'Tell Me All About Your New Man': (Re)Constructing Masculinity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Film & Media Studies Hunter College

Department of Film & Media Studies Jeremy S. Levine Hunter College - CUNY 26 Halsey St., Apt. 3 695 Park Ave, Rm. 433 HN Brooklyn, NY 11216 New York, NY 10065 Phone: 978-578-0273 Phone: 212-772-4949 [email protected] Fax: 212-650-3619 jeremyslevine.com EDUCATION M.F.A. Integrated Media Arts, Department of Film & Media Studies, Hunter College, expected May 2020 Thesis Title: The Life of Dan, Thesis Advisor: Kelly Anderson, Distinctions: S&W Scholarship, GPA: 4.0 B.S. Television-Radio: Documentary Studies, Park School of Communications, Ithaca College, 2006 Distinctions: Magna Cum Laude, Park Scholarship EMPLOYMENT Hunter College, 2019 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Film & Media Studies Taught two undergraduate sections of Intro to Media Studies in spring 2019, averaging 6.22 out of 7 in the “overall” category in student evaluations, and teaching two sections of Intro to Media Production for undergraduates in fall 2019. Brooklyn Filmmakers Collective, 2006 – Present Co-Founder, Advisory Board Member Co-founded organization dedicated to nurturing groundbreaking films, generative feedback, and supportive community. Recent member films screened at the NYFF, Sundance, and Viennale, broadcast on Showtime, HBO, and PBS, and received awards from Sundance, Slamdance, and Tribeca. Curators from Criterion, BAM, Vimeo, The Human Rights Watch Film Festival, and Art 21 programmed a series of 10-year BFC screenings at theaters including the Lincoln Center, Alamo, BAM, and Nitehawk. Transient Pictures, 2006 – 2018 Co-Founder, Director, Producer Co-founded and co-executive directed an Emmy award-winning independent production company. Developed company into a $500K gross annual organization. Directed strategic development, secured clients, managed production teams, oversaw finances, and produced original feature films. -

NCA All-Star National Championship Wall of Fame

WALL OF FAME DIVISION YEAR TEAM CITY, STATE L1 Tiny 2019 Cheer Force Arkansas Tiny Talons Conway, AR 2018 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2017 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2016 The Stingray All Stars Grape Marietta, GA 2015 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2014 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2013 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2012 Texas Lonestar Cheer Company Houston, TX 2011 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2010 Texas Lonestar Cheer Company Houston, TX 2009 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Dallas, TX 2008 Woodlands Elite The Woodlands, TX 2007 The Pride Addison, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1.1 Tiny Prep D2 2019 East Texas Twisters Ice Ice Baby Canton, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1.1 Tiny Prep 2019 All-Star Revolution Bullets Webster, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1 Tiny Prep 2018 Liberty Cheer Starlettes Midlothian, TX 2017 Louisiana Rebel All Stars Faith (A) Shreveport, LA Cheer It Up All-Stars Pearls (B) Tahlequah, OK 2016 Texas Legacy Cheer Laredo, TX 2015 Texas Legacy Cheer Laredo, TX 2014 Raider Xtreme Raider Tots Lubbock, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1 Mini 2008 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2007 Odyssey Cheer and Athletics Arlington, TX 2006 Infinity Sports Kemah, -

Inakustik/Music Video Distributors Jazz/Blues Blu-Ray Concert

Inakustik/Music Video Distributors Jazz/Blues Blu-ray Concerts (Autou... http://www.fulvuedrive-in.com/review/8856/Inakustik/Music+Video+Dis... Find Category: Home > Reviews > Jazz > Blues > Pop > Inakustik/Music Video Distributors Jazz/Blues Blu-ray Concerts (Autour Du Blues/Jose Feliciano Band/Stanley Jordan Trio/Mike Stern Band/Yellowjackets: New Morning Paris/Ohne Filter DVD/Lifecycle SACD) Inakustik/Music Video Distributors Jazz/Blues Blu-ray Concert Wave (Autour Du Disc Duplication Blues/Jose Feliciano > The Green Hornet (1940) + Systems Band*/Stanley Jordan The Green Hornet Strikes CD/DVD/BD Again! (1941/VCI DVD Sets) Trio*/Mike Stern Band/Yellowjackets: New Duplicators, > Torchwood – The Complete Printers and Disc Second Season (BBC Blu-ray) Morning Paris [*w/DVD Version]) > The Middleman – The + Yellowjackets In Concert: Wrappers, Complete Series (2008/Shout! Ohne Filter 1994 DVD + Supplies & Advice! www.SummationTechnology.com Factory) Yellowjackets Featuring Mike > Doctor Who – Planet Of The Stern – Lifecycle SA-CD (Heads Dead (2009/BBC Blu-ray) Up Super Audio CD/SACD/2008) > The Spectacular Spider-Man Blu Ray – The Complete First Season Picture: B-/C+ Blu-ray Sound: B (Marvel/Sony Wonder DVD) Download DVD Sound B/B- SA-CD Sound: B- WinDVD ® 9 Plus > Marple – Series Four (2008 – (PCM)/B (2.0 DSD Stereo)/B+ (5.1 2009/Acorn DVD) Blu-ray from Corel DSD) Extras: C- Concerts/Album: ® & Start Using It > The Soloist B- (2009/DreamWorks/Paramount Now! Blu-ray + DVD) www.Corel.com > Super Why – Jack & The Beanstalk and other fairytale The concerts released by Inakustik adventures (PBS Home through Music Video Distributors is the Video/Paramount DVD) longest and most numerous in all of 24 Hours 1-7 DVD > Life On Mars – Series One home video, from the Ohne Filter TV $89 (2006/British TV/Acorn DVD) + series to the New Morning – The Paris Concert series. -

Integrating Video Clips Into the “Legacy Content” of the K–12 Curriculum: TV, Movies, and Youtube in the Classroom

Integrating Video Clips into the “Legacy Content” of the K–12 Curriculum: TV, Movies, and YouTube in the Classroom Ronald A. Berk Disclaimer: This chapter is based on a presentation given at the annual Evaluation Systems Conference in Chicago. Since the content of the October 2008 presentation focused on using videos in the classrooms of the future, this chapter will not be able to capture the flavor and spirit of the actual videos shown. The audience exhibited a range of emotions, from laughter to weeping to laughter to weeping. Unfortunately, this print version will probably only bring about the weeping. Keep a box of tissues nearby. Enjoy. Using videos in teaching is not new. They date back to prehistoric times, when cave instructors used 16 mm projectors to show cave students examples of insurance company marketing commercials in business courses. Now even DVD players are history. So what’s new? There are changes in four areas: (1) the variety of video formats, (2) the ease with which the technology can facilitate their application in the classroom, (3) the number of video techniques a teacher can use, and (4) the research on multimedia learning that provides the theoretical and empirical support for their use as an effective teaching tool. A PC or Mac and a LCD projector with speakers can easily embed video clips for a PowerPoint presentation on virtually any topic. This chapter examines what we know and don’t know about videos and learning. It begins with detailed reviews of the theory and research on videos and the brain and multimedia learning. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Bridget Jones's Legacy

Bridget Jones’s Legacy : Gender and Discourse in Contemporary Literature and Romantic Comedy A daptations Miriam Bross Thesis s ubmitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film Studies (Research) School of Art, Media and American Studies University of East Anglia December 2016 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. A bstract Romantic comedy adaptations based on bestsellers aimed at predominantly female readers have become more frequent in the fifteen years since the publication of Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) and the financial success of its adaptation (Sharon Maguire, 2001). Contemporary popular literature and films created specifically for women have emerged alongside the spread of neoliberalist and postfeminist discourses. This thesis offers a timely examination of bestselling adapted texts, including chick lit novels, a sel f - help book and a memoir, and their romantic comedy adaptations. While some of the books and films have received individual attention in academic writing, they have not been examined together as an interconnected group of texts. This thesis is the first work to cohesively analyse representations of gender in mainstream bestsellers predominantly aimed at female readers and their romantic comedy adaptations published and released between 1996 and 2011. Through a combination of textual analysis and broader d iscursive and contextual analysis, it examines how these popular culture texts adapt and extend themes, characters , narrative style and the plot structure from Bridget Jones’s Diary . -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

9781474452090 Introduction.Pdf

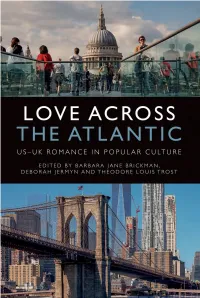

Love Across the Atlantic 6216_Brickman.indd i 30/01/20 12:30 PM 6216_Brickman.indd ii 30/01/20 12:30 PM Love Across the Atlantic US–UK Romance in Popular Culture Edited by Barbara Jane Brickman, Deborah Jermyn and Theodore Louis Trost 6216_Brickman.indd iii 30/01/20 12:30 PM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation Barbara Jane Brickman, Deborah Jermyn and Theodore Louis Trost, 2020 © the chapters their several authors, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5207 6 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5209 0 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5210 6 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 6216_Brickman.indd iv 30/01/20 12:30 PM Contents List of Figures vii Acknowledgements viii The Contributors xii Introduction: Still Crazy After All These Years? The ‘Special Relationship’ in Popular Culture 1 Barbara Jane Brickman, Deborah Jermyn and Theodore Louis Trost Part One ‘[Not] Just a Girl, Standing in Front of a Boy . -

St Catherine's Field Church Hill, Shere, GU5 9HL

St Catherine's Field Church Hill, Shere, GU5 9HL A collection of three exclusive, luxury homes set amongst the magnif icent Surrey hills About Shere A beautifull village set in the Surrey Hills. The village sits astride the river Tillingbourne. Shere is a small picturesque village situated below the North Downs, Shere is mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1087 as Essira and six miles south-west of Guildford and approximately twenty miles mentions the Church of St James church. The cottages in Shere from London. It is regarded by many as the prettiest village in Surrey present a mixture of styles from the 15th to 20th centuries, but the and is certainly the most photographed. The village is much sought central part of the village is fundementally 16th and 17th century, after as a residential location, being within commuting distance of with many timber framed houses. The names of the houses in London and accessible to the M25 motorway. Lower Street indicate the growth of population and increased prosperity in this period, produced by the woollen industry. Set it in the Tillingbourne Valley, Shere has everything a village Lower Street runs alongside the River Tillingbourne to the Ford. should offer. There is a 12th century church, a ford, the famous Here you can see The Old Forge, The Old Prison, Weavers House Shere ducks to feed, two pubs, The White Horse and The William and Wheelwright Cottage. Bray, shops, post office, The Dabbling Duck Tea Room, Kinghams, an award winning restaurant, a doctors surgery and popular primary Shere is surrounded by stunning scenery and close to popular scenic school. -

Schmidt Karen.Pdf (678.5Kb)

FACULTY OF ARTS AND EDUCATION MASTER’S THESIS Programme of study: Spring semester, 2016 Master in Literacy Studies Open Author: Karen Schmidt ………………………………………… (Author’s signature) Supervisor: Dr. Mildrid H.A. Bjerke Thesis title: Chick or Lit: An Investigation of the Chick Lit Genre in Light of Traditional Standards of Literary Value Keywords: No. of pages: 115 Literary value + appendices/other:9 Western Canon Popular fiction Chick Lit Stavanger, 11th May 2016 Postfeminism Abstract The present master’s thesis explores the chick lit genre in light of traditional standards of literary value. The thesis investigates how literary value and quality has been defined through the last couple of centuries, as well as how popular fiction, and chick lit in particular, is evaluated in terms of literary value and quality. The thesis seeks to understand how the popular embrace of genre fiction, like chick lit, relates to the typical critical rejection of such writing. Ultimately, the motivation behind the present thesis is to reach an understanding of why it is necessary to discriminate between good and bad writing, and whether it is possible to discuss literary value and quality without such a binary mode of thinking. The thesis’s first body chapter explores how literary value and quality has been defined in the past. Central works are Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy (1882[1869]) and ‘The Study of Poetry’ (1880), Q.D. Leavis’s Fiction and the Reading Public (1932), F.R. Leavis’s The Great Tradition (1960[1948]) and Culture and Environment (1977[1933]) and Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory (2008[1983]). -

The Holiday Hans Zimmer

The holiday hans zimmer Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The Holiday) . The entire work of Hans Zimmer for this movie was amazing. Hans Zimmer music is so profoundly outstandingly mesmerizing I love Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The. Disclaimer: No copyright infringement intended. The audio content doesn't belong to me I don't make profit. Product description. Composer: Hans ers: Atli �rvarsson; Heitor Teixeira Pereira; Lorne Balfe; Herb Alpert; Imogen Heap; Ryeland Allison. Listen to The Holiday (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) by Hans Zimmer on Deezer. With music streaming on Deezer you can discover more. Stream Hans Zimmer - Maestro - The Holiday Soundtrack by Aya G. El-Sobhi from desktop or your mobile device. Stream Hans Zimmer - Maestro (extended Version) - Soundtrack of "The holiday" by Irene Fouad from desktop or your mobile device. Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The Holiday) Hans Zimmer - Maestro (The Holiday). Repost Like. Stan. Hans Zimmer, Lorne Balfe, Henry Jackman, Atli Örvarsson . something in that movie struck my ears near the end the score sounds a lot like Holiday's Maestro. The Holiday is de originele soundtrack van de film uit met de dezelfde naam, en werd gecomponeerd door Hans Zimmer. Het album werd op 9 januari. Find a Hans Zimmer - The Holiday (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) first pressing or reissue. Complete your Hans Zimmer collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. The Holiday is a American romantic comedy film written, produced and directed by Nancy .. Hans Zimmer also composed and produced the score for The Holiday. Jack Black later spoofed the movie in Be Kind Rewind. According to a Release date: December 8, The Holiday (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack). -

Title Actors Genre Rating Other Imdb Link Step Brothers Will Ferrell, John Comedy Unrated Wide - Includes Special Features: C

Title Actors Genre Rating Other IMDb Link Step Brothers Will Ferrell, John Comedy Unrated wide - Includes special features: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt08382 C. Reilly screen edition commentary, extended version, 83/ alternate scenes, gag reel Tommy Boy Chris Farley, Comedy PG -13 Includes special features: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt01146 David Spade Widescreen version, dolby digital, 94/ English subtitles, interactive menus, scene selection, theatrical trailer Love and Basketball Sanaa Lathan, Drama PG -13 Commentary, 5.1 isolated score, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt01997 Omar Epps Romance deleted scenes, blooper real, audition 25/ tapes, music video, trailer Isolated Incident -Dane Dane Cook Comedy Not rated Bonus features: isolated interview http://www.imdb.com/title/tt14 022 Cook with Dane, 30 premeditated acts 07/ Anchorman: The Will Ferrell Comedy Not Rated Bonus features: Unforgettable http://www.imdb.com/title/tt03574 legend of Ron Romance interviews at the mtv movie awards, 13/ Burgundy (2-copies) ron burgundy’s espn audition, making of anchorman Hoodwinked Glen Close, Anne Animation PG Special features: deleted scenes, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt04435 Hathaway, Xzibit Comedy commentary with the filmmakers, 36/ Crime theatrical trailer Miss Congeniality (2 - Sandra Bullock . Action PG -13 Deluxe edition; special features: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt02123 copies) Michael Caine Comedy sneak peek at miss congeniality 2, 46/ Crime additional scenes, commentaries, documentaries, theatrical trailer Miss Congeniality 2: Sandra Bullock Action PG -13 Includes: additional scenes, theatrical http://www.imdb.com/title/tt03853 Armed and Fabulous Comedy trailer 07/ Crime Shrek 2 Mike Myers, Eddie Animation PG Bonus features: meet puss and boots, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt02981 Murphy, Cameron Adventure commentary, tech of shrek 2, games 48/ Diaz Comedy and activities The Transporter Jason Statham, Action PG - 13 Special features: commentary, http://www.