilogy on the parallelism between the process of attaining maturity by an individual human being and that of a newly developing nation and she affirms that as “ties to the ‘parent’ state loosened, Canadians learned to identify with their local community, then with their region and finally with their nation” (Peepre-Bordessa 30-31). It is a description that seems to fit the direction in which Rudy Wiebe’s imagination has evolved. At first his imaginative genius was challenged by the fictional rendering of Mennonite communities, the most influential identity factor of his early upbringing: The Blue Mountains of China (1970), Peace Shall Destroy Many (1962). Then, as he kept roaming the wide prairies of his native Saskachewan, his imagination became haunted, as he confessed, by the earlier inhabitants of those places – the Native Indians and the Métis, whose perspective and voice he recreated in the Governor General Award winning The Temptations of Big Bear (1973) and in The Scorched Wood People (1977), concentrating on the official discourse about the time of the Indian Treaty negotiations in the 1870’s and 1880’s and the Louis Riel Northwest Rebellions. A Discovery of Strangers (1994) may be regarded both as a continuation of Wiebe’s imaginative interest in Native people’s spirituality and culture and as a culmination of his older sense of the North as a symbol of Canadian national identity – a notion revealed in his illuminating confession expressed in the Foreword to the River of Stone: Fictions and Memories: (“Love Letters from Land and Sea”): “North and Wilderness.