Face Recognition: Primates in the Wild∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Survival of the Central American Squirrel Monkey

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Burghardt, Liana, "The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 435. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/435 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Survival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt Carleton College Fall 2005 Burghardt 2 I dedicate this paper which documents my first scientific adventure in the field to my father. “It is often necessary to put aside the objective measurements favored in controlled laboratory environments and to adopt a more subjective naturalistic viewpoint in order to see pattern and consistency in the rich, varied context of the natural environment” (Baldwin and Baldwin 1971: 48). Acknowledgments This paper has truly been an adventure and as is common I have many people I wish to thank. -

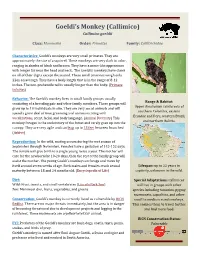

Goeldi's Monkey

Goeldi’s Monkey (Callimico) Callimico goeldii Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Callitrichidae Characteristics: Goeldi’s monkeys are very small primates. They are approximately the size of a squirrel. These monkeys are very dark in color, ranging in shades of black and brown. They have a mane-like appearance with longer fur near the head and neck. The Goeldi’s monkeys have claws on all of their digits except the second. These small primates weigh only 22oz on average. They have a body length that is in the range of 8-12 inches. The non-prehensile tail is usually longer than the body. (Primate Info Net) Behavior: The Goeldi’s monkey lives in small family groups usually consisting of a breeding pair and other family members. These groups will Range & Habitat: Upper Amazonian rainforests of grow up to 10 individuals in size. They are very social animals and will southern Colombia, eastern spend a great deal of time grooming and communicating with Ecuador and Peru, western Brazil, vocalizations, scent, facial, and body language. (Animal Diversity) This and northern Bolivia. monkey forages in the understory of the forest and rarely goes up into the canopy. They are very agile and can leap up to 13 feet between branches! (Arkive) Reproduction: In the wild, mating occurs during the wet season of September through November. Females have a gestation of 145-152 days. The female will give birth to a single young twice a year. The mother will care for the newborn for 10-20 days, then the rest of the family group will assist the mother. -

Capuchins Are the Most Intelligent New World Monkeys – Perhaps As Intelligent As Chimpanzees

Hooded Capuchin Cebus paella cay Capuchin IQ - Capuchins are the most intelligent New World monkeys – perhaps as intelligent as chimpanzees. They are noted for their ability to fashion and use tools. Because of their ability to learn and remember, they were once trained as “organ grinder” monkeys, are often used in movies and have even been trained to assist disabled people with routine tasks around the house. Get a Grip - Hooded capuchins have a semi-prehensile tail that they can use to grip objects. They have opposable thumbs and big toes on their hands and feet further enabling them to easily manipulate objects. They use their prehensile tail to anchor themselves when climbing around in the trees and to keep them from falling when they sleep. Unlike some monkeys with prehensile tails, capuchins cannot hang by their tail alone. Classification The hooded capuchin is also been referred to as the tufted or brown capuchin. Class: Mammalia Order: Primate Family: Cebidae Genus: Cebus Species: paella Subspecies: cay Distribution This species ranges through northern South America, specifically Venezuela, Brazil, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. Habitat Canopies of tropical and mountain rainforests. Physical Description • Hooded capuchins are 12-22 inches (30-56 cm) long with a 15-22 inch (38-56 cm) tail. • Adults weigh six to eight pounds (3-4 kg). • Their fur is light to dark brown with a distinctive black cap on the head. • They have semi-prehensile tails. • Hooded capuchins have tufts of hair that form ridges along the side of the top of their head. Diet What Does It Eat? In the wild: Fruit, flowers, leaves, insects, birds, eggs, lizards, and small mammals. -

F a C T S H E

F A C T S H E E T Recent Primate Incidents Demonstrate Risks To Public Health and Safety, Animal Welfare November 2009 (Indiana): A woman was holding her 10-month-old granddaughter near an enclosure where a monkey was kept as a pet. The monkey pulled the hood of the girl’s coat, causing her head to strike the metal cage, and pulled her hair. The child was taken to the hospital and released that night. November 2009 (Tennessee): A capuchin monkey was found on a road. He had escaped from an SUV of a family vacationing in the area while they were eating at a restaurant, and was recaptured. November 2009 (Florida): A macaque monkey was on the loose outside a Pinellas County apartment complex. October 2009 (Kentucky): Authorities found a baboon being kept in the garage of a Kenton County home. The owners said they bought the animal from an Ohio dealer, and they surrendered her to a sanctuary. September 2009 (Florida): Authorities were looking for a pet patas monkey who had escaped from a Marion County home and been on the loose about two months. June 2009 (New Hampshire): An employee of a farm was severely bitten by a macaque monkey after leaving an enclosure unsecured. Macaques often carry Herpes B virus, and research published by the CDC concludes the health risk makes macaques unsuitable as pets. April 2009 (Oregon): A man brought a capuchin monkey in a diaper to a park. A 6-year-old girl approached and the animal jumped on her, causing two puncture wounds below her eye. -

AFRICAN PRIMATES the Journal of the Africa Section of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group

Volume 9 2014 ISSN 1093-8966 AFRICAN PRIMATES The Journal of the Africa Section of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group Editor-in-Chief: Janette Wallis PSG Chairman: Russell A. Mittermeier PSG Deputy Chair: Anthony B. Rylands Red List Authorities: Sanjay Molur, Christoph Schwitzer, and Liz Williamson African Primates The Journal of the Africa Section of the IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group ISSN 1093-8966 African Primates Editorial Board IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group Janette Wallis – Editor-in-Chief Chairman: Russell A. Mittermeier Deputy Chair: Anthony B. Rylands University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK USA Simon Bearder Vice Chair, Section on Great Apes:Liz Williamson Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK Vice-Chair, Section on Small Apes: Benjamin M. Rawson R. Patrick Boundja Regional Vice-Chairs – Neotropics Wildlife Conservation Society, Congo; Univ of Mass, USA Mesoamerica: Liliana Cortés-Ortiz Thomas M. Butynski Andean Countries: Erwin Palacios and Eckhard W. Heymann Sustainability Centre Eastern Africa, Nanyuki, Kenya Brazil and the Guianas: M. Cecília M. Kierulff, Fabiano Rodrigues Phillip Cronje de Melo, and Maurício Talebi Jane Goodall Institute, Mpumalanga, South Africa Regional Vice Chairs – Africa Edem A. Eniang W. Scott McGraw, David N. M. Mbora, and Janette Wallis Biodiversity Preservation Center, Calabar, Nigeria Colin Groves Regional Vice Chairs – Madagascar Christoph Schwitzer and Jonah Ratsimbazafy Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Michael A. Huffman Regional Vice Chairs – Asia Kyoto University, Inuyama, -

Ancestral Facial Morphology of Old World Higher Primates (Anthropoidea/Catarrhini/Miocene/Cranium/Anatomy) BRENDA R

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 88, pp. 5267-5271, June 1991 Evolution Ancestral facial morphology of Old World higher primates (Anthropoidea/Catarrhini/Miocene/cranium/anatomy) BRENDA R. BENEFIT* AND MONTE L. MCCROSSINt *Department of Anthropology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901; and tDepartment of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Communicated by F. Clark Howell, March 11, 1991 ABSTRACT Fossil remains of the cercopithecoid Victoia- (1, 5, 6). Contrasting craniofacial configurations of cercopithe- pithecus recently recovered from middle Miocene deposits of cines and great apes are, in consequence, held to be indepen- Maboko Island (Kenya) provide evidence ofthe cranial anatomy dently derived with regard to the ancestral catarrhine condition of Old World monkeys prior to the evolutionary divergence of (1, 5, 6). This reconstruction has formed the basis of influential the extant subfamilies Colobinae and Cercopithecinae. Victoria- cladistic assessments ofthe phylogenetic relationships between pithecus shares a suite ofcraniofacial features with the Oligocene extant and extinct catarrhines (1, 2). catarrhine Aegyptopithecus and early Miocene hominoid Afro- Reconstructions of the ancestral catarrhine morphotype pithecus. AU three genera manifest supraorbital costae, anteri- are based on commonalities of subordinate morphotypes for orly convergent temporal lines, the absence of a postglabellar Cercopithecoidea and Hominoidea (1, 5, 6). Broadly distrib- fossa, a moderate to long snout, great facial -

Lemurs, Monkeys & Apes, Oh

Lemurs, Monkeys & Apes, Oh My! Audience Activity is designed for ages 12 and up Goal Students will be able to understand the differences between primate groups Objective • To use critical thinking skills to identify different primate groups • To learn what makes primates so unique. Conservation Message Many of the world’s primates live in habitats that are currently being threatened by human activities. Most of these species live in rainforests in Asia, South America and Africa, all these places share a similar threat; unstainable agriculture and climate change. In the last 20 years, chimpanzee and ring-tailed lemur populations have declined by 90%. There are some easy things we can do to help these animals! Buying sustainable wood and paper products, recycling any items you can, spreading the word about the issues and supporting local zoos and aquariums. Background Information There are over 300 species of primates. Primates are an extremely diverse group of animals and cover everything from marmosets to lorises to gorillas and chimpanzees. Many people believe that all primates are monkeys, however, this is incorrect. There are many differences between primate species. Primates are broken into prosimians (lemurs, tarsius, bushbabies and lorises), monkeys (Old and New World) and apes (gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos). Prosimians are primarily tree-dwellers. This group includes species such as lemurs, tarsius, bushbabies and lorises. They have longer snouts than other primates, a wet nose and a good sense of smell. They have smaller brains, large eyes that are adapted for night vision, and long tails that are not prehensile, meaning they are not able to grab onto items with their tails. -

Old World Monkeys in Mixed Species Exhibits

Old World Monkeys in Mixed Species Exhibits (GaiaPark Kerkrade, 2010) Elwin Kraaij & Patricia ter Maat Old World Monkeys in Mixed Species Exhibits Factors influencing the success of old world monkeys in mixed species exhibits Authors: Elwin Kraaij & Patricia ter Maat Supervisors Van Hall Larenstein: T. Griede & M. Dobbelaar Client: T. ter Meulen, Apenheul Thesis number: 594000 Van Hall Larenstein Leeuwarden, August 2011 Preface This report was written in the scope of our final thesis as part of the study Animal Management. The research has its origin in a request from Tjerk ter Meulen (vice chair of the Old World Monkey TAG and studbook keeper of Allen’s swamp monkeys and black mangabeys at Apenheul Primate Park, the Netherlands). As studbook keeper of the black mangabey and based on his experiences from his previous position at Gaiapark Kerkrade, the Netherlands, where black mangabeys are successfully combined with gorillas, he requested our help in researching what factors contribute to the success of old world monkeys in mixed species exhibits. We could not have done this research without the knowledge and experience of the contributors and we would therefore like to thank them for their help. First of all Tjerk ter Meulen, the initiator of the research for providing information on the subject and giving feedback on our work. Secondly Tine Griede and Marcella Dobbelaar, being our two supervisors from the study Animal Management, for giving feedback and guidance throughout the project. Finally we would like to thank all zoos that filled in our questionnaire and provided us with the information required to perform this research. -

1 Old World Monkeys

2003. 5. 23 Dr. Toshio MOURI Old World monkey Although Old World monkey, as a word, corresponds to New World monkey, its taxonomic rank is much lower than that of the New World Monkey. Therefore, it is speculated that the last common ancestor of Old World monkeys is newer compared to that of New World monkeys. While New World monkey is the vernacular name for infraorder Platyrrhini, Old World Monkey is the vernacular name for superfamily Cercopithecoidea (family Cercopithecidae is limited to living species). As a side note, the taxon including Old World Monkey at the same taxonomic level as New World Monkey is infraorder Catarrhini. Catarrhini includes Hominoidea (humans and apes), as well as Cercopithecoidea. Cercopithecoidea comprises the families Victoriapithecidae and Cercopithecidae. Victoriapithecidae is fossil primates from the early to middle Miocene (15-20 Ma; Ma = megannum = 1 million years ago), with known genera Prohylobates and Victoriapithecus. The characteristic that defines the Old World Monkey (as synapomorphy – a derived character shared by two or more groups – defines a monophyletic taxon), is the bilophodonty of the molars, but the development of biphilophodonty in Victoriapithecidae is still imperfect, and crista obliqua is observed in many maxillary molars (as well as primary molars). (Benefit, 1999; Fleagle, 1999) Recently, there is an opinion that Prohylobates should be combined with Victoriapithecus. Living Old World Monkeys are all classified in the family Cercopithecidae. Cercopithecidae comprises the subfamilies Cercopithecinae and Colobinae. Cercopithecinae has a buccal pouch, and Colobinae has a complex, or sacculated, stomach. It is thought that the buccal pouch is an adaptation for quickly putting rare food like fruit into the mouth, and the complex stomach is an adaptation for eating leaves. -

Monkey Business in the American Museum of Natural History Walton Ford’S Painting of a Historical Primate Banquet Belongs to a Rich in New York

OPINION NATURE|Vol 467|9 September 2010 ERY ERY ALL SMIN G SMIN A K L U A ESY P ESY T ORD, COUR ORD, F . W of birds by US painter John James Audubon (1785–1851). He also references the dioramas Monkey business in the American Museum of Natural History Walton Ford’s painting of a historical primate banquet belongs to a rich in New York. Ford gives a historic look to his works: in The Sensorium, he has artificially tradition of exploring the ‘human animal’, explains Martin Kemp. aged the paper and added inscriptions in a mock nineteenth-century hand. “He collected forty monkeys … and he US artist Walton Ford in The Sensorium (2003; Ford’s relationship to his historical heroes is used to call them by different offices. He pictured), a panoramic watercolour currently ambiguous. Audubon was a naturalist and artist had his doctor, his chaplain, his secretary, on show with other Ford paintings of alle- but, like many of his contemporaries, he killed his aide-de-camp, his agent, and one tiny gorical natural history at Vienna’s Albertina birds with happy abandon. Burton placed him- one, a very pretty, small, silky-looking museum in the exhibition Bestarium. self inside exotic cultures and criticized Brit- monkey, he used to call his wife, and put As a contemporary artist, Ford is a one-off. ish overseas rule, but he remained an integral pearls in her ears. His great amusement However, he belongs to a rich tradition in his part of a colonial enterprise. Ford comes from was to keep a kind of refectory for them, characterizations of the ‘human animal’. -

Status and Ecology of the Golden Monkey (Cercopithecus Mitis Kandti) in Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, Uganda

Status and ecology of the golden monkey (Cercopithecus mitis kandti) in Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, Uganda D. Twinomugisha1,G.I.Basuta1 andC.A.Chapman1,2,3 1Department of Zoology, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; 2Department of Zoology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA; and 3Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx, NY,USA Abstract illegal extraction of bamboo found during the census, conservation e¡orts should be increased. Given the degree to which tropical ecosystems are cur- rently being disturbed by human activities, it is essential Key words: conservation, diet, endangered, home range, to set priorities for conservation and thus it becomes hybridization important to consider how best to set these priorities. From this perspective, this study provides the ¢rst Re¨ sume¨ detailed investigations of Cercopithecus mitis kandti, the golden monkey, focusing on the population in Mgahinga Etant donne¨ la facËon dont les e¨ cosyste© mes tropicaux sont Gorilla National Park (MGNP), Uganda. Speci¢cally, we actuellement perturbe¨ s par les activite¨ s humaines, il est (1) establish the current status of the golden monkey in essentield'e¨ tablirdes priorite¨ senmatie© rede conservation terms of population size and distribution within the park et il est de plus en plus important de voir comment e¨ tablir in relation to vegetation types and altitude, and (2) inves- ces priorite¨ s. Dans cet esprit, cette e¨ tude rapporte les pre- tigate the golden monkey's feeding ecology. A total of 67 mie© res investigations de¨ taille¨ es mene¨ es sur Cercopithecus censuses of 4 km transects were conducted along a mitiskandti, le singe dore¨ , dans la population qui vit dans cumulative distance of 299 km and 132 social groups le Parc National des Gorilles de Mgahinga (MGNP), en were encountered. -

How Does the Golden Monkey of the Virungas Cope in a Fruit-Scarce Environment? Dennis Twinomugisha, Colin A

SVNY253-Newton-Fisher et al. March 31, 2006 23:19 CHAPTER THREE How Does the Golden Monkey of the Virungas Cope in a Fruit-Scarce Environment? Dennis Twinomugisha, Colin A. Chapman, Michael J. Lawes, Cedric O’Driscoll Worman, and Lisa M. Danish INTRODUCTION Understanding the processes determining the density and distribution of species is one of the primary goals of ecology (Boutin, 1990). The importance of this information has increased with the need to develop informed management plans for endangered or threatened species. With respect to primates, these theoretical issues are critical because the tropical forests they occupy are undergoing rapid r Dennis Twinomugisha Institute of Environmentr and Natural Resources, Makerere Univer- sity, Kampala, Uganda Colin A. Chapman Department of Zoology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611;r Wildlife Conservation Society, 2300 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, NY 10460 Michael J. Lawes Forest Biodiversity Programme, School of Botany and Zoology, University of Natal, P/Bagr X01, Scottsville, 3209, South Africa Cedric O’Driscoll Worman and Lisa M. Danish Department of Zoology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611. Primates of Western Uganda, edited by Nicholas E. Newton-Fisher, Hugh Notman, Vernon Reynolds, and James D. Paterson. Springer, New York, 2006. 45 SVNY253-Newton-Fisher et al. March 31, 2006 23:19 46 Primates of Western Uganda anthropogenic transformation and modification. For example, countries with primate populations are cumulatively losing approximately 125,000 km2 of forest annually (Chapman & Peres, 2001). Other populations are being affected by forest degradation (logging and fire) and hunting. However, predicting the responses of particular species has often proved difficult.