A Brief and True Account of the History of South Carolina Plantation Archaeology and the Archaeologists Who Practice It by Linda F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Take a Lesson from Butch. (The Pros Do.)

When we were children, we would climb in our green and golden castle until the sky said stop. Our.dreams filled the summer air to overflowing, and the future was a far-off land a million promises away. Today, the dreams of our own children must be cherished as never before. ) For if we believe in them, they will come to believe in I themselves. And out of their dreams, they will finish the castle we once began - this time for keeps. Then the dreamer will become the doer. And the child, the father of the man. NIETROMONT NIATERIALS Greenville Division Box 2486 Greenville, S.C. 29602 803/269-4664 Spartanburg Division Box 1292 Spartanburg, S.C. 29301 803/ 585-4241 Charlotte Division Box 16262 Charlotte, N.C. 28216 704/ 597-8255 II II II South Caroli na is on the move. And C&S Bank is on the move too-setting the pace for South Carolina's growth, expansion, development and progress by providing the best banking services to industry, business and to the people. We 're here to fulfill the needs of ou r customers and to serve the community. We're making it happen in South Carolina. the action banlt The Citizens and Southern National Bank of South Carolina Member F.D.I.C. In the winter of 1775, Major General William Moultrie built a fort of palmetto logs on an island in Charleston Harbor. Despite heavy opposition from his fellow officers. Moultrie garrisoned the postand prepared for a possible attack. And, in June of 1776, the first major British deftl(lt of the American Revolution occurred at the fort on Sullivan's Island. -

South Carolina SOUTH CAROLINA

South Carolina `I.H.T. Ports and Harbors: 7 SOUTH CAROLINA, USA Airports: 6 SLOGAN: PALMETTO STATE ABBREVIATION: SC HOTELS / MOTELS / INNS AIKEN SOUTH CAROLINA COMFORT SUITES 3608 Richland Ave. W. - 29801 AIKEN SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (803) 641-1100, www.comfortsuites.com AIKEN SOUTH CAROLINA EXECUTIVE INN 3560 Richland Ave W Aiken UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 803-649-3968 803-649-3968 ANDERSON SOUTH CAROLINA COMFORT SUITES 118 Interstate Blvd. - 29621 ANDERSON SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (864) 375-0037, www.comfortsuites.com KNIGHTS'INN 2688 Gateway Drive Anderson UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 530-365-2753 530-365-6083 QUALITY INN 3509 Clemson Blvd. - 29621 ANDERSON SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (864) 226-1000 BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA COMFORT INN 2625 W. Boundary St. (US 21) - 29902 BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (843) 525-9366, www.comfortinn.com BEAUFORT SOUTH SLEEP INN 2625 Boundary Street PO Box 2146-29902 BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA State Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++1 803 CHARLESTON SOUTH CAROLINA South Carolina Tourism Sales Office: 1205 Pendleton Street, Suite 112, ANCHORAGE INN, 26 Vendue Range Street, Charleston, SC 29401, United Columbia, SC 29201 Tel: 734 0128 Fax: 734 1163 E-mail: [email protected] States, (843) 723-8300, www.anchoragencharleston.com Website: www.discoversouthcarolina.com ANDREW PINCKNEY INN, 40 Pinckney Street, Charleston, SC 29401, United Capital: Columbia Time: GMT – 5 States, (843) 937-8800, www.andrewpinckneyinn.com Background: South Carolina entered the Union on May 23, 1788, as the eighth of BEST WESTERN KING CHARLES INN, 237 Meeting Street, Charleston, SC the original 13 states. -

Archeology at the Charles Towne Site

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Research Manuscript Series Institute of 5-1971 Archeology at the Charles Towne Site (38CH1) on Albemarle Point in South Carolina, Part I, The exT t Stanley South University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation South, Stanley, "Archeology at the Charles Towne Site (38CH1) on Albemarle Point in South Carolina, Part I, The exT t" (1971). Research Manuscript Series. 204. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archanth_books/204 This Book is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Manuscript Series by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archeology at the Charles Towne Site (38CH1) on Albemarle Point in South Carolina, Part I, The exT t Keywords Excavations, South Carolina Tricentennial Commission, Colonial settlements, Ashley River, Albemarle Point, Charles Towne, Charleston, South Carolina, Archeology Disciplines Anthropology Publisher The outhS Carolina Institute of Archeology and Anthropology--University of South Carolina Comments In USC online Library catalog at: http://www.sc.edu/library/ This volume constitutes Part I, the text of the report on the archeology done at the Charles Towne Site in Charleston County, South Carolina. A companion -

Moncks Corner Comprehensive Plan 2017

MONCKS CORNER COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2017 Planning Commission Adopted May 16, 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The 2017 Moncks Corner Comprehensive Plan was developed by a collaboration of the following: MONCKS CORNER PLANNING COMMISSION MONCKS CORNER TOWN COUNCIL Rev. Robin McGhee-Frazier (Co-Chair) Mayor Michael A. Lockliear Tobie Mixon (Co-Chair) David A. Dennis, Mayor Pro-Tem Mattie Gethers Johna T. Bilton Chris Griffin Charlotte A. Cruppeninck (PC Ex-officio member) Roscoe Haynes James N. Law Jr. Ryan Nelson Chadwick D. Sweatman Connor Salisbury Dr. Tonia A. Taylor Karyn Grooms (Alternate) TOWN STAFF Jeff Lord - Town Administrator Doug Polen - Community Development Director Marilyn Baker - Clerk Treasurer With assistance of the Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Council of Governments CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................................1 Background ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................................3 Community Vision ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

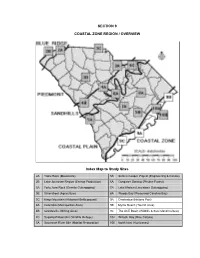

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

American Revolution & Constitution 1770-1785

TRAVELING THROUGH SOUTH CAROLINA HISTORY THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION AND CONSTITUTION (C. 17701770----1785)1785) South Carolina played a significant role in the American Revolution and the development of the United States as a nation. Our state has several battlefields related to the Revolution and historic sites associated with early American leaders. Andrew Jackson State Park Heyward Washington House Lancaster Charleston 803-285-3344 843-722-2996 http://www.southcarolinaparks.com/andrewjackson/ http://www.charlestonmuseum.org/heyward-washington-house Charles Pinckney National Historic Site Kings Mountain National Military Park Mount Pleasant Highway 216 near Blacksburg 843-881-5516 864-936-7921 http://www.nps.gov/chpi/index.htm http://www.nps.gov/kimo/index.htm Cowpens National Battlefield Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon Gaffney Charleston 864-461-7795 843-727-2165 http://www.nps.gov/cowp/index.htm http://oldexchange.org/ Drayton Hall Musgrove Mill State Historic Site Charleston Clinton 843-769-2600 864-938-0100 http://draytonhall.org/ http://www.southcarolinaparks.com/musgrovemill Fort Moultrie National Monument Ninety Six National Historic Site Sullivan’s Island Ninety Six 843-883-3123 864-543-4068 http://www.nps.gov/fosu http://www.nps.gov/nisi/index.htm Hampton Plantation State Historic Site SC Confederate Relic Room & Military Museum McClellanville Columbia 843-546-9361 803-737-8095 http://southcarolinaparks.com/hampton/ http://www.crr.sc.gov/ Historic Brattonsville Walnut Grove Plantation McConnells Roebuck 803-684-2327 864-576-6546 http://chmuseums.org/brattonsville/ http://www.spartanburghistory.org/walnutgrove.php Historic Camden Revolutionary War Site, Camden 803-432-9841 http://www.historic-camden.net/ This is one of eight brochures produced by the State Historic Preservation Office to promote South Carolina's historic places based on the 2011 Social Studies Standards. -

Appendix E Community Characterization Report

LC Appendix E Community Characterization Report RT This page intentionally left blank. Community Characterization Report Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Description ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Community Characterization .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Environmental Justice .................................................................................................... 7 1.4 Limited English Proficiency ............................................................................................. 8 2 Regional Context ................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 History ............................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Local Plans and Initiatives ............................................................................................ 12 2.3 Transportation .............................................................................................................. 20 2.4 Economic Outlook and Employment ............................................................................ 22 2.5 Socioeconomic Characteristics .................................................................................... 24 -

Site 1 Overview

SECTION 1 SOUTH CAROLINA'S INTRIGUING LANDSCAPE (STATEWIDE OVERVIEW) Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Producti 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay ( Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battlegrou 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restorat 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 1 SOUTH CAROLINA'S INTRIGUING LANDSCAPE (STATEWIDE OVERVIEW) - Index Map to Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 1 - Power Thinking Activity - "The Hydrophobic Horse" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 1-2 . - South Carolina's Five Landform Regions p. 1-2 . - figure 1-1 - "Landform Regions of South Carolina" p. 1-3 . - Differences Between Piedmont and Coastal Rivers p. 1-4 . - Drainage Patterns and Watersheds p. 1-5 . - figure 1-2 - "State Map of Major Drainage Basins" p. 1-6 . - figure 1-3 - "Average Annual Precipitation" p. 1-6 . - figure 1-4 - "Average Annual Temperature" p. 1-7 . - Geological Events that Shaped South Carolina's Landscape p. 1-8 . - figure 1-5 - "Geologic Cross-Section of South Carolina" p. 1-9 . - figure 1-6 - "The Geologic Time Scale and South Carolina" p. 1-11 . - figure 1-7 - "Geologic Map of South Carolina" - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. -

2020 Charleston Area Road Races, Trail Runs

Last Updated: 10/27/20 2020 CHARLESTON AREA ROAD RACES, TRAIL RUNS, ENDURANCE, MULTI-SPORT 2020 Start 2020 End Sports Type Sports Event Event Organizer(s) Venue(s) Municipality / Area Web site 1/1/20 1/1/20 Road Race Race the Landing New Year Pajama Run 5K/10K TimingInc.com Charles Towne Landing Charleston New Year Day Pajama Run 1/4/20 1/4/20 Road Race Bulldog Breakaway New Year's 5K The Citadel The Citadel Charleston Bulldog Breakaway New Years 5K 1/11/20 1/11/20 Marathon Charleston Marathon, 1/2 and 5K (10th) Capstone Event Group Charleston Charleston Charleston Marathon 1/18/20 1/18/20 Duathlon Off-Road Duathlon Run (2m+2m) and Bike (7m) (3rd) CCPRC Laurel Hill County Park Mt. Pleasant Off-Road Duathlon 1/18/20 1/18/20 Road Race Frozen: H3 100K, 60K, and 16.3 miles Trail Run Jerico Horse Trails- Bethera - Berkeley CountyFrozen: H3 1/25/20 1/25/20 Road Race Charlie Post Classic 15K/5K (37th) CRC Sullivan's Island Sullivan's Island Charlie Post Classic 15K/5K 1/25/20 1/25/20 Fun Run The Great Amazing Race 1.5m West Ashley Park Charleston The Great Amazing Race 2/1/20 2/1/20 Road Race Hallucination 24 Hr Trail Run (6HR/12H/24HR) Middleton Place Charleston Hallucination 6/12/24 Hour Trail Run 2/1/20 2/1/20 1/2 Marathon Save the Light 1/2M and 5K CCPRC Folly Beach Pier Folly Beach Save The Lighthouse 13.1 & 5K 2/8/20 2/8/20 Road Race Cupids Chase 5K Summerville Summerville Cupid's Chase 5K 2/8/20 2/8/20 Road Race Mardi Gras 5K and Fun Run Blessed Sacred Catholic Church James Island County Park James Island Mardi Gras 5K and Fun Run 2/12/20 -

2010 303(D) List Due to Standard Attainment, Identified Pollutant Or Listing Error

The State of South Carolina’s 2010 Integrated Report Part I: Listing of Impaired Waters INTRODUCTION The South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (Department) developed this priority list of waterbodies pursuant to Section §303(d) of the Federal Clean Water Act (CWA) and Federal Regulation 40 CFR 130.7 last revised in 1992. The listing identifies South Carolina waterbodies that do not currently meet State water quality standards after application of required controls for point and nonpoint source pollutants. Use attainment determinations were made using water quality data collected from 2004-2008. Pollution severity and the classified uses of waterbodies were considered in establishing priorities and targets. The list will be used to target waterbodies for further investigation, additional monitoring, and water quality improvement measures, including Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs). Over the past three decades, impacts from point sources to waterbodies have been substantially reduced through point source controls achieved via National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. Since 1990, steady progress in controlling nonpoint source impacts has also been made through implementation of South Carolina’s Nonpoint Source Management Program. In conjunction with TMDL development and implementation, the continued expansion and promotion of these and other state and local water quality improvement programs are expected to be effective in reducing the number of impaired waterbodies. In compliance with 40 CFR 25.4(c), the Department, beginning February 8, 2010, issued a public notice in statewide newspapers, to ensure broad notice of the Department's intent to update its list of impaired waterbodies. Public input was solicited. -

State Parks Garden Booklet

Rose Hill Plantation State Historic Site Heirloom Kitchen Garden Historic Gardens The Heirloom Kitchen Garden at Rose Hill Planta- tion represents the original gardens which would have supplied the table of South Carolina’s Governor of in SC State Parks Secession William H. Gist. The Rose Hill Heirloom Kitchen Garden includes Kitchen Gardens, Fruit Orchards and Vineyards heirloom varieties like Chioggia Beets, Purple Wonder Eggplant, Speckled Glory Butterbeans, Annie Wills Watermelon, Redleaf Cotton, Indigo, Old Henry Sweet Potato, as well as varieties of sweet onions, red cab- bage, potatoes, tomatoes, peanuts, pumpkins, okra, corn and pole beans. Herbs in- clude savory, chives, sweet basil, feverfew, horehound, tansy, dill, catmint and sweet parsley. The site also contains several ornamental rose gardens. Garden related programs include Heirloom Gardening: Spring Vegetables and Roses and The Fall Garden: Heirloom Vegetables and Roses . The garden is open during normal park operating hours for self-guided tours. Andrew Jackson State Park Charles Towne Landing 196 Andrew Jackson Park Rd. State Historic Site Lancaster, SC 29720 1500 Old Towne Rd. (803) 285-3344 Charleston, SC 29407 Open Hours: 8am - 6pm (winter), (843) 852-4200 9am - 9pm (summer) Open Hours: Daily 9am - 5pm Office Hours: 11am—Noon Office Hours: Daily 9am - 5pm Kings Mountain State Park Redcliffe Plantation 1277 Park Rd. State Historic Site Blacksburg, SC 29702 181 Redcliffe Rd (803) 222-3209 Beech Island, SC 29842 Open Hours: 8am - 6pm (winter), (803) 827-1473 7am - 9pm (summer) Open Hours: Thurs-Mon 9am-6pm Office Hours: 11am - Noon, 4 pm - (5pm in winter) 5pm Mon-Fri Office Hours: 11am—Noon Rose Hill Plantation State Historic Site 2677 Sardis Rd.