Development of a Simple Algorithm to Guide the Effective Management of Traumatic Cardiac Arrest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIMS 508 Stillwater Flood Search and Rescue Team

Resource Typing Definition for Response Mass Search and Rescue Operations STILLWATER/FLOOD SEARCH AND RESCUE TEAM DESCRIPTION The Stillwater/Flood Search and Rescue (SAR) Team conducts search, rescue, and recovery operations for humans and animals in stillwater and stillwater/flood environments RESOURCE CATEGORY Search and Rescue RESOURCE KIND Team OVERALL FUNCTION The Stillwater/Flood SAR team: 1. Searches for and rescues individuals who may be injured or otherwise in need of medical attention 2. Provides emergency medical care, including Basic Life Support (BLS) 3. Provides animal rescue 4. Transports humans and animals to the nearest location for secondary land or air transport 5. Provides shore-based and boat-based water rescue for humans and animals 6. Supports helicopter rescue operations and urban SAR in water environments for humans and animals 7. Operates in environments with or without infrastructure, including environments with disrupted access to roadways, utilities, transportation, and medical facilities, and with limited access to shelter, food, and water COMPOSITION AND ORDERING 1. Requestor and provider address certain needs and issues prior to deployment, including: SPECIFICATIONS a. Communications equipment that enables more than intra-team communications, such as programmable interoperable communications equipment with capabilities for command, logistics, military, air, and so on b. Type of incident and operational environment, such as weather event, levy or dam breach, or risk of hazardous materials (HAZMAT) contamination c. Additional specialized personnel, such as advanced medical staff, animal SAR specialists, logistics specialists, advisors, helicopter support staff, or support personnel for unique operating environments d. Additional transportation-related needs, including specific vehicles, boats, trailers, drivers, mechanics, equipment, supplies, fuel, and so on e. -

Basic Life Support Health Care Provider

ELLIS & ASSOCIATES Health Care Provider Basic Life Support MEETS CURRENT CPR & ECC GUIDELINES Ellis & Associates / Safety & Health HEALTH CARE PROVIDER BASIC LIFE SUPPORT - I Ellis & Associates, Inc. P.O. Box 2160, Windermere, FL 34786-2160 www.jellis.com Copyright © 2016 by Ellis & Associates, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. Ellis & Associates P.O. Box 2160, Windermere, FL 34786-2160 Ordering Information: Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, trade bookstores and wholesalers. For details, contact the publisher at the address above. Disclaimer: The procedures and protocols presented in this manual and the course are based on the most current recommendations of responsible medical sources, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) 2015 Guidelines for CPR & ECC. Ellis & Associates, however, make no guarantee as to, and assume no responsibility for, the correctness, sufficiency, or completeness of such recommendations or information. Additional procedures may be required under particular circumstances. Ellis & Associates disclaims all liability for damages of any kind arising from the use of, reference to, reliance on, or performance based on such information. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Not Available at Time of Printing ISBN 978-0-9961108-0-8 Unless otherwise indicated on the Credits Page, all photographs and illustrations are copyright protected by Ellis & Associates. -

Initial Capnography Values and Resuscitation Outcomes of Patients Assisted by Basic Life Support Units in First Instance

Submitted: 09 December, 2020 Accepted: 05 February, 2021 Published: 08 July, 2021 DOI:10.22514/sv.2021.099 ORIGINALRESEARCH Initial capnography values and resuscitation outcomes of patients assisted by basic life support units in first instance; descriptive prospective study Francisco José Cereceda-Sánchez1;*, Jaume Ponce-Taylor1, Pedro Montero-París1, Iñaki Unzaga-Ercilla1, Natalia Martinez-Cuellar1, Jesús Molina-Mula2 1SAMU 061 Baleares, C/Illes Balears sn. Abstract Palma de Mallorca, 07014, Spain Introduction: Understanding the key factors which affect out hospital cardiac arrest 2Phd Department of Nursing and Physiotherapy University of Balearic (OHCA) outcomes is essential in order to promote patient treatment. The main Islands, Ctra. De Valldemossa, km 7,5 objective of this research was to describe the correlations between the capnographic Palma de Mallorca (Islas Baleares), values obtained during the first minute of monitoring on cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 07122, Spain assisted by basic life-support units, with the results as return of spontaneous circulation *Correspondence (ROSC) and alive hospital admission. The secondary objectives were to describe the [email protected] sociodemographic characteristics of the patients assisted, and to analyze any correlations (Francisco José Cereceda-Sánchez) between receiving basic life-support units and/or defibrillation prior to the arrival of basic life-support units, and the results of the cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers. Methods: A prospective, descriptive, observational study of adult non-traumatic out hospital cardiac arrest patients was conducted. The patients were initially assisted by basic life-support units on the island of Mallorca, with one minute of initial capnography monitoring. Results: From July 2018 to March 2020, fifty-nine patients meeting the inclusion criteria were assisted, 76% were men and their mean age was 64.45 (15.07) years old. -

NYS CFR Protocols

New York State Department of Health Bureau of Emergency Medical Services Statewide Basic Life Support Adult & Pediatric Treatment Protocols Certified First Responder 2003 = Preface and Acknowledgments The 2003 New York State (NYS) Statewide Basic Life Support Adult & Pediatric Treatment Protocols for the Certified First Responder (CFR) includes revisions to match the current New York State CFR course curricula. These 2003 statewide protocols also include de- emphasizing the use of CUPS. CUPS is no longer required to be taught in NYS Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Courses and is not tested in Practical Skills Examinations or State Written Certification Examinations. We would like to acknowledge the members of the New York State EMS Council’s Medical Standards Committee for the time and effort given to developing this set of protocols. In addition, we would like to recognize the efforts of the Regional Emergency Medical Advisory Committees (REMACS) for their input and review. Mark Henry, MD, FACEP Medical Director Edward Wronski, Director State Emergency Medical Advisory Committee Bureau of Emergency Medical Services NYS CFR Basic Life Support Protocols NYS CFR Basic Life Support Protocols Introduction The 2003 NYS Statewide Basic Life Support Adult and Pediatric Treatment Protocols designed by the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services of the New York State Department of Health and the New York State Emergency Medical Services Council. These protocols have been reviewed and approved by the New York State Emergency Medical Advisory Committee (SEMAC) and the New York State Emergency Medical Services Council (SEMSCO). The protocols reflect the current minimally acceptable statewide treatment standards for adult and pediatric basic life support (BLS) used by the Certified First Responder (CFR). -

Basic Life Support Patient Care Standards

This document contains both information and navigation buttons. To read information, use the Down Arrow from a form field. Basic Life Support Patient Care Standards Version 3.0.1 Comes into force December 11, 2017 Emergency Health Services Branch Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care To all users of this publication: The information contained in the Standards has been carefully compiled and is believed to be accurate at date of publication. For further information on the Basic Life Support Patient Care Standards, please contact: Emergency Health Services Branch Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care 5700 Yonge Street, 6th Floor Toronto, ON M2M 4K5 416-327-7900 © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016 Document Control Version Date of Issue Comes into Force Brief Description of Change Number Date 3.0 July 2016 N/A (amended prior Full update. See accompanying training to in force date) bulletin for further details 3.0.1 November 2016 December 11, 2017 Update to Paramedic Prompt Card for Acute Stroke Protocol: Contraindication changed from “CTAS Level 2” to “CTAS Level 1”. Table of Contents Preamble ............................................................................................................................. 7 Preface............................................................................................................................................. 1 Definitions....................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

Basic Life Support 1 1.2 Advanced Life Support 5

RESUSCITATION Edited by Conor Deasy SECTION 1 1.1 Basic life support 1 1.2 Advanced life support 5 1.1 Basic life support Sameer A. Pathan compressions and rapid defibrillation, which ESSENTIALS significantly improves the chances of survival from ventricular fibrillation (VF) in OHCA.1–3 CPR 1 A patient with sudden out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) requires activation of plus defibrillation within 3 to 5 minutes of collapse the Chain of Survival, which includes early high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation following VF in OHCA can produce survival rates (CPR) and early defibrillation. The emergency medical dispatcher plays a crucial and as high as 49% to 75%.5–7 Each minute of delay central role in this process. before defibrillation reduces the probability of survival to hospital discharge by 10% to 12%.2,3 2 Over telephone, the dispatcher should provide instructions for external chest The final links in the Chain of Survival are effec- compressions only CPR to any adult caller wishing to aid a victim of OHCA. This approach tive ALS and integrated post-resuscitation care has shown absolute survival benefit and improved rates of bystander CPR. targeted at optimizing and preserving cardiac 8 3 In the out-of-hospital setting, bystanders should deliver chest compressions to any and cerebral function. unresponsive patient with abnormal or absent breathing. Bystanders who are trained, able, and willing to give rescue breaths should do so without compromising the main focus on high quality of chest compressions. Development of protocols Any guidelines for BLS must be evidence based 4 Early defibrillation should be regarded as part of Basic Life Support (BLS) training, as and consistent across a wide range of providers. -

Part 2: Adult Basic Life Support

Resuscitation (2005) 67, 187—201 Part 2: Adult basic life support International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation The consensus conference addressed many decrease interruptions in compressions.During questions related to the performance of basic two-rescuer CPR of the infant or child, health- life support.These have been grouped into (1) care providers should use a 15:2 compression— epidemiology and recognition of cardiac arrest, ventilation ratio. (2) airway and ventilation, (3) chest compression, • During CPR for a patient with an advanced air- (4) compression—ventilation sequence, (5) postre- way (i.e. tracheal tube, Combitube, laryngeal suscitation positioning, (6) special circumstances, mask airway [LMA]) in place, deliver ventilations (7) emergency medical services (EMS) system, at a rate of 8—10 per min for infants (excepting and (8) risks to the victim and rescuer.Defibril- neonates), children and adults, without pausing lation is discussed separately in Part 3 because during chest compressions to deliver the ventila- it is both a basic and an advanced life support tions. skill. There have been several important advances in the science of resuscitation since the last ILCOR Epidemiology and recognition of cardiac review in 2000.The following is a summary of the arrest evidence-based recommendations for the perfor- mance of basic life support: Many people die prematurely from sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), often associated with coronary heart • Rescuers begin CPR if the victim is unconscious, disease.The following section summarises the bur- not moving, and not breathing (ignoring occa- den, risk factors, and potential interventions to sional gasps). reduce the risk. • For mouth-to-mouth ventilation or for bag-valve- mask ventilation with room air or oxygen, the res- Epidemiology cuer should deliver each breath in 1 s and should see visible chest rise. -

Basic Life Support Health Care Provider

ELLIS & ASSOCIATES Health Care Provider Basic Life Support MEETS CURRENT CPR & ECC GUIDELINES Ellis & Associates / Safety & Health HEALTH CARE PROVIDER BASIC LIFE SUPPORT - I Ellis & Associates, Inc. P.O. Box 2160, Windermere, FL 34786-2160 www.jellis.com Copyright © 2016 by Ellis & Associates, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. Ellis & Associates P.O. Box 2160, Windermere, FL 34786-2160 Ordering Information: Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, trade bookstores and wholesalers. For details, contact the publisher at the address above. Disclaimer: The procedures and protocols presented in this manual and the course are based on the most current recommendations of responsible medical sources, including the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) 2015 Guidelines for CPR & ECC. Ellis & Associates, however, make no guarantee as to, and assume no responsibility for, the correctness, suiciency, or completeness of such recommendations or information. Additional procedures may be required under particular circumstances. Ellis & Associates disclaims all liability for damages of any kind arising from the use of, reference to, reliance on, or performance based on such information. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Not Available at Time of Printing ISBN 978-0-9961108-0-8 Unless otherwise indicated on the Credits Page, all photographs and illustrations are copyright protected by Ellis & Associates. -

Emerging Uses of Capnography in Emergency Medicine in Emergency Capnography Uses of Emerging

Emerging Uses of Capnography in Emergency Medicine WHITEPAPER INTRODUCTION The Physiologic Basis for Capnography Capnography is based on a discovery by chemist Joseph Black, who, in 1875, noted the properties of a gas released during exhalation that he called “fixed air.” That gas—carbon dioxide (CO2)—is produced as a consequence of cellular metabolism as the waste product of combining oxygen and glucose to produce energy. Carbon dioxide exits the body via the lungs. The concentration of CO2 in an exhaled breath reflects cardiac output and pulmonary blood flow as the gas is transported by the venous system to the right side of the heart and then pumped into the lungs by the right ventricle. Capnographs measure the concentration of CO2 at the end of each exhaled breath, commonly known as the end- tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2). As long as the heart is beating and blood is flowing, CO2 is delivered continuously to the lungs for exhalation. An EtCO2 value outside the normal range in a patient with normal pulmonary blood flow indicates a problem with ventilation that may require immediate attention. Any deviation from normal ventilation quickly changes EtCO2, even when SpO2—the indirect measurement of oxygen saturation in the blood—remains normal. Thus, EtCO2 is a more sensitive and rapid indicator of ventilation problems than SpO2.1 Why EtCO2 Monitoring Is Important It is generally accepted that EtCO2 monitoring is the practice standard for determining whether endotracheal tubes are correctly placed. However, there are other important indications for its use as well. Ventilatory monitoring by EtCO2 measurement has long been a standard in the surgical and intensive care patient populations. -

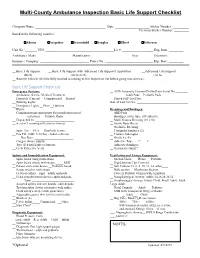

Basic Life Support Checklist

Multi-County Ambulance Inspection Basic Life Support Checklist Company Name: ___________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Sticker Number: __________ Previous Sticker Number: _________ Based in the following counties: Adams Arapahoe Broomfield Douglas Elbert Jefferson Unit No.: _______ VIN: __________________________________________Lic #: ___________________ Exp. Date: _________ Ambulance Make: _____________________ Manufacturer: ________________________ Year: ________ Odometer: _________ Insurance Company: ______________________________ Policy No.: _____________________________ Exp. Date: _________ __Basic Life Support __Basic Life Support with Advanced Life Support Capabilities __Advanced Life Support (BLS) (BLS/ALS) (ALS) __ Reserve Vehicle (Will be fully stocked according to this Inspection list before going into service.) Basic Life Support Check List Emergency Systems: __ AED-Automatic External Defibrillator Serial No ________ __ Ambulance Service Medical Treatment __Adult Pads __Pediatric Pads Protocols (Current) __Computerized __Printed __ Passed Self-Test Date:____________ __ Running Lights Date of Last Service: _________________________________ __ Emergency Lights __Siren __Opticom __Wipers Dressings and Bandages: __ Communications appropriate for jurisdiction served. __ ABD Pads __cell phone __ Portable Radio __ Bandages, roller type, self-adhesive __ Dispatched by: _________________________ __ Multi Trauma Dressing (10 x 36) __ A set of 3 warning reflectors or devices. __ Sterile Burn Sheets ______________________________________ -

CPR Quality: Improving Cardiac Resuscitation Outcomes Both Inside and Outside the Hospital

CPR Quality: Improving Cardiac Resuscitation Outcomes Both Inside and Outside the Hospital A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Peter A. Meaney, MD, MPH, Chair; Bentley J. Bobrow, MD, FAHA, Co-Chair; Mary E. Mancini, RN, PhD, FAHA; Jim Christenson, MD; Allan R. de Caen, MD; Farhan Bhanji, MD, FAHA; Benjamin S. Abella, MD, MPhil, FAHA; Monica E. Kleinman, MD; Dana Edelson, MD, MS, FAHA; Robert A. Berg, MD, FAHA; Tom P. Aufderheide, MD, FAHA; Venu Menon, MD, FAHA; Marion Leary, BSN, RN; on behalf of the CPR Quality Summit investigators Endorsed by the National Association of EMS Physicians, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society of Critical Care Medicine, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Abstract The 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care increased the focus on methods to ensure that high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is performed in all resuscitation attempts. There are 5 critical components of high-quality CPR: minimize interruptions in chest compressions, provide compressions of adequate rate and depth, avoid leaning between compressions, and avoid excessive ventilation. Although it is clear that high-quality CPR is the primary component in influencing survival from cardiac arrest, there is considerable variation in monitoring, implementation, and quality improvement. As such, CPR quality varies widely between systems and locations. Victims often do not receive high-quality CPR due to provider ambiguity in prioritization of resuscitative efforts during an arrest. This ambiguity also impedes the development of optimal systems of care to increase survival from cardiac arrest. This consensus statement addresses the following key areas of CPR quality for the trained rescuer: metrics of CPR performance; monitoring, feedback, and integration of the patient’s response to CPR; team- level logistics to ensure performance of high-quality CPR; and continuous quality improvement on provider, team, and systems levels. -

Resuscitation Policy and Recognition of Life Extinct

RESUSCITATION POLICY AND RECOGNITION OF LIFE EXTINCT South Central Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust Unit 7 & 8, Talisman Business Centre, Talisman Road, Bicester, Oxfordshire, OX26 6HR This Policy is to be read in conjunction with Operational Policies and Procedures No 7 - SCAS Attendance at Sudden Death in Adults (Appendix 8) DOCUMENT INFORMATION Author: Dave Sherwood, Assistant Director of Patient Care Professor Charles Deakin, Divisional Medical Director Resuscitation Lead Reviewed 22nd January 2020 Mark Ainsworth-Smith Jennifer Saunders Number CSPP No. 3 Consultation & Approval: Staff Consultation Process: (21 days) ends 19th Oct 2007 Clinical Review Group: 2nd July 2020 Quality and Safety Committee: 5th June 2010 Board Ratification: N/A This document replaces: SCAS Recognition of Life Extinct Policy Version 1 June 2007 Notification of Policy Release: All Recipients e-mail Staff Notice Boards Intranet Equality Impact Assessment Stage 1 Assessment undertaken – no issues identified Date of Issue: July 2020 Next Review: July 2022 Version: 7 Contents DOCUMENT INFORMATION ............................................................................................................................. 2 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 DUTIES ................................................................................................................................................. 3 3.0 TRAINING STRATEGY .......................................................................................................................