Mennonites in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winkler Voice 101917.Indd

Automotive Glass Chip Repairs Tinting Farm Equipment Auto Accessories 204-325-8387 150C Foxfi re Trail Winkler, MB (204)325-4012 600 Centennial St., Winkler, MB Winkler Morden VOLUME 8 EDITION 42 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2017 VVLocally ownedoiceoice & operated - Dedicated to serving our communities Fun at the fi rere hall PHOTO BY RICK HIEBERT Teil, Rhylen, and Aliya of Winkler enjoy the vintage fi re truck on display at the Winkler Fire Hall during the department’s annual Fire Preven- tion Week Open House Oct. 11. For more photos, see Pg. 32. news > sports > opinion > community > people > entertainment > events > classifi eds > careers > everything you need to know 2 The Winkler Morden Voice Thursday, October 19, 2017 HOLIDAY Christmas Basics Jingle Pets CHRISTMAS COATS OVERLOCK COLLECTION SERGING THREAD 112 cm wide, 100% 1500m spools. cotton. All Stock. Includes Quiltand $ .85 SALE Collections. 1 % OFF REG $4 EACH 50 REG PRICE Everyday Soft Worsted “SPECIAL PURCHASE” YARN IMPLEMENTS & PREMIER YARN % COLLECTION ACCESSORIES All stock. Includes parfait, 50 All stock. Includes needle serenity, wool naturals, mega tweed and new colours in sets by Susan Bates, Aero REG Home Cotton. OFFPRICE 30% OFF & Tailor. Cable & Ribs Hat REG PRICE Scarf Armwarmer NEW PELLON GRAB’N’GO INTERFACING BOLTS OLFA CUTTING MATS, In 4 styles. LIGHTWEIGHT LIGHTWEIGHT ROTARY CUTTERS & FUSIBLE INTERFACING FLEXI FIRM DOUBLE BLADES All stock. 20”x20 yards. SIDED FUSIBLE $ SALE 20”x10 yards. 11 REG $24.99/EA $ SALE % OFF 43 REG $85.99/EA 50 LIGHTWEIGHT REG PRICE FLEXI FIRM SEW-IN LIGHTWEIGHT FUSIBLE 20”x10 yards. NEEDLE PUNCH/FLEECE $ SALE 45”x10 yards. -

Carte Des Zones Contrôlées Controlled Area

280 RY LAKE 391 MYSTE Nelson House Pukatawagan THOMPSON 6 375 Sherridon Oxford House Northern Manitoba ds River 394 Nord du GMo anitoba 393 Snow Lake Wabowden 392 6 0 25 50 75 100 395 398 FLIN FLON Kilometres/kilomètres Lynn Lake 291 397 Herb Lake 391 Gods Lake 373 South Indian Lake 396 392 10 Bakers Narrows Fox Mine Herb Lake Landing 493 Sherritt Junction 39 Cross Lake 290 39 6 Cranberry Portage Leaf Rapids 280 Gillam 596 374 39 Jenpeg 10 Wekusko Split Lake Simonhouse 280 391 Red Sucker Lake Cormorant Nelson House THOMPSON Wanless 287 6 6 373 Root Lake ST ST 10 WOODLANDS CKWOOD RO ANDREWS CLEMENTS Rossville 322 287 Waasagomach Ladywood 4 Norway House 9 Winnipeg and Area 508 n Hill Argyle 323 8 Garde 323 320 Island Lake WinnBRiOpKEeNHEgAD et ses environs St. Theresa Point 435 SELKIRK 0 5 10 15 20 East Selkirk 283 289 THE PAS 67 212 l Stonewall Kilometres/Kilomètres Cromwel Warren 9A 384 283 509 KELSEY 10 67 204 322 Moose Lake 230 Warren Landing 7 Freshford Tyndall 236 282 6 44 Stony Mountain 410 Lockport Garson ur 220 Beausejo 321 Westray Grosse Isle 321 9 WEST ST ROSSER PAUL 321 27 238 206 6 202 212 8 59 Hazelglen Cedar 204 EAST ST Cooks Creek PAUL 221 409 220 Lac SPRINGFIELD Rosser Birds Hill 213 Hazelridge 221 Winnipeg ST FRANÇOIS 101 XAVIER Oakbank Lake 334 101 60 10 190 Grand Rapids Big Black River 27 HEADINGLEY 207 St. François Xavier Overflowing River CARTIER 425 Dugald Eas 15 Vivian terville Anola 1 Dacotah WINNIPEG Headingley 206 327 241 12 Lake 6 Winnipegosis 427 Red Deer L ake 60 100 Denbeigh Point 334 Ostenfeld 424 Westgate 1 Barrows Powell Na Springstein 100 tional Mills E 3 TACH ONALD Baden MACD 77 MOUNTAIN 483 300 Oak Bluff Pelican Ra Lake pids Grande 2 Pointe 10 207 eviève Mafeking 6 Ste-Gen Lac Winnipeg 334 Lorette 200 59 Dufresne Winnipegosis 405 Bellsite Ile des Chênes 207 3 RITCHOT 330 STE ANNE 247 75 1 La Salle 206 12 Novra St. -

3 a Forgotten Encounter 13 Reorienting the West Reserve 21

Mennonites on the Rails ISSUE NUMBER 39, 2019 3 A Forgotten 13 Reorienting 21 The Railroad Encounter the West Passes by The C.N.R.’s Community Reserve Steinbach Progress Competitions Mennonites and the Ralph Friesen James Urry Railway Hans Werner Contents ISSUE NUMBER 39, 2019 1 Notes from the Editor A JOURNAL OF THE D. F. PLETT HISTORICAL RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. Features EDITOR Aileen Friesen 3 A Forgotten COPY EDITOR Andrea Dyck Encounter DESIGNER Anikó Szabó James Urry PUBLICATION ADDRESS Plett Foundation 13 Reorienting the University of Winnipeg West Reserve 515 Portage Ave Hans Werner Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 2E9 21 The Railroad Passes 3 EDITORIAL SUBMISSIONS by Steinbach Aileen Friesen Ralph Friesen +1 (204) 786 9352 [email protected] SUBSCRIPTIONS AND Research Articles ADDRESS CHANGES Andrea Dyck [email protected] 25 Mennonite Debt in the West Reserve Preservings is published semi-annually. Bruce Wiebe The suggested contribution to assist in covering the considerable costs of preparing this journal is $20.00 per year. 31 The Early Life 31 Cheques should be made out to the of Martin B. Fast D. F. Plett Historical Research Foundation. Katherine Peters Yamada MISSION To inform our readers about the history of 37 Klaas W. Brandt the Mennonites who came to Manitoba in the Dan Dyck 1870s and their descendants, and in particular to promote a respectful understanding and appreciation of the contributions made by so-called Low German-speaking conservative Histories & Reflections Mennonite groups of the Americas. Mennonite-Amish- 43 37 PLETT FOUNDATION Hutterite Migrations BOARD OF DIRECTORS John J. Friesen 2019–2020 Royden Loewen, Chair, Winnipeg, MB John J. -

2018 Population Report

1 Population Statistics 2018 | Southern Health-Santé Sud Published: April 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 3 3 Municipal Amalgamations for 2018 4 2018 Population – Southern Health-Santé Sud Zone 1 (former North Area) 5 Zone 2 (former Mid Area) 6 Zone 3 (former West Area) 7 Zone 4 (former East Area) 8 9 10 Year Population Growth (2008-2018) Manitoba RHA Comparisons 9 11 Age Group Comparisons 12 District and Municipal Population Change 15 Indigenous Population 16 Map of Region This publication is available in alternate format upon request. 2 Population Statistics 2018| Southern Health-Santé Sud ABOUT THIS REPORT The population data shown in this report is based on records of residents actively registered with Manitoba Health as of June 1, 2018 and published by Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living (http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/population/). This population database is considered a reliable and accurate estimate of population sizes, and is helpful for understanding trends and useful for health planning purposes. The Indigenous population has also been updated in March 2019 by the Indigenous Health program with the great help of Band Membership clerks. Please note that in 2018, international students, their spouses, and dependents were excluded because they were no longer eligible for provincial health insurance. This has impacted the population counts by approximately 10,000, largely from WRHA, compared to previous reports. Municipal Amalgamations A series of municipal amalgamations came into effect as of January 1, 2015. A map of Southern -

Preservings #09 Part

-being the Newsletter of the Hanover Steinbach Historical Society Inc. Special Double Issue - Part Two Price $10.00 No. 9, December, 1996 “A people who have not the pride to record their history will not long have the virtues to make their history worth recording; and no people who are indifferent to their past need hope to make their future great.”Jan Gleysteen Feature Story: Steinbach Jakob M. Barkman 1824-75: Father of Steinbach by Delbert F. Plett Family background. Jakob M. Barkman was born in Rückenau, Molotschna Colony, South Russia, to his par- ents Martin J. Barkman (1796-1872) and Katharina Regier (1800-66). His father was the son of Jakob Bergmann (1756-ca.1819) and Katharina Wiens (Note One). Henry Schapansky has written that the information on Jakob Bergmann is speculative but that he might have been the son of Jakob Bergmann (died 1780) who in turn may have been the son of Abraham Bergmann (1708-77) listed in the 1776 census as resident in Neuedorf, Prussia: letter Nov. 28, 1992. Katharina Regier came from “royal” lineage as Mennonites go, being the granddaughter of Bishop Peter Epp (1725-89) of Danzig, West Prussia. He was a devoted leader of his people and instrumental in organizing the emigration to Russia. He encouraged his children to emi- grate. House barn combination of Martin J. Barkman in Rückenau, Mol. where Jakob M. Barkman was born and Katherina’s parents were Katharina Epp (b. raised. Here the Russian Czar visited the Barkman family in 1825 and ate a meal. It may well be that the 1764) and Johann “Hans” Regier (b. -

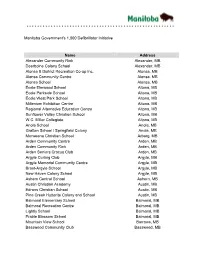

Manitoba Government's 1,000 Defibrillator Initiative Name Address

Manitoba Government's 1,000 Defibrillator Initiative Name Address Alexander Community Rink Alexander, MB Deerboine Colony School Alexander, MB Alonsa & District Recreation Co-op Inc. Alonsa, MB Alonsa Community Centre Alonsa, MB Alonsa School Alonsa, MB École Elmwood School Altona, MB École Parkside School Altona, MB École West Park School Altona, MB Millenium Exhibition Centre Altona, MB Regional Alternative Education Centre Altona, MB Sunflower Valley Christian School Altona, MB W.C. Miller Collegiate Altona, MB Anola School Anola, MB Grafton School / Springfield Colony Anola, MB Morweena Christian School Arborg, MB Arden Community Centre Arden, MB Arden Community Rink Arden, MB Arden Seniors Crocus Club Arden, MB Argyle Curling Club Argyle, MB Argyle Memorial Community Centre Argyle, MB Brant-Argyle School Argyle, MB New Haven Colony School Argyle, MB Ashern Central School Ashern, MB Austin Christian Academy Austin, MB Edrans Christian School Austin, MB Pine Creek Hutterite Colony and School Austin, MB Balmoral Elementary School Balmoral, MB Balmoral Recreation Centre Balmoral, MB Lightly School Balmoral, MB Prairie Blossom School Balmoral, MB Mountain View School Barrows, MB Basswood Community Club Basswood, MB Agassiz Adult Education Centre Beausejour, MB Beausejour Early Years School Beausejour, MB Hofer School / Greenwald Colony Beausejour, MB Network 4 Change Alternative Education Centre Beausejour, MB Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre Beausejour, MB Sunrise Divisional Centre Beausejour, MB Sunrise Education Centre Beausejour, -

Seeds from the Steppe: Mennonites, Horticulture, and the Construction of Landscapes on Manitoba's West Reserve, 1870-1950

Seeds from the Steppe: Mennonites, Horticulture, and the Construction of Landscapes on Manitoba's West Reserve, 1870–1950 by Susan Jane Fisher A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2017 by Susan Jane Fisher Abstract In this study, I offer a new research direction on the history of the Canadian prairie West with a joint focus on emotional history, life stories, and horticulture among the Mennonite immigrants from imperial Russia, who first assembled villages on Manitoba’s West Reserve in the 1870s. In this study, I trace oral culture, expressions of emotion, and the inter-generational transfer and preservation of botanical materials and traditions, in order to help us understand how individuals within a distinct ethno-religious group and in a colonial setting, experienced immigration and resettlement, and constructed landscapes accordingly. In the processes of their encounter, construction, and remembering, landscapes in history entail intricate myths and emotional attachments, whether they are explicitly known or implicitly understood. I argue that traditions of horticulture and homemaking, and the myths and memories surrounding prairie settlement, are creative acts through which West Reserve Mennonites at once reinforce settler-colonial agendas of success in the Canadian prairie West, and tie themselves emotionally to both a real and imagined history as a quiet, self-sufficient, agrarian people. Memoirs, diaries, newspapers, material artefacts, and oral histories connected to people on the West Reserve demonstrate that late nineteenth century Mennonite immigrants placed significant emotional value on the plant materials they carried with them in the hopes of reestablishing their sectarian, agrarian communities on the Canadian prairie. -

Winkler Voice 012518.Indd

Automotive Glass Chip Repairs Tinting JUST ARRIVED Farm Equipment Auto Accessories NEW 2018 LEGO 204-325-8387 150C Foxfi re Trail Winkler, MB (204)325-4012 600 Centennial St., Winkler, MB Winkler Morden VOLUME 9 EDITION 4 THURSDAY, JANUARY 25, 2017 VVLocally ownedoiceoice & operated - Dedicated to serving our communities Journey for Sight hunts for snow PHOTO BY LORNE STELMACH/VOICE The lack of snow in the Pembina Valley region meant this group of nine snowmobilers had to come up with a plan B Saturday for the annual Journey For Sight fundraiser in support of the Lions Eye Bank of Manitoba and Northwest Ontario. Meeting in Morden, they hauled their snowmobiles east in search of snow, and in the end they topped last year’s total by bringing in close to $10,000. For more, see Pg. 8. news > sports > opinion > community > people > entertainment > events > classifi eds > careers > everything you need to know 2 The Winkler Morden Voice Thursday, January 25, 2018 The Winkler Morden Voice Thursday, January 25, 2018 3 GVC students put their ‘skillz’ to the test By Ashleigh Viveiros group, but there are other [fi elds of study] in the school that could easily Garden Valley Collegiate students tap into this.” got the chance to put their classroom The participating courses tested stu- smarts to the test last week at the fi rst dents on what they’ve been learning ever GVC Skillz Competition. this semester through practical chal- Students enrolled in some of the lenges. Winkler high school’s technical vo- The business students had to create cational electives spent Jan. -

Manitoba Landscape

Published in the interest o f the best in the religious, social, and economic phases o f Mennonite culture Bound Volumes Mennonite Life is available in a series of bound volumes as follows: 1. Volume M il (1946-48) $6 2. Volume IV-V (1949-50) $5 3. Volume VI-VII (1951-52) $5 4. Volume VIII-IX (1953-54) $5 If ordered directly from Mennonite Life all four volumes are available at $18. Back Issues Wanted! Our supply of the first issue of Mennonite Life, January 1946, and January 1948, is exhausted. We would appreciate it if you could send us your copies. For both copies we would extend your subscription for one year. Address all correspondence to MENNONITE LIFE North Newton, Kansas COVER Manitoba Landscape Photography by Gerhard Sawatzky MENNONITE LIFE An Illustrated Quarterly EDITOR Cornelius Krahn ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR John F. Schmidt ASSOCIATE EDITORS Harold S. Bender S. F. Pannabecker J. Winfield Fretz Robert Kreider Melvin Gingerich J. G. Rempel N. van der Zijpp Vol. XI July, 1956 No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Contributors............................................................................................... ............................... 2 Russian Baptists and Mennonites............................................................. ...Cornelius Krahn 99 Else Krueger Pursues Art as a Hobby...................................................... ................................... 102 Manitoba Roundabout............................................................................... ........Victor Peters 104 Life in a Mennonite -

Spring Road Restrictions Map 2021 Order #3

Level 1 spring road restrictions means: a) On a single steering axle of a single or tandem drive truck tractor: Les restrictions de niveau 1 se définissent comme suit. - 10 kg per millimetre width of tire up to a maximum of 5,500 kg on all highways. a) Pour un essieu directeur simple d'un véhicule tracteur à essieu simple ou à essieux MANITOBA b) On a single steering axle of a straight truck or a tridem drive truck tractor: directeurs tandem : - - Tire size 305 mm or less: 10 kg per millimeter width of tire up to a maximum of 5,500 10 kg par millimètre de largeur de pneu, jusqu'à un maximum de 5 500 kg, et ce sur 6 toutes les routes; kg on all highways. Oxford House - Tire size greater than 305 mm: 9 kg per millimeter width of tire up to a maximum of b) pour un essieu directeur simple d'un camion porteur ou d'un véhicule tracteur équipé 2021 SPRING ROAD RESTRICTIONS (ORDER # 3) 6,570 kg on all highways. d'un essieu tridem moteur : c) On a tandem steering axle group of a straight truck: - pour des pneus de 305 mm ou moins, 10 kg par millimètre de largeur de pnew, Snow jusqu'à un maximum de 5 500 kg, et ce sur toutes les routes; Lake 393 - 9 kg per mm width of tire multiplied by 0.90 (download factor) up to a maximum of - pour des pneus de plus de 305 mm, 9 kg par millimètre de largeur de pneu, jusqu'à un Gods River Wabowden RESTRICTIONS CONCERNANT LES ROUTES AU 12,240 kg on RTAC Routes or Class A1 highways and up to a maximum of 9,900 kg 395 on Class B1 highways. -

2016 Population Report

1 Population Statistics 2016 | Southern Health-Santé Sud Published: April 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 3 3 Municipal Amalgamations for 2016 4 2016 Population – Southern Health-Santé Sud North Area 5 Mid Area 6 West Area 7 East Area 8 9 10 Year Population Growth (2006-2016) Manitoba RHA Comparisons 9 11 Age Group Comparisons 12 District and Municipal Population Change 15 Indigenous Population 16 Map of Region 2 Population Statistics 2016 | Southern Health-Santé Sud BACKGROUND The population data shown in this report are based on records of residents registered with Manitoba Health as of June 1, 2016 and published by Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living (http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/population/). This population database is considered a reliable and accurate estimate of population sizes, and is helpful for understanding trends and useful for health planning purposes. The Indigenous population has also been updated in March 2017 by the Indigenous Health program with the great help of Band Membership clerks. Southern Health-Santé Sud covers an area of 27,025 square kilometers in southern Manitoba. It stretches up from the 49th parallel and borders the United States of America to the south, and the Ontario border to the east. The region lies along the route of the Trans-Canada highway, and includes the south-west edge of Lake Manitoba down to the Pembina escarpment in the west. Southern Health-Santé Sud is one of five regional health authorities (RHA) in Manitoba. The other four RHAs include: Northern Health Region, Interlake-Eastern RHA, Prairie Mountain Health, and WRHA (Winnipeg). -

List of All Sites on File with the Contaminated/Impacted Sites Program

LIST OF ALL SITES ON FILE WITH THE CONTAMINATED/IMPACTED SITES PROGRAM Disclaimer This is not the "Contaminated Sites List". This list contains all the sites for which the Contaminated/Impacted Program of Manitoba Conservation and Climate maintains a file. This list is intended only as a preliminary screening tool for identification of potentially impacted or contaminated sites in Manitoba. This list alone should not be relied upon to determine if contamination is present on a site. Contamination from on-site activities or neighbouring properties may be present but have not been brought to the attention of this department. This list includes: * Sites where remediation has been completed * Sites where remediation is currently being conducted * Sites that are also on the Designated Impacted and Designated Contaminated Sites Lists A complete Environmental File Search is recommended to confirm all the information Manitoba Conservation and Climate maintains on a site. Some sites listed here are also listed on the Desginated Contaminated Sites List and the Designated Impacted Sites List. These lists are found under the header Sites Lists on the Contaminated/Impacted Sites Program website at: https://www.gov.mb.ca/sd/waste_management/contaminated_sites/index.html As of April 6, 2021 LIST OF ALL SITES ON FILE WITH THE CONTAMINATED/IMPACTED SITES PROGRAM File Site Name Address City/Town/RM Number 20086 POPLAR BAY TRADING POST HWY 315 4 KM N OF HWY Alexander 313 42382 STILL COVE 67 ELSIE STREET, STILL Alexander COVE 46320 RABE FARMS NW 15-10-22 WPM Alexander 47765 MANITOBA HYDRO - MCARTHUR FALLS MCARTHUR FALLS Alexander GS GENERATING STATION 49792 MANITOBA HYDRO - POINTE DU BOIS 4.75 MILES WEST OF Alexander RAIL SPUR POINTE DU BOIS 54469 MANITOBA HYDRO - GREAT FALLS GS SE 35-17-11 E Alexander CONSTRUCTION DUMP 58740 MANITOBA INFRASTRUCTURE AND NW 11-18-07 E Alexander TRANSPORTATION - GRAND BEACH MAINTENANCE YARD 58759 MANITOBA CONSERVATION PINE FALLS NE CORNER OF HWY 11 Alexander HOSE PLANT AND HWY 304.