Blaming Halo: the Effects of Violent Video Games and What Should Be Done About Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weighing the Trade-Offs of a Direct Presence in Japan's Rare And

Special Report Weighing the Trade-offs of a Direct Presence in Japan’s Rare and Orphan Drug Market January 2020 Contents Summary ................................................................2 Background on increasing interest in Japan among rare and orphan biopharma companies ....................3 Attractive market fundamentals at the heart of the opportunity ............................................................4 Retaining control helps avoid poor partnering outcomes and entanglements ..................................6 The market is not without its challenges ...................7 A direct presence will not make business sense for everyone ............................................................. 10 Checklist for prospective Japan entrants ................. 11 Endnotes/About the Authors ................................. 12 About L.E.K. Consulting L.E.K. Consulting is a global management consulting firm that uses deep industry expertise and rigorous analysis to help business leaders achieve practical results with real impact. We are uncompromising in our approach to helping clients consistently make better decisions and deliver improved performance. The firm advises and supports organizations that are leaders in their sectors, including the largest private and public sector organizations, private equity firms, and emerging entrepreneurial businesses. Founded in 1983, L.E.K. employs more than 1,600 professionals across the Americas, Asia-Pacific and Europe. For more information, go to www.lek.com. 1 Summary Japan has long sought to foster an attractive market for orphan you consider the benefits of avoiding entanglement with a drugs, with specific provisions made to encourage the development partner and the challenges of managing relationships with of therapies for rare and orphan diseases as early as 1972.1 The potential licensing partners. measures and incentives that followed made the orphan and rare • But setting up a direct presence in Japan is not for model economically viable in Japan, yet companies operating in everyone. -

2006 2012 2013 2014 Introducing HALO® 2 Fused-Core®

Introducing HALO® 2 Fused-Core® UHPLC Columns From Advanced Materials Technology Rugged ∙ High Efficiency ∙ Low Back Pressure HALO 2 Fused-Core particles are designed to address the disadvantages inherent in existing sub-2 micron non-core UHPLC columns. HALO 2 UHPLC columns have all of the advantages of sub-2 µm non-core particle columns and will deliver 300,000 plates per meter efficiency (higher than existing non-core sub-2 µm columns). Manufactured with 1.0 µm frits on the column inlet, HALO 2 columns are less susceptible to column plugging. These columns can be used up to 1,000 bar (14,500 psi), but will actually produce ~20% lower back pressure than most commercially available sub-2 µm UHPLC columns under the same conditions. 1 Advantages of HALO 2 Fused-Core Columns vs. Sub-2 µm Non-core UHPLC Columns · Fused-Core UHPLC columns with ~300K plates per meter · All of the advantages of sub-2 µm non-core particles at lower - Higher efficiency than existing non-core sub-2 µm columns operating pressures · Longer column lifetime – more injections, less downtime - High speed and efficiency with short columns - Due to Fused-Core 2 micron particle architecture, 1 micron - Improved productivity from faster analyses frits can be used on the column inlet - Less solvent usage from shorter analysis times - 1 micron frits are less likely to be plugged by UHPLC samples - High resolution and peak capacity in longer columns or mobile phase contaminants than typical 0.2 – 0.5 µm - Sharper, taller peaks = better sensitivity and lower LOD frits on sub-2 -

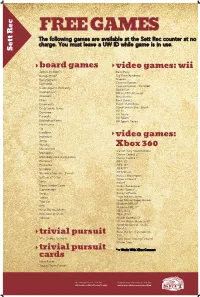

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Game Enforcer Is Just a Group of People Providing You with Information and Telling You About the Latest Games

magazine you will see the coolest ads and Letter from The the most legit info articles you can ever find. Some of the ads include Xbox 360 skins Editor allowing you to customize your precious baby. Another ad is that there is an amazing Ever since I decided to do a magazine I ad on Assassins Creed Brotherhood and an already had an idea in my head and that idea amazing ad on Clash Of Clans. There is is video games. I always loved video games articles on a strategy game called Sid Meiers it gives me something to do it entertains me Civilization 5. My reason for this magazine and it allows me to think and focus on that is to give you fans of this magazine a chance only. Nowadays the best games are the ones to learn more about video games than any online ad can tell you and also its to give you a chance to see the new games coming out or what is starting to be making. Game Enforcer is just a group of people providing you with information and telling you about the latest games. We have great ads that we think you will enjoy and we hope you enjoy them so much you buy them and have fun like so many before. A lot of the games we with the best graphics and action. Everyone likes video games so I thought it would be good to make a magazine on video games. Every person who enjoys video games I expect to buy it and that is my goal get the most sales and the best ratings than any other video game magazine. -

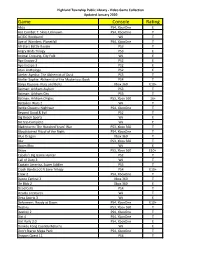

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Architecting & Launching the Halo 4 Services

Architecting & Launching the Halo 4 Services SRECON ‘15 Caitie McCaffrey! Distributed Systems Engineer @Caitie CaitieM.com • Halo Services Overview • Architectural Challenges • Orleans Basics • Tales From Production Presence Statistics Title Files Cheat Detection User Generated Content Halo:CE - 6.43 million Halo 2 - 8.49 million Halo 3 - 11.87 million Halo 3: ODST - 6.22 million Halo Reach - 9.52 million Day One $220 million in sales ! 1 million players online Week One $300 million in sales ! 4 million players online ! 31.4 million hours Overall 11.6 million players ! 1.5 billion games ! 270 million hours Architectural Challenges Load Patterns Load Patterns Azure Worker Roles Azure Table Azure Blob Azure Service Bus Always Available Low Latency & High Concurrency Stateless 3 Tier ! Architecture Latency Issues Add A Cache Concurrency " Issues Data Locality The Actor Model A framework & basis for reasoning about concurrency A Universal Modular Actor Formalism for Artificial Intelligence ! Carl Hewitt, Peter Bishop, Richard Steiger (1973) Send A Message Create a New Actor Change Internal State-full Services Orleans: Distributed Virtual Actors for Programmability and Scalability Philip A. Bernstein, Sergey Bykov, Alan Geller, Gabriel Kliot, Jorgen Thelin eXtreme Computing Group MSR “Orleans is a runtime and programming model for building distributed systems, based on the actor model” Virtual Actors “An Orleans actor always exists, virtually. It cannot be explicitly created or destroyed” Virtual Actors • Perpetual Existence • Automatic Instantiation • Location Transparency • Automatic Scale out Runtime • Messaging • Hosting • Execution Orleans Programming Model Reliability “Orleans manages all aspects of reliability automatically” TOO! TOO! TOO! Performance & Scalability “Orleans applications run at very high CPU Utilization. -

![Arxiv:1510.04980V2 [Astro-Ph.CO] 22 Nov 2015 Eet Ta.21;D Aprne L 04.Hwvr Radio However, 2014)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3277/arxiv-1510-04980v2-astro-ph-co-22-nov-2015-eet-ta-21-d-aprne-l-04-hwvr-radio-however-2014-983277.webp)

Arxiv:1510.04980V2 [Astro-Ph.CO] 22 Nov 2015 Eet Ta.21;D Aprne L 04.Hwvr Radio However, 2014)

DRAFT VERSION JULY 30, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11 THE SCALING RELATIONS AND THE FUNDAMENTAL PLANE FOR RADIO HALOS AND RELICS OF GALAXY CLUSTERS 1,2 1 1 Z.S. YUAN ,J.L.HAN ,Z.L.WEN 1National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20A Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100012, China; [email protected] 2School of Physics, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China Draft version July 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Diffuse radio emission in galaxy clusters is known to be related to cluster mass and cluster dynamical state. We collect the observed fluxes of radio halos, relics, and mini-halos for a sample of galaxy clusters from the literature, and calculate their radio powers. We then obtain the values of cluster mass or mass proxies from previous observations, and also obtain the various dynamical parameters of these galaxy clusters from optical and X-ray data. The radio powers of relics, halos, and mini-halos are correlated with the cluster masses or mass proxies, as found by previous authors, with the correlations concerning giant radio halos being, in general, the strongest ones. We found that the inclusion of dynamical parameters as the third dimension can significantly reduce the data scatter for the scaling relations, especially for radio halos. We therefore conclude that the substructures in X-ray images of galaxy clusters and the irregular distributions of optical brightness of member galaxies can be used to quantitatively characterize the shock waves and turbulence in the intracluster medium responsible for re-accelerating particles to generate the observed diffuse radio emission. -

Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design

The London School of Economics and Political Science Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design Siobhán Thomas A thesis submitted to the Department of Management of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, June 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 66,515 words. 2 Abstract The aim of this qualitative research study was to develop an understanding of the lived experiences of game designers from the particular vantage point of intersomatic awareness. Intersomatic awareness is an interbodily awareness based on the premise that the body of another is always understood through the body of the self. While the term intersomatics is related to intersubjectivity, intercoordination, and intercorporeality it has a specific focus on somatic relationships between lived bodies. This research examined game designers’ body-oriented design practices, finding that within design work the body is a ground of experiential knowledge which is largely untapped. To access this knowledge a hermeneutic methodology was employed. The thesis presents a functional model of intersomatic awareness comprised of four dimensions: sensory ordering, sensory intensification, somatic imprinting, and somatic marking. -

ZERO TOLERANCE: Policy on Supporting 1St Party Xbox Games

ZERO TOLERANCE: Policy on Supporting 1st Party Xbox Games FEBRUARY 6, 2009 TRAINING ALERT Target Audience All Xbox Support Agents Introduction This Training Alert is specific to incorrect referral of game issues to game developers and manufacturers. What’s Important Microsoft has received several complaints from our game partners about calls being incorrectly routed to them when the issue should have been resolved by a Microsoft support agent at one of our call centers. This has grown from an annoyance to seriously affecting Microsoft's ability to successfully partner with certain game manufacturers. To respond to this, Microsoft is requesting all call centers to implement a zero tolerance policy on incorrect referrals of Games issues. These must stay within the Microsoft support umbrella through escalations as needed within the call center and on to Microsoft if necessary. Under no circumstances should any T1 support agent, T2 support staff, or supervisor refer a customer with an Xbox game issue back to the game manufacturer, or other external party. If there is any question, escalate the ticket to Microsoft. Please also use the appropriate article First-party game titles include , but are not limited to , the following examples: outlining support • Banjo Kazooie: Nuts & Bolts boundaries and • Fable II definition of 1 st party • Gears of War 2 games. • Halo 3 • Lips VKB Articles: • Scene It? Box Office Smash • Viva Pinata: Trouble In Paradise #910587 First-party game developers include , but are not limited to, the following #917504 examples: • Bungie Studios #910582 • Bizarre Creations • FASA Studios • Rare Studios • Lionhead Studios Again, due to the seriousness of this issue, if any agent fails to adhere to this policy, Microsoft will request that they be permanently removed from the Microsoft account per our policies for other detrimental kinds of actions. -

Score Pause Game Settings Fire Weapon Reload/Action Switch Weapo

Fire Weapon Reload/Action ONLINE ENABLED Switch Weapons Melee Attack Jump Swap Grenades Flashlight Zoom Scope (Click) Throw Grenade E-brake (Warthog) Boost (Vehicles) Crouch (Click) Score Pause Game Settings Get the strategy guide primagames.com® ® 0904 Part No. X10-96235 SAFETY INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS About Photosensitive Seizures Secret Transmission ........................................................................................... 2 A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who Master Chief .......................................................................................................... 3 have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these Breakdown of Known Covenant Units ......................................................... 4 “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or Controller ............................................................................................................... 6 face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from Mjolnir Mark VI Battle Suit HUD ..................................................................... 8 falling down or striking -

System Title Qty Genre Max # of Players Esrb Rating Xbox

MAX # OF SYSTEM TITLE QTY GENRE PLAYERS ESRB RATING XBOX 360 Blur 1 Racing 4 E XBOX 360 Call of Duty 2 1 FPS 4 T XBOX 360 Call of Duty 3 4 FPS 16* T XBOX 360 Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare 1 FPS 2 M XBOX 360 Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 FPS 4 M XBOX 360 Call of Duty: Black Ops II 2 FPS 4 M XBOX ONE Call of Duty: Black Ops III 1 FPS 4 M XBOX ONE Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare 1 FPS 2 M XBOX 360 Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 2 FPS 4 M XBOX 360 Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 1 FPS 4 M XBOX ONE Call of Duty: Modern Warfare Remastered 1 FPS 2 M XBOX 360 Call of Duty: World at War 1 FPS 4 M XBOX ONE Call of Duty: WWII 1 FPS 2 M XBOX 360 Cars 2 1 Racing 4 E XBOX 360 Dance Central 1 Dance (Kinect) 2 T XBOX 360 Dance Central 2 1 Dance (Kinect) 2 T XBOX 360 Diablo III 1 Third-Person Shooter (TPS) 4 M XBOX 360 Disney Universe 1 Adventure 4 E XBOX 360 Gears of War 2 2 Third-Person Shooter (TPS) 4* M XBOX 360 Gears of War 3 1 Third-Person Shooter (TPS) 2 M XBOX ONE Gears of War 4 1 Third-Person Shooter (TPS) 2 M XBOX 360 Halo 3: ODST 4 FPS 16* M XBOX 360 Halo 4 1 FPS 16* M XBOX 360 Halo Reach 2 FPS 16* M XBOX 360 Hip Hop Dance 1 Dance (Kinect) 2 T XBOX 360 Kinect Adventures 1 Adventure (Kinect) 2 E XBOX 360 Kung Fu Panda 2 1 Action (Kinect) 1 E XBOX 360 Left 4 Dead 2 1 Third-Person Shooter (TPS) 2 M XBOX 360 Legends of Wrestlemania 1 Wrestling 4 T XBOX 360 Lego Batman 1 Adventure 2 E XBOX 360 Lego Harry Potter Years 1 - 4 1 Adventure 2 E XBOX 360 Lego Indiana Jones 1 Adventure 2 E XBOX 360 Lego Indiana Jones 2 1 Adventure 2 E XBOX 360 Madden 2011 2 -

Exploring Skill Sets for Computer Game Design Programs Bungie, Inc

Exploring Skill Sets for Computer Game Design Programs Bungie, Inc. Employees Share Their Insights by Markus Geissler, Professor and Deputy Sector Navigator, ICT/Digital Media, Greater Sacramento Region Abstract: Based upon several responses from employees at Bungie, Inc., a developer of computer games based in Seattle, to both general and specific questions about the skills sets required for students who wish to work in the computer game industry, technical knowledge, especially in computer programming, but, more importantly, solid interpersonal skills, the ability to think as part of a team consisting of individuals with varying skill sets, and the strength to solve complex problems should be essential program student learning outcomes (PSLOs) for Computer Game Design or similar academic programs. To that end academic program designers should strongly consider an interdisciplinary preparation which includes coursework that addresses both technical and professional PSLOs and which may be offered by content experts across multiple academic departments. Author’s note: In May 2019 the members of Cosumnes River College’s (CRC) Computer Information Science faculty discussed whether or not to add a Game Design component to the department’s course offerings, possibly to complement existing programs at nearby colleges. To better inform the discussion I volunteered to get some industry input via a family friend who works at Bungie, Inc., an American video game developer based in Bellevue, WA which is the developer of computer games such as Destiny, Halo, Myth, Oni, and Marathon. Several Bungie employees were kind enough to respond first to my initial request for a conversation and then specific questions by CRC’s CIS faculty members which I forwarded to the folks at Bungie.