Submarines and Peacekeeping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Forces' Wear of Non-Standard Uniforms*

Special Forces’ Wear of Non-Standard Uniforms* W. Hays Parks** In February 2002, newspapers in the United States and United Kingdom published complaints by some nongovernmental organizations (“NGOs”) about US and other Coalition special operations forces operating in Afghanistan in “civilian clothing.”1 The reports sparked debate within the NGO community and among military judge advocates about the legality of such actions.2 At the US Special Operations Command (“USSOCOM”) annual Legal Conference, May 13–17, 2002, the judge advocate debate became intense. While some attendees raised questions of “illegality” and the right or obligation of special operations forces to refuse an “illegal order” to wear “civilian clothing,” others urged caution.3 The discussion was unclassified, and many in the room were not * Copyright © 2003 W. Hays Parks. ** Law of War Chair, Office of General Counsel, Department of Defense; Special Assistant for Law of War Matters to The Judge Advocate General of the Army, 1979–2003; Stockton Chair of International Law, Naval War College, 1984–1985; Colonel, US Marine Corps Reserve (Retired); Adjunct Professor of International Law, Washington College of Law, American University, Washington, DC. The views expressed herein are the personal views of the author and do not necessarily reflect an official position of the Department of Defense or any other agency of the United States government. The author is indebted to Professor Jack L. Goldsmith for his advice and assistance during the research and writing of this article. 1 See, for example, Michelle Kelly and Morten Rostrup, Identify Yourselves: Coalition Soldiers in Afghanistan Are Endangering Aid Workers, Guardian (London) 19 (Feb 1, 2002). -

Unlocking NATO's Amphibious Potential

November 2020 Perspective EXPERT INSIGHTS ON A TIMELY POLICY ISSUE J.D. WILLIAMS, GENE GERMANOVICH, STEPHEN WEBBER, GABRIELLE TARINI Unlocking NATO’s Amphibious Potential Lessons from the Past, Insights for the Future orth Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members maintain amphibious capabilities that provide versatile and responsive forces for crisis response and national defense. These forces are routinely employed in maritime Nsecurity, noncombatant evacuation operations (NEO), counterterrorism, stability operations, and other missions. In addition to U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) and U.S. Navy forces, the Alliance’s amphibious forces include large ships and associated landing forces from five nations: France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK). Each of these European allies—soon to be joined by Turkey—can conduct brigade-level operations, and smaller elements typically are held at high readiness for immediate response.1 These forces have been busy. Recent exercises and operations have spanned the littorals of West and North Africa, the Levant, the Gulf of Aden and Arabian Sea, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. Given NATO’s ongoing concerns over Russia’s military posture and malign behavior, allies with amphibious capabilities have also been exploring how these forces could contribute to deterrence or, if needed, be employed as part of a C O R P O R A T I O N combined and joint force in a conflict against a highly some respects, NATO’s ongoing efforts harken back to the capable nation-state. Since 2018, NATO’s headquarters Cold War, when NATO’s amphibious forces routinely exer- and various commands have undertaken initiatives and cised in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic as part of a convened working groups to advance the political intent broader strategy to deter Soviet aggression. -

On Strategy: a Primer Edited by Nathan K. Finney

Cover design by Dale E. Cordes, Army University Press On Strategy: A Primer Edited by Nathan K. Finney Combat Studies Institute Press Fort Leavenworth, Kansas An imprint of The Army University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Finney, Nathan K., editor. | U.S. Army Combined Arms Cen- ter, issuing body. Title: On strategy : a primer / edited by Nathan K. Finney. Other titles: On strategy (U.S. Army Combined Arms Center) Description: Fort Leavenworth, Kansas : Combat Studies Institute Press, US Army Combined Arms Center, 2020. | “An imprint of The Army University Press.” | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2020020512 (print) | LCCN 2020020513 (ebook) | ISBN 9781940804811 (paperback) | ISBN 9781940804811 (Adobe PDF) Subjects: LCSH: Strategy. | Strategy--History. Classification: LCC U162 .O5 2020 (print) | LCC U162 (ebook) | DDC 355.02--dc23 | SUDOC D 110.2:ST 8. LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020512. LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020513. 2020 Combat Studies Institute Press publications cover a wide variety of military topics. The views ex- pressed in this CSI Press publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Depart- ment of the Army or the Department of Defense. A full list of digital CSI Press publications is available at https://www.armyu- press.army.mil/Books/combat-studies-institute. The seal of the Combat Studies Institute authenticates this document as an of- ficial publication of the CSI Press. It is prohibited to use the CSI’s official seal on any republication without the express written permission of the director. Editors Diane R. -

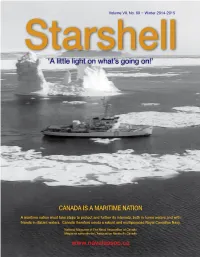

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 69 ~ Winter 2014-2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… To date, the Royal Canadian Navy’s only purpose-built, ice-capable Arctic Patrol Vessel, HMCS Labrador, commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy July 8th, 1954, ‘poses’ in her frozen natural element, date unknown. She was a state-of-the- Starshell art diesel electric icebreaker similar in design to the US Coast Guard’s Wind-class ISSN-1191-1166 icebreakers, however, was modified to include a suite of scientific instruments so it could serve as an exploration vessel rather than a warship like the American Coast National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Guard vessels. She was the first ship to circumnavigate North America when, in Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada 1954, she transited the Northwest Passage and returned to Halifax through the Panama Canal. When DND decided to reduce spending by cancelling the Arctic patrols, Labrador was transferred to the Department of Transport becoming the www.navalassoc.ca CGSS Labrador until being paid off and sold for scrap in 1987. Royal Canadian Navy photo/University of Calgary PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele In this edition… PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] NAC Conference – Canada’s Third Ocean 3 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] The Editor’s Desk 4 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] The Bridge 4 The Front Desk 6 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] NAC Regalia Sales 6 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

Writing to Think

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Newport Papers Special Collections 2-2014 Writing to Think Robert C. Rubel Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers Recommended Citation Rubel, Robert C., "Writing to Think" (2014). Newport Papers. 41. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newport Papers by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 41 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Writing to Think The Intellectual Journey of a Naval Career NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 41 Robert C. Rubel Cover This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Writing to Think The Intellectual Journey of a Naval Career Robert C. Rubel NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS Newport, Rhode Island meyers$:___WIPfrom C 032812:_Newport Papers:_NP_41 Rubel:_InDesign:000 NP_41 Rubel-FrontMatter.indd January 31, 2014 10:06 AM Naval War College The Newport Papers are extended research projects that Newport, Rhode Island the Director, the Dean of Naval Warfare Studies, and the Center for Naval Warfare Studies President of the Naval War College consider of particular Newport Paper Forty-One interest to policy makers, scholars, and analysts. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

Okanagan Nation E-News

S Y I L X OKANAGAN NATION E-NEWS April 2010 Okanagan Nation Jr. Girls Bring Home Provincial Championship Table of Contents HMCS Okanagan 2 Syilx Youth Unity Run 3 Browns Creek 4 Update Child & Family 6 NRLUT Update FN Leaders 7 Denounce Fed Funding Cuts Health Hub 8 Columbia River 9 93,000 Sockeye 10 Released Sturgeon 11 Gathering AA Roundup 12 Photo: Team Mng Lisa Reid, Ashley McGinnis, Dina Brown, Jasmine Reid, Janessa Lambert, Coach Peter Waardenburg, Erica Swan, Jade Waardenburg, Nicola Terbasket, Coach Amanda Montgomery, Kirsten Lindley, Front: Jade Sargent Family 13 Missing Courtney Louie Intervention The Syilx, Okanagan Nation, Jr Girls basketball ball it was stolen by Reid, passed to Sargent and Society Conf ONA Bursary 14 team brought home the Championship and she did a lay in to win the game. Most Sportsmanlike Team after playing 8 R Native Voice 15 “Okanagan girls were full value for the win, University Camp 16 games in Prince Rupert during Spring Break. hard working and all the class in the world.” Fish Lake 17 The final four games were all nail biters, said said Kitimat coach Keith Nyce. What’s Reid; the gym was vibrating with the fans from Happening 18 Other awards included MVP, Jade Toll Free all the villages cheering on their nations. Waardenburg, Best Defense and All Star In the final game against Kitimat there was only 1-866-662-9609 Jasmine Reid, and All Star Ashley McGinnis 9 seconds left, Okanagan down by 2, when Waardenburg drew the foal that would take The Okanagan Nation will host the 2011 Jr All her to the free throw line. -

Ultimate Test of Leadership Under Stress

MILITARY Ultimate test of leadership under stress The Navy’s Perisher submarine command course is celebrating its centenary Ali Kefford April 15 2017 The Times Lieutenant-Commander Dan Simmonds on a Perisher exercise aboard HMS Talent BRAD WAKEFIELD Standing between Russia’s increasingly assertive Northern Fleet submarines and British shores are the Royal Navy submarine captains, deemed the most “feared” in the world by Tom Clancy, the author of The Hunt for Red October. Their reputation is based on the officers’ ability to push a boat and her crew confidently to the very edge of what each is capable of, acting aggressively but without becoming rash or endangering the lives of those on board. These skills are honed on an infamously brutal command course, a century old this year, known within the service as “Perisher”, because the 35 per cent who fail can never serve underwater again, making a decade’s sea preparation redundant. Perisher is knowingly unforgiving; the submarine service’s responsibilities are too complex, perilous and crucial to British defence for it not to be. In addition to keeping the nuclear deterrent on permanent patrol, its other key tasks include the launching of cruise-missile attacks, the planting of boats off enemy shores to soak up intelligence, and covertly deploying the Special Boat Service. Those running the operations must be devoid of fear — and they are. “The underwater world is still very largely impenetrable. And, as long as that remains so, it will dominate the surface of the sea, and the sky above, and the space above that,” says Admiral Sir George Zambellas, the former First Sea Lord. -

100 Years of Submarines in the RCN!

Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ Volume VII, No. 65 ~ Winter 2013-14 Public Archives of Canada 100 years of submarines in the RCN! National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca Please help us put printing and postage costs to more efficient use by opting not to receive a printed copy of Starshell, choosing instead to read the FULL COLOUR PDF e-version posted on our web site at http:www.nava- Winter 2013-14 lassoc.ca/starshell When each issue is posted, a notice will | Starshell be sent to all Branch Presidents asking them to notify their ISSN 1191-1166 members accordingly. You will also find back issues posted there. To opt out of the printed copy in favour of reading National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Starshell the e-Starshell version on our website, please contact the Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada Executive Director at [email protected] today. Thanks! www.navalassoc.ca PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh OUR COVER RCN SUBMARINE CENTENNIAL HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele The two RCN H-Class submarines CH14 and CH15 dressed overall, ca. 1920-22. Built in the US, they were offered to the • RCN by the Admiralty as they were surplus to British needs. PRESIDENT Jim Carruthers, [email protected] See: “100 Years of Submarines in the RCN” beginning on page 4. PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] TREASURER • Derek Greer, [email protected] IN THIS EDITION BOARD MEMBERS • Branch Presidents NAVAL AFFAIRS • Richard Archer, [email protected] 4 100 Years of Submarines in the RCN HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

60 Years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 - 2018 Part 4: Europe & Canada Peter Lobner July 2018 1 Foreword In 2015, I compiled the first edition of this resource document to support a presentation I made in August 2015 to The Lyncean Group of San Diego (www.lynceans.org) commemorating the 60th anniversary of the world’s first “underway on nuclear power” by USS Nautilus on 17 January 1955. That presentation to the Lyncean Group, “60 years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955 – 2015,” was my attempt to tell a complex story, starting from the early origins of the US Navy’s interest in marine nuclear propulsion in 1939, resetting the clock on 17 January 1955 with USS Nautilus’ historic first voyage, and then tracing the development and exploitation of marine nuclear power over the next 60 years in a remarkable variety of military and civilian vessels created by eight nations. In July 2018, I finished a complete update of the resource document and changed the title to, “Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018.” What you have here is Part 4: Europe & Canada. The other parts are: Part 1: Introduction Part 2A: United States - Submarines Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships Part 3A: Russia - Submarines Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications Part 5: China, India, Japan and Other Nations Part 6: Arctic Operations 2 Foreword This resource document was compiled from unclassified, open sources in the public domain. I acknowledge the great amount of work done by others who have published material in print or posted information on the internet pertaining to international marine nuclear propulsion programs, naval and civilian nuclear powered vessels, naval weapons systems, and other marine nuclear applications. -

Lead and Line April

April 2015 volume 3 0 , i s s u e N o . 4 LEAD AND LINE newsletter of the naval Association of canada-vancouver island Buzzed by Russians...again At sea with Victoria Monsters be here Another cocaine bust Page 2 Page 3 Page 9 Page 14 HMCS Victoria Update... Page 3 Speaker: Captain Bill Noon NAC-VI Topic: Update on the Franklin Expedition 27 Apr Cost will be $25 per person. Luncheon Guests - spouses, friends, family are most welcome Please contact Bud Rocheleau [email protected] or Lunch at the Fireside Grill at 1130 for 1215 250-386-3209 prior to noon on Thursday 19 Mar. 4509 West Saanich Road, Royal Oak, Saanich. NPlease advise of any allergies or food sensitivities Ac NACVI • PO box 5221, Victoria BC • Canada V8R 6N4 • www.noavi.ca • Page 1 April 2015 volume 30 , i s s u e N o . 4 NAC-VI LEAD AND LINE Don’t be so wet! There has been a great kerfuffle on Parliament Hill, and in the press, about the possibility that HMCS Fredericton might have been confronted by a Russian warship and buzzed by Russian fighter jets. Not so says NATO, stating that any Russian vessels were on the horizon and the closest any plane got was 69 kilometers. (Our MND says it was within 500 ft!) An SU-24 Fencer circled HMCS Toronto, during NATO op- And so what if they did? It would hardly be surprising, if erations in the Black Sea last September. in a period of some tension (remember the Ukraine) that a Russian might be interested in scoping out the competition And you can’t tell me that the Americans (who were with us or that we might be interested in doing the same in return.