Laguna Beach and Contemporary TV Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hills Are Alive

18 ★ FTWeekend 2 May/3 May 2015 House Home perfect, natural columns of Ginkgo biloba“Menhir”. Pergolasandterraces,whichdripwith trumpet vine in summer, look down on standing stones and a massive “stone Returning to Innisfree after 15 years, Jane Owen henge”framingthelake. A grass dome, “possibly a chunk of mountain top or some such cast finds out whether this living work of art in down by the glacier that created the lake”, says Oliver, is echoed by clipped New York State retains its magic domes of Pyrus calleryana, the pear nativetoChina. Beyond the white pine woods, the path becomes boggy and narrow, criss- crossed with tree roots, moss and fungi. A covered wooden bridge reminds visi- torsthisisanall-Americanlandscape. Buteventheall-American,maplesyr- The hills up-supplying sugar maples here come with a twist. They are Acer saccharum “Monumentale” and, like the ginkgos, are naturally column-shaped. Innis- free’s American elms went years ago, are alive . victims of Dutch elm disease, but the Hemlocks are hanging on, with the help ofinsecticidetofightthewoollyadelgid. Larger garden pests include beavers, which have built a lodge 100m from the bout 90 miles west of the Iwillariseandgonow,andgoto bubble fountain, and deer. At least the thrumming heart of New Innisfree, . latter has a use, as part of a programme York City is a landscape Ihearlakewaterlappingwithlow of hunters donating food for those in that stirs my soul. I rate soundsbytheshore; need. So the dispossessed eat venison, it along with Villa Lante, WhileIstandontheroadway,oron albeitthetough,end-of-seasonsort. AThe Garden of Cosmic Speculation, thepavementsgrey, All is beautiful, but there’s one Liss Ard in Ireland, Little Sparta, Nin- Ihearitinthedeepheart’score. -

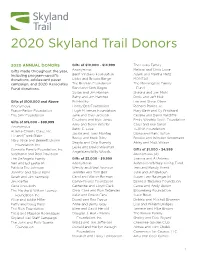

2020 Donor List

2020 Skyland Trail Donors 2020 ANNUAL DONORS Gifts of $10,000 - $14,999 The Lesko Family Gifts made throughout the year, Anonymous Melissa and Chris Lowe including program-specific Banfi Vintners Foundation Adam and Martha Metz donations, adolescent paver Libby and Brooks Barge MONTAG campaign, and 2020 Associates The Breman Foundation The Morningside Family Fund donations. Rand and Seth Hagen Fund Susan and Jim Hannan Shauna and Jim Muhl Patty and Jim Hatcher Doris and Jeff Muir Gifts of $100,000 and Above Ed Herlihy Lee and Steve Olsen Anonymous Honey Bee Foundation Richard Parker, Jr. Fraser-Parker Foundation Hugh M. Inman Foundation Mary Beth and Cy Pritchard The SKK Foundation Jane and Clay Jackson Cecelia and David Ratcliffe Courtney and Kyle Jenks Emily Winship Scott Foundation Gifts of $15,000 - $99,999 Amy and Nevin Kreisler Caryl and Ken Smith Anonymous Betts C. Love TEGNA Foundation Atlanta Charity Clays, Inc. Jackie and Tony Montag Diana and Mark Tipton Liz and Frank Blake Becky and Mark Riley Brooke and Winston Weinmann Mary Alice and Bennett Brown Shayla and Chip Rumely Abby and Matt Wilson Foundation, Inc. Leslie and David Wierman Connolly Family Foundation, Inc. Gifts of $1,000 - $4,999 Angela and Billy Woods Stephanie and Reid Davidson Anonymous (2) The DeAngelo Family Gifts of $5,000 - $9,999 Joanna and Al Adams Nan and Ed Easterlin Anonymous Ashmore-Whitney Giving Fund Patricia Toy Johnson Wendy and Neal Aronson Terri and Randy Avent Jennifer and David Kahn Jennifer and Tom Bell Julie and Jim Balloun Sarah and Jim Kennedy Carol and Walter Berman Susan Lare Baumgartel Jim Kieffer Camp-Younts Foundation Bennett Thrasher Foundation Carla Knobloch Catherine and Lloyd Clark Carrie and Andy Beskin The Martha & Wilton Looney Chris Cline and Ron Rezendes Bloomberg Foundation Foundation Inc. -

The Best Totally-Not-Planned 'Shockers'

Style Blog The best totally-not-planned ‘shockers’ in the history of the VMAs By Lavanya Ramanathan August 30 If you have watched a music video in the past decade, you probably did not watch it on MTV, a network now mostly stuck in a never-ending loop of episodes of “Teen Mom.” This fact does not stop MTV from continuing to hold the annual Video Music Awards, and it does not stop us from tuning in. Whereas this year’s Grammys were kind of depressing, we can count on the VMAs to be a slightly morally objectionable mess of good theater. (MTV has been boasting that it has pretty much handed over the keys to Miley Cyrus, this year’s host, after all.) [VMAs 2015 FAQ: Where to watch the show, who’s performing, red carpet details] Whether it’s “real” or not doesn’t matter. Each year, the VMAs deliver exactly one ugly, cringe-worthy and sometimes actually surprising event that imprints itself in our brains, never to be forgotten. Before Sunday’s show — and before Nicki Minaj probably delivers this year’s teachable moment — here are just a few of those memorable VMA shockers. 1984: Madonna sings about virginity in front of a blacktie audience It was the first VMAs, Bette Midler (who?) was co-hosting and the audience back then was a sea of tux-wearing stiffs. This is all-important scene-setting for a groundbreaking performance by young Madonna, who appeared on the top of an oversize wedding cake in what can only be described as head-to-toe Frederick’s of Hollywood. -

Scout Songs It Goes on and on My Friends

TAPS Day is done, Fading light, Thanks and Praise Opening Songs Gone the sun, dims the sight, For our days; From the lake, And a star ‘Neath the sun, From the hills, gems the sky ‘neath the stars, From the sky, gleaming bright. ‘neath the sky; All is well, safely rest, From afar, As we go, God is nigh. drawing nigh, This we know, fall the night. God is nigh. DAY CAMP CLOSING SONG (Tune: “Yankee Doodle”) And now it’s time to say goodbye, But we won’t feel so blue; ‘Cause soon the time will come again when we’ll be back to see you. Cub Scout day camp’s lots of fun—Games and crafts and singing, So get your pals and join the fun for a week filled to the brimming! SCOUT VESPERS WE’RE ALL TOGETHER AGAIN (Tune: O Tannenbaum) We’re all together again Softly falls the light of day, We’re here, we’re here As our campfire fades away; We’re all together again Silently each Scout should ask, We’re here, we’re here “Have I done my daily task? And who knows when Have I kept my honor bright? We’ll be all together again Can I guiltless sleep tonight? Signing all together again Have I done and have I dared, We’re here, we’re here Everything to be prepared?” 32 1 TAPS Day is done, Fading light, Thanks and Praise Opening Songs Gone the sun, dims the sight, For our days; From the lake, And a star ‘Neath the sun, From the hills, gems the sky ‘neath the stars, From the sky, gleaming bright. -

Path to Rome Walk May 8 to 20, 2018

Path to Rome Walk May 8 to 20, 2018 “A delight—great food and wine, beautiful countryside, lovely hotels and congenial fellow travelers with whom to enjoy it all.” —Alison Anderson, Italian Lakes Walk, 2016 RAVEL a portion of the Via Francigena, the pilgrimage route that linked T Canterbury to Rome in the Middle Ages, following its route north of Rome through olive groves, vineyards and ancient cypress trees. Discover the pleasures of Central Italy’s lesser-known cities, such as Buonconvento, Bolsena, Caprarola and Calcata. With professor of humanities Elaine Treharne as our faculty leader and Peter Watson as our guide, we refresh our minds, bodies and souls on our walks, during which we stop to picnic on hearty agrarian cuisine and enjoy the peace and quiet that are hallmarks of these beautiful rural settings. At the end of our meanderings, descend from the hills of Rome via Viale Angelico to arrive at St. Peter’s Basilica, the seat of Catholicism and home to a vast store of art treasures, including the Sistine Chapel. Join us! Faculty Leader Professor Elaine Treharne joined the Stanford faculty in 2012 in the School of Humanities and Sciences as a Professor of English. She is also the director of the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis. Her main research focuses on early medieval manuscripts, Old and Middle English religious poetry and prose, and the history of handwriting. Included in that research is her current project, which looks at the materiality of textual objects, together with the patterns that emerge in the long history of text technologies, from the earliest times (circa 70,000 B.C.E.) to the present day. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Celebrity News: Kristin Cavallari Reveals Her Third Wedding Anniversary Celebration with Jay Cutler

Celebrity News: Kristin Cavallari Reveals Her Third Wedding Anniversary Celebration With Jay Cutler By Cortney Moore Time sure does fly by! It’s only been three years since former Laguna Beach and The Hills reality TV star, Kristin Cavallari, tied the knot with Chicago Bears quarterback Jay Cutler in a celebrity wedding! In a celebrity interview with The Knot, Cavallari opened up about her third wedding anniversary with the NFL player. “We went to dinner at one of our favorite spots in Chicago called Blackbird, we had a four-course meal and a bottle of wine. I was a happy girl,” Cavallari said. Evidence of the joyous occasion was shown on Instagram, where Cavallari posted a photo of herself blowing a kiss at Cutler, captioned, “Happy anniversary to my man!” This happy celebrity news has us realizing that reality TV star Kristin Cavallari and Chicago Bears quarterback Jay Cutler know how to make a long-lasting relationship work. Cupid discusses below. A Broken Engagement Prior to the 2013 wedding between Cavallari and Cutler, the celebrity couple faced their own set of challenges. The couple got engaged in April 2011, but broke it off three months later. However, their split didn’t last long seeing as they were back together in December of that year. Cavallari detailed the reasons for their split in her book Balancing in Heels, stating, “I always go after what I want in life, with men or otherwise, and I never settle,” she went on to add, “If something doesn’t feel right, I act on it. -

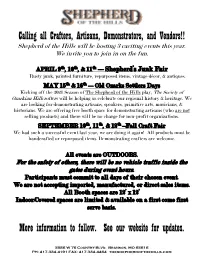

Calling All Crafters, Artisans, Demonstrators, and Vendors!! More Information to Follow. See Our Website for Updates

Calling all Crafters, Artisans, Demonstrators, and Vendors!! Shepherd of the Hills will be hosting 3 exciting events this year. We invite you to join in on the fun. APRIL 9th, 10th, & 11th —Shepherd’s Junk Fair Rusty junk, painted furniture, repurposed items, vintage décor, & antiques. MAY 15th & 16th —Old Ozarks Settlers Days Kicking off the 2021 Season of The Shepherd of the Hills play, The Society of Ozarkian Hillcrofters will be helping us celebrate our regional history & heritage. We are looking for demonstrating artisans, speakers, primitive arts, musicians, & historians. We are offering free booth space for demonstrating artisans (who are not selling products) and there will be no charge for non-profit organizations. SEPTEMBER 10th, 11th, & 12th –Fall Craft Fair We had such a successful event last year, we are doing it again! All products must be handcrafted or repurposed items. Demonstrating crafters are welcome. All events are OUTDOORS. For the safety of others, there will be no vehicle traffic inside the gates during event hours. Participants must commit to all days of their chosen event. We are not accepting imported, manufactured, or direct sales items. All Booth spaces are 12’ x 12’ Indoor/Covered spaces are limited & available on a first come first serve basis. More information to follow. See our website for updates. 5586 W 76 Country Blvd. Branson, MO 65616 PH: 417.334.4191 FAX: 417.334.4464 theshepherdofthehills.com 2021 Vendor Request for Space Early Application ~Circle chosen event(s)~ Shepherd’s Junk Fair Old Ozarks -

Californication Biography Song List What We Play

Californication Biography about us Established in early 2004, Californication the all new Red Hot Chili Peppers Show, aims to deliver Australia’s tribute to one of the world’s most popular and distinguishable bands: the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Californication recreates an authentic and live experience that is, the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The Chili Peppers themselves first came to prominence 20 years ago by fusing funk, rock and rap music styles through their many groundbreaking albums. A typical 90 minute show performed by Californication includes all the big hits and smash anthems that have made the Chili Peppers such an enduring global act. From their breakthrough cover of Stevie Wonder’s Higher Ground to the multiplatinum singles Give it Away, Under the Bridge and Breaking the Girl; as well as Aeroplane, Scar Tissue, Otherside and Californication; fans of the Chili Peppers’ music will never walk away disappointed. Fronted by Johnny, the vocalist of the Red Hot Chili Peppers Show captures all the stage antics and high energy required to emulate Anthony Kiedis, while the rest of the band carry out the very essence of the Red Hot Chili Peppers through the attention of musical detail and a stunning visual performance worthy of the famous LAbased quartet. And now, exclusively supported by the exciting, upcoming party band Big Way Out, you can be guaranteed an enjoyable night’s worth of entertainment. Be prepared to experience Californication the Red Hot Chili Peppers Show. Coming soon to a venue near you! Song List what we play Mothers -

2006 Highlander Vol 88 No 22 March 28, 2006

Regis University ePublications at Regis University Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Archives and Special Collections Newspaper 3-28-2006 2006 Highlander Vol 88 No 22 March 28, 2006 Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation "2006 Highlander Vol 88 No 22 March 28, 2006" (2006). Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper. 205. https://epublications.regis.edu/highlander/205 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Highlander - Regis University's Student-Written Newspaper by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 88, Issu e 22 March 28, 2006 Regis University --- - ----------- e a weekly publication ~1 an er The Jesuit University of the Rockies www.RegisHighlander.com Denver, Colorado Mathematics majors Nobel Laureate Lech Walesa speaks develop pattern in the Field House recognition system Chris Dieterich Erica Easter Editor-in-Chief Staff Reporter "Radishes." That's what former This past summer, senior mathemat President of Poland Lech Walesa ics major, Michael Uhrig, and junior called members of Poland's mathematics and chemistry double Communist Party last Friday evening major, Anthony Giordano, spent their as Regis hosted the former Polish days calculating. But, unlike the president and Nobel Peace Prize everyday calculations involved in fig Laureate in the Field House. "They uring out a tip or balancing a check were red on the outside, but white on book, Uhrig and Giordiano spent the inside." countless hours in a lab, programming One needs a sense of humor, it what would become a working "pattern would seem, to stare down the Soviet recognition" system. -

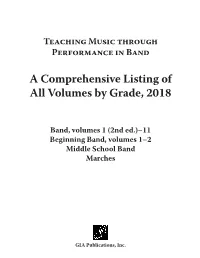

Teaching Music Through Performance in Band

Teaching Music through Performance in Band A Comprehensive Listing of All Volumes by Grade, 2018 Band, volumes 1 (2nd ed.)–11 Beginning Band, volumes 1–2 Middle School Band Marches GIA Publications, Inc. Contents Core Components . 4 Through the Years with the Teaching Music Series . 5 Band, volumes 1 (2nd ed .)–11 . .. 6 Beginning Band, volumes 1–2 . 30 Middle School Band . 33 Marches . .. 36 Core Components The Books Part I presents essays by the leading lights of instrumental music education, written specifically for the Teaching Music series to instruct, inform, enlighten, inspire, and encourage music directors in their daily tasks . Part II presents Teacher Resource Guides that provide practical, detailed reference to the best-known and foundational band compositions, Grades 2–6,* and their composers . In addition to historical background and analysis, music directors will find insight and practical guidance for streamlining and energizing rehearsals . The Recordings North Texas Wind Symphony Internationally acknowledged as one of the premier ensembles of its kind, the North Texas Wind Symphony is selected from the most outstanding musicians attending the North Texas College of Music . The ensemble pursues the highest pro- fessional standards and is determined to bring its audiences exemplary repertoire from all musical periods, cultures, and styles . Eugene Migliaro Corporon Conductor of the Wind Symphony and Regents Professor of Music at the University of North Texas, Eugene Corporon also serves as the Director of Wind Studies, guiding all aspects of the program . His performances have drawn praise from colleagues, composers, and critics alike . His ensembles have performed for numerous conventions and clinics across the world, and have recorded over 600 works featured on over 100 recordings .