Litigating Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alcohol and Alcohol Safetyi a Curriculummanqal for Senior High Level

pocoiENT -RESUME CG,011 580' ED.1.41 733 - AUTHOR Finn, Peter; Platt,,Judith-' , TITLE .Alcohol and Alcohol Safetyi A CurriculumManqal for Senior High Level. Volume II,A Teacher's Acfi..yities .. / . Guide. INSTITUTION Abt AsSociates, Inc.Cambiidge, Mass. SPO_RS AGENCY National Highway Traffic SafetyAdministration (Dq!, :Washington, D. C.; National Inst. onAlcohol'Abuse and Alcoholism (DHEW/PHS), Rockville, Md. - REPORT NO DOT-HS-800-70E 'PUB DATE Sep 72 . CONTRACT HSM-42-71-77 --- NOTE 500p.; For .Volume I, see ED672 383 AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of,Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washingto.C.. 20402 , EDRS PRICE ". MF-7$1-.00 HC-$26.11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alcohol Education; Alcoholism; *Drinking; Instructional Materials;-Interpersonal Competence; , , Laws; Lesson Tlans;.SecondaryEducation; *Senior High Schools; *Social *Attitudes.; *Social Behavior; Teaching Guides. a ABSTRACT ma3/41ual 'on Alcohol, and Alcohol Saf'ety . This curriculum is designed, .as ateacher's guidefor seniot high, level students. The topics it covers are,:(1) safety;.(2) attitudes towardalcohol'gnd reasons people drink.; (3) physical and behavioral effects.; (4) ' alcohol industty;(5) interpersonalsituations;(6) laws and customs;.. and (7),problem drinking andalcoholism. Each topic is divided into a number of activities. Each activityis,a self-contained learning -experience which requires varying numbersof class periods, and: focuses On one or More objectives.The particulaf skills developed by'' the &ctivity, as well as methods forevaluating it, are provided. ' ACtivities are also organized by teaChingmethod: art, audiovisual, debates., discussion, drama, independentstudy, 4ctures, 'reading, science"and, writing. (BP) . * * Documents 'acquired byERIC.incrude many informal unpublished * materials not available, fromother sources. ERIC makes'everY effort * * to obtain the best copyavailable. -

Legal and Institutional Aspects of Fisheries Management And

Indian Ocean Programme IOP/TFJCH/79/30 Teohnioal Report No. 30 (re~trioted) LEGAL AND INST!f.rtJTIONAL ASPFJCTS OF F'ISHERIES MANAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT IN 'I'ffE EXCWSIVE FJCONOMIC ZONE OF THE RTfillUBLIC OF SEYCHELLJl-:S by Michel Savini with the assistance of Barry Hart Dubner Conaultants to the Indian Ooean Programme Under the Direction of the FAO Legislation Branch FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNI'l'.liID NATIONS UNITJ!ID NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Rome, 1979 ii employed and the preBenh:Hon of ·bhiu publication do not imply the erp1'e1uiion of rmy opinion wahower on the plil:rt of ·the Food and 11,gt'ioulture Org&U.Htion of the Uni't;ml Me/Gioi::m 01:m.00rning th@ legal ErtatWJ of rmy uouil'h'y u 'H.1r1'i ·t ory 1 oi ty or area or of it Iii ~•u'Ghori ti4'.HJ 1 or o@n00l':ning the dslimi tat ion of H&i f:t'otrtiei's ©1' b•'ru!lda:daB. Savini, M. & BoHo Dubner ( 1979) .'l'u()h0He1~~.I.122:~5~:1l .. oc~n_E!.'~arllll'1e, (3): 94 P• L8gl1i.and.. irwtitutional aspecj;s of fisheries awl developm~nt in 'Ghe lllxolusive ~"oonowic: zonc3 of ·tho('J Rapublio of Seyohelle<1 Irrte:f·national agreements. Fishery "t'(e u;u1 nt ions" Fishery· management. Fishery development. Fishery· organizationse St'lyclrnlles 111 11'~ oop·,r,;•igrrt i10. 'Ghis book ilB veia·ted in thei Food and Agricmltu.re Organization of the Uni'la:nl Natio111t1. '.l'he book no·\ l)s reproduoed9 in ~In.oh or in pe~rl 1 by rmy method or wi'tlrntrt written from the oopy:t'ight hold.er. -

Moving Forward

Moving Forward FY2012 ANNUAL REPORT The Trevor Project is the leading national organization providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning young people under 24. Every day, The Trevor Project saves young lives through its free and confidential lifeline and instant messaging services, in-school workshops, educational materials, online resources and advocacy. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Executive and Board Message 4 Trevor Timeline: Fiscal Year 2012 5 Spotlights 9 Program Introduction Message 10 Trevor’s Programs 14 Donor Report 18 Trevor Board of Directors and Staff 19 Financial Report EXECUTIVE AND 2/3 | Annual Report FY2012 | MOVING FORWARD BOARD MESSAGE Dea r Friends, Thanks to your unwavering support over this past year, The Trevor Project has moved forward and served more lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) youth than ever before while adding valuable staff members, embracing new executive and Board leadership, and extending Trevor’s reach to new cities nationwide. This year has been full of change, growth, and progress. Our call reports, chat logs, and digital services make it very clear that The Trevor Project is still urgently needed. We saw one of the largest membership increases on TrevorSpace since the program’s inception in 2008 and we watched the number of calls to the Trevor Lifeline surpass 35,000 – nearly 4,000 more than last year. We also expanded the first nationally available chat service specifically for LGBTQ youth in need of support. While we sincerely wish that the need for Trevor’s services would diminish, we are truly grateful to be present to fulfill the needs of young LGBTQ people in crisis. -

Mershon Events in This Issue Mershon Events Wednesday, February 7, 2018

ABOUT US RESEARCH NEWS EVENTS GRANTS PEOPLE CONTACT February 6, 2018 Mershon Events In This Issue Mershon Events Wednesday, February 7, 2018 Mershon News Amr al-Azm, Alam Payind, Richard Herrmann Other Events "Symposium on Syria and Afghanistan: Part II" 6 p.m., 120 Mershon Center, 1501 Neil Ave. Other News Co-sponsored by Middle East Studies Cent er Soviets occupied Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989 to Congratulations prevent the country from collapsing. Currently Russia is treating Syria as a client state in similar Dorothy Noyes ways. Afghanistan remains a struggling democracy, Professor of English and often falling into "failed state" category. The Syrian Comparative Studies state is almost nonexistent in terms of functional central institutions. This symposium will dig deeper into the two countries' situations, answering such In December 2017 Noyes questions as: What are the similarities and visited the Institute of differences with regard to the relationship with Chinese Intangible Cultural Russia? What role do regional rivalries (Iran and Heritage at Sun Yat-sen Saudi Arabia) or intervention (Turkey) play? The University, Guangzhou, as panel features Amr al-Azm (left), associate part of a delegation from professor of Middle East history and anthropology at Shawnee State the American Folklore University; Alam Payind, director of the Middle East Studies Center at Ohio Society, which is State University; and Richard Herrmann, professor and chair, Department celebrating the 10th year of of Political Science. Read more and register its collaboration with the Folklore Society of China. She presented a paper, Monday, February 12, 2018 "The Ethics of Tradition: Responsibility and Possibility," at the Lori Fisler Damrosch International Seminar on "War, Constitutionalism, and International Law: A (Selective) Ethics and Intangible Comparative Study" Cultural Heritage. -

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: a Finding Tool

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: A Finding Tool Denise Monbarren August 2021 Box 1 #GIVING TUESDAY Correspondence [about] #GIVINGWOODAY X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See also Oversized location #J20 Flyers, Pamphlets #METOO X-Refs. #ONEWOO X-Refs #SCHOLARSTRIKE Correspondence [about] #WAYNECOUNTYFAIRFORALL Clippings [about] #WOOGIVING DAY X-Refs. #WOOSTERHOMEFORALL Correspondence [about] #WOOTALKS X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location A. H. GOULD COLLECTION OF NAVAJO WEAVINGS X-Refs. A. L. I. C. E. (ALERT LOCKDOWN INFORM COUNTER EVACUATE) X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ABATE, GREG X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location ABBEY, PAUL X-Refs. ABDO, JIM X-Refs. ABDUL-JABBAR, KAREEM X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases ABHIRAMI See KUMAR, DIVYA ABLE/ESOL X-Refs. ABLOVATSKI, ELIZA X-Refs. ABM INDUSTRIES X-Refs. ABOLITIONISTS X-Refs. ABORTION X-Refs. ABRAHAM LINCOLN MEMORIAL SCHOLARSHIP See also: TRUSTEES—Kendall, Paul X-Refs. Photographs (Proof sheets) [of] ABRAHAM, NEAL B. X-Refs. ABRAHAM, SPENCER X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets ABRAHAMSON, EDWIN W. X-Refs. ABSMATERIALS X-Refs. Clippings [about] Press Releases Web Pages ABU AWWAD, SHADI X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] ABU-JAMAL, MUMIA X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ABUSROUR, ABDELKATTAH Flyers, Pamphlets ACADEMIC AFFAIRS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND TENURE X-Refs. Statements ACADEMIC PROGRAMMING PLANNING COMMITTEE X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ACADEMIC STANDARDS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC STANDING X-Refs. ACADEMY OF AMERICAN POETRY PRIZE X-Refs. ACADEMY SINGERS X-Refs. ACCESS MEMORY Flyers, Pamphlets ACEY, TAALAM X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ACKLEY, MARTY Flyers, Pamphlets ACLU Flyers, Pamphlets Web Pages ACRES, HENRY Clippings [about] ACT NOW TO STOP WAR AND END RACISM X-Refs. -

Economic Commission for Africa the Beverages

Diatr. LIMITED E/CN.14/INR/125 11 August 1966 Original: ENGLISH ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR AFRICA Sub-regional Meeting on Economic Co-operation in West Africa Niamey, 10 - 22 October 1966 THE BEVERAGES INDUSTRY IN THE WEST AFRICAN SUB-REGION M66-l087 E/CN.l4/INR/125 'I:A.BLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Paragraph I FOREWORD -· HIS'IDRIC-UJ AND GENERAL •••••••••• 1- 7 II GENERAL SURVEY OF B3VERAGE PRODUCTION IN T.HE COUNTRIES OF Tl:iE Sul>- REGION •• , •••••••••••••• 8- 35 III DEMAND AND DISTRIBU'.PION OF SOFT DRINKS, BEER A1"'D OTHER ll.L)OROi..IC DRINKS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 36 - 54 IV CONSUMPTION PNf''l;.f.J_d.NS n; s:::=E SUB-REGION COMPARED W:L'd '.LEOS~ UJ:' SOME bEL:dlCTED COUN- :rR.IES • •••... (!! •••••• <: • • • • • • • • • II ... " .......... Ill • 55 - 59 V FUTURE DEMAND FOR BEVERAGES IN THE SUB- REGION , •. t- £ "" .......... (! • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 60 - 80 VI MANUFACTLJRINJ CAPACITY: PRESENT STRUCTURE- FUTURE PROSPECTS •••••• ~.................... 81 - 87 VII CREATION OF' ADDITIONAL MANUFACTURING CAPACI TIES - IlfVES'TI-WJ.Irll"J - GROSS OU'TI?UT - VALUE """~Q'•eo••••••••••••••••• 88 - 113 BIBLIOGRAPHY E/CN.l4/INR/125 CHAPTER I FOREVIORD - HIS'IDRICAL AN.D GENERAL Foreword 1. Two main groups of drinks are generally described as beverages. The first group, non-alcoholic beverages, includes mineral water, aerated waters, lemonades and flavoured waters. The other group, alcoholic beverages; includes wine, cider, beer and distilled alcoholic beverages. L. !hie paper will deal with non-alcoholic beverages in general; the latter group will be divided and beer will be treated separately from other alcoholic beverages. 3. It is difficult to obtain data on beverages; for example, to a great extent, the volume of production, raw materials required, value added and labour force are to a great extent not available. -

The Market of Soft Drinks in Russia and the Russian Far East

The Market of Soft Drinks in Russia and the Russian Far East Market Structure The market of non-alcoholic beverages is currently one of the most attractive for investors. It is characterized by quick payback periods and high profitability. The market of soft drinks in Russia includes the following main groups of drinks: juices, bottled water, carbonated drinks (soda). The bottled water and carbonated drinks account for approximately 67% of all sales. The fruit and vegetable juices take about 12% of soft drinks market. The other drinks occupy 21% of the market. Recently, the popularity of such drinks like cold tea or kvass (Russian national drink https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kvass) highly increased. Regarding the bottled water it is necessary to clarify that a clear distinction should be made between drinking water and mineral water. In Russia the mineral water is divided into healing, table and universal. According to the Russian Union of Soft Drinks Producers (http://www.softdrinks.ru) the share of natural drinking water in the Russian market of bottled water amounts to about 42%. The share of healing mineral water is 8%, the table mineral water equals 34% and the share of universal sparkling mineral water is 16%. However, those categories are vague and very often one may encounter the word “mineral” on the label of bottled water that does not fit into the definition in the least. Some manufacturers believe the word to create positive associations by consumers, thus being more profitable from a marketing perspective. 1 Consumption and production According to the Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (http://www.gks.ru) in 2016 every Russian consumed 93.7 liters of non-alcoholic beverages. -

Mens Rea at the International Criminal Court

Mens Rea at the International Criminal Court <UN> International Criminal Law Series Series Editor M. Cherif Bassiouni (USA/Egypt) Distinguished Research Professor of Law Emeritus, President Emeritus, International Human Rights Law Institute, DePaul University College of Law; Honorary President, International Institute of Higher Studies in Criminal Sciences; Honorary President, Association Internationale de Droit Pénal Kai Ambos (Germany), Judge, André Klip (The Netherlands), Ulrich Sieber (Germany), District Court, Göttingen; Professor of Law, Department of Professor of Criminal Law, Professor of Law and Head, Criminal Law and Criminology, Director, Max Plank Institute Department for Foreign and Faculty of Law, Maastricht University for Foreign and International International Criminal Law, Erkki Kourula (Finland), Former Criminal Law, University of Georg August Universität Judge and President of the Freiburg Mahnoush Arsanjani (Iran), Appeals Division, International Göran Sluiter (The Netherlands), Member, Institut de Droit Criminal Court Professor of Law, Department International; former Director, Motoo Noguchi (Japan), Legal of Criminal Law and Criminal Codification Division, United Adviser, Ministry of Justice of Japan; Procedure, Faculty of Law, Nations Office of Legal Affairs Visiting Professor of Law, University University of Amsterdam Mohamed Chande Othman of Tokyo; former International Otto Triffterer (Austria), (Tanzania), Chief Justice, Judge, Supreme Court Chamber, Professor of International Court of Appeal of Tanzania Extraordinary -

From Repression to Revolution International Criminal Law Series Editorial Board Series Editor M

Libya: From Repression to Revolution International Criminal Law Series Editorial Board Series Editor M. Cherif Bassiouni (USA/EGYPT) Distinguished Research Professor of Law Emeritus, President Emeritus, International Human Rights Law Institute, DePaul University College of Law; President, International Institute of Higher Studies in Criminal Sciences; Honorary President, Association Internationale de Droit Pénal; Chicago, USA Kai Ambos (Germany) Philippe Kirsch (Belgium/Canada) Michael Scharf (USA) Judge, District Court, Göttingen; Ad hoc Judge, International Court of John Deaver Drinko-Baker & Professor of Law and Head, Justice; former President, International Hostetlier Professor of Law, Director, Department for Foreign and Criminal Court; Ambassador (Ret.) Frederick K. Cox International International Criminal Law, Georg and former Legal Advisor, Ministry of Law Center, Case Western Reserve August Universität Foreign Affairs of Canada University School of Law Mahnoush Arsanjani (Iran) André Klip (The Netherlands) Ulrich Sieber (Germany) Member, Institut de Droit Professor of Law, Department of Professor of Criminal Law, Director, International; former Director, Criminal Law and Criminology, Faculty Max Plank Institute for Foreign Codification Division, United of Law, Maastricht University and International Criminal Law, Nations Office of Legal Affairs Erkki Kourula (Finland) University of Freiburg Mohamed Chande Othman (Tanzania) Judge and President of the Appeals Göran Sluiter (The Netherlands) Chief Justice, Court of Appeal of Division, -

Faculty of Business, Economics and Statistics Our Faculty Strives to Provide an En- Vironment to Conduct Research at the Highest Level of Excellence

Research Achievements 2017 17Faculty of Business, Economics and Statistics Our faculty strives to provide an en- vironment to conduct research at the highest level of excellence. This report documents the research output of our Faculty during the ca- lendar year 2017. In the current ver- sion, we keep it concise and compact as we plan to shift to a new format of a yearly report pretty soon. Therefore, the current report can be seen as an interim report. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Nikolaus Hautsch Dean CONTENT 4 Our Research Themes 6 Publications 16 Editorial Work 19 Externally Funded Research Projects 34 Dissemination of Research BEING 41 Citation Based Ranking INQUISITIVE PAYS OFF Our Research Themes Research at our Faculty is diverse and covers a vast consumers, workers, or management in fact behave. We ground. Our research is subdivided into five broad themes use experimental methods to test when the standard which we briefly describe below. model is adequate. And when we find it is not, we develop behavioural theory to account for human error, fear, greed, and judgemental bias. Such an approach benefits Changing Markets and Institutions research from “behavioural finance” to marketing, personnel, strategy, organisation, and economic Our Research Themes — Figure 1 (CMI) sociology. What is the best way to organise economic activity? And, conversely, how are economic outcomes - in markets, in Management of Resources (MR) an industry, a country or even in the global economy - Changing Markets and Institutions shaped by particular governance structures, institutions Resources are the basic input and thus essential drivers of and policies? For example, how does one design auctions or economic activity. -

Faculty and Students Provide Vital Assistance to UN's Investigation Of

v. 10 no. 1 2018 Case Global The Frederick K. Cox International Law Center Faculty and students provide vital assistance to UN’s investigation of Syrian atrocities Ranked 14th in the nation by U.S. News & World Report by Michael Scharf Co-Dean of the Law School Director of the Cox International Law Center WELCOME [email protected] Based on the annual survey of American international law Second, Case was the first law school in the world to offer an professors, U.S. News & World Report has ranked Case Western International Law MOOC, available at https://www.coursera. Reserve as one of the top international law programs in the org/#course/intlcriminallaw. Over 140,000 students from 137 country for the past dozen years. And National Jurist/PreLaw countries have taken the free online course since it was first Magazine gave our international law program an A+ this year. Our offered on Coursera five years ago. international law program includes the endowed Frederick K. Cox International Law Center (established in 1991), the Canada-U.S. Third, we are one of the few schools that offer students the Law Institute (established in 1977), the War Crimes Research Office opportunity to begin to study international law in the first year of (established in 2002), and the Institute for Global Security Law and law school through our very popular Fundamentals of International Policy (established in 2004). This magazine provides an update on Law course, which is designed specifically to prepare 1L students the projects, events and faculty associated with our international for international law-related summer internships. -

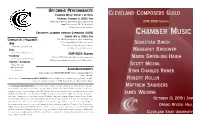

CCG Program October 2019

UPCOMING PERFORMANCES CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY OF OHIO CLEVELAND COMPOSERS GUILD THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 2020 | 7PM Kent State University—Stark (free admission) 2019-2020 SEASON 6000 Frank Avenue NW|North Canton Chamber works by Guild members CREATIVITY: LEARNING THROUGH EXPERIENCE XXVIII CHAMBER MUSIC SUNDAY, MAY 6, 2020 | 3PM CONTACTUS | FOLLOWUS The Music Settlement (free admission) WEB 11125 Magnolia Drive|University Circle SEBASTIAN BIRCH Young music students perform pieces written CLEVELANDCOMPOSERS.COM specially for them by Guild members. EMAIL MARGARET BROUWER [email protected] 2019-2020 SEASON FACEBOOK Watch CLEVELANDCOMPOSERS.COM for news about MARGI GRIEBLING-HAIGH CLEVELAND COMPOSERS GUILD Additional upcoming performances and collaborations. TWITTER | INSTAGRAM @CLECOMPOSERS SCOTT MICHAL #CLECOMPOSERS #CLENEWMUSIC ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to the BASCOM LITTLE FUND for its continuing support of RYAN CHARLES RAMER these concerts. Please listen to INNOVATIONS! ON WCLV 104.9FM with host Mark Satola, featuring music by Northeast Ohio ROBERT ROLLIN composers, Sunday evenings at 9:00. Supported by the Bascom Little Fund. The CLEVELAND COMPOSERS GUILD is one of the nation’s oldest new music organizations, and has had over 200 com- MATTHEW SAUNDERS poser members over its sixty-year history. Over the past six decades, the CCG has built an enviable record of sup- porting new music, with recordings on the CRI, Crystal, Advent, and Capstone labels, and publication series from Ludwig and Galaxy. There are currently about 40 professional composers in the Guild and each concert features a JAMES WILDING wide range of musical styles. In recent years the Guild has collaborated with the Chamber Music Society of Ohio, Cleveland Opera Theater, the Cleveland Chamber Choir, The Syndicate For The New Arts, Cleveland Ballet, and OCTOBER 13, 2019 | 3PM with various local artists to create multi-disciplinary concerts that engage with the arts in a new way.