A Simple Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

13Th February 2021 Dear All Tomorrow Is One of Those Strangely

13th February 2021 Dear all Tomorrow is one of those strangely named Sundays – the Sunday Next Before Lent. I’m not quite sure why the ‘next’ comes in , but it interesting that both of the penitential seasons in the church calendar have a countdown… 3rd Sunday before Advent, 2nd Sunday before Lent etc.. We often see Advent and Lent as periods leading up to the exciting seasons of Christmas and Easter, but the church calendar requires us to take them seriously in their own right. What will we be doing for Lent? Let’s gear ourselves up… get ready… set… and, go! In a recent letter I suggested a few books or courses you might be interested in. I also invited anyone to request an ash cross stone, to be left on their doorstep. Please let me know by Wednesday, so that I know how many to prepare. Tomorrow’s service details: Readings – 2 Kings 2: 1-12; 2 Corinthians 4: 3-6; Psalm 50: 1-6; Mark 9: 2-9 Hymns: Jesus on the mountain peak; ‘Tis good, Lord, to be here. Lent Course: Next Thursday is the day after Ash Wednesday, and so we will put our study of Mark’s gospel on hold, and instead follow our Lent Course. The details are the same as always: We will meet on Zoom, Thursdays 2.30-3.30ish pm. The Zoom details are: https://us04web.zoom.us/j/8109399155?pwd=STVVTU44RzJxTFFHbTY1MnI0bjJ2Zz09 Meeting ID: 810 939 9155 Passcode: 1w2C9a Please note that, on Thursday 25th February the Lent Course will take place in the morning , at 10.30am. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

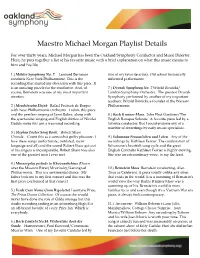

Michael Morgan Playlist

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

Czech Philharmonic

Biography Czech Philharmonic “The Czech Philharmonic is among the very few orchestras that have managed to preserve a unique identity. In a music world that is increasingly globalized and uniform, the Orchestra’s noble tradition has retained authenticity of expression and sound, making it one of the world's artistic treasures. When the orchestra and Czech government asked me to succeed beloved Jiří Bělohlávek, I felt deeply honoured by the trust they were ready to place in me. There is no greater privilege for an artist than to become part of and lead an institution that shares the same values, the same commitment and the same devotion to the art of music.” Semyon Bychkov, Chief Conductor & Music Director The 125 year-old Czech Philharmonic gave its first concert – an all Dvořák programme which included the world première of his Biblical Songs, Nos. 1-5 conducted by the composer himself - in the famed Rudolfinum Hall on 4 January 1896. Acknowledged for its definitive interpretations of Czech composers, whose music the Czech Philharmonic has championed since its formation, the Orchestra is also recognised for the special relationship it has to the music of Brahms and Tchaikovsky - friends of Dvořák - and to Mahler, who gave the world première of his Symphony No. 7 with the Orchestra in 1908. The Czech Philharmonic’s extraordinary and proud history reflects both its location at the very heart of Europe and the Czech Republic’s turbulent political history, for which Smetana’s Má vlast (My Homeland) has become a potent symbol. The Orchestra gave its first full rendition of Má vlast in a brewery in Smíchov in 1901; in 1925 under Chief Conductor Václav Talich, Má vlast was the Orchestra’s first live broadcast and, five years later, the first work that the Orchestra committed to disc. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

Gardiner's Schumann

Sunday 11 March 2018 7–9pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT GARDINER’S SCHUMANN Schumann Overture: Genoveva Berlioz Les nuits d’été Interval Schumann Symphony No 2 SCHUMANN Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Recommended by Classic FM Streamed live on YouTube and medici.tv Welcome LSO News On Our Blog This evening we hear Schumann’s works THANK YOU TO THE LSO GUARDIANS WATCH: alongside a set of orchestral songs by another WHY IS THE ORCHESTRA STANDING? quintessentially Romantic composer – Berlioz. Tonight we welcome the LSO Guardians, and It is a great pleasure to welcome soloist extend our sincere thanks to them for their This evening’s performance of Schumann’s Ann Hallenberg, who makes her debut with commitment to the Orchestra. LSO Guardians Second Symphony will be performed with the Orchestra this evening in Les nuits d’été. are those who have pledged to remember the members of the Orchestra standing up. LSO in their Will. In making this meaningful Watch as Sir John Eliot Gardiner explains I would like to take this opportunity to commitment, they are helping to secure why this is the case. thank our media partners, medici.tv, who the future of the Orchestra, ensuring that are broadcasting tonight’s concert live, our world-class artistic programme and youtube.com/lso and to Classic FM, who have recommended pioneering education and community A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO tonight’s concert to their listeners. The projects will thrive for years to come. concert at the Barbican, as we are joined by performance will also be streamed live on WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S GROUPS one of the Orchestra’s regular collaborators, the LSO’s YouTube channel, where it will lso.co.uk/legacies Sir John Eliot Gardiner. -

Gala2o2o Saturday, October 17

VIRTUAL GALA2O2O SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17 THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT AND FOR JOINING US THIS EVENING Dear Friends, Welcome to the (very unusual and hopefully unique) 17th annual Reach for the Stars Gala! Six months ago, it was unthinkable that we would not be gathering together to celebrate tonight. We envisioned the ballroom, the tables, the speakers, and the dancing. Now it is up to you to take a spin at home. Right now, advocates are talking with survivors, assisting with paperwork, safety planning, and counseling them as they face an (even more) uncertain future. Right now, our prevention staff is working with teachers, coaches, and administrators on professional development programs, classroom presentations, team trainings, and parent meetings. Right now, our house is home to only half of the families we are sheltering—four families remain in a hotel after fully emptying the shelter when COVID hit. We clean like never before and advocate like we always have—in a world that looks so different. And as you read this, right now, we are getting ready to host a virtual gala for the first time. We are excited to share this evening with hundreds of people over the internet, something we never envisioned when we planned it. We are doing this with your help and our shared conviction that the show must go on because the work goes on. When our office lights went out on March 16, dozens of makeshift desks got set up. Cell phones got charged. We kept working. REACH staff kept calling survivors, partnering with schools, providing shelter—we kept doing it all. -

Berlioz's Les Nuits D'été

Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été - A survey of the discography by Ralph Moore The song cycle Les nuits d'été (Summer Nights) Op. 7 consists of settings by Hector Berlioz of six poems written by his friend Théophile Gautier. Strictly speaking, they do not really constitute a cycle, insofar as they are not linked by any narrative but only loosely connected by their disparate treatment of the themes of love and loss. There is, however, a neat symmetry in their arrangement: two cheerful, optimistic songs looking forward to the future, frame four sombre, introspective songs. Completed in 1841, they were originally for a mezzo-soprano or tenor soloist with a piano accompaniment but having orchestrated "Absence" in 1843 for his lover and future wife, Maria Recio, Berlioz then did the same for the other five in 1856, transposing the second and third songs to lower keys. When this version was published, Berlioz specified different voices for the various songs: mezzo-soprano or tenor for "Villanelle", contralto for "Le spectre de la rose", baritone (or, optionally, contralto or mezzo) for "Sur les lagunes", mezzo or tenor for "Absence", tenor for "Au cimetière", and mezzo or tenor for "L'île inconnue". However, after a long period of neglect, in their resurgence in modern times they have generally become the province of a single singer, usually a mezzo-soprano – although both mezzos and sopranos sometimes tinker with the keys to ensure that the tessitura of individual songs sits in the sweet spot of their voices, and transpositions of every song are now available so that it can be sung in any one of three - or, in the case of “Au cimetière”, four - key options; thus, there is no consistency of keys across the board. -

MU 270/Voice

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona COURSE SYLLABUS MU 270 - Performance Seminar/VOICE –Spring 2014 Time and Location: T 1-1:50 Bldg. 24-191 Instructor/ office: Lynne Nagle; Bldg. 24 – 155 and 133 Office Hours: M 9:30-10:30; T11:00-12:00; T 4:00-5:00; others TBA Phone: (909) 869-3558 e-mail: [email protected] Textbook and Supplies: No textbook is needed; notebook required. Course Objectives: To provide a laboratory recital situation wherein students may perform for each other, as well as for the instructor, for critical review. They will share song literature, musical ideas, production techniques, stylistic approaches, etc., in order to learn from each other as well as from the instructor. Assignments and Examinations:!In-class performances: You will be expected to perform a minimum of 3 times (5 for upper division) during each quarter, each performance taking place on a different day. Songs may be repeated for performance credit, but lower division students must perform at least 3 different songs and upper division at least 4 different songs. Please provide a spoken translation when performing in a foreign language. A brief synopsis of an opera, musical or scene is also appropriate if time allows. ALL PERFORMANCES IN SEMINAR ARE TO BE MEMORIZED except for traditional use of the score for oratorio literature. You are also expected to contribute to the subsequent discussion. Concert Reports: TWO (2) typed reports on choral/vocal concerts, recitals or shows must be submitted by week 10 seminar or sooner. You may use any concert you have attended since the end of the previous quarter.