Seamount Abundances and Abyssal Hill Morphology on the Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Modeling Seafloor Spreading Adapted from a Lesson Developed by San Lorenzo USD Teachers: Julie Ramirez, Veenu Soni, Marilyn Stewart, and Lawrence Yano (2012)

Teacher Instruction Sheet Modeling Seafloor Spreading Adapted from a lesson developed by San Lorenzo USD Teachers: Julie Ramirez, Veenu Soni, Marilyn Stewart, and Lawrence Yano (2012) Teacher Background The process of seafloor spreading created the seafloor of the oceans. For example, in the Atlantic Ocean, North America and South America moved away from Europe and Africa and the resulting crack was filled by mantle material, which cooled and formed new lithosphere. The process continues today. Molten mantle materials continually rise to fill the cracks formed as the plates move slowly apart from each other. This process creates an underwater mountain chain, known as a mid-ocean ridge, along the zone of newly forming seafloor. Molten rock erupts along a mid-ocean ridge, then cools and freezes to become solid rock. The direction of the magnetic field of the Earth at the time the rock cools is "frozen" in place. This happens because magnetic minerals in the molten rock are free to rotate so that they are aligned with the Earth's magnetic field. After the molten rock cools to a solid rock, these minerals can no longer rotate freely. At irregular intervals, averaging about 200-thousand years, the Earth's magnetic field reverses. The end of a compass needle that today points to the north will instead point to the south after the next reversal. The oceanic plates act as a giant tape recorder, preserving in their magnetic minerals the orientation of the magnetic field present at the time of their creation. Geologists call the current orientation "normal" and the opposite orientation "reversed." USGS Teacher Instruction Sheet In the figure above, two plates are moving apart. -

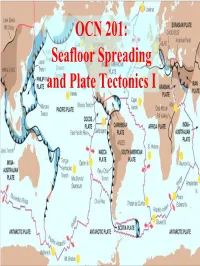

Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

OCN 201: Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics I Revival of Continental Drift Theory • Kiyoo Wadati (1935) speculated that earthquakes and volcanoes may be associated with continental drift. • Hugo Benioff (1940) plotted locations of deep earthquakes at edge of Pacific “Ring of Fire”. • Earthquakes are not randomly distributed but instead coincide with mid-ocean ridge system. • Evidence of polar wandering. Revival of Continental Drift Theory Wegener’s theory was revived in the 1950’s based on paleomagnetic evidence for “Polar Wandering”. Earth’s Magnetic Field Earth’s magnetic field simulates a bar magnet, but it is caused by A bar magnet with Fe filings convection of liquid Fe in Earth’s aligning along the “lines” of the outer core: the Geodynamo. magnetic field A moving electrical conductor induces a magnetic field. Earth’s magnetic field is toroidal, or “donut-shaped”. A freely moving magnet lies horizontal at the equator, vertical at the poles, and points toward the “North” pole. Paleomagnetism in Rocks • Magnetic minerals (e.g. Magnetite, Fe3 O4 ) in rocks align with Earth’s magnetic field when rocks solidify. • Magnetic alignment is “frozen in” and retained if rock is not subsequently heated. • Can use paleomagnetism of ancient rocks to determine: --direction and polarity of magnetic field --paleolatitude of rock --apparent position of N and S magnetic poles. Apparent Polar Wander Paths • Geomagnetic poles 200 had apparently 200 100 “wandered” 100 systematically with time. • Rocks from different continents gave different paths! Divergence increased with age of rocks. 200 100 Apparent Polar Wander Paths 200 200 100 100 Magnetic poles have never been more the 20o from geographic poles of rotation; rest of apparent wander results from motion of continents! For a magnetic compass, the red end of the needle points to: A. -

Seafloor Spreading and Subduction Zones

Name: ___________________________________________ Period: __________ Date: __________________ Seafloor Spreading and Subduction Zones Directions: The diagram on the reverse side depicts an area of the ocean floor where different plates are shifting due to plate tectonics. Begin by labeling the parts (draw an arrow to indicate which feature you mean). Then answer the questions below. You may use your book and whatever notes you have. I. Label the following parts: 2 oceanic plates 2 trenches 1 continental plate mid-ocean ridge 1 oceanic/continental plate transform fault (intersecting the ridge) use brackets mountains (on land) rising magma (in 2 places) island arc II. Further Analysis: 1) Identify the plate boundaries by placing a big letter “D” above the divergent boundary and placing a “C” above each convergent boundary. (Each letter should go in the dotted box.) 2) What process is taking place along the ridge? _______________________________ What process is taking place at the trenches? _______________________________ 3) During subduction, a(n) _________________ plate will sink beneath the continental plate. 4) What causes one plate to sink while another floats? 5) Using a green colored pencil, shade in the area where the youngest ocean rocks would be found with regard to seafloor spreading. Then, in blue, shade in the area of oldest ocean rock. Which of these areas (green or blue) would have the thickest sediment sitting on top of it, AND why? 6) Using a red colored pencil, color in 2 areas of lithosphere where you would find melting rock. What happens to the melted rock, and what landforms does it produce? 7) On your diagram, draw circular arrows to show the circulation of the magma beneath the mid-ocean ridge. -

OCN 201 Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics Question

9/6/2018 OCN 201 Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics Question What was wrong from Wegener’s theory of continental drift? A. The continents were once all connected in a single supercontinent B. The continents slide over ocean floor C. The continents are still moving today D. All of them are correct 1 9/6/2018 Tectonics theories Tectonics: a branch of geology that deals with the major structural (or deformational) features of the Earth and their origin, relationships, and history Late 19th century • Shrinking Earth theory: mountain ranges formed from the contraction and cooling of Earth’s surface • Expansion of the Earth due to heating: to explain why continents are broken up Vertical motion 20th century A new way of thinking about the Earth! • Continental drift theory • Seafloor spreading theory Horizontal motion • Plate tectonics theory Earth’s Magnetic Field A bar magnet with Fe Earth’s magnetic field simulates filings aligning along a bar magnet, but is caused by the “lines” of the convection of Fe in the outer magnetic field core: the Geodynamo… 2 9/6/2018 Earth’s Magnetic Field • Earth’s magnetic field is Dip angle = 90 toroidal, or “donut-shaped” • A freely moving magnet lies horizontal at the equator, vertical at the poles, and points toward the “North” pole • Magnetic inclination: angle between the magnet and Earth’s surface • By measuring the inclination Dip angle = 0 and the angle to the magnetic pole, one can tell position on the Earth relative to the magnetic poles Paleomagnetism • Igneous rock contains magnetic minerals, -

Lesson Outline for Teaching

Lesson Outline for Teaching Lesson 2: Development of a Theory A. Mapping the Ocean Floor 1. Scientists mapped the depth of the ocean floor using a device called a(n) echo sounder. 2. In the middle of the oceans are large mountain ranges called mid-ocean ridges. a. Existence of these mountain ranges was confirmed through echo-sounder research. b. These underwater mountain ranges are much longer than mountain ranges on land. B. Seafloor Spreading 1. Seafloor spreading occurs when new oceanic crust forms at a mid-ocean ridge and old crust moves away from the ridge. a. Molten rock, or magma, rises from the mantle through cracks in the crust. It erupts as lava from volcanic vents along the mid-ocean ridge. b. The molten rock cools and becomes basalt, the rock that forms the oceanic crust. c. New oceanic crust forms along a mid-ocean ridge, and older crust moves away from the ridge. 2. The topography of the seafloor includes the abyssal plain and rugged mountains. a. The rugged mountains that make up the mid-ocean ridge can form in different ways. One way is through large amounts of lava erupting from the center of the Companies, Inc. The McGraw-Hill of a division © Glencoe/McGraw-Hill, Copyright ridge, cooling, and building up around the ridge. Another way is through upward-moving magma pushing on the crust above it, causing it to crack and form jagged, angular mountains on the seafloor. b. Eventually, sediment forms on top of the oldest oceanic crust, making a smooth seafloor called the abyssal plain. -

Drilling the Crust at Mid-Ocean Ridges

or collective redistirbution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of Th e Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or Th eOceanography PO Box 1931, Rockville, USA.Society, MD 20849-1931, or e to: [email protected] Oceanography correspondence all Society. Send of Th approval portionthe ofwith any articlepermitted only photocopy by is of machine, reposting, this means or collective or other redistirbution articleis has been published in Th SPECIAL ISSUE FEATURE Oceanography Drilling the Crust Threproduction, Republication, systemmatic research. for this and teaching article copy to use in reserved. e is rights granted All OceanographyPermission Society. by 2007 eCopyright Oceanography Society. journal of Th 20, Number 1, a quarterly , Volume at Mid-Ocean Ridges An “in Depth” perspective BY BENOÎT ILDEFONSE, PETER A. RONA, AND DONNA BLACKMAN In April 1961, 13.5 m of basalts were drilled off Guadalupe In the early 1970s, almost 15 years after the fi rst Mohole Island about 240 km west of Mexico’s Baja California, to- attempt, attendees of a Penrose fi eld conference (Confer- gether with a few hundred meters of Miocene sediments, in ence Participants, 1972) formulated the concept of a layered about 3500 m of water. This fi rst-time exploit, reported by oceanic crust composed of lavas, underlain by sheeted dikes, John Steinbeck for Life magazine, aimed to be the test phase then gabbros (corresponding to the seismic layers 2A, 2B, for the considerably more ambitious Mohole project, whose and 3, respectively), which themselves overlay mantle perido- objective was to drill through the oceanic crust down to tites. -

The Propagation of Seafloor Spreading in the Southwestern Subbasin, South China Sea

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Article Progress of Projects Supported by NSFC August 2012 Vol.57 No.24: 31823191 SPECIAL TOPIC: Deep Sea Processes and Evolution of the South China Sea doi: 10.1007/s11434-012-5329-2 SPECIAL TOPICS: The propagation of seafloor spreading in the southwestern subbasin, South China Sea LI JiaBiao1,2*, DING WeiWei1,2, WU ZiYin1,2, ZHANG Jie1,2 & DONG ChongZhi1,2 1 Second Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, Hangzhou 310012, China; 2 Key Laboratory of Submarine Geosciences, State Oceanography Administration, Hangzhou 310012, China Received November 20, 2011; accepted April 28, 2012 On the basis of the summary of basic characteristics of propagation, the dynamic model of the tectonic evolution in the South- western Subbasin (SWSB), South China Sea (SCS), has been established through high resolution multi-beam swatch bathymetry and multi-channel seismic profiles, combined with magnetic anomaly analysis. Spreading propagates from NE to SW and shows a transition from steady seafloor spreading, to initial seafloor spreading, and to continental rifting in the southwest end. The spread- ing in SWSB (SCS) is tectonic dominated, with a series of phenomena of inhomogeneous tectonics and sedimentation. Southwestern Subbasin, South China Sea, propagation of seafloor spreading, morphotectonics, tectonic divisions, dynamic mechanism Citation: Li J B, Ding W W, Wu Z Y, et al. The propagation of seafloor spreading in the southwestern subbasin, South China Sea. Chin Sci Bull, 2012, 57: 31823191, doi: 10.1007/s11434-012-5329-2 Recent studies on continental rifting and oceanic spreading Mid-Atlantic Ridge (MAR) [9], but there is no evidence for point out that not all the rifting and spreading occur syn- propagating spreading at ultra-slow spreading mid-ocean chronously along strike [1], and propagating spreading of ridges (e.g. -

Seafloor Spreading

www.ck12.org Chapter 1. Seafloor Spreading CHAPTER 1 Seafloor Spreading Lesson Objectives • Describe the main features of the seafloor. • Explain what seafloor magnetism tells scientists about the seafloor. • Describe the process of seafloor spreading. Vocabulary • abyssal plains • echo sounder • seafloor spreading • trench Introduction World War II gave scientists the tools to find the mechanism for continental drift that had eluded Wegener. Maps and other data gathered during the war allowed scientists to develop the seafloor spreading hypothesis. This hypothesis traces oceanic crust from its origin at a mid-ocean ridge to its destruction at a deep sea trench and is the mechanism for continental drift. Seafloor Bathymetry During World War II, battleships and submarines carried echo sounders to locate enemy submarines ( Figure 1.1). Echo sounders produce sound waves that travel outward in all directions, bounce off the nearest object, and then return to the ship. By knowing the speed of sound in seawater, scientists calculate the distance to the object based on the time it takes for the wave to make a round-trip. During the war, most of the sound waves ricocheted off the ocean bottom. This animation shows how sound waves are used to create pictures of the sea floor and ocean crust: http://earthguid e.ucsd.edu/eoc/teachers/t_tectonics/p_sonar.html . After the war, scientists pieced together the ocean depths to produce bathymetric maps, which reveal the features of the ocean floor as if the water were taken away. Even scientist were amazed that the seafloor was not completely flat ( Figure 1.2). The major features of the ocean basins and their colors on the map in Figure 1.2 include: • mid-ocean ridges: rise up high above the deep seafloor as a long chain of mountains; e.g. -

Plate Tectonics, Seafloor Spreading, and Continental Drift: an Lntroduction1 Rhe Method of Multiple PETE R J

plating the logic and r work." A definitive ::al considerations re s of plate tectonics re- Plate Tectonics, Seafloor Spreading, and Continental Drift: an lntroduction1 rhe method of multiple PETE R J . WYlllE' .ce (old ser.), v. 15, p. ir. Geology, v. 5, p. 837- Abstract The present ruling theory of geote ctonics that the new global tectonics may indeed be v. 31, p. 155-165; 1965, commonly known os the " new globol tectonics'·-includes what Holl is Hedberg in 1970 called "the answer l. the concepts of plote tecto nics, seofloor spreoding, con o a grammar of biology: t inental drift, and polor wondering. Recent seismic oclivily to a maiden's prayer." However, it is time for defines the positions ond relative movements of rigid litho geologists to reflect and consider the evidence ite tectonics in geologic sphere plates. The ge o magnetic time scale for polarity for and against this ruling theory, rather than 107- 11 3. reversals seems lo be calibrated lo about 4 m.y. ago, and to assume that the final word has been handed ologists and paleontology extra polated lo about 80 m.y. ago by correlation of oceonic osal : Jour. P aleontology, mag netic anomalies with reversals a nd seafloor spreading. down. Seafloor spreading and the magnetic anomalies thus indi This review presents a brief introduction to late tectonics: the gco cate the directions and roles of movements of lithosphere 'ace: Science, v. 173, p. the theory, providing a background for the plates during the last 80 m.y. The continents drift with the fo llowing articles, which deal in detail with lithosphere pla tes, and independent paleomagnelic evi lf physical geology : New dence permits location of the relative positio ns of the specific topics. -

SEA-FLOOR SPREADING by the Early 1960S It Was Clear That

SEA-FLOOR SPREADING By the early 1960s it was clear that continental drift occurred - the question was how? The answers came from work being done in the 1950s and 1960s from on the geolog of the sea floor. During this time, precision depths, using echo-sounding to measure the traveltime to the bottom of the ocean, allowed the seafloor to be mapped. Prior to this time, it had been known that there were underwater mountain ranges called "midocean ridges", and very deep regions called trenches, but the overall pattern was unclear. Once a major portion of the ocean floors had been mapped - some striking patterns were clear.(NVE - 47) 1) The midocean ridges often form long continous mountain chains extending for tens of thousands of kilometers. 2) The trenches often do the same. The trenches occur at the edges of coninents (likeW.South America) or near island chains. Tw o other important discoveries were made 3) using the newly established world wide network of seismometers, the distribution of earthquakes was mapped. The vast majority were found to occur alon the midocean ridges and at the trenches (NVE - 54) 4) Heat flowatthe midocean ridges was much higher than in the ocean basins (NVE - 55) The key tothis puzzle was the analysis of the magnetization of the sea floor.Marine geophysicists had been measuring this since the first magnetometers suitable for use at sea were developed in the 1950s. Theydiscovered systematic variations in the amplitude of magnetic anomaly - difference in the earth’sfield due to the magnetized seafloor.Magnetization could be correlated overlarge regions: NVE - 60 The basic idea - which we’ll discuss in detail, is the root of modern theories of plate tectonics.The upper layers of the earth are composed of plates of lithosphere -astrong material above a weaker asthensophese. -

THE OFFICIAL Magazine of the OCEANOGRAPHY SOCIETY

OceThe Officiala MaganZineog of the Oceanographyra Spocietyhy CITATION Fornari, D.J., S.E. Beaulieu, J.F. Holden, L.S. Mullineaux, and M. Tolstoy. 2012. Introduction to the special issue: From RIDGE to Ridge 2000. Oceanography 25(1):12–17, http://dx.doi.org/10.5670/ oceanog.2012.01. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2012.01 COPYRIGHT This article has been published inOceanography , Volume 25, Number 1, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2012 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. USAGE Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. Republication, systematic reproduction, or collective redistribution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or The Oceanography Society, PO Box 1931, Rockville, MD 20849-1931, USA. doWnloaded from http://WWW.tos.org/oceanography OCEANIC SPreAding CenTer ProCesses | Ridge 2000 ProgrAM ReseARCH Introduction to the Special Issue From RIDGE to Ridge 2000 BY DAnieL J. FornAri, STACE E. BEAULieU, JAMes F. HoLden, LAUren S. MULLineAUX, And MAYA ToLSTOY Articles in this special issue of the following quote from H.H. Hess nature of volcanically-driven submarine Oceanography represent a compendium (1962) in his essay on “geopoetry” and hot springs and their attendant chemo- of research that spans the disciplinary commentary on J.H.F. Umbgrove’s synthetically-based animal communities and thematic breadth of the National (1947) comprehensive summary of Earth underscore the fact that the seafloor/ Science Foundation’s Ridge 2000 and ocean history: ridge crest environment represents one Program, as well as its geographic focal The birth of the oceans is a matter of of the current frontiers in the explora- points. -

Chapter 2: Plate Tectonics – Overview Introduction to Oceanography Plate

2/6/2018 Introduction to Oceanography Chapter 2: Plate Tectonics – Overview • Much evidence supports plate tectonics theory. • The plate tectonics model describes features and processes on Earth. • Plate tectonic science has applications to Earth Science studies. • Configuration of land and oceans has changed in the past and will continue to change into the future. Plate Tectonics • Alfred Wegener first proposed in 1912 • Called it “Continental Drift” 1 2/6/2018 Evidence for Continental Drift • Wegener proposed Pangaea – one large continent existed 200 million years ago • Panthalassa – one large ocean • Included the Tethys Sea • Noted puzzle-like fit of modern continents Evidence for Continental Drift • Puzzle-like fit corroborated in 1960s • Sir Edward Bullard used computer models to fit continents. 2 2/6/2018 Evidence for Continental Drift • Matching sequences of rocks and mountain chains • Similar rock types, ages, and structures on different continents Evidence for Continental Drift • Glacial ages and other climate evidence • Evidence of glaciation in now tropical regions • Direction of glacial flow and rock scouring • Plant and animal fossils indicate different climate than today. 3 2/6/2018 Evidence for Continental Drift • Distribution of organisms • Same fossils found on continents that today are widely separated • Modern organisms with similar ancestries Objections to Early Continental Drift Model • 1915 – Wegener published The Origins of Continents and Oceans – Suggested continents plow through ocean basins • Met with hostile