Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissenters' Schools, 1660-1820

Dissenters' Schools, 1660-1820. HE contributions of nonconformity to education have seldom been recognized. Even historians of dissent T have rarely done more than mention the academies, and speak of them as though they existed chiefly to train ministers, which was but a very; small part o:f their function, almost incidental. Tbis side of the work, the tecbnical, has again been emphasized lately by Dr. Shaw in the " Cambridge History of Modern Literature," and by Miss Parker in her " Dissenting Academies in England ": it needs tberefore no further mention. A 'brief study of the wider contribution of dissent, charity schools, clay schools, boarding schools, has been laid before the members of our Society. An imperfect skeleton, naming and dating some of the schoolmasters, may be pieced together here. It makes no 'P'r·et·ence to be exhaustive; but it deliberately: excludes tutors who were entirely engaged in the work of pre paring men for the ministry, so as to illustrate the great work clone in general education. It incorporates an analysis of the. I 66 5 returns to the Bishop of Exeter, of IVIurch's history of the Presbyterian and General Baptist Churches in the West, of Nightingale's history of Lancashire Nonconformity (marked N), of Wilson's history of dissenting churches in and near London. The counties of Devon, Lancaste.r, and Middlesex therefore are well represented, and probably an analysis of any county dissenting history would reveal as good work being done in every rplace. A single date marks the closing of the school. Details about many will be found in the Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society, to which references are given. -

EDITORIAL UR April Number Last Year Recorded the Death of Dr

EDITORIAL UR April number last year recorded the death of Dr. _ Nightingale, our President, and M:r. H. A. Muddiman, O our Treasurer. This year we have the sorrowful duty of chronicling the death of the Rev. William Pierce, M.A., for many years ·Secretary of the Society and Dr. Nightingale's successor as President. The Congregational Historical Society has had no more devoted member and officer than M:r. Pierce, and it is difficult to imagine a meeting of the Society without him. He spent his life in the service of the Congregational churches and filled some noted pastorates, including those at New Court, Tollington Park, and Doddridge, Northampton, but he contrived to get through an immense amount of historical research-for many years he had a special table in the North Library of the British Museum. He has left three large volumes as evidence of his industry and his en thusiasm-An Historical Introduction to the Marprektte Tracts, The Marprel,ate Tracts, and John Penry. They are all valuable works, perhaps the reprint of the Tracts especially so, for it not only makes easy of access comparatively rare pamphlets, but it enables us to rebut at once and for always the extraordinary statements made time and again-by writers who obviously have never read the Tracts-to the effect that they are scurri lous, indecent, &c., &c. In this volume Pierce had not much opportunity to show his prejudices, and therefore the volume is his nearest approach to scientific history. The faculty which made him so delightful a companion-the vigour with which he held his views and denounced those who disagreed with him-sometimes led him from the impartiality which should mark the ideal historian : ~ he could damn a bishop he was perfectly happy! But his bias Is always obvious : it never misleads, and it will not prevent his work from living on and proving of service to all students .of Elizabethan religious history. -

Religion & Theology Timeline

Lupton among the Cannons Duckett’s Cross James Buchanan Sir George Fleming, 2nd Baronet c.1651; Headmaster 1657-1662 c.1680 RELIGION & THEOLOGY TIMELINE During Buchanan’s years of office 29 boys Became Canon of Carlisle Cathedral in 1700, 1527 Seats for Sedbergh School went to St. John’s. Became Vicar of Appleby Archdeacon of Carlisle in 1705, Dean in 1727 in 1661 and Rector of Dufton in 1675. and finally Bishop of Carlisle in 1734. He Sedbergh was founded as a Chantry School, meaning Christian worship scholars were allocated in the St. Andrew’s Parish Church. succeeded as 2nd Baronet in 1736. and faith were there from the beginning. The School has produced a steady stream of ministers serving in a wide range of areas including academia and as bishops. The subject of RS continues to flourish at the School with current Upper Sixth pupils intending to pursue study at 1525 Henry Blomeyr Robert Heblethwaite St. John’s College, Cambridge Blessed John Duckett Bishop Thomas Otway John Barwick Lady Betty Hastings Sedbergh School founded as Chantry degree level. Chaplain and Headmaster 1527-1543 c.1544-1585 c.1612-15 OS 1616-1639 c.1630 1682-1739 School. A few scholars studied under a Blomeyr was the Chaplain under whom OS and Headmaster His father was one of the first School Otway was Church of Ireland Bishop of Ossory, he 1631 entered St. John’s College At the age of 23 she Chaplain, initially Henry Blomeyr. a few scholars were gathered from 1525 Believed to have been one of the first pupils at Sedbergh.In Governors and he was believed to be one of became Chaplain to Sir Ralph Hopton and was an active and took holy orders in 1635. -

Candidate Information Brochure

Candidate Information Brochure Interim Estates Manager About Sedbergh School The School Sedbergh School, founded in 1525 by Roger Lupton, Provost of Eton, is an Independent Co-educational Boarding School. The Headmaster is a member of the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference. Set in the spectacular Yorkshire Dales National Park, the School also benefits from fast motorway and rail access to the rest of the UK. The School is a vibrant, demanding and supportive community which encourages pupils and staff to be involved in as broad a range of activities and interests as possible. Art, Drama and Music are especially strong, and the School has a national reputation for Sport. Sedbergh has its own Prep School located approximately five miles away at Casterton. The Principal, Mr A A P Fleck BSc, MA, acts as the “Chief Executive” of both Schools and is supported by a number of senior managers. Mr D J Harrison MA (Cantab) is the Headmaster of Sedbergh Senior School. Mr W R Newman MA is Headmaster of Sedbergh Prep School. The Chief Operating Officer, Peter Marshall, is responsible to the Headmaster and Governors for the management of all the administration and support staff. The COO has responsibility not only for the finances of the School, but also for the extensive land and buildings, maintenance department, grounds & gardens, catering, housekeeping & domestic staff and all other support staff, as well as running the commercial trading arm of the School, Sedbergh School Developments Limited. The Position Sedbergh School is seeking to appoint an Interim Estates Manager for a minimum of 3 months to cover a period of absence of the current incumbent. -

A Retrospect

Rep1·intedjrom the'' EDUCATIONAL RECoRD," June 1915. A RETROSPECT. THE CONTRIBUTION' OF NONCONFORMITY TO EDUCATION UNTIL THE VICTORIAN ERA. A Paper read to the Baptist Historical Society. By W. T. WHITLEY, M.A., LL.D., F.R.HisT.S. Two hundred years ago, "dissenters, in proportion to their numbers, were more vigorous in the course of education than Churchmen were. They not only helped in promoting charity schools ; they had good institutions of their own. In some places the Nonconformist school was the only one to which parents could send their sons." Such is the testimony of Dr. Plnmmer in his History of the English Church in the Eighteenth Century.* It is not surprising that closer studies of the subject have been undertaken in the last five years. In the Cambridge History of Modern Literature, Dr. W. A. Shaw, of thfl Record Office, has appended a list of some Nonconformist Academies to a chapter on the literature of dissent for 1680-1770. Also from the Cambridge lTniversity Press has come a monograph on the same subject, by Miss Parker, lecturf\r in the training college for women teachers at Cherwell Hall, Oxford. These two studies, however, deal with only a part of the su]Jject, the Academies. These are usually con sidered as they tra.ined for the dissenting ministry, and though Miss Parker emphasizes and illnstrates the value of these Academies to general education, neither student professes to expound the activity of Nonconformists in other grades of echool. The purpose of this study is therefore to leave alone the technical and proressional side of the Academies, even to disuse that name, and to indicate .three sides of Nonconformist contributions to general education : Elementary schools, Secondary schools, Literature. -

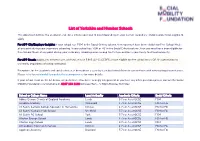

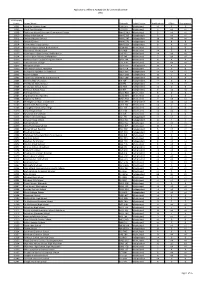

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

Burnley Council Proposed Business Hub

Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (As Amended) Burnley Council Proposed business hub with conference use Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF Parking & Transport Statement VTC (Highway & Transportation Consultancy) Vision House 29 Howick Park Drive Preston PR1 0LU Tel : 01772 740604 Fax : 01772 741670 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.vtc-consultancy.co.uk 20th December 2017 Proposed business hub and conference centre Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF PARKING & TRANSPORT STATEMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ C O N T E N T S 1. Introduction 2. Site Location and Previous Use 3. Existing Highway Network 4. Proposed Conversion Scheme 5. Traffic and Parking impact of the Proposed Conversion 6. Accessibility of the Proposed Development 7. Conclusions and Recommendation References Site Location Plan Appendix 1 – Road Safety Information Appendix 2 – Proposed Conversion Scheme Appendix 3 – Sustainable Transport Information And LCC Accessibility Assessment Photographs Proposed business hub and conference centre Former Burnley Grammar School, School Lane in Burnley BB11 1UF PARKING & TRANSPORT STATEMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction 1.1 This Parking and Transport Statement has been prepared to accompany the planning application for a proposed business hub, with conference facilities, at the former Burnley Grammar School off School Lane in Burnley town centre. The proposed -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

Job 143198 Type

Grade II country house with pool, barn & over 10 acres Broughton Hall, Cartmel, Grange-Over-Sands, Cumbria LA11 7SH Freehold 5 bedrooms • 3 further second floor rooms • 4 bathrooms • 4 reception rooms • Dining kitchen • 2 storey barn • Indoor swimming pool • About 10.8 acres Local information with the broad range of leisure Broughton Hall stands in an activities on offer. The Cumbria elevated setting with a parkland Coastal Way is within reach from view of the idyllic Cartmel valley, your doorstep, via an old bridle about 1.4 miles north of the pathway. There are horse stables village. This historic village is a in Cartmel for riding enthusiasts. gastronomic hub, offering The racecourse has 9 fixtures in everything from two-Michelin the racing calendar from May– starred L’Enclume and its one- August. Grange Fell Golf club is star sister restaurant Rogan & Co. just outside Cartmel, and there to a range of pubs, bars and are four other courses within half cafes, as well as the famous an hour. Village Shop: home of Cartmel There are good local schools in sticky toffee pudding. A Cartmel, and Lancaster Royal convenience store provides most Grammar School is easily day-to-day necessities and there accessible on the train from are supermarkets, an award- Grange-over-Sands station. winning butchers and a bakery in Dallam School is an IB World Grange-over-Sands. School, only a 20-minute drive The village has a wealth of away. Sedbergh School is about leisure attractions, including a 25 miles away. National Hunt Racecourse and speciality shops such as Perfect About this property English and the Simon Rogan This remarkable Grade II listed shop. -

Cumbria County Council Serving the People of Cumbria

Cumbria County Council Resources and Transformation Information Governance Team Lonsdale Building The Courts Carlisle CA3 8NA T: 01228 221234 E: [email protected] E-mail: 10 August 2016 Your reference: Our reference: FOI 2016-0541 Dear FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 2000 - DISCLOSURE The council has completed its search relating to your request for information about school bus/coach contracts, which was received on 18 May 2016. The council does hold information within the definition of your request. Request 1. Details of all school bus/coach contracts that are current at present showing: • At least the start and finish point with route of the individual contracts giving enough detail so as to identify what the contract is. • The amount of pupils carried or seating capacity • Who the contract has been placed with. • The daily/annual rate as appropriate. 2. Details of any bulk purchasing of scholars season tickets/passes • At least the start and finish point of the individual contracts giving enough detail so as to identify what the contract is. • The amount of pupils carried or seating capacity • Who the contract has been placed with. • The daily/annual rate as appropriate. Response Please see attachment for your information. The daily/annual rate is withheld under Section 43(2) of the FOIA, however the details of all spend over £500 per month are available online at: http://www.cumbria.gov.uk/managingyourcouncil/councilspend500/default.asp . All school bus/coach contracts fall into this category (as based on a typical 20 working days per month, this will be £25 per day, and currently we have no routes for buses/coaches that fall below this price threshold). -

2009 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2009 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <4 0 0 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <4 <4 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent 7 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 18 <4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 20 8 8 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 8 4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 5 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <4 0 0 10022 Queensbury Upper School, Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 <4 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 7 <4 <4 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 8 4 4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 15 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 0 0 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 7 6 10033 The School of St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 22 9 9 10035 Dean College of London N7 7QP Independent <4 0 0 10036 The Marist Senior School SL57PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 0 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 <4 <4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 0 0 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames