Assonance-No.17-January-2017-.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thiruvananthapuram

Proceedings of the District Collector & Chairperson District Disaster Management Authority Thiruvananthapuram (Present: Dr:NavjotKhosa LAS) 5EARS THEELERATI MAHATHA (Issued u/s 26, 30, 34 of Disaster Management Act-2005) DDMA/01/2020/COVID/H7/CZ-183 Dtd:- 11.06.2021 Sub :COVID 19 SARS-CoV-2 Virus Outbreak Management Declaration of Containment Zones - Directions and Procedures- Orders issued- reg Read )GOMs)No.54/2020/H&FWD published as SRO No.243/2020 dtd 21.03.2020. 2)Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 01.05.2020. S) Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 29.08.2020. 4) G.O(Rt) No. 383/2021/DMD dated 26/04/2021 6)G.O(Rt) No. 391/2021/DMD dated 30/04/2021 )Report from District War room, Trivandrum dated 10/06/2021 ) DDMA decision dated 28/05/2021 8) G.O(Rt) No.455/2021/DMD dated 03/06/2021 9) G.O(Rt) No.459/2021/DMD dated 07/06/2021 WHEREAS, Covid-19, is declared as a global pandemic by the World Health Organisation. The Government of India also declared it as a disaster and announced several measures to mitigate the epidemic. Government of Kerala, has deployed several stringent measures to control the spread of the epidemic. Since strict surveillance is one of the most potent tool to prevent the occurrence of a community spread, the government has directed district administration to take all possible measures to prevent the epidemic. AND SRO WHEREAS, notification issued by Govt of Kerala as Kerala Epidemics Diseases, Covid 19, Regulations 2020 in official gazette stipulates that all possible measures shall be incorporated to contain the disease. -

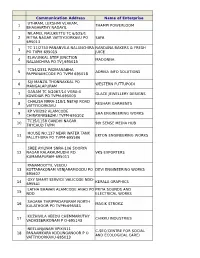

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

Heritage of Kerala

Heritage of Kerala THIRUVANANTHAPURAM 1 of Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Compiled by Department of Town and Country Planning Government of Kerala February 2008 Copies: 3000 © I&PRD Editor in Chief P. Venugopal IAS (Director, Information & Public Relations Department) Co-ordinating Editor P. Abdul Rasheed (Additional Director, Information & Public Relations Department) Deputy Editor in Chief P.S. Suresh (Deputy Director, Information & Public Relations Department) Editor P. R Roy Assist ant Edit ors V.P Pramod Kumar Sunil Hassan Edit orial Assist ance B. Harikumar Design M. Deepak Printed at Akshara Printers Vanchiyoor Thiruvananthapuram 2 PALOLI MOHAMED KUTTY Minister Local Self Government Message Several buildings and precincts exist even now as remnants of Kerala’s cultural tradition and architectural excellence. The value of such buildings and precincts are to be bought to the notice of the general public suitably. Lack of efforts in this regard is the major reason for the increasing trend in demolishing such buildings. Once a heritage monument is lost it will be an irreparable loss forever. Spoiling the heritage buildings will amount to a crime committed to the posterity. The Kerala State Town and Country Planning Department has made an attempt to identify the buildings and precincts having heritage value throughout the State as per the advice of the Art and Heritage Commission. The information gathered from the capital district as part of this is now being released as an initial step. It gives pleasure that the book reveals a number of heritage properties around us, which we are ignorant about. Let this book create awareness among the public regarding some of the existing remnants of the historic, cultural and architectural importance of the district. -

Thiruvananthapuram (Present: Dr.Navjotkhosa IAS) COVID 19 SARS-Cov-2 Virus Outbreak Management

Proceedings of the District Collector & Chairperson Distriet Disaster Management Authority Thiruvananthapuram SKING (Present: Dr.NavjotKhosa IAS) THEMARATA (Issued u's 26, 30, 34 of Disaster Management Act-2005) DDMA/01/2020/COVID/H7/CZ-178 Dtd:-28.05.2021 Sub COVID 19 SARS-CoV-2 Virus Outbreak Management -Declaration of Containment Zones - Directions and Procedures Orders issued - reg. Read 1) GO(Ms)No.54/2020/H&FWD published as SRO No.243/2020 dtd 21.03.2020. 2 Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 01.05.2020. 3)Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 29.08.2020. 4) G.O(Rt) No. 383/2021/DMD dated 26/04/2021 5) G.O(Rt) No. 391/2021/DMD dated 30/04/2021 25/05/2021 & Report from District War room, Trivandrum dated ,23/05/2021, 28/05/2021 7) DDMA decision dated 28/05/2021 8) Govt. Letter No. DMA2-767/2020/DMD Part (2) dated 28.05.2021 *************** Health The WHEREAs, Covid-19, is declared as a global pandemic by the World Organisation. Government of India also declared it as a disaster and announced several measures to mitigate the epidemic. Government of Kerala, has deployed several stringent measures to control the spread of the epidemic. Since strict surveillance is one of the most potent tool to prevent the occurrence of a community spread, the government has directed district administration to take all possible measures to prevent the epidemic. AND WHEREAS, SRO notification issued by Govt of Kerala as Kerala Epidemics Diseases, Covid 19, Regulations 2020 in official gazette stipulates that all possible measures shall be incorporated to contain the disease. -

Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project

Government of Kerala Local Self Government Department Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project (PPTA 4106 – IND) FINAL REPORT VOLUME 2 - CITY REPORT THIRUVANANTHAPURAM MAY 2005 COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of ADB & Government of Kerala. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of either ADB or Government of Kerala constitutes an infringement of copyright. TA 4106 –IND: Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project Project Preparation FINAL REPORT VOLUME 2 – CITY REPORT THIRUVANANTHAPURAM Contents 1. BACKGROUND AND SCOPE 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Project Goal and Objectives 1 1.3 Study Outputs 1 1.4 Scope of the Report 1 2. CITY CONTEXT 2 2.1 Geography and Climate 2 2.2 Population Trends and Urbanization 2 2.3 Economic Development 5 2.3.1 Sectoral Growth 5 2.3.2 Industrial Development 6 2.3.3 Tourism Growth and Potential 7 2.3.4 Growth Trends and Projections 7 3. SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE 8 3.1 Introduction 8 3.2 Household Profile 9 3.2.1 Employment 9 3.2.2 Income and Expenditure 9 3.2.3 Land and Housing 10 3.2.4 Social Capital 10 3.2.5 Health 11 3.2.6 Education 12 3.3 Access to Services 12 3.3.1 Water Supply 12 3.3.2 Sanitation 12 3.3.3 Drainage 13 3.3.4 Solid Waste Disposal 14 3.3.5 Roads, Street Lighting & Access to Public Transport 14 4. POVERTY AND VULNERABILITY 15 4.1 Overview 15 4.1.1 Employment 16 4.1.2 Financial Capital 16 4.1.3 Poverty Alleviation in Thiruvananthapuram 16 5. -

Description of the Property

SKRZ/LD/SARFAESI/ / 2020 Zonal Office, South Kerala AUCTION SALE NOTICE Auction Sale Notice for sale of immovable Assets under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of security Interest Act, 2002 read with proviso to Rule 8 (6) of the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules 2002. Notice is given to the public in general and in particular to the Borrower and guarantors that the below described immovable property mortgaged/charged to the Secured Creditor, the physical possession of which has been taken by the Authorized Officer of CSB Bank Ltd,(Formerly The Catholic Syrian Bank Ltd), Secured Creditor, will be sold on “As is where is” “As is what is” on 11.09.2020 for recovery of Rs.6,89,84,057/37 (Rupees Six Crore Eighty Nine Lakh Eighty Four Thousand and Fifty Seven and Paisa Thirty Seven only) as on 31.07.2020 due to CSB Bank Ltd, Secured Creditor, from the borrower M/S Punarjani Institute of Medical Science & Research Pvt.Ltd. AKG Nagar Peroorkada, Thiruvananthapuram 695 005 and the guarantors Dr Satheesh Kumar Director of M/s Punarjani Institute of Medical Science and Research Pvt Ltd, AKG Nagar, Peroorkada, Thiruvananthapuram 695 024,(Residential Address:-TC 29/145(3), Neelambari, Puthen road, Palkulangara, Pettah, Peroorkada, Thiruvananthapuram 695 005), Mr. Sudhi Karothu Rajan, Director of M/s Punarjani Institute of Medical Science and Research Pvt Ltd, AKG Nagar, Peroorkada, Thiruvananthapuram 695 005(Residential Address:- 49/3K, Balabhadradevi Temple Road, Elamakkara PO, Perandoor, Ernakulam 682 026) Mr.Hrishikesh Ravikumaran Thampi, Director of M/s Punarjani Institute of Medical Science and Research Pvt Ltd, A K G Nagar, Peroorkada, Thiruvananthapuram 695 005 (Residential address:-397/1, (73/396),Elanjickal, 36Perunthanni, Thiruvananthapuram – 695008), Dr Suresh, S/o Krishna Pillai, 36/398(1), Deva Kripa, Askhara Veedhi, Palkulangara, Perunthanni, Thiruvananthapuram 695 024 and Dr Sweety Suresh, W/o Dr Suresh, 36/398(1), Deva Kripa,Akshara Veedhi, Palkulangara,Perunthanni, Thiruvanathapuram - 695 024. -

List of Books in Collection

Book Author Category Biju's remarks Vishishtaaharam Abdullah, Ummi Cookery dishes Nerchakkozhi Abraham, John Stories maverick film maker Daivavela Abraham, Vinu Stories journalist and writer Nashtanayika Abraham, Vinu Novel based on the life of Rosie, Malayalam cinema's first heroine Srinivasan Oru Pusthakam Abraham, Vinu (ed) Film tributes to Malayalam film personality Srinivasan Irakal Vettayadappedumpol Achuthanandan V.S Essay former Chief Minister of Kerala Nerinoppam Achuthanandan V.S Essay former Chief Minister of Kerala Samaram Thanne Jeevitham Achuthanandan V.S Autobiographyformer Chief Minister of Kerala Tharippu Achuthsankar Novel set in 19th century Travancore Rashomon Agutagawa, Rayunosuki Stories translated from the Japanese by Rajan Thuvvara Balatkaram Cheyyappedunna Manass Airoor, Johnson Essay critical study of society's psychology frauds Bhakthiyum Kamavum Airoor, Johnson Essay a rationalist study into religions and their sexual motifs Hypnotism Oru Padanam Airoor, Johnson Essay rationalist and hypnotist on the science, illustrated with case studies Ormakkurippukal Ajitha Autobiographyformer Naxalite leader Aallkkoottam Anand Novel Vayalar Award winning writer Govardhanante Yatrakal Anand Novel a foray into mythology and history Marubhoomikal Undakunnath Anand Novel Vayalar Award winning work Agnisakshi Antharjanam, Lalithambika Novel made into a film by Syamaprasad Ormakallude Kudamaatom Anthicad, Sathyan Film autobiographical work of the filmmaker Sesham Vellithirayil Anthicad, Sathyan Autobiographybehind the scenes -

Educational Environment and Employability Skills

REVIEW OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Peer Refereed Research Journal ISSN 0974-9004 Vol. XIX No. 2 April 2018 Special Issue Published on 1st April, 2018 CONTENTS Editorial Higher Education Commission of India (HECI) Bill 2018 3 1 Hassan J Madrasa Education in Southern Kerala: Novel Strategies and Recommendations to Modernize the System 5 2 Sanitha K K Educational Environment and Employability Skills: An Empirical Study 12 3 Suresh J Problems of Diplomatic Continuity and Change: Inter-State Relations of Travancore and Cochin 23 4 Vijaya S. Uthaman Akshaya E-Kendras: Bridging the Digital Divide 32 5 Hareendrakumar VR Bridging the Gap between Perception and Practice for better Performance: The Real Challenge of Human Resource Manager 41 6 Vishnu K.P Talent Management practices in Taj Hotels 49 7 Abdolhamid Ata & Improving the Business Value Using Cloud Dr. S.Ajitha Computing As a Strategic Tool 58 8 Bitha S. Mani A Review on the Role of Succession Planning in Talent Management Practices in Corporate Environment. 69 9 Devi Priya, Dr. M Sivaraman Leadership Styles and Effectiveness of Managers & Riyas K Basheer in Kerala State Electronics Development Corporation Limited 77 10. Sanitha K K & Quality of Work Life: An empirical Study among Retty R Nath Workers in Printing Industry 89 11 Soumya R S The Bygone Days of Road Transport System in Travancore 101 12 Prakasan P Women in Society: The Gandhian Perspective 107 13 Reeja R Annie Mascarene: A Saga of unsung sacrifice 115 14 S.Sreekala Devi The Education for Independent India Envisioned by Indian Thinkers 125 REVIEW OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Review of Social Sciences is a Bi-annual peer refereed research journal published in January and July every year. -

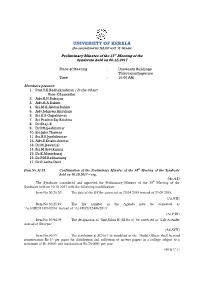

To Download Chalan on 07.09.2017, the Next Working Day, but the Same Was Not Possible As the Site Was Closed and Hence Could Not Remit the Amount

• UNIVERSITY OF KERALA (Re-accredited by NAAC with ‘A’ Grade) Preliminary Minutes of the 31 st Meeting of the Syndicate held on 06.12.2017 Place of Meeting : University Buildings Thiruvananthapuram Time : 10.00 AM Members present: 1. Prof.P.K.Radhakrishnan ( In the Chair) Vice–Chancellor 2. Adv.K.H.Babujan 3. Adv.A.A.Rahim 4. Sri.M.K.Abdul Rahim 5. Adv.Johnson Abraham 6. Sri.K.S.Gopakumar 7. Sri.Prathin Saj Krishna 8. Dr.Shaji.K 9. Dr.P.Rajeshkumar 10. Sri.John Thomas 11. Sri.B.S.Jyothikumar 12. Adv.S.Krishnakumar 13. Dr.M.Jeevanlal 14. Sri.M.Sreekumar 15. Dr.K.Manickaraj 16. Dr.P.M.Radhamany 17. Dr.R.Latha Devi Item No.31.01 Confirmation of the Preliminary Minutes of the 30 th Meeting of the Syndicate held on 10.10.2017 – reg. (Ac.A.I) The Syndicate considered and approved the Preliminary Minutes of the 30 th Meeting of the Syndicate held on 10.10.2017 with the following modification: Item No.30.25.20 The date of the G.O be corrected as 20.04.2015 instead of 23.09.2015. (Ac.F.II) Item No.30.25.49 The file number in the Agenda note be corrected as ‘Ac.FIII/2/16396/2016’ instead of ‘Ac.FIII/2/12406/2013’. (Ac.F.III) Item No.30.94.09 The designation of ‘Smt.Salini B (Sl.No.6)’ be corrected as ‘Lab Attender instead of Sweeper’. (Ad.AVII) Item No.30.95 The resolution at Sl.No.9 be modified as the ‘Nodal Officer shall be paid remuneration Re.1/- per paper for distribution and collection of answer papers in a college subject to a minimum of Rs.1000/- and maximum of Rs.25,000/- per year’. -

An Archaeological Investigation Into Shukasandesham, Unnuneelisandesham and Mediaeval Malayalam Literary Works

An Archaeological Investigation into Shukasandesham, Unnuneelisandesham and Mediaeval Malayalam Literary Works Mohammed Muhaseen B. S.1, Ajit Kumar1, Vinuraj B.1 and Reni P. Joseph1 1. Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom Campus, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 581, Kerala, India (Email: muhasin.muhammed9@ gmail.com, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]) Received: 25 September 2018; Revised: 17 October 2018; Accepted: 14 November 2018 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 6 (2018): 739‐755 Abstract: This article is a prelimenary archaeological investigation into the mediaeval Sandeshakavyas or poetic works namely Shukasandesham, Unnuneelisandesham and Manipravalam chambukavyas. Shukasandesham and Unnuneelisandesham elaborately describes the social, cultural, economic and transport modes etc., in southern Kerala during 13th‐14th century CE. The problem oriented archaeological explorations were undertaken along the route traversed by the protagonists in the Sandeshakavyas to verify its authenticity and document archaeological sites and cultural remains along the way. Keywords: Shukasandesham, Unnuneelisandesham, Southern Kerala, Economy, Transportation, Foreign Trade, Kollam Port Introduction In Kerala, the mediaeval literary tradition has a strong foundation. Mushikavamsa of Atula dated to 11th century CE is said to be the earliest from the region. This work written in Sanskrit speaks of the legend and succession of Mushika dynasty from northern Kerala. Ramacharitam, written in 12th century CE belonging to Paattu school (folklore ballads) was written using Tamil language (Menon1978:191). The first Sandeshakavya (message poem) composed in Kerala was Shukasandesham written during the 13th century CE. From the beginning of 14th century CE, a new form of literary tradition emerged in Kerala known as Manipravalam. The compositions in Manipravalam literature used a mixture of Sanskrit and early Malayalam. -

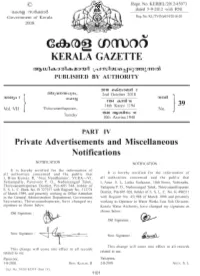

Change Name.Pdf

2nd OCT. 2018] KERALA GAZETTE 1420 NOTIFICATION NOTIFICATION It is hereby notified for the information of all It is hereby notified for the information of all authorities concerned and the public that I, Vargheese. A, authorities concerned and the public that I, Dally . R, Malanchuttu Harijan Colony , Parasuvaikkal P . O., Ambalathuvilakam Veedu, Karamoodu, Vellarada P. O., Neyyattinkara Taluk, Thiruvananthapuram District, Neyyattinkara Taluk, Thiruvananthapuram District, Pin-695 508, holder of Extract of School Admission Pin-695 505, holder of Extract of School Admission Register with Admission No. 1424, date of Admission Register with Admission No. 7893, date of Admission 3-5-1970, issued from S t. John’s H. S. S., Undancode, also 25-5-1981, issued from V. P. M. H. S. Vellarada; Ration Card known as Varghees. E in the Birth Certificate with No. 1106111284 (Sl. No. 1), dated 15-3-2017, issued by the Registration No. 36400/2006, date of Registration Taluk Supply Of ficer, Neyyattinkara, also known as Dolly 8-12-2006, issued from Corporation of Thiruvananthapuram, in the Electoral Identity Card No. KKL1239797, dated of my son Akhish. V, known as Vargheese in the Birth 31-8-2000, issued by the Electoral Registration Of ficer, Certificate with Registration No. 16106/2003, date of Neyyattinkara LA Constituency; Marriage Certificate Registration 30-12-2003, issued from Corporation of No. 2409, issued from South Kerala Diocese, Church of Thiruvananthapuram, of my son Adarsh. V, known as South India, and known as Dally Mani in the Passport Varghese in the Electoral Identity Card No. BRP1585975, No. K7835352, dated 18-1-2013, issued from Passport dated 26-5-2003, issued by the Electoral Registration Office, Thiruvananthapuram, is one and the same person.