University of Łódź

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farrah Abraham Has Butt Implants? ‘Teen Mom’ Has Had ‘Significant Buttock Enhancement,’ Claims Surgeon

Farrah Abraham Has Butt Implants? ‘Teen Mom’ Has Had ‘Significant Buttock Enhancement,’ Claims Surgeon Inquisitor.com Farrah Abraham may have recently gone under the knife. According to a new report, a plastic surgeon believes the Teen Mom star’s backside is much larger now than it was when fans first met her in 2009. In an interview with Wetpaint Entertainment on February 25, Dr. Lyle Black, a Philadelphia- area plastic surgeon who has not operated on Farrah Abraham, claims she’s “most certainly” had work done. “[Farrah Abraham] has had significant buttock enhancement. Folks, this is no ‘allergic reaction!’ Previously, her buttocks were very flat, with almost no projection — the ‘booty’ part of the booty — and little definition along the banana zone (upper thigh just under the cheek), and flatness for what should be the sexy ‘smile’ of the buttock crease (from the deep inner thigh up and outward). All of these have been addressed with some serious additional ‘volume’ placed nicely into all the right places!” As for whether he believes Farrah Abraham received injections or implants, Dr. Black said there’s no way to be sure. However, when it comes to what he would recommend for a client of his own, he went with the injections. “Buttock implants are notorious for shifting in position, getting infected, or pressing uncomfortably on nerves, both short-term and long-term. After a brief recovery period, fat injections do not have any of these potential downsides.” In other Farrah Abraham news, the Teen Mom OG trailer was recently released, and in it, her co- stars are seen reacting to her return. -

Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2013 Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit Caitlin Rickert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rickert, Caitlin, "Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit" (2013). Master's Theses. 136. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/136 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT by Caitlin Rickert A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Communication Western Michigan University April 2013 Thesis Committee: Heather Addison, Ph. D., Chair Sandra Borden, Ph. D. Joseph Kayany, Ph. D. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT Caitlin Rickert, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study explores how The Biggest Loser, a popular television reality program that features a weight-loss competition, reflects and magnifies established stereotypes about obese individuals. The show, which encourages contestants to lose weight at a rapid pace, constructs a broken/fixed dichotomy that oversimplifies the complex issues of obesity and health. My research is a semiotic analysis of the eleventh season of the program (2011), focusing on three pairs of contestants (or “couples” teams) that each represent a different level of commitment to the program’s values. -

Maci Bookout Book

1 / 4 Maci Bookout Book Teen Mom OG's Maci Bookout 'Angry' After Telling Son Bentley About Father ... is the MacGuffin of the young-reader's book The Glove of Darth Vader (1992).. Looking for books by Maci Bookout? See all books authored by Maci Bookout, including Bulletproof, and I Wasn't Born Bulletproof: Lessons I've Learned (So .... Specifically, they want to know what's going on with Maci Bookout's marriage to ... Historical Classic Romance thru Time (Remembrance Series Book 1) eBook: .... Bulletproof by Maci Bookout and a great selection of related books, art and collectibles available now at AbeBooks.com.. Maci Bookout, the reality television megastar of Teen Mom and the New York Times bestselling author of Bulletproof, offers down-to-earth, .... #thebattleupstairs #pcosawarenessmonth, A post shared by Maci Bookout ... in next year's Guinness World Records book for two titles — longest female legs .... Maci Bookout has always been an open book about her life -- from being pregnant at 16 years old to becoming a doting mama to son Bentley .... Maci Bookout. A POST HILL PRESS BOOK ISBN (trade paperback): 978-1-68261-283-5 ISBN (hardcover): 978-1-61868-864-4 ISBN (eBook): ... The cast of Teen Mom OG, including Maci Bookout, Catelynn Lowell, Amber ... Cast In Amazon's Superhero Drama Series Based On Comic Book (неопр.. As of May 2020, the estimated net worth of Maci Bookout is $3 million, a fortune that she has amassed with her various reality shows and book .... The poetry book, entitled The Battle Upstairs, is being put out by Post Hill Press, the same company that published Maci's first book Bulletproof, as ... -

Tv Pg 01-04-11.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, January 4, 2011 7 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening January 4, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC No Ordinary Family V Detroit 1-8-7 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS Live to Dance NCIS Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX Glee Million Dollar Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC Demolition Man Demolition Man Crocodile Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike Animals Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET American Gangster The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show State 2 Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Matchmaker Matchmaker The Fashion Show Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local The Dukes of Hazzard The Dukes of Hazzard Canadian Bacon 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY 29 CNBC 57 Disney Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Daily Colbert Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Futurama Local 9 NBC-KUSA 37 USA 65 We DISC Local Local Dirty Jobs -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of Communications the “NEW TEEN MOMISM”: 16 and PREGNANT and T

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications THE “NEW TEEN MOMISM”: 16 AND PREGNANT AND THE NEW “TEEN MOM” IDENTITY A Thesis in Media Studies by Jacqueline N. Dunfee © 2012 Jacqueline N. Dunfee Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2012 ii The thesis of Jacqueline N. Dunfee was reviewed and approved* by the following: Michelle Rodino-Colocino Assistant Professor of Communications Thesis Advisor Matthew McAllister Professor of Communications Marie Hardin Associate Dean of Graduate Education College of Communications *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Teenage pregnancy in the U.S. has been represented in popular culture in quite contradictory ways: as a serious social problem and an enviable, even glamorous youth identity. One important case in point is the television franchise 16 and Pregnant, a show that, together with its spin-off series, demonize and glamorize teen pregnancy. Above all else, 16 and Pregnant produces the spectacle of the pregnant teen as a new identity for reality television. The purpose of this thesis is to show how the content of the series 16 and Pregnant reflects and array of historical, cultural, and political-economic factors. I adopt a feminist perspective in my political-economic and textual analysis of the show and related media. The following analysis draws on Douglas and Michaels’ (2004) conception of “new momism” and Murphy’s (2012) conception of “teen momism” and applies these terms to 16 and Pregnant to explain how teen moms are constructed as both morally reprehensible yet also desirable figures that echo neoliberal and postfeminist ideologies. -

"I Used to Be Fat": a Qualitative Analysis of Bariatric Surgery Patients

“I USED TO BE FAT” A QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF BARIATRIC SURGERY PATIENTS __________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Caudill College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Morehead State University _________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _________________________ by Steven W. Fife June 22, 2019 ProQuest Number:13905097 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 13905097 Published by ProQuest LLC ( 2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Accepted by the faculty of the Caudill College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, Morehead State University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree. ____________________________ Dr. Constance Hardesty Director of Thesis Master’s Committee: ________________________________, Chair Dr. Constance Hardesty _________________________________ Dr. Suzanne Tallichet _________________________________ Dr. Shondra Nash ________________________ Date “I USED TO BE FAT” A QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF BARIATRIC SURGERY PATIENTS Steven W. Fife Morehead State University, 2019 Director of Thesis: __________________________________________________ Dr. Constance Hardesty Obesity continues to be a growing threat to public and individual health in the United States of America. -

Body Curves and Story Arcs

Body Curves and Story Arcs: Weight Loss in Contemporary Television Narratives ! ! ! Thesis submitted to Jawaharlal Nehru University and Università degli Studi di Bergamo, as part of Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorate Program “Cultural Studies in Literary Interzones,” in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of ! Doctor of Philosophy ! ! by ! ! Margaret Hass ! ! ! Centre for English Studies School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi - 110067, India 2016 ! Table of Contents !Acknowledgements !Foreword iii Introduction: Body Curves and Story Arcs Between Fat Shame and Fat Studies 1 Liquid Modernity, Consumer Culture, and Weight Loss 5 Temporality and Makeover Culture in Liquid Modernity 10 The Teleology of Weight Loss, or What Jones and Bauman Miss 13 Fat Studies and the Transformation of Discourse 17 Alternative Paradigms 23 Lessons from Feminism: Pleasure and Danger in Viewing Fat 26 Mediatization and Medicalization 29 Fictional Roles, Real Bodies 33 Weight and Television Narratology 36 Addressing Media Texts 39 Selection of Corpus 43 ! Description of Chapters 45 Part One: Reality! TV Change in “Real” Time: The Teleologies and Temporalities of the Weight Loss Makeover 48 I. Theorizing the Weight Loss Makeover: Means and Ends Paradoxes 52 Labor Revealed: Exercise and Affect 57 ! Health and the Tyranny of Numbers 65 II. The Temporality of Transformation 74 Before/After and During 81 Temporality and Mortality 89 Weight Loss and Becoming an Adult 96 I Used to Be Fat 97 ! Jung und Dick! Eine Generation im Kampf gegen Kilos 102 III. Competition and Bodily Meritocracy 111 The Biggest Loser: Competition, Social Difference, and Redemption 111 Redemption and Difference 117 Gender and Competition 120 Beyond the Telos: Rachel 129 Another Aesthetics of Competition: Dance Your Ass Off 133 ! IV. -

Healthism and Fat Politics in TLC's My Big Fat Fabulous Life

Repositorium für die Geschlechterforschung “I Wanna Be Fat” : Healthism and Fat Politics in TLC’s My Big Fat Fabulous Life Kindinger, Evangelia 2017 https://doi.org/10.25595/1555 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kindinger, Evangelia: “I Wanna Be Fat” : Healthism and Fat Politics in TLC’s My Big Fat Fabulous Life, in: FKW : Zeitschrift für Geschlechterforschung und visuelle Kultur (2017) Nr. 62, 48-60. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25595/1555. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY NC ND 4.0 Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY NC ND 4.0 (Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitung) zur License (Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivates). For more Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie information see: hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode.de www.genderopen.de // Evangelia Kindinger “I WANNA BE FAT”: HEALTHISM AND FAT POLITICS IN TLC’S MY BIG FAT FABULOUS LIFE “I wanna be fat.” – This sentence uttered by Whitney Thore, the 1) protagonist of TLC’s My Big Fat Fabulous Life (2015–), in the third Onwards cited as MBFFL. In Germany, the series is broadcasted as Whitney! season’s premiere episode is astonishing because, as the public is – Voll im Leben. lectured time and again by media, medical doctors and other so 2) called health professionals, nobody wants to be (or should be) fat. Cf.: http://www.nobodyshame.com Thore’s declaration becomes even more conspicuous considering (January 2017) its context, namely a reality TV program. -

Dc5m United States Music in English Created at 2016-12-08

Announcement DC5m United States music in english 42 articles, created at 2016-12-08 11:14 articles set mostly positive rate 6.0 1 3.0 'Hairspray Live!' has infectious beat on NBC Since NBC revived the live musical, the irony has been that lesser shows sometimes (7.99/8) meet the demands of leaping to this considerably different medium more successfully. 2016-12-08 01:02 3KB rss.cnn.com 2 0.9 Remembering the Oakland Ghost Ship fire victims 'You don't forget people like that' (7.99/8) The stories of the victims of the Ghost Ship warehouse fire extend beyond their work. Kiyomi Tanouye was a music manager at Shazam and friends say she was much more: 'open and willing,' and 'absolutely inspiring.' 2016-12-08 00:20 2KB abc7news.com 3 0.0 Review: ‘Hairspray Live!’ Had Power Voices but Still Lacked Power (6.67/8) The latest live musical from NBC sabotaged itself with distracting side business. 2016-12-08 01:17 3KB www.nytimes.com 4 2.7 People are seeing horns on Donald Trump's TIME cover (3.20/8) If you weren’t a fan of Donald Trump being named as TIME’s Person of the Year, you weren’t alone—and it seems like some staffers at the magazine weren’t either. 2016-12-08 02:38 1KB www.independent.ie 5 2.4 Sia announces she and husband Erik Anders Lang have split after just over two years of marriage (3.14/8) Australian singer Sia has announced she has split with her husband of two years years, Erik Anders Lang 2016-12-07 19:10 3KB www.dailymail.co.uk 6 0.4 Jennifer Hudson leaves cast in tears with racial equality anthem I Know Where I've Been on Hairspray Live! (2.16/8) The 35-year-old singer appeared to leave some of her cast mates in tears with a stunning performance on Wednesday during NBC's spectacular Hairspray Live!. -

Wednesday Morning, March 28

WEDNESDAY MORNING, MARCH 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View 50 Cent; Vera Wang; Live! With Kelly Jessica Biel; Abi- 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Bone Hampton. (cc) (TV14) gail Breslin. (N) (cc) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today The Hiring Our Heroes Today initiative. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Gina teaches Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Marco about Spanish. (cc) (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent An ear 12/KPTV 12 12 surgeon’s murder. (TV14) International Fel- Paid Paid Paid Zula Patrol (cc) Pearlie (TVY7) Through the Bible International Fel- Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 lowship (TVY) lowship Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Winning With 360 Degree Life Pro-Claim Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) Wisdom (cc) Scenes (cc) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TVPG) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (cc) Divorce Court (N) Excused (cc) Excused (cc) Cheaters (cc) Cheaters (cc) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (TVG) (TVPG) (TV14) (TV14) (TV14) (TV14) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Hunter (cc) (TVPG) Dog the Bounty Hunter (cc) (TVPG) Criminal Minds Mayhem. -

Harrells Man Killed After Crash

Swinging into action Remember, act, educate, spread the word SCC Foundation gears up for annual golf tourney, National Breast Cancer Awareness Month Page A6 THE SAMPSON INDE www.clintonnc.comPENDENT 50 cents F Vol. LXXXVII; Issue 201 Tuesday, October 11, 2011 Clinton, North Carolina F 12 pages Harrells man killed after crash Speed a factor in tragic accident By DOUG CLARK Willie Floyd Crumpler, 45, of was driving along Cannady Road early the crash was 75 mph, a factor, the Tomahawk Highway, Harrells, was Sunday morning when he came around report noted, in the accident. Assistant Editor killed after being ejected from his a curve too fast and struck a concrete Crumpler, it was noted, died at the A 45-year-old Harrells man became 1995 Lexus just 6.7 miles west of driveway culvert. The Lexus flipped scene. the 14th person killed on Sampson Harrells, on Cannady Road, around several times, eventually ejecting No other injuries were reported. County roadways this year when he 1:40 a.m., according to reports by N.C. Crumpler, who was not wearing a seat To reach Doug Clark call 910-592- lost control of his vehicle in a one-car Highway Patrol trooper R.S. Smith. belt. 8137 ext. 123 or email to sisports@ accident Sunday. Those reports note that Crumpler His estimated speed at the time of heartlandpublications.com. Sex case Hobbton cookbook Fugitive heads to featured in state magazine caught court in R’boro By DOUG CLARK this week Assistant Editor By DOUG CLARK A routine traffic stop in Roseboro Assistant Editor has led to the apprehension of a fugi- tive wanted on outstanding fraud and The case of a drug charges by the state of Maryland. -

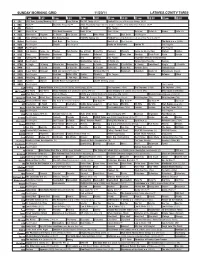

Sunday Morning Grid 11/20/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/20/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2011 Presidents Cup Final Day. Singles matches. From Melbourne, Australia. (N) Å 5 CW News Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. Heroes Vista L.A. 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Tampa Bay Buccaneers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program The Hoax ››› (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Home for Christy Rost Kitchen Kitchen 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Paid Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) Aurora Valle Presenta... Vecinos 40 KTBN K. Hagin Ed Young Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.