THE LIFE and TIMES of CLAUDE M. LIGHTFOOT a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Volunteer the Volunteer

“...and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” ABRAHAM LINCOLN TheThe VVolunteerolunteer JOURNAL OF THE VETERANS OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN BRIGADE Vol. XXI, No. 4 Fall 1999 MONUMENTAL! Madison Dedicates Memorial ZITROM C to the Volunteers for Liberty ANIEL D By Daniel Czitrom PHOTOS Brilliant sunshine, balmy autumn weather, a magnificent setting Veteran Clarence Kailin at the Madison on Lake Mendota, an enthusiastic crowd of 300 people, and the Memorial dedication reminding spectators presence of nine Lincoln Brigade veterans from around the of the Lincolns’ ongoing commitment to social justice and the importance of pre- nation—all these helped turn the dedication of the nation's sec- serving historical memory. ond memorial to the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, in Madison, More photos page12 Wisconsin on October 31, into a joyful celebration. The two hour program combined elements of a political rally, family reunion, Continued on page 12 Letters to ALBA Sept 11th, 1999 who screwed up when there was still time for a peaceful Comrades, solution—negotiations moderated by Netherland arbiters. I cannot stomach the publication of that fucking I know there are some 60 vets, and maybe you as well, wishy-washy Office resolution on Kosovo, while [some] who will say, “But what about the people getting killed?” boast of the “democratic” vote that endorsed it. What the Good question. What about ‘em? They voted Slobodan in; hell was democratic about the procedure when only that they stood by him and his comrades re Croatia and Bosnia, resolution was put up for voting? No discussion, no they cheered him on in Kosovo . -

October 14, 1976 I Yol.Xll, No

-v who liked our music a lot and some who new album (and other alternative didn't tike it at ¿ll) and after struggling a.lbums). Their letters tell incredible life with the question of oubeach vs. slories, sharing their eicitement, their compromise among ourselves, we fear, their discoveries, their risks. Being decided to do ourthird album on Red- a small company, they figured I might wood, once again. I am telieved that I'm gettheirletters. And I dol There is the not having to deal with the pressure of joy that must match the disappointment the industry but I'm sad when I think of in nof reaching all the women who don't all the people who don't have (oreven have access to an FM radio or altetnative October 14, 1976 I Yol.Xll, No. 34 know about) any optigns. So they watch concerts or womens' records etc. Alice Coopei whip a woman in one of his Right now Redwood Records is only on shocking displays recently performed on the distributing arm for the records and 4. Continental Walk Converges certainly bad news the Billboard Rock Music Awards. songbooks produced to date. We are not Washington / Crace Hedemann for the Portuguese Undet current conditions "energizing- working class, since it means, atbest, capital" can only be accomplishedby How are we going to get options to going to do any new things fot a while. and Murray Rosenblith But we hope that you will continue to the maintenance of the status quo. How- speedups, cutting real'rvages and people? Some people ate working within 6. -

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lvovsky, Anna. 2015. Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463142 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 A dissertation presented by Anna Lvovsky to The Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of American Civilization Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Anna Lvovsky All rights reserved. Advisor: Nancy Cott Anna Lvovsky Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 Abstract This dissertation tracks how urban police tactics against homosexuality participated in the construction, ratification, and dissemination of authoritative public knowledge about gay men in the -

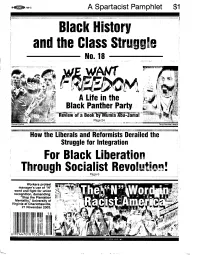

Black History and the Class Struggle

®~759.C A Spartacist Pamphlet $1 Black History i! and the Class Struggle No. 18 Page 24 ~iI~i~·:~:f!!iI'!lIiAI_!Ii!~1_&i 1·li:~'I!l~~.I_ :lIl1!tl!llti:'1!):~"1i:'S:':I'!mf\i,ri£~; : MINt mm:!~~!!)rI!t!!i\i!Ui\}_~ How the Liberals and Reformists Derailed the Struggle for Integration For Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! Page 6 VVorkers protest manager's use of "N" word and fight for union recognition, demanding: "Stop the Plantation Mentality," University of Virginia at Charlottesville, , 21 November 2003. I '0 ;, • ,:;. i"'l' \'~ ,1,';; !r.!1 I I -- - 2 Introduction Mumia Abu-Jamal is a fighter for the dom chronicles Mumia's political devel Cole's article on racism and anti-woman oppressed whose words teach powerful opment and years with the Black Panther bigotry, "For Free Abortion on Demand!" lessons and rouse opposition to the injus Party, as well as the Spartacist League's It was Democrat Clinton who put an "end tices of American capitalism. That's why active role in vying to win the best ele to welfare as we know it." the government seeks to silence him for ments of that generation from black Nearly 150 years since the Civil War ever with the barbaric death penaIty-a nationalism to revolutionary Marxism. crushed the slave system and won the legacy of slavery-,-Qr entombment for life One indication of the rollback of black franchise for black people, a whopping 13 for a crime he did not commit. The frame rights and the absence of militant black percent of black men were barred from up of Mumia Abu-Jamal represents the leadership is the ubiquitous use of the voting in the 2004 presidential election government's fear of the possibility of "N" word today. -

Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers

Winona State University OpenRiver Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers 12-9-1964 Winona Daily News Winona Daily News Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews Recommended Citation Winona Daily News, "Winona Daily News" (1964). Winona Daily News. 543. https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews/543 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Winona City Newspapers at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in Winona Daily News by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (AP) ad CHICAGO Railroermakers and blacksmiths, car-Strike Courts two of its officers; the Interna* The railroads have settled . ' Blo - The s rail traffi c, than withlthe AFL-CIOfo Railway mands for the threeck unions Askea union d na- nation tion's railroads have filed a pe- spokesman said. Employes Department, which "wholly inconsistent with the tion al Association of Machinists men and the firemen and oilers, with 8 of their 11 principal nono- tition in U.S. District Court Judge Joseph Sam Perry had been authorized to bargain recommendations of the Presi- and two of its officers ; and the reached agreement* before the perating unions and all 5 opera* scheduled a hearing today on deadline. seeking to prevent a scheduled the railroad petition filed late for them. dent's Emergency Board . " Sheet Metal Workers' Interna- ting unions within the emerge* strike 10) days before Christmas Tuesday. The carriers sought a tempo- A presidential emergency tional Association and three of The agreements followed ncy's boards recommendations. by three shop unions. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

Volunteer Summer 2000

“...and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” ABRAHAM LINCOLN TheThe VVolunteerolunteer JOURNAL OF THE VETERANS OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN BRIGADE Vol. XXII, No. 3 Summer 2000 Arlo Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Mime Troupe and Garzón Highlight NY Reunion By Trisha Renaud A capacity crowd of 1,000 cheered the introduction of 28 Lincoln Brigade veterans, then EVENSON L cheered again and again in response RIC to the remarks of Judge Baltasar E Garzón from Spain, music from three generations of folk troubadours, and a moving theatrical presentation by HOTO BY P the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Arlo Guthrie, Tao Rodriguez-Seeger, and Pete Seeger The music and speeches focused on similarities between the struggle against fascism 63 years ago in Spain ALBA SUSMAN LECTURE and the more recent struggle against fascism in Chile. The Protection of Human The New York Abraham Lincoln Rights in the International Brigade reunion, held at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, Justice System marked the 63rd anniversary of the brigadistas' arrival in Spain. The by Judge Baltasar Garzón, packed house paid tribute to the 28 page 6 veterans called forward by Moe Fishman to stand before the stage. In attendance were Emilio ERMACK B Cassinello, Spain's Consul-General in New Film by Abe Osheroff, Art In the New York; Anna Perez, representing ICHARD Struggle for Freedom, page 14 Asociación des Amigos de Brigades R Tampa Remembers , page 4 Internationales, a Madrid-based orga- Swiss Monument to IBers, page 5 nization; and James Fernandez, HOTO BY Director of New York University's P George Watt Awards, page 11 continued on page 7 Judge Baltasar Garzón BBaayy AArreeaa By David Smith oe Fishman’s article in the last issue of The Volunteer acted as a catalyst for me to com- MMplete this short report of our activities. -

Cronología De La Guera De España (1936-1939)

Chronology of the War of Spain (1936-1939) (emphasizing the Lincoln Battalion involvement) 1931 13 April: Fall of Spanish monarchy and declaration of Republic. 1933 30 January: Hitler becomes Chancellor in Germany. 1934 12 February: Dollfuss liquidates left-wing oposition in Austria. October: Gen. Franco`s Moorish Troops put down miners`rising in Asturias with considerable brutality. 1935 August: Communist International launches Popular Front policy. 1936 16 February: Conservatives loose Spanish General Elections. Generals Mola and Franco begin conspiracy. 7 March: Nazi troops seize demilitarised Rhineland. 3 May: Popular Front wins French General Elections. 9 May: Fascist Italy annexes Abyssinia. 18 July: Army revolt against Spanish Popular Front government. 25 July: French government forbids arms sales to Republic Spain. 1 September: Franco declared Head (of the Government) of State. 4 September: Largo Caballero becomes Prime Minister of Republican Government; fall of Irún, Basque Country cut off from France. 9 September: Non-Intervention Committee meets in London. 12 October: Formation of International Brigades. 6 November: Republican government leaves Madrid for Valencia. 8 November: XIth International Brigade in action in Madrid. 25 December: The first Americans leave New York on the S.S. Normandie to fight for the Republic. 1937 31 January: Formation of XVth International Brigade, including Lincoln Battalion. 6 February: Battle of Jarama begins. 8 February: Fall of Màlaga. 16 February: Lincoln Battalion first moved to the front lines at Jarama; the first Lincoln casualty, Charles Edwards, on the 17th. 27 February: Lincolns attack Pingarrón Hill (“Suicide Hill”) in Jarama Valley; of the 500 who went over the top, more than 300 were killed or wounded. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

THE PHILOSOPHY of GENERAL EDUCATION and ITS CONTRADICTIONS: the INFLUENCE of HUTCHINS Anne H. Stevens in February 1999, Universi

THE PHILOSOPHY OF GENERAL EDUCATION AND ITS CONTRADICTIONS: THE INFLUENCE OF HUTCHINS Anne H. Stevens In February 1999, University of Chicago president Hugo Sonnen- schein held a meeting to discuss his proposals for changes in un- dergraduate enrollment and course requirements. Hundreds of faculty, graduate students, and undergraduates assembled in pro- test. An alumni organization declared a boycott on contributions until the changes were rescinded. The most frequently cited com- plaint of the protesters was the proposed reduction of the “com- mon core” curriculum. The other major complaint was the proposed increase in the size of the undergraduate population from 3,800 to 4,500 students. Protesters argued that a reduction in re- quired courses would alter the unique character of a Chicago edu- cation: “such changes may spell a dumbing down of undergraduate education, critics say” (Grossman & Jones, 1999). At the meet- ing, a protestor reportedly yelled out, “Long live Hutchins! (Grossman, 1999). Robert Maynard Hutchins, president of the University from 1929–1950, is credited with establishing Chicago’s celebrated core curriculum. In Chicago lore, the name Hutchins symbolizes a “golden age” when requirements were strin- gent, administrators benevolent, and students diligent. Before the proposed changes, the required courses at Chicago amounted to one half of the undergraduate degree. Sonnenschein’s plan, even- tually accepted, would have reduced requirements from twenty- one to eighteen quarter credits by eliminating a one-quarter art or music requirement and by combining the two-quarter calculus re- quirement with the six quarter physical and biological sciences requirement. Even with these reductions, a degree from Chicago would still have involved as much or more general education courses than most schools in the country. -

Judicial Forging of a Political Weapon: the Impact of the Cold War on the Law of Contempt, 27 J

UIC Law Review Volume 27 Issue 1 Article 1 Fall 1993 Judicial Forging of a Political Weapon: The Impact of the Cold War on the Law of Contempt, 27 J. Marshall L. Rev. 3 (1993) Melvin B. Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, International Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, Litigation Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Melvin B. Lewis, Judicial Forging of a Political Weapon: The Impact of the Cold War on the Law of Contempt, 27 J. Marshall L. Rev. 3 (1993) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol27/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUDICIAL FORGING OF A POLITICAL WEAPON: THE IMPACT OF THE COLD WAR ON THE LAW OF CONTEMPT MELVIN B. LEWIS* I. THE ROOTS OF CONTEMPT JURISPRUDENCE Contempt, in its legal sense, is a concept under whose rubric a court or legislative body punishes acts which impede the perform- ance of its official function. The details of its provenance are un- clear. It arose, however, at a time in English history when the powers of the monarch were absolute, and the judicial and parlia- mentary functions were subservient to royal authority. Thus, a dis- respectful act directed toward such a body was defiance of the crown itself, and the contempt power was designed to vindicate royal authority. -

Lawrence Irvin Collection

McLean County Museum of History Lawrence Irvin Collection Processed by Rachael Laing & John P. Elterich Spring 2016 Collection Information: VOLUME OF COLLECTION: Three Boxes COLLECTION DATES: 1939-2002, mostly 1950s-60s RESTRICTIONS: None REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History. ALTERNATIVE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None LOCATION: Archives NOTES: See also—Photographic Collection—People: Irvin; Bloomington Housing Authority Brief History Lawrence E. Irvin, son of Patrick and Mary Irvin, was born May 27, 1911 at Lake Bloomington, Illinois. He attended Trinity High School and Illinois State Normal University. In 1930, he and his two brothers started the Evergreen Beverage Co. (later known as the Pepsi Cola Bottling Company). He took an administrative post as business manager at the Illinois Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Children’s School (ISSCS) in Normal, then was appointed business manager at Illinois State Normal University. During World War II, Irvin served as a Red Cross field director in North Africa and Europe. Upon returning home after the war, he accepted a position as the administrative assistant to Governor Adlai Stevenson II. He held this job from 1949-1953. During this tenure he became close with many politicians, such as Paul Douglas and Paul Simon. He was the Executive Director of the Bloomington Housing Authority from 1953 until he retired in 1985. Irvin was an active participant in Bloomington politics. He was a member of the City Planning and Zoning Board, as well a member of the Bloomington Association of Commerce, the Human Relations Commission, the Citizen’s Community Improvement Committee, and the Urban Planning and Renewal Committee.