Recollections on Singing Messiaen's Saint Francois D'assise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 94, 1974-1975

Saturday Evening March 15, 1975 at 8:00 Carneqie Hall J 974 1975 SEASON \*J NEW YORK The Carnegie Hall Corporation presents the Boston Symphony Orchestra NINETY-FOURTH SEASON 1974-7 5 SEIJI OZAWA, Music Director and Conductor COLIN DAVIS, Principal Guest Conductor OLIVIER MESSIAEN Turangalila-Syntphonie for Piano, Ondes Martenot and Orchestra I. Introduction Modere, un peu vif II. Chant d ' amour 1 Modere, lourd III. Turangalila 1 Presque lent, reveur IV. Chant d'amour 2 Bien modere V. Joie du sang des etoiles Un peu vif, joyeux et passione INTERMISSION VI. Jardin du sommeil d' Amour Tres modere, tres tendre VII. Turangalila 2 Piano solo un peu vif; orchestre modere VIII. Developpement de 1 ' amour Bien modere IX. Turangalila 3 Modere X. Final Modere, avec une grande joie YVONNE LORIOD Piano JEANNE LORIOD Ondes Martenot The Boston Symphony Orchestra records exclusively for Deutsche Grammophon Baldwin Piano Deutsche Grammophon and RCA Records Turangalila-Symphonie for Piano, Ondes Martenot and Orchestra/Olivier Messiaen The Turangalila-Symphonie was commissioned from me by Serge Koussevitzky for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. I wrote and orches- trated it between 17th July, 1946, and 29th November, 1948. The world first performance was given on 2nd December, 1949, in Boston (U.S.A.) Symphony Hall by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. The piano solo part was played by Yvonne Loriod, who has played it in nearly every performance of the work, whoever the conductor or wherever it was given. Turangalila (pronounced with an accent and prolongation of sound on the last two syllables) is a Sanscrit word. -

Dec 08 Pp. 24-25.Indd

Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) 100th Year Anniversary David Palmer “He connects with me in the same way that Bach does.” So said Jack Bruce, the British singer-composer and bassist with the rock group Cream, when asked about the effect of Messiaen’s music on him, after one of the concerts of the big Southbank Festival in London ear- lier this year. “I’m not religious, but the spirituality touches me,” he continued. “There is a spirituality about it that you recognize.”1 So grows the impact of Mes- siaen in this centennial year of his birth, as his unique voice from the last century delivers a message that resonates more and more in the 21st century. Musicians love to use anniversary ob- servances to generate performances and study of composers’ works. Often, these commemorations serve to bring forward less familiar music: last year, we heard Buxtehude’s music far more than usual. Messiaen in the 1930s (photo © Malcolm On the other hand, Bach has received Ball, www.oliviermessiaen.org) three major outpourings in my lifetime: 1950, 1985 and 2000, commemorating either his birth or his death. These festi- vals simply gave us Bach lovers an excuse to play his music more than we usually do (or did)—which was already a lot. Messiaen in our time Coming only 16 years after his death, Messiaen’s 100th anniversary celebra- tions embrace both outcomes. In one way, performances and studies of his out- put have never slackened since his death, unlike many composers who go into eclipse. Great Britain has led the way for some time, and now North America is beginning to take Messiaen into the mainstream. -

MESSIAEN Visions De L’Amen

MESSIAEN Visions de l’Amen DEBUSSY En blanc et noir Ralph van Raat, Piano Håkon Austbø, Piano Claude Debussy (1862-1918): En blanc et noir (1915) Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992): Visions de l’Amen (1943) colouring, Messiaen carried out bold renewals in the Bird-song, at that time, played an increasingly Both works on this recording, milestones in the repertoire dancing quality of the first and by the witty, albeit realm of musical time. As he often said, “rhythm is important rôle in Messiaen’s music. He transcribed this as for two pianos, were composed in wartime at crucial somewhat sarcastic, elegance of the third. colouring of time”, and, correspon dingly, the blue-violet heard in nature, adapting the intervals to the instruments. points in the composers’ lives. Messiaen, in another war, returned to Paris in 1941 theme played by the second piano in the opening as well In No. 5 they are preceded by the pure unison of the Debussy passed the summer of 1915 at Pourville on from war imprisonment, where he had written the Quatuor as in the closing piece, is framed by a rhythmic pedal, Angels and the Saints. Finally, No. 6 expresses the the Normandy coast. He was struggling with his health pour la Fin du Temps (Quartet for the End of Time). played in the extreme registers by the first piano. In the harshness of the Judgement of the damned, before the and suffering from the horrors of the war and from the Having taken on a job as harmony professor at the first piece, the rhythm is a combination of five rhythmical joy of the last piece breaks out. -

Songs of Faith and Love: a Study of Olivier Messiaen's

SONGS OF FAITH AND LOVE: A STUDY OF OLIVIER MESSIAEN’S POÈMES POUR MI By Emily M. Bennett Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Julia Broxholm ________________________________ Co-Chairperson University Distinguished Professor Joyce Castle ________________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ________________________________ Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Michelle Hayes Date Defended: April 1, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Emily M. Bennett certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: SONGS OF FAITH AND LOVE: A STUDY OF OLIVIER MESSIAEN’S POÈMES POUR MI ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Julia Broxholm ________________________________ Co-Chairperson University Distinguished Professor Joyce Castle Date approved: April 1, 2016 ii ABSTRACT It is my determination that Oliver Messiaen’s first song cycle, Poèmes pour Mi (1936), exhibits nearly all of the representative musical and literary devices of the composer’s arsenal: musical and poetic symbols and symmetry, asymmetric and exotic rhythms, color and harmony, and is inspired by his Catholic faith, and must therefore be regarded as among the composer’s most significant early vocal works. After outlining a brief biography and an overview of the work and its premiere, the subsequent analysis covers the compositional techniques and thematic devices are presented, including specific discussion of spirituality, numerical symbols, modal vocabulary, musical colors, and the “Boris motif.” A description of the cycle follows, highlighting important aspects of each piece as they relate to Messiaen’s style. Musical examples appear where relevant iii BIOGRAPHY Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen, born 10 December 1908 in Avignon, France, was pre-destined to be a creative force in the world. -

The Turangalîla-Symphonie

with the Nashville Symphony CLASSICAL SERIES FRIDAY & SATURDAY, MAY 17 & 18, AT 8 PM NASHVILLE SYMPHONY GIANCARLO GUERRERO, conductor JEAN-YVES THIBAUDET, piano CYNTHIA MILLAR, ondes Martenot Introduction to Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie with musical demonstrations – INTERMISSION – OLIVIER MESSIAEN Turangalîla-Symphonie for Piano, Ondes Martenot and Orchestra Introduction: Modéré, un peu vif Chant d'amour 1: Modéré, lourd Turangalîla 1: Presque lent, rêveur Chant d'amour 2: Bien modéré Joie du sang des étoiles: Un peu vif, joyeux et passioné Jardin du sommeil d'amour: Très modéré, très tendre Turangalîla 2: Piano solo un peu vif: orchestre modéré Développement de l'amour: Bien modéré Turangalîla 3: Modéré Final: Modéré, avec une grande joie Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano Cynthia Millar, ondes Martenot This concert will last 2 hours and 20 minutes, including a 20-minute intermission. INCONCERT 39 TONIGHT’S CONCERT AT A GLANCE OLIVIER MESSIAEN Turangalîla-Symphonie • French composer Messiaen occupies a singular role as a trailblazer for the avant-garde who was at the same time profoundly respectful of Western musical tradition. He created a wholly original body of work, of which Turangalîla-Symphonie and The Quartet for the End of Time are his best-known compositions. The latter work was written while he was held in a German prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. • Messiaen’s influence has been profound, extending not only to his students Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, who would go on to revolutionize modern music, but also to popular artists including Rufus Wainwright and Radiohead, whose music owes a particular debt to the composer. -

Messiaen As Pianist: a Romantic in a Modernist World Christopher Dingle

© Copyrighted Material Chapter 2 Messiaen as Pianist: A Romantic in a Modernist World Christopher Dingle Scholars or performers might view the study of musical performance, whether live or recorded, as the exploration of creative confusion. Such an investigation feeds off the gap between the information provided by the composer (principally, though not exclusively, through the score) and the performer’s understanding of what is and is not conveyed explicitly and implicitly by that information. We might rationally think that such a gap would not exist when the composer and the performer are the same individual. Still, while every case differs, the gap can often appear to become a yawning chasm for composer-performers. This chapter explores the particular creative confusion that arises between the composer Olivier Messiaen and the performer Olivier Messiaen. Pierre Boulez, admittedly talking about Messiaen’s position in general, neatly encapsulated the conundrum in words readily applicable to Messiaen the performer. He described Messiaen as: a man who is preoccupied strongly with techniques, but who puts forward, in the first place, expression … . He has a kind of revolutionary ideal and at the same time a very conservative taste for what the essence of music is … . [T]hat’s a man who is exactly in the centre of some very important contradictions of this century.1 These contradictions become especially acute in considering Messiaen as composer-performer. Messiaen the composer was a man of many words, always happy to talk about his music. Despite the widespread availability of certain recordings, Messiaen the performer is rather less well known. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00031-5 — Olivier Messiaen's Catalogue d'oiseaux Roderick Chadwick , Peter Hill Excerpt More Information 1 I n t r o d u c t i o n In March 1948 Olivier Messiaen gave an interview to the newspaper France- Soir . He seemed at ease with life and, with the Turangalîla- Symphonie about to be i nished, he spoke of his plans for an opera with a freedom unthink- able in later years, when he would become cautious and secretive about work in progress. When asked which musicians had most inl uenced him the conversation took an unexpected turn: h e birds. Excuse me? Yes, the birds. I’ve listened to them ot en, when lying in the grass pencil and note- book in hand. And to which do you award the palm? To the blackbird, of course! It can improvise continuously eleven or twelve dif erent verses, in each of which identical musical phrases recur. What freedom of inven- tion, what an artist! 1 In the event there was to be no opera, at least not for another thirty- i ve years. Instead, Messiaen went through a period of experiment, prompted initially by a desire to develop his own version of serialism. h e trans- formation of his music moved into a second phase from 1952 when, tak- ing his cue from the France- Soir interview, he embarked on a decade in which almost all his music was inspired by the study of birds and bird- song. Messiaen ’ s belief that birdsong is music gave him a sense of mission to bring that music within the scope of human understanding. -

Olivier Messiaen: Musique Et Couleurs: Nouveaux Entretiens Avec Claude Samuel

Book Reviews Claude Samuel. Olivier Messiaen: Musique et couleurs: Nouveaux entretiens avec Claude Samuel. Paris: Editions Belfond, 1986. Translated by E. Thomas Glasow as Olivier Messiaen: Music and Color: Conversations with Claude Samuel. Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1994. Reviewed by Vincent Benitez I feel that rhythm is the primordial and perhaps essential part of music; I think it most likely existed before melody and harmony, and in fact I have a secret preference for this element. I cherish this preference all the more because I feel it distinguished my entry into contemporary music. (67) Olivier Messiaen's compositional achievements in rhythmic processes and organization rank him as one of the twentieth century's leading innovators in this area, influencing composers such as Boulez and Stockhausen. Drawing from diverse sources such as Greek meters, Indian deff-talas, Japanese temporal concepts, Beethoven (development i by elimination ), and Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, Messiaen forged a temporal language that infused a distinctive sound and style to his music. One must note, however, that Messiaen's innovations were not limited to the rhythmic field alone. The symmetrical framework of his modes of limited transpositions and the uses of birdsong, plainchant, added-note chords, and sound/color relationships in his music are just some examples of his creativity in the areas of pitch, texture, and timbre. Messiaen drew analogies between his procedures in both rhythmic and pitch domains. For example, in his Chronochromie for orchestra (1959-60), Messiaen used symmetrical permutations, a IThis procedure consists of gradually withdrawing notes from a musical idea until its basic essence is exposed. -

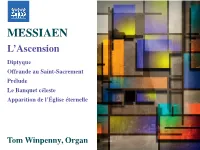

573471 Bk Messiaen EU

MESSIAEN L’Ascension Diptyque Offrande au Saint-Sacrement Prélude Le Banquet céleste Apparition de l’Église éternelle Tom Winpenny, Organ Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Composed in 1928 or 1930, Diptyque is dedicated to days before the première of the orchestral version (1932- L’Ascension and other works Dukas and Dupré and is subtitled ‘Essai sur la vie 33). This extraordinary work was praised by the music terrestre et l’éternité bienheureuse’ (‘Essay on earthly life press and immediately established Messiaen as one of the Olivier Messiaen was a towering figure in 20th century During his student years Messiaen began deputising at and blissful eternity’). The restless first section depicts the most important composers of his generation. The opening European music. His highly-personal musical language La Trinité for the ailing organist Charles Quef. Messiaen was anxieties of earthly life: the opening seven-note theme movement, Majesté du Christ, presents a series of solemn drew heavily on the natural world, the music of Eastern already gaining recognition as a composer (his first recurs frequently, and at the climax it is heard in canon phrases, played on the reed stops, depicting Christ’s prayer cultures and, above all, his devout Catholicism. A talented published work, Préludes for piano, was issued in 1930), and between manuals and pedal. Throughout, the harmony is to his Father. Centred on the note B, the relatively static pianist, Messiaen entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1919 the richly-voiced orchestral colours of the church’s Cavaillé- highly chromatic, though it retains a tonal centre: its style harmony is combined with steady, undulating rhythms and at a remarkably early age, and in 1927 joined Marcel Coll instrument were undoubtedly an inspiration for him as a is redolent of the work’s dedicatees. -

Quant Aux Voies D'ascension Du Jeune Messiaen

Quant aux voies d’ascension du jeune Messiaen (1936-1945) Jacques Amblard To cite this version: Jacques Amblard. Quant aux voies d’ascension du jeune Messiaen (1936-1945). 2021. hal-03164402 HAL Id: hal-03164402 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03164402 Preprint submitted on 9 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Quant aux voies d’ascension du jeune Messiaen (1936-1945) Jacques Amblard LESA EA-3274 Aix Marseille Université Abstract : La période de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale aura été un moment clef dans l’ascension du jeune Messiaen. Mise en loge dramatique mais féconde pour le compositeur ? Compromission avec le gouvernement provisoire ? Est-ce le fait d’être devenu professeur au Conservatoire de Paris et d’y avoir trouvé une armée de futurs soldats pour la défense de son œuvre, celle d’un « capitaine admiré » ? Ce texte est paru dans Euterpe, n°35, juillet 2020, p. 23-28. Ceci en est une version modifiée. Olivier Messiaen aura été un remarquable médiateur de son œuvre. Notamment, sciemment ou non, il se sera souvent tenu « sur la médiatrice ». Au centre1. Entre diatonisme et chromatisme 2 . -

Download Booklet

La Mer Bleue Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Catalogue d’oiseaux, Book 1: 1 No. 1 Le Chocard des Alpes 10:06 2 No. 2 Le Loriot 8:08 3 [Interlude: Song Thrush and Thekla Larks] 2:41 4 No. 3 Le Merle bleu 13:51 5 [Interlude: Golden Oriole and Garden Warbler] 1:56 David Gorton (b.1978) 6 Ondine 8:14 Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) Piano Sonata No. 3, Op. 36 19:12 7 I. Presto – 7:22 8 II. Adagio, mesto – 4:21 9 III. Assai vivace, scherzando – 1:07 10 IV. Fuga: Allegro moderato, scherzando e buffo 6:21 11 [Postlude] 1:17 Total playing time: 65:27 Roderick Chadwick piano Interludes & Postlude: Peter Sheppard Skærved and Shir Victoria Levy (violins) La Mer Bleue ‘Music needs to be Mediterraneanised’ – Friedrich Nietzsche The Case of Wagner The first book of Olivier Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux (1958) begins with an Alpine chough’s ‘tragic solitary cry’ and ends with a Mediterranean womens’ chorus. It is a journey towards sunlight, colour and company, from mountain to coastline, from rhythmic machinations to nostalgic added sixth hamonies – and, it is tempting to say, from masculine to feminine. There is evidence to support this last notion: four times in ‘Le Merle bleu’ a memorable progression of rising, arpeggiated chords evokes, according to the score, ‘La mer bleue’: a pun on the titular bird, a nod towards Debussy, and perhaps a Marian presence too – if so, a rare acknowledgement of Messiaen’s faith in an outwardly secular work. Though a repetitious feature, these four refrains also steer us subtly through the piece, the longest and structurally most complex of the three. -

Open Thesis FINAL__Corrected .Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Music A NEWLY DISCOVERED COMPOSITIONAL APPROACH TO BIRDSONG: LA FAUVETTE PASSERINETTE OF OLIVIER MESSIAEN A Thesis in Music by Quentin M. Jones ©2017 Quentin M. Jones Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts December 2017 The thesis of Quentin M. Jones was reviewed and approved* by the following: Vincent P. Benitez Associate Professor of Music Thesis Advisor Maureen A. Carr Distinguished Professor of Music Marica S. Tacconi Professor of Musicology Associate Director for Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the School of Music ii Abstract While working with Messiaen’s birdsong notebooks in 2012, Peter Hill discovered a new birdsong composition for solo piano, spread out over three separate notebooks (Mss 23020, 23023, 23072). He then put the piece together based on the composer’s indications. Published by Faber Music in 2015 as La Fauvette Passerinette (Subalpine Warbler), this avian-inspired piece of Messiaen allows a new and enticing look into his musical world. In this thesis, I examine La Fauvette Passerinette, uncovering its unique formal construction, as well as dense and colorful harmonic language. I also explore its programmatic nature and poetic symbolism, relating it to Messiaen’s birdsong music in general. iii Table of Contents List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………..v List of Musical Examples………………………………………………………………………...vi List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………………….vii Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………..viii