The Geography of Ptolemy Elucidated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Genetic Context for Understanding the Trigonometric Functions Danny Otero Xavier University, [email protected]

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Pre-calculus and Trigonometry Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) Spring 3-2017 A Genetic Context for Understanding the Trigonometric Functions Danny Otero Xavier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_precalc Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Otero, Danny, "A Genetic Context for Understanding the Trigonometric Functions" (2017). Pre-calculus and Trigonometry. 1. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_precalc/1 This Course Materials is brought to you for free and open access by the Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pre-calculus and Trigonometry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Genetic Context for Understanding the Trigonometric Functions Daniel E. Otero∗ July 22, 2019 Trigonometry is concerned with the measurements of angles about a central point (or of arcs of circles centered at that point) and quantities, geometrical and otherwise, that depend on the sizes of such angles (or the lengths of the corresponding arcs). It is one of those subjects that has become a standard part of the toolbox of every scientist and applied mathematician. It is the goal of this project to impart to students some of the story of where and how its central ideas first emerged, in an attempt to provide context for a modern study of this mathematical theory. -

If 1+1=2 Then the Pythagorean Theorem Holds, Or One More Proof of the Oldest Theorem of Mathematics

!"#$%"&"!'()**#%"$'+&'%,#'`.#%/)'01"+/P'3$"4#/5"%6'+&'7/9)'0)/#2 Vol. 10 (XXVII) no. 1, 2013 ISSN-L 1841-9267 (Print), ISSN 2285-438X (Online), ISSN 2286-3184 (CD-ROM) If 1+1=2 then the Pythagorean theorem holds, or one more proof of the oldest theorem of mathematics Alexandru HORVATH´ ”Petru Maior” University of Tg. Mures¸, Romania e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Pythagorean theorem is one of the oldest theorems of mathematics. It gained dur- ing the time a central position and even today it continues to be a source of inspiration. In this note we try to give a proof which is based on a hopefully new approach. Our treatment will be as intuitive as it can be. Keywords: Pythagorean theorem, geometric transformation, Euclidean geometry MSC 2000: 51M04, 51M05, 51N20 One of the oldest theorems of mathematics – the T T Pythagorean theorem – states that the area of the square drawn on the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) of a right angled triangle, is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares constructed on the other two sides, (the catheti). That is, 2 2 2 a + b = c , if we denote the length of the sides of the triangle by a, b, c respectively. Figure 1. The transformation Loomis ([3]) collected several hundreds of different proofs of this theorem, and classified them in categories. Maor ([4]) traces the evolution of the Pythagorean theorem and its impact on mathematics and on our culture in gen- Let us assume T is such a transformation having a as the eral. -

The Geography of Ptolemy Elucidated

The Grography of Ptolemy The geography of Ptolemy elucidated Thomas Glazebrook Rylands 1893 • A brief outline of the rise and progress of geographical inquiry prior to the time of Ptolemy. §1.—Introductory. IN tracing the early progress of Geography it is necessary to remember that, like all other sciences, it arose from “ small beginnings.” When men began to move from place to place they naturally desired to tell the tale of their wanderings, both for their own satisfaction and for the information of others. Such accounts have now perished, but their results remain in the earliest records extant ; hence, it is impossible to begin an investigation into the history of Geography at the true fountain-head, though it is in some instances possible to guess the nature of the source from the character of the resultant stream. A further difficulty lies in the question as to where the science of Geography begins. A Greek would probably have answered when some discoverer first invented a method for map- ping out the distance between certain places, which distance conversely could be ascertained directly from the map. In accordance with modern method, the science of Geography might be said to begin when the subject ceased to be dealt with mythically or dogmatically ; when facts were collected and reduced to laws, while these laws again, or their prior facts, were connected with other laws—in the case of Geography with those of Mathematics and Astro- nomy. Perhaps it would be better to follow the latter principle of division, and consequently the history of Geography may be divided into two main stages—“ Pre-Scientific” and Scientific Geography—though strictly speaking, the name of Geography should be applied to the latter alone. -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

Our Place in the Universe Sun Kwok

Our Place in the Universe Sun Kwok Our Place in the Universe Understanding Fundamental Astronomy from Ancient Discoveries Second Edition Sun Kwok Faculty of Science The University of Hong Kong Hong Kong, China This book is a second edition of the book “Our Place in the Universe” previously published by the author as a Kindle book under amazon.com. ISBN 978-3-319-54171-6 ISBN 978-3-319-54172-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-54172-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937904 © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Early & Rare World Maps, Atlases & Rare Books

19219a_cover.qxp:Layout 1 5/10/11 12:48 AM Page 1 EARLY & RARE WORLD MAPS, ATLASES & RARE BOOKS Mainly from a Private Collection MARTAYAN LAN CATALOGUE 70 EAST 55TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10022 45 To Order or Inquire: Telephone: 800-423-3741 or 212-308-0018 Fax: 212-308-0074 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.martayanlan.com Gallery Hours: Monday through Friday 9:30 to 5:30 Saturday and Evening Hours by Appointment. We welcome any questions you might have regarding items in the catalogue. Please let us know of specific items you are seeking. We are also happy to discuss with you any aspect of map collecting. Robert Augustyn Richard Lan Seyla Martayan James Roy Terms of Sale: All items are sent subject to approval and can be returned for any reason within a week of receipt. All items are original engrav- ings, woodcuts or manuscripts and guaranteed as described. New York State residents add 8.875 % sales tax. Personal checks, Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and wire transfers are accepted. To receive periodic updates of recent acquisitions, please contact us or register on our website. Catalogue 45 Important World Maps, Atlases & Geographic Books Mainly from a Private Collection the heron tower 70 east 55th street new york, new york 10022 Contents Item 1. Isidore of Seville, 1472 p. 4 Item 2. C. Ptolemy, 1478 p. 7 Item 3. Pomponius Mela, 1482 p. 9 Item 4. Mer des hystoires, 1491 p. 11 Item 5. H. Schedel, 1493, Nuremberg Chronicle p. 14 Item 6. Bergomensis, 1502, Supplementum Chronicum p. -

9 · the Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece

9 · The Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece PREPARED BY THE EDITORS FROM MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY GERMAINE AUJAe There is no complete break between the development of That such a change should occur is due both to po cartography in classical and in Hellenistic Greece. In litical and military factors and to cultural developments contrast to many periods in the ancient and medieval within Greek society as a whole. With respect to the world, we are able to reconstruct throughout the Greek latter, we can see how Greek cartography started to be period-and indeed into the Roman-a continuum in influenced by a new infrastructure for learning that had cartographic thought and practice. Certainly the a profound effect on the growth of formalized know achievements of the third century B.C. in Alexandria had ledge in general. Of particular importance for the history been prepared for and made possible by the scientific of the map was the growth of Alexandria as a major progress of the fourth century. Eudoxus, as we have seen, center of learning, far surpassing in this respect the had already formulated the geocentric hypothesis in Macedonian court at Pella. It was at Alexandria that mathematical models; and he had also translated his Euclid's famous school of geometry flourished in the concepts into celestial globes that may be regarded as reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 B.C.). And it anticipating the sphairopoiia. 1 By the beginning of the was at Alexandria that this Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy I Hellenistic period there had been developed not only the Soter, a companion of Alexander, had founded the li various celestial globes, but also systems of concentric brary, soon to become famous throughout the Mediter spheres, together with maps of the inhabited world that ranean world. -

10 · Greek Cartography in the Early Roman World

10 · Greek Cartography in the Early Roman World PREPARED BY THE EDITORS FROM MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY GERMAINE AUJAe The Roman republic offers a good case for continuing to treat the Greek contribution to mapping as a separate CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN THEORETICAL strand in the history ofclassical cartography. While there CARTOGRAPHY: POLYBIUS, CRATES, was a considerable blending-and interdependence-of AND HIPPARCHUS Greek and Roman concepts and skills, the fundamental distinction between the often theoretical nature of the Greek contribution and the increasingly practical uses The extent to which a new generation of scholars in the for maps devised by the Romans forms a familiar but second century B.C. was familiar with the texts, maps, satisfactory division for their respective cartographic in and globes of the Hellenistic period is a clear pointer to fluences. Certainly the political expansion of Rome, an uninterrupted continuity of cartographic knowledge. whose domination was rapidly extending over the Med Such knowledge, relating to both terrestrial and celestial iterranean, did not lead to an eclipse of Greek influence. mapping, had been transmitted through a succession of It is true that after the death of Ptolemy III Euergetes in well-defined master-pupil relationships, and the pres 221 B.C. a decline in the cultural supremacy of Alex ervation of texts and three-dimensional models had been andria set in. Intellectual life moved to more energetic aided by the growth of libraries. Yet this evidence should centers such as Pergamum, Rhodes, and above all Rome, not be interpreted to suggest that the Greek contribution but this promoted the diffusion and development of to cartography in the early Roman world was merely a Greek knowledge about maps rather than its extinction. -

User Guide 2.0

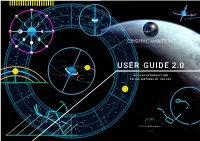

NORTH CELESTIAL POLE Polaris SUN NORTH POLE E Q U A T O R C SOUTH POLE E L R E S T I A L E Q U A T O EARTH’S AXIS EARTH’S SOUTH CELESTIAL POLE USER GUIDE 2.0 WITH AN INTRODUCTION 23.45° TO THE MOTIONS OF THE SKY meridian E horizon W rise set Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics 2019 II III Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics FULLSCREEN CONTENTS SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS VI SKY SETTINGS 24 CONSTELLATIONS 24 HELP MENU INTRODUCTION 1 ZODIAC 24 BASIC CONCEPTS 2 CONSTELLATION NAMES 24 CENTRED ON EARTH 2 WORLD CLOCKASTRONOMYASTROLOGY MINIMAL STAR NAMES 25 SEARCH LOCATIONS THE CELESTIAL SPHERE IS LONG EXPOSURE 25 A PROJECTION 2 00:00 INTERSTELLAR GAS & DUST 25 A FIRST TOUR 3 EVENTS & SKY GRADIENT 25 PRESETS NOTIFICATIONS LOOK AROUND, ZOOM IN AND OUT 3 GUIDES 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS ON THE GLOBE 4 HORIZON 26 CENTER YOUR VIEW 4 SKY EARTH SOLAR PLANET NAMES 26 SYSTEM ABOUT & INFO FULLSCREEN 4 CONNECTIONS 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 5 CELESTIAL RINGS 27 ADVANCED SETTINGS FAVOURITES 5 EQUATORIAL COORDINATES 27 QUICK START QUICK VIEW OPTIONS 6 FAVOURITE LOCATIONS ORBITS 27 VIEW THE USER INTERFACE 7 EARTH SETTINGS 28 GEOCENTRIC HOW TO EXIT 7 CLOUDS 28 SCREENSHOT PRESETS 8 HI -RES 28 POSITION 28 HELIOCENTRIC WORLD CLOCK 9 COMPASS CELESTIAL SPHERE SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 10 THE MOON 29 FAVOURITES 10 EVENTS & NOTIFICATIONS 30 ASTRONOMY MODE 15 SETTINGS 31 VISUAL SETTINGS ASTROLOGY MODE 16 SYSTEM NOTIFICATIONS 31 IN APP NOTIFICATIONS 31 MINIMAL MODE 17 ABOUT 32 THE VIEWS 18 ADVANCED SETTINGS 32 SKY VIEW 18 COMPASS ON / OFF 19 ASTRONOMICAL ALGORITHMS 33 EARTH VIEW 20 SCREENSHOT 34 CELESTIAL SPHERE ON / OFF 20 HELP 35 TIME CONTROL SOLAR SYSTEM VIEW 21 FINAL THOUGHTS 35 GEOCENTRIC / HELIOCENTRIC 21 TROUBLESHOOTING 36 VISUAL SETTINGS 22 CONTACT 37 CLOCK SETTINGS 22 ASTRONOMICAL CONCEPTS 38 ECLIPTIC CLOCK FACE 22 EQUATORIAL CLOCK FACE 23 IV V INTRODUCTION SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS The Cosmic Watch is a virtual planetarium on your mobile device. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] [Taprobana] Duodecima Asie Tabula Stock#: 58553 Map Maker: Ptolemy / Reger Date: 1486 Place: Ulm Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG+ Size: 21 x 14.5 inches Price: $ 7,500.00 Description: Sri Lanka, As Known To The Greeks Fine old color example of this remarkable early map of Taprobana (Sri Lanka), from the 1486 Ulm edition of Ptolemy's Geographia. The map is drawn from the work of Nicolas Germanicus, whose manuscript maps were created to illustrate pre-1470 editions of Ptolemy's Geographia. The present map is from the second edition of this work, which was first published in 1482. Taprobana The earliest recorded note of Taprobana dates to before the time of Alexander the Great as inferred from Pliny. The treatise De Mundo (supposedly by Aristotle, but according to others by Chrysippus the Stoic (280 to 208 BC)) described an island the size of Great Britain. The name Taprobana seems to date to the Greek geographer Megasthenes around 290 BC. Eratosthenes (276 to 196 BC) references Taprobana in his Geographia. Ptolemy (139 AD) incorporates Taprobana in his geographical treatise, identifying it as a relatively large island south of continental Asia. Taprobana was the home of the legendary single giant footed man-like creatures. G.U. Pope, in his book "Textbook of Indian History", claims the name to be derived from Dipu-Ravana, meaning the island of Ravana. Drawer Ref: India 2 Stock#: 58553 Page 1 of 3 Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. -

Spices in Maps. Fifth Centenary of the First Circumnavigation of the World

e-Perimetron, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2020 [57-81] www.e-perimetron.org | ISSN 1790-3769 Marcos Pavo López∗ Spices in maps. Fifth centenary of the first circumnavigation of the world Keywords: Spices, circumnavigation, centenary, Magellan, Elcano Summary: The first circumnavigation of the world, promoted and initially commanded by Ferdinand Magellan and finished under Juan Sebastian Elcano’s command, is considered the greatest feat in the history of explorations. The fifth centenary of this voyage (1519-1522) has brought again into light the true objective of the expedition: to reach the Spice Islands, the source of some of the most expensive goods in the sixteenth century. The interest on spices can be traced back to several centuries BC. For ancient and medieval Europeans, the spices would come from unknown and mysterious places in the East. The history of cartography until the sixteenth century is closely related to how the semi-mythical Spice Islands were represented in maps. This paper tries to show the progressive appearance of the sources of spices in maps: from the first references in Ptolemy or the imprecise representation in Fra Mauro’s or Martin Behaim’s cartography, to the well-known location of the clove islands in Portuguese nautical charts and, finally, in the Spanish Padrón Real. 1. The first circumnavigation of the world and the purpose behind it When the ship Victoria, carrying on board eighteenth exhausted crewmembers and at least three natives from the Moluccas, arrived in Sanlúcar de Barrameda on 6 September 1522 under the command of the Guipuscoan Juan Sebastián Elcano, almost three years had passed since its departure along with other four ships (Trinidad, Concepción, San Antonio and Santiago), from Sanlúcar port on 20 September 1519 ‒the official departure took place, however, in Seville on 10 August‒. -

Armillary Sphere

Armillary Sphere Inventory no. 45453 Armillary sphere Armillary sphere for demonstration of the heavenly spheres made and signed by Carlo Plato, Rome, c.1588. The armillary sphere is an instrument that extends right back to the ancients, and was certainly in used by the second-century astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy, of Alexandria. It was a mathematical instrument designed to demonstrate the movement of the celestial sphere about a stationary Earth at its centre. The concept of the celestial sphere was fundamental to astronomy from Antiquity through the Middle Ages and into the Early-Modern era. At the centre of the sphere is the Earth. As the Earth is stationary in this model, it is the celestial sphere which rotates about it and acts as a reference system for locating the celestial bodies – stars, in particular – from a geocentric perspective. The instrument survived throughout the medieval period into the early modern era, and in many respects came to symbolise the queen of the sciences, astronomy. It wasn’t until the middle of the sixteenth-century that the basis of the instrument – a geocentric concept of the Universe – was seriously challenged by the Polish mathematician, Nicolaus Copernicus. Even then, the instrument still continued to serve a useful purpose as a purely mathematical instrument. Portrait of Nicolas Copernicus 1580 Held stationary at the centre is a small brass sphere representing the Earth. About it rotate a set of rings representing the heavens – the celestial sphere – one complete revolution approximating to a day or 24 hours. The sphere is mounted at the celestial poles which define the axis of rotation, and its structure includes an equatorial ring and, parallel to this, above and below, two smaller rings representing the Tropic of Cancer to the north, and the Tropic of Capricorn to the south.