Understanding Developmental/Structural Disruptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work with Gay Men

Article 22 Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work With Gay Men Justin L. Maki Maki, Justin L., is a counselor education doctoral student at Auburn University. His research interests include counselor preparation and issues related to social justice and advocacy. Abstract Providing counseling services to gay men is considered an ethical practice in professional counseling. With the recent changes in the Defense of Marriage Act and legalization of gay marriage nationwide, it is safe to say that many Americans are more accepting of same-sex relationships than in the past. However, although societal attitudes are shifting towards affirmation of gay rights, division and discrimination, masculinity shaming, and within-group labeling between gay men has become more prevalent. To this point, gay men have been viewed as a homogeneous population, when the reality is that there are a variety of gay subcultures and significant differences between them. Knowledge of these subcultures benefits those in and out-of-group when they are recognized and understood. With an increase in gay men identifying with a subculture within the gay community, counselors need to be cognizant of these subcultures in their efforts to help gay men self-identify. An explanation of various gay male subcultures is provided for counselors, counseling supervisors, and counselor educators. Keywords: gay men, subculture, within-group discrimination, masculinity, labeling Providing professional counseling services and educating counselors-in-training to work with gay men is a fundamental responsibility of the counseling profession (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014). Although not all gay men utilizing counseling services are seeking services for problems relating to their sexual orientation identification (Liszcz & Yarhouse, 2005), it is important that counselors are educated on the ways in which gay men identify themselves and other gay men within their own community. -

The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials 7-28-1893 The Waterville Mail (Vol. 47, No. 09): July 28, 1893 Prince & Wyman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/waterville_mail Part of the Agriculture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Prince & Wyman, "The Waterville Mail (Vol. 47, No. 09): July 28, 1893" (1893). The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine). 1498. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/waterville_mail/1498 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Waterville Materials at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. VrOLUME XLVII. WATERVILLE, MAI FRIDAY, JULY 28, t893. NO. 9. wewaUc into the but (Captain came to my knowTedgo, and I wondet just lovo to have your A lohg walk ah>no in wldcli to rend my- TIIK.SK riCKRUKL AHR nKALTlIY. Sang. He told ns ‘ made their that yon can Indnlge yourself in inch “Well, ond here I imi." said sho. "So Pclf n leclun*. II-e j' bail I taki-n uinh-r rrntlilfil ilip Thf>y Hava May mn in the most * lie brief time, baimly whims. Here is a young lady that’s soon settUnl." iny ro<*f a young laxM e.Mremely iH-niui- Mrrvn nn a TriiNlwnrthy Symptom. II they reached the wind holding fltrong that was the best friend in the world to I knew 1 was in duty boiimloii to have ful. -

BANGKOK 101 Emporium at Vertigo Moon Bar © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely © MBK Sirocco Sky Bar Chao Phraya Express Chinatown Wat Phra Kaew Wat Pho (P171)

© Lonely Planet Publications 101 BANGKOK BANGKOK Bangkok In recent years, Bangkok has broken away from its old image as a messy third-world capital to be voted by numerous metro-watchers as a top-tier global city. The sprawl and tropical humidity are still the city’s signature ambassadors, but so are gleaming shopping centres and an infectious energy of commerce and restrained mayhem. The veneer is an ultramodern backdrop of skyscraper canyons containing an untamed universe of diversions and excesses. The city is justly famous for debauchery, boasting at least four major red-light districts, as well as a club scene that has been revived post-coup. Meanwhile the urban populous is as cosmopolitan as any Western capital – guided by fashion, music and text messaging. But beside the 21st-century façade is a traditional village as devout and sacred as any remote corner of the country. This is the seat of Thai Buddhism and the monarchy, with the attendant splendid temples. Even the modern shopping centres adhere to the old folk ways with attached spirit shrines that receive daily devotions. Bangkok will cater to every indulgence, from all-night binges to shopping sprees, but it can also transport you into the old-fashioned world of Siam. Rise with daybreak to watch the monks on their alms route, hop aboard a long-tail boat into the canals that once fused the city, or forage for your meals from the numerous and lauded food stalls. HIGHLIGHTS Joining the adoring crowds at Thailand’s most famous temple, Wat Phra Kaew (p108) Escaping the tour -

Terminology Packet

This symbol recognizes that the term is a caution term. This term may be a derogatory term or should be used with caution. Terminology Packet This is a packet full of LGBTQIA+ terminology. This packet was composed from multiple sources and can be found at the end of the packet. *Please note: This is not an exhaustive list of terms. This is a living terminology packet, as it will continue to grow as language expands. This symbol recognizes that the term is a caution term. This term may be a derogatory term or should be used with caution. A/Ace: The abbreviation for asexual. Aesthetic Attraction: Attraction to someone’s appearance without it being romantic or sexual. AFAB/AMAB: Abbreviation for “Assigned Female at Birth/Assigned Male at Birth” Affectionional Orientation: Refers to variations in object of emotional and sexual attraction. The term is preferred by some over "sexual orientation" because it indicates that the feelings and commitments involved are not solely (or even primarily, for some people) sexual. The term stresses the affective emotional component of attractions and relationships, including heterosexual as well as LGBT orientation. Can also be referred to as romantic orientation. AG/Aggressive: See “Stud” Agender: Some agender people would define their identity as not being a man or a woman and other agender people may define their identity as having no gender. Ally: A person who supports and honors sexual diversity, acts accordingly to challenge homophobic, transphobic, heteronormative, and heterosexist remarks and behaviors, and is willing to explore and understand these forms of bias within themself. -

Chubby Men for Sex Dating

Chubby Gay Dating for Free! More and more gay, bisexual and bi-curious men are choosing to hookup online in the gay personals, and now you can start your search absolutely free!There are now far more benefits to meeting gay men online than there used to be. For casual hookups but also for serious dating, we have it all. We have thousands of active members here and all the men are looking to hook up with plus size women. Find your new plus size love, a nasty bbw for hardcore sex or a new friend, whatever you're looking for you'll find it. So sign up right now and dive into the world of BBW sex dating. renuzap.podarokideal.ru is for Gay Men looking to find other Chubby Gay Men for both casual and serious dating and romance. This site features only real Chubby Gay men who are interested in being something more than friends. Gay dating sites usually charge you too much and offer too little. Our Gay Chubby personals site will give you just what you. Further, all members of this dating site MUST be 18 years or older. Gay Chub Personals is part of the Infinite Connections dating network, which includes many other general and bhm dating sites. As a member of Gay Chub Personals, your profile will automatically be shown on related bhm dating sites or to related users in the Infinite Connections. If you love chubby singles, then you need to get online with Gay Chub Dating tonight! It is hard to find love when you are chubby and the world judges you by your appearances. -

Business Achievers Awards – Winners Are a Hit

FEB - APR 2020 YOUNG BUSINESS ACHIEVERS AWARDS – WINNERS ARE A HIT KENAKO - THEIR TIME HAS COME WORKING FROM HOME KHAZAN’S RICH HISTORICAL CHARM VIDEO MARKETING ETIQUETTE WRITING AND POETRY IN MOTION Vereeniging Trust T The Property People Innovation that excites Don’t Forget !! FOR ✓ Letting – Commercial, Industrial & Residential ✓ Sales – Commercial & Industrial ✓ Property Administration ✓ Property Development and Turnkey Developments THE PROPERTY PEOPLE WITH OVER 65 YEARS EXPERIENCE 011 835 3535 | 20 Crownwood Road, Ormonde, Johannesburg www.motordeal.co.za | email: [email protected] 31 Leslie Street, P O Box 89, Vereeniging, 1939 Tel: 016-421-1304 e-mail: [email protected] www.vertrust.co.za www.neonprint.co.za 5L Turps R98 5L Supa Satin white PVA R370 20L Supa Satin White PVA R1 260 5L All Purpose Matt White R250 C 20L All Purpose Matt White R810 M 5L QD Red Oxide Primer R168 Y 5L Eggshell Enamel White R350 CM 20L Eggshell Enamel White R1 170 MY 5L Gloss Enamel White R340 CY 20L Gloss Enamel White R1 150 CMY 5L Contractor's White R75 Technology has perfected the art of printing. K At Neon Printers we believe that quality service delivers quality products. 20L Contractor's White R240 Our innovative quest for the optimum solution has placed us in the 20L Dulux Weatherguard forefront of leading-edge technologies. (white and standard colours) Special 20L Roof Paint from R560 [email protected] MEDIADYNAMIX Ed’s Entre ust when one had thought there is no hope, the Young Contents JBusiness Achievers Awards and our participants spreads hope and charm. -

June 18, 2020 Webinar: Fat & Queer Intersections -START

June 18, 2020 Webinar: Fat & Queer Intersections -START- Tigress Osborn (TO): Hi everyone, welcome to the newest installment of our 2020 NAAFA webinar series. I am Tigress Osborn, I am NAAFA’s Director of Community Outreach. Today we are gonna be talking about Queer and Fat identity and the intersections of those identities. I’m joined by three very special guests, but before I let them introduce themselves today, I want to just give you a little bit of information about NAAFA for those of you who may be joining us the first time and a couple of announcements and then we’ll get right on to our hosts. If you are new to NAAFA, NAAFA is the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance. We are a fifty, now fifty- one year old, civil rights organization working to protect the rights of fat people. And working to improve the lives of fat people. As you can tell from our name and if you have ever encountered us out in the wild we fully believe in embracing the word “fat”. We will be using the word “fat” during this webinar, we’ll hear from our speakers about what they think about that word and other words for fat folks. But that’s what we say around these parts. Thank you for being here with us. Today’s webinar will be in English and it, there are not captions available through Free Conference. We will have a transcript of the webinar available for you at a later date. I want to tell you that we are very excited, in addition to the three fabulous folks we have today, that we have two upcoming webinars scheduled for June 26th Gloria Lucas from Nalgona Positivity Pride will be joining us to talk about colonialism and its effects on body image. -

Media's Influence on LGBTQ Support Across Africa

Media's Influence on LGBTQ Support across Africa∗ Stephen Winklery July 14, 2019 This manuscript is forthcoming in the British Journal of Political Science. Abstract Political leaders across Africa frequently accuse the media of promoting homosexuality while activists often use the media to promote pro-LGBTQ narratives. Despite ex- tensive research on how media affects public opinion, including studies that show how exposure to certain information can increase support of LGBTQs, there is virtually no research on how media influences attitudes towards LGBTQs across Africa. I develop a theory that accounts for actors' mixed-approach to the media and show how differ- ent types of media create distinct effects on public opinion of LGBTQs. Specifically, I find that radio and television have no, or a negative, significant effect on pro-gay attitudes, whereas individuals who consume more newspapers, internet or social media are significantly more likely to support LGBTQs (by approximately 2 to 4 per cent). I argue that these differential effects are conditional on censorship of queer represen- tation from certain mediums. My analysis confirms that the results are not driven by selection effects, and that the relationship is unique to LGBTQ support but not other social attitudes. The results have important implications, especially given the growing politicization of same-sex relations and changing media consumption habits across Africa. ∗I thank Jeffrey Arnold, Chris Adolph, Sarah Dreier, Mary Kay Gugerty, Meredith Loken, James Long, Beatrice Magistro, Nyambura Mutanyi, Vanessa Quince, and Nora Webb Williams for helpful feedback on various drafts of this article. I also thank the editors and anonymous reviewers at the British Journal of Political Science for incisive and invaluable comments. -

LBGTQI Gay Vocabulary

LGBTQI Vocabulary David Sweetnam GetIntoEnglish.com Welcome! Hi! Thank you for downloading this guide to LGBTQI vocabulary. Before we get started, let me introduce myself. I'm David, the creator of Get Into English, a website for learners of English. One of my goals is to present to you lots of natural English vocabulary used in both small talk and deeper extended conversation. I also would like to cover some topics and ideas which are not included in mainstream English coursebooks and blogs. This first guide is connected to the discussion surrounding gay and lesbian issues. Regardless of where you stand, it's a widelydiscussed topic in Australia, and if you'd like to contribute to the conversation, here is an extensive list of words, phrases and other collocations you can use. One last thing this guide is suitable for adults or mature audiences. Please do not read if you're not comfortable with adult themes. Please feel to leave a comment on the original blog article once you've finished and I hope you find this helpful! Best wishes David Sweetnam April 2016 Melbourne Australia Disclaimer: This is a list of vocabulary for learning English. It should not be taken as any kind of medical, legal or any other kind of professional advice. © David Sweetnam GetIntoEnglish.com Types Of People People who are heterosexual are attracted to the opposite sex. They are sometimes called straight or hetro (ie when a man and a woman are together). The term LGBTQI refers to people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or questioning) and intersex. -

Gay Men's Experience of and Resistance Against Weight and Sexual Orientation Stigma Patrick Blaine Mcgrady

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Sexuality and Larger Bodies: Gay Men's Experience of and Resistance Against Weight and Sexual Orientation Stigma Patrick Blaine McGrady Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND PUBLIC POLICY SEXUALITY AND LARGER BODIES: GAY MEN’S EXPERIENCE OF AND RESISTANCE AGAINST WEIGHT AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION STIGMA By PATRICK BLAINE MCGRADY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall 2012 Patrick B. McGrady defended this dissertation on August 31, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: John Reynolds Professor Directing Dissertation Jasminka Illich-Ernst University Representative Douglas Schrock Committee Member Koji Ueno Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number of people who deserve acknowledgement for making this dissertation possible. I would first like to thank my advisor and mentor, John Reynolds, who is the chair of my dissertation committee. From day one at orientation where he “welcomed me aboard,” John helped me organize my life as a graduate student, set high goals for me, and even stuck with me through a radical dissertation topic change. While writing this, his enthusiasm during our brainstorm meetings where we both scrambled to take notes that probably would not make sense to anyone else energized me and helped take a study about a subculture to something more general and methodologically savvy. -

View Entire Issue As

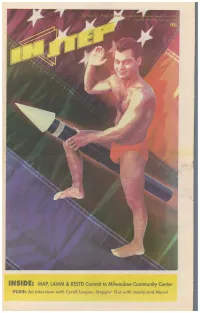

MINENNIMMIMMIN. Miler t•J:: e(Ild Filiri ii/111/C1/i r June 26, 1997 • Vd. k, I FREE INSIDE: MAP, LAMM & BESTD Commit to Milwaukee Community Center PLUS: An interview with Cyndi Lauper, Steppin' Out with Jamie and More! VOL. XIV, ISSUE XIII • JUNE 26, 1997 NEWS Community Center Gains Support 5 Religious Right Boycotts Disney 6 In Step Newsmagazine AIDS Debate Highlights Differences 7 1661 N. Water Street, Suite 411 Milwaukee, WI 53202 DEPARTMENTS (414) 278-7840 voice • (414) 278-5868 fax Group Notes 10 INSTEPWI@AOLCOM Opinion 14 Letters 15 ISSN# 1045-2435 The Arts 20 Ronald F. Geiman The Calendar 26 founder The Classies 31 The Guide 33 Jorge L. Cabal president William Attewell FEATURES editor-in-chief Cyndi Lauper Interview by Tim Nasson 15 New York, New York Travel Feature by Paul Hoffman 25 Jorge L.Cabal arts editor COLUMNS AND OPINION Manuel Kortright Tribal Talk by Ron Geiman 14 calendar editor Queer Science by Simon LeVey 27 John Quinlan Out of the Stars Horoscope by Charlene Lichtenstien 29 Madison Bureau Outings 30 Keepin' In Step by Jamie Taylor 30 Keith Clark, Ron Geiman, Ed Grover, Kevin Isom, Jamakaya, Owen Keehnen, Christopher Krimmer, Jim W. Lautenbach, Charlene Lichtenstein, Marvin Liebman, Cheryl Myers, Richard Mohr, Dale Reynolds, Shelly Roberts, Jamie Taylor, Rex Wockner, Arlene Zarembka, Yvonne Zipter contributing writers IN STEP MAGAZINE OFFICE HOURS: James Taylor Our offices are open to the public from photographer 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday at: Robert Arnold, Paul Berge cartoonists The Northern Lights Building 1661 North Water Street, Suite 411 Wells Ink art direction and ad design Milwaukee, WI 53202 Publication of the name, photograph or other likeness of any person or organization in In Step Newsmagazine is not to be construed as any indication of the sexual, religious or political orientation, practice or beliefs of such person or members of such organiza- tions. -

Trainer Guide a Provider's Introduction To

Unifying science, education and service to transform lives TTrraaiinneerr GGuuiiddee AA PPrroovviiddeerr’’ss IInnttrroodduuccttiioonn ttoo SSuubbssttaannccee AAbbuussee TTrreeaattmmeenntt ffoorr LLeessbbiiaann,, GGaayy,, BBiisseexxuuaall,, aanndd TTrraannssggeennddeerr IInnddiivviidduuaallss Fiirst Ediitiion Based on the publliicatiion: (DHHS Publliicatiion No. (SMA) 01-3498) Training Curriculum Acknowledgements A Provider’s Introduction to Substance Abuse Treatment for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Individuals This training curriculum was edited and prepared for publication by the Prairielands Addiction Technology Transfer Center. Anne Helene Skinstad, PhD, Project Director, Prairielands ATTC, Associate Professor, Community and Behavioral Health, College of Public Health, The University of Iowa Jennifer Kardos, MA, Instructional Designer, Prairielands ATTC Candace Peters, MA, CADC, Director of Training, Prairielands ATTC The original curriculum and training activities were authored by : Barbara Warren, PsyD, CASAC, CPP, Director of Organizational Development, Planning and Research, The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center of New York City Elijah C. Nealy, LCSW, Deputy Director for Programs, The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center of New York City. Technical guidance and program direction were provided by: Edwin M. Craft, DrPH, MED, LCPC, Lead Government Project Officer/Activities Coordinator for Methamphetamine, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance