Peter Sculthorpe’S Pieces with Stephen Kent (Didjeridu) Is Both One of the Most Unusual and Fulfilling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Sculthorpe’S Pieces with Stephen Kent (Didjeridu) Is Both One of the Most Unusual and Fulfilling

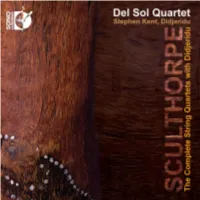

1 CD 1 1 String Quartet No. 12 “From Ubirr” [12:22] String Quartet No. 14 “Quamby” 2 I. Prelude [3:24] 3 II. In the Valley [3:49] 4 III. On High Hills [4:45] 5 IV. At Quamby Bluff [8:00] CD 2 String Quartet No. 16 1 *(6) I. Loneliness [4:10] 2 *(7) II. Anger [3:58] 3 *(8) III. Yearning [5:49] 4 *(9) IV. Trauma [4:18] 5 *(10) V. Freedom [5:30] String Quartet No. 18 6 *(11) I. Prelude [2:04] 7 *(12) II. A Land Singing [4:27] 8 *(13) III. A Dying Land [7:32] 9 *(14) IV. A Lost Land [6:43] 6 *(15) V. Postlude [5:20] Complete Program Time: 82:11 SCULTHORPE The Complete String Quartets with Didjeridu 1 *(Blu-ray™ Tracks) 2 Amongst the amazing artistic collaborations that Del Sol has had in our 22-years of music making, playing Peter Sculthorpe’s pieces with Stephen Kent (didjeridu) is both one of the most unusual and fulfilling. The breathtaking power and beauty of Peter’s music is enhanced by the juxtaposition of these contrasting wooden instruments and traditions - the ones delicately carved by master craftsmen in Europe and the other naturally hollowed out by termites in Australia. Stephen’s artistry envelops us in sonorities that border between the earth and the divine. These sonic waves lift the entire quartet, even changing the role of the cello from harmonic ground to the floor of an airship. We take flight together. We have journeyed to places dark and wondrous during the process of learning these masterworks and hope you will join us there now. -

John Donald Robb Composers' Symposium

The University of New Mexico The College of Fine Arts, Department of Music Presents the Thirty-sixth Annual JOHN DONALD ROBB COMPOSERS’ SYMPOSIUM March 25-28, 2007 Featured Composer: Robert Ashley Curt Cacioppo Paul Lombardi Raven Chacon Brady McElligott Jack Douthett Sam Merciers Neil Haverstick Hyo-shin Na Richard Hermann Patricia Repar Hee Sook Kim Christopher Shultis Richard Krantz John Starrett Thomas Licata Joseph Turrin Peter Lieuwen Scott Wilkinson Artists in Residence Sam Ashley, Jacqueline Humbert Ensembles in Residence Del Sol Quartet: Kate Stenberg, Rick Shinozaki, Charlton Lee, Hannah Addario-Berry PARTCH: John Schneider, David Johnson, Erin Barnes Symposium events are held at the University of New Mexico, Center for the Arts All events are free and open to the public Dr. Christopher Mead, Dean, College of Fine Arts Dr. Steven Block, Chair, Department of Music Composers’ Symposium Staff Dr. Christopher Shultis, Artistic Director Doris Williams, Managing Director; Program Coordinator, John D. Robb Musical Trust Ethan Smith, Graduate Assistant, John D. Robb Musical Trust Victoria Weller, Keller Hall Manager Manny Rettinger, Audio Engineer Cover art: from CD “Foreign Experiences” copyright 1994 photo by Philip Makanna entitled: “Sunset Gas Station.” John Donald Robb John Donald Robb John Donald Robb (1892-1989) led a rich and varied life as an attorney, composer, arts administrator, and ethnomusicologist. He composed an impressive body of work including symphonies, concertos for viola and piano, sonatas, chamber and other instrumental music, choral works, songs, and arrangements of folk songs, two operas, including Little Jo, a musical comedy, Joy Comes to Deadhorse, and more than sixty- five electronic works. -

(630) 815 9363 | [email protected] Delsolquartet.Com Delsolquartet.Com/Joyproject

For Immediate Release 12/4/20 Press contact Jonah Gallagher, Managing Associate, Del Sol Quartet (630) 815 9363 | [email protected] delsolquartet.com delsolquartet.com/joyproject Del Sol Quartet’s Joy Project premieres online, Saturday December 12, 2020 @ 6PM PT (9PM ET). Tickets and registration or https://bit.ly/3gbmmLG Del Sol Quartet has hit the streets with brand-new music composed to spread joy here and now. This is music for sharing — in person and outdoors — short and sweet and unexpected. Music that lets a worker on her lunch break go bananas to a Turkish folk-dance. Music so your neighbors perk up their ears and say hello on their city block. Music so a child can hear the flute-playing tree-spirit who just might live in that pine. Del Sol is performing these specially composed pieces in free concerts at public settings around the Bay Area — parks, schoolyards, open-spaces — where people can enjoy the music while safely practicing social distancing in the open air. “We’re all rediscovering that music can, and should, happen anywhere,” says Del Sol cellist Kathryn Bates. “It’s incredibly satisfying to find this way of connecting with our local communities. Now this online concert allows us to spread our reach and invite everyone, near and far, to a big Zoom party with our favorite composers. Everyone has their own unique experience of joy, from Mark Orton’s playful groove to Jungyoon Wie’s calm meditation or Lukas Ligeti’s polyrhythmic ecstasy.” An all-star team of local and internationally renowned composers quickly stepped up to write music for the Joy Project’s ever-growing setlist. -

Other Minds 20 Festival of New Music March 6, 7And 8, 2015 SFJAZZ Center 201 Franklin Street (At Fell) San Francisco, CA 94102

For Immediate Release October 2014 Further Info: Blaine Todd Director of Communications (415) 934-8134 ext. 301 office (760) 712-8041 mobile Other Minds 20 Festival of New Music March 6, 7and 8, 2015 SFJAZZ Center 201 Franklin Street (at Fell) San Francisco, CA 94102 Other Minds to Celebrate 20th Anniversary Festival with Unprecedented Retrospective Cast U.S. Premiere of Michael Nyman Symphony No. 2 World Premiere of Pauline Oliveros’ Twins Peeking at Koto Tributes to Australian Composer Peter Sculthorpe and American Maverick Lou Harrison Centennial Commemoration of Armenian Genocide Other Minds (OM) in San Francisco announces its 20th anniversary festival of avant- garde music, taking place in San Francisco on Friday March 6th, 7th and 8th, 2015 at the historically distinguished SFJAZZ Center. This annual event is presented in cooperation with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program. For 20 years Other Minds has searched the world over for the most unconventional and inspiring composers of our time. This March, the Other Minds Festival celebrates its 20th edition, and to mark this occasion, for the first time in its history, will present a retrospective cast from festivals past. Among the many highlights this year are the U.S. premiere of Michael Nyman's Symphony No. 2, featuring the San Francisco School of the Arts Youth Orchestra (SOTA) and accompanied by historical clips from Mexican cinema of the 20th Century; the world-premiere performance of Pauline Oliveros' Twins Peeking at Koto, featuring Oliveros and Norwegian accordion virtuoso Frode Haltli and recent Doris Duke Award recipient Miya Masaoka on koto; Masaoka presents her own world premiere, String Quartet No. -

Other Minds Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8wq0984 Online items available Guide to the Other Minds Records Alix Norton, Jay Arms, Madison Heying, Jon Myers, and Kate Dundon University of California, Santa Cruz 2018 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Guide to the Other Minds Records MS.414 1 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Other Minds records Creator: Other Minds (Organization) Identifier/Call Number: MS.414 Physical Description: 399.75 Linear Feet (404 boxes, 15 framed and oversized items) Physical Description: 0.17 GB (3,565 digital files, approximately 550 unprocessed CDs, and approximately 10 unprocessed DVDs) Date (inclusive): 1918-2018 Date (bulk): 1981-2015 Language of Material: English https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f1zk5ftt Access Collection is open for research. Audiovisual media is unavailable until reformatted. Digital files are available in the UCSC Special Collections and Archives reading room. Some files may require reformatting before they can be accessed. Technical limitations may hinder the Library's ability to provide access to some digital files. Access to digital files on original carriers is prohibited; users must request to view access copies. Contact Special Collections and Archives in advance to request access to audiovisual media and digital files. Publication Rights Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. -

Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2017 School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Red Note New Music Festival Music 2017 Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2017 School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/rnf Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Red Note New Music Festival Program, 2017" (2017). Red Note New Music Festival. 4. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/rnf/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Red Note New Music Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CALENDAR OF EVENTS SUNDAY, MARCH 26TH 7 pm, Center for the Performing Arts The Festival opens with a concert featuring the Illinois State University large ensembles. Dr. Glenn Block conducts the ISU Symphony Orchestra in a performance of the winning work in this year’s Composition Competition for Full Orchestra, Melody Eötvös’ The Saqqara Bird. The Symphony will also perform Carl Schimmel’s There Was, and There Was Not with cello soloist Adriana Ransom. The ISU Concert Choir, conducted by Dr. Karyl Carlson, performs the winning piece in the Composition Competition for Chorus, Gaudete by Jorge Andrés Ballasteros. Guest composer Sydney Hodkinson is represented on the remainder of the program by his Symphony No. 10, performed by the ISU Wind Symphony (Dr. Joseph Manfredo, conductor), and his Drawings No. 8 for young string orchestra, which will be performed by students in the ISU String Project. -

Miehigan University Kalamazoo, ~I §Coxencelt)/ @If (C(Q)Mm JP)@~Cerr~}) Iliid~O ~Cmn7 N 2A)J1:Ii@IID©L.Il (C@M:Iifcerrceiid~Ce

Miehigan University Kalamazoo, ~I §coxencelt)/ @if (C(Q)mm JP)@~cerr~}) IlIID~o ~cmn7 N 2a)J1:ii@IID©l.Il (C@m:iifcerrceIID~ce Table of Contents Welcome 2 Schedule ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Registration .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Locations ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................... 5 About the Conference Organizers ......................................................................................................... 7 Featured Ensembles 9 Ensemble Dal Niente............ ...................................................................................................................... 9 Spektral Quartet ......................................................................................................................................... 9 SPLICE Ensemble ....................................................................................................................................... I 0 Coalescence Percussion Duo ................................................................................................................ -

Sample String Quartet Concert Programs

Sample String Quartet Concert Programs Compiled by the Music Entrepreneurship & Career Center, Updated August 2016 We offer these programs, organized in three categories, to help rising musicians develop distinctive programs of their own. Programs marked with asterisks have descriptions included on pages 4-5. 1. Programs Built on a Concept 2. Programs with Newer Repertoire 3. Conventional Programs with a Twist 1. Programs Built on a Concept Del Sol String Quartet Fast Blue Village: Fast Blue Village features works from internationally acclaimed composers reflecting the vibrant sounds and rhythms of diverse cultures from around the world. Jose Evangelista Spanish Garland Lembit Beecher These Memories May Be True Chinary Ung Spiral X: In Memoriam, for amplified string quartet with vocalizations --Intermission-- Mohammed Fairouz The Named Angels Elena Kats Chernin Fast Blue Village Del Sol String Quartet Superflat: Music that blurs the lines of pop art and high art, with works reflecting the influences of classical, jazz and pop idioms. Mads Tolling Commission for Del Sol Quartet Philip Glass String Quartet No. 5 Ben Johnston Revised Standards: “Gershwin, Rogers, Kern” --Intermission-- Ben Johnston Revised Standards: “Set for Billie Holiday” John Cage String Quartet in Four Parts Mason Bates Bagatelles for Amplified String Quartet and Electronica PUBLIQuartet* Hidden Connections Igor Stravinsky Three Pieces for String Quartet Claude Debussy, arr. Norpoth Prelude No. 6, “General Lavine – Eccentric” Claude Debussy String Quartet, Op. 10 Thelonious Monk Green Chimneys Charlie Parker Ah-Leu-Cha Thelonious Monk Off Minor Claude Debussy, arr. Norpoth Golliwogg’s Cakewalk (from Children’s Corner) Amphion String Quartet* Pioneer Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet, Op. -

CONCERT REVIEWS the Fountains and Pines of San Rafael 5 PHILLIP GEORGE

21ST CENTURY MUSIC DECEMBER 2006 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $84.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $36.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $10.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2006 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Typescripts should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors with access to IBM compatible word-processing systems are encouraged to submit a floppy disk, or e-mail, in addition to hard copy. -

THE RIVERS SCHOOL CONSERVATORY the 40Th Annual

THE RIVERS SCHOOL CONSERVATORY The 40th Annual Seminar on Contemporary Music for the Young April 6, 7, & 8, 2018 David J. Tierney, Director, The Rivers School Conservatory Chair, Rivers Performing Arts Department A. Ramón Rivera, Director Emeritus Lindsey Robb, Assistant Director Ethel Farny, Seminar Chair The Rivers School Conservatory 333 Winter Street, Weston, Massachusetts 781-235-6840 www.riversschoolconservatory.org THE SEMINAR ON CONTEMPORARY Sunday, April 8, 2018 MUSIC FOR THE YOUNG 1:00 p.m. SPECIAL PERFORMANCE IN RIVERA HALL: Ensemble of robots perform Phantom of the Opera Reinvented. A multi-media Throughout the weekend, composers offer remarks extravaganza composed by Kurt Coble, featuring solo pianist, Vytas about their music before the performances. Baksys, ensemble of robotic musicians, and the 1925 Silent Era Classic. Friday, April 6, 2018 2:45 p.m. CONCERT IN RIVERA HALL: Music includes works by Grigor Arakelian, Leonard Bernstein, Dan Loschen, and John McDonald. 7:30 p.m. FACULTY RECITAL IN RIVERA HALL: Works of Robert J. Robert Paterson Bradshaw, Whitman Brown, Mikhail Burshtin, Griffin Candey, 4:15 p.m. RECEPTION in the lobby of Bradley Hall for , David Conte, Robert Paterson, and Gwyneth Walker. friends of The Rivers School Conservatory, and performers and their families. 5:00 p.m. FINALE IN RIVERA HALL: Works by Larry Thomas Bell, Allen Saturday, April 7, 2018 Shawn, Dan Shore, Patrice Williamson, and the premiere of the 2018 commissioned work, The Bell for Narrator and Chamber Ensemble by Robert Paterson. This commission is sponsored by Steve 11:00 a.m. WORKSHOP IN RIVERA HALL: Contemporary poets meet con- Snider. -

2014 Festival of Contemporary Music Has Been Endowed in Perpetuity by the Generosity of Dr

TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER an activity of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Andris Nelsons, Ray and Maria Stata Music Director Designate Mark Volpe, Eunice and Julian Cohen Managing Director, endowed in perpetuity Ellen Highstein, Edward H. Linde Tanglewood Music Center Director, endowed by Alan S. Bressler and Edward I. Rudman Tanglewood Music Center Staff Library Anna Doane John Perkel Mary Murray Karen Leopardi Melissa Steinberg TMC Resident Assistants Associate Director for Faculty Orchestra Librarians Ellie Rutledge and Guest Artists Audrey Dunne Residential Office Assistant Michael Nock Head Librarian, Copland Associate Director for Library Audio Department Student Affairs Carlos Garcia Tim Martyn, Gary Wallen Assistant Librarian, Technical Director/Chief Associate Director for Copland Library Engineer Scheduling and Production Douglas McKinnie Production Audio Engineer, Head of Live Sound 2013 SUMMER STAFF John Morin Stage Manager, Seiji Ozawa Charlie Post Chief Audio Engineer, Administrative Hall Benjamin Honeycutt Ozawa Hall Ryland Bennett Assistant Stage Manager, Nicholas Squire Personnel Manager Seiji Ozawa Hall Audio Engineer and Kristie Chan Matt Costa Assistant Radio Engineer Artist Assistant/Driver Mike Martin Joel Watts Sonya Knussen Andrew Maskiell Associate Audio Engineer Office Coordinator Ryan Mix Meghan Ryan Stage Assistants, Seiji Ozawa Piano Programs and Scheduling Hall Assistant Steve Carver Chief Piano Technician Hannah Scott Residential Front Desk Assistant Barbara Renner Peter Lillpopp Chief Piano Technician TMC Residential -

Fast Forward Fund, a Shared Grant of $25,000 to Assist New Music Ensembles and Composers in the Bay Area While We Are All Unable to Perform

For immediate release 5/17/2020 Press contact: Jonah Gallagher, Managing Associate, Del Sol String Quartet (630) 815 9363 [email protected] The Del Sol Performing Arts Organization is proud to announce the Del Sol Fast Forward Fund, a shared grant of $25,000 to assist new music ensembles and composers in the Bay Area while we are all unable to perform. In addition to supporting the Del Sol Quartet, the recipients are the Friction Quartet, The Living Earth Show, Splinter Reeds, ZOFO Duet, Matthew Cmiel, Theresa Wong, and Pamela Z. The Fast Forward Fund is supported by a longtime donor of Del Sol. The fund is looking towards a time when we can all come together and celebrate the return of full audiences to the concert hall for a festive gala, where all recipients will share a stage together. While this grant is unable to support the many other wonderful musicians of our rich and vibrant Bay Area new music community, we are honored to be able to recognize the work and talent of these ensembles and composers. We encourage everyone to support your favorite local artists during this time. The Del Sol Quartet members will be highlighting the musicians receiving awards from the Fast Forward Fund in online interviews over the next couple months. More about Del Sol Quartet Del Sol began as a thought on the night shift at Fermilab. Charlton Lee loved the cutting edge of physics research – always looking for the next discovery, pushing boundaries. But he missed the way music connected people, building community by communicating in ways physics never would.