The Development of Tokyo's Rail Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAITAMA, JAPAN Just North of Tokyo Nature, Koedo, Shopping and Events

Crayon Shin-chan There's plenty to see! © U/ F・S・A・A , Saitama Sightseeing Supporter SAITAMA, JAPAN Just North of Tokyo Nature, Koedo, shopping and events Chichibu & North Area West Area Central & East Area Crayon Shin-chan © U/ F・S・A・A , Saitama Sightseeing Supporter Tourism Division, Department of Industry and Labor, Saitama Prefecture ※Some of the facilities shown in this brochure may be temporarily closed, or their hours may be changed due to COVID-19. Please also note that events and festivals may either be delayed or canceled. Thank you for understanding. Visit Saitama Prefecture, where you can experience the past and present of Japan! The Chichibu Area and North Area are full of the appeal of richGUMMA nature, the West Area is where you can feel the atmosphere of Japan, and the Central Area and East Area are a fusion of city and nature. Experience Japanese history and culture in Saitama Prefecture, which is full of attractions! Fujioka IC Fujioka JCT y a w Tobu Nikko Line s e s pr x Joetsu Shinkansen/Hokuriku Shinkansen E 17 u k o Chichibu & North Area h o Chichibu Area and the North Area are full of excitement. T Refresh the soul in magnifi cent natural beauty of Chichibu and T o Hanyu IC b Nagatoro, and taste local dishes of the North Area that have Gyodashi u Ise Sta. s → FOR ak been developed independently. Tohoku Shinkansen 140 125 i L Kazo IC Narita Kumagaya Sta.Takasaki Line ine Airport Hanazono IC H a c Nagatoro Sta. h Kan-etsu ik o L Expressway y ine Kuki a w Shiraoka- l IC Mandarin orange i a Ogawamachi Sta. -

1. 1.1 February 1.2 Conducte 2. 2.1 Between Their Ide 3. 3.1 Will Act 3.2

ISTF/1-IP/1 27/02/12 International Civil Aviation Organization FIRST MEETING OF IONOSPHERIC STUDIES TAKS FORCE (ISTF/1) 27-29 February 2012, Tokayo, Japan MEETING BULLETIN 1. Schedule of meeting 1.1 The opening session of the meeting will be held at 0930 hours on Monday, 27 February 2012 at the Mita Kaigisho, (Mita Conference Hall), Tokyo, Japan. 1.2 The technical tour to Electronic Navigation Research Institute (ENRI) will be conducted from 1000 to 1200 hours on Wednesday, 29 February 2012. 2. Registration of participants 2.1 Participants are requested to register at the Registration Desk of the Mita Kaigisho between 0915 - 0930 hours on the opening day of the meeting. Participants are also requested to wear their identification badge all the time inside the Mita Kaigisho. 3. Officers and Secretariat concerned with the meeting 3.1 Mr. Sujan K. Saraswati, Regional Officer CNS of the ICAO Asia and Pacific Office will act as Secretary of the meeting. His contact address is as follows: Mr. Sujan K. Saraswati, Regional Officer CNS Tel: +66 (2) 537 8189 to 97 Ext. 155 Fax: +66 (2) 537 8199 E-mail: [email protected] 3.2 The daily meeting service is the responsibility of Dr. Susumu Saito. Dr. Saito will provide secretarial support. The contact address is as follows: Dr. Susumu Saito, Senior Researcher, CNS Department Electronic Navigation Research Institute (ENRI) Tel: +81 422 413 191 Fax: +81 422 413 199 E-mail: [email protected] 4. Meeting documents for distribution 4.1 Participants wishing to make presentations or present papers for distribution during the meeting are requested to submit electronic copies to the Secretariat as early as possible, and preferably no later than 13 Febrruary 2012 at the following email addresses: [email protected] and cc: [email protected] ISTF/1-IP/1 -2- 27/02/12 5. -

Presentation File(PDF 4.3

JR East Group Management Vision “Move Up” 2027 Investor Meeting July 4, 2018 Table of Contents 1. Changes in the business environment P3 2. JR East Group’s strengths P5 3. Basic Policies of “Move Up” 2027 P6 4. “Move Up” 2027 (1) Overview P8 (2) Making cities more comfortable P12 (3) Making regional areas more affluent P21 (4) Developing businesses for the world P23 (5) Numerical targets (FY2023), etc. P24 Environmental Group “Move Up” 2027 “Move Up” 2027 1. Changes in the business environment: Decreasing population change strengths Basic Policies Overview Urban cities Regional areas World Targets ■ After 2025, the population in Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba, Kanagawa) is expected to decrease gradually. ■ In Tohoku region (Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Akita, Yamagata, Fukushima), the population is expected to decrease by nearly 30% by 2040. (Population in 2015 = 100) 100% Tokyo metropolitan area 90% JR East service area National 80% By 2040 Tohoku region 70% 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 (Year) Decrease by nearly 30% Source: IPSS (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research) Population Projections by Prefecture (2018) 3 Environmental Group “Move Up” 2027 “Move Up” 2027 1. Changes in the business environment: Decreasing need for railway transportation change strengths Basic Policies Overview Urban cities Regional areas World Targets ■ After 2020, due to decreasing population, changes in the working style, development of internet society and practical application of autonomous driving technologies, the need for railway transportation is expected to decline. Since our railway business has large xed costs, we face a high risk of a drastic prot loss. -

The Chiba Bank, Ltd. Integrated Report 2020

The Chiba Bank, Ltd. Integrated Report 2020 The Chiba Bank, Ltd. 1-2, Chiba-minato, Chuo-ku, Chiba-shi, Chiba 260-8720, Japan Integrated Report Phone: 81-43-245-1111 https://www.chibabank.co.jp/ 005_9326487912009.indd 1-3 2020/09/10 11:20:10 Introduction Our Philosophy Corporate Data The Chiba Bank, Ltd. As of March 31, 2020 Aiming to enhance “customer Principal Shareholders experience” as a partner to customers The ten largest shareholders of the Bank and their respective shareholdings as of March 31, 2020 were as follows: Number of Shares Percentage of Total (in thousands)*1 Shares Issued*2 (%) and regional communities The Master Trust Bank of Japan, Ltd. (Trust Account) 56,139 7.55 Japan Trustee Services Bank, Ltd. (Trust Account) 35,615 4.79 Nippon Life Insurance Company 26,870 3.61 The Dai-ichi Life Insurance Company, Limited 26,230 3.53 Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Insurance Inc.*3 18,537 2.49 Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company 18,291 2.46 SUMITOMO LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY 17,842 2.40 MUFG Bank, Ltd. 17,707 2.38 STATE STREET BANK AND TRUST COMPANY 505223 14,576 1.96 Japan Trustee Services Bank, Ltd. (Trust Account 5) 13,406 1.80 Management Policy Excluded from the figures above are 72,709 thousand treasury shares in the name of the Chiba Bank, Ltd. (Excludes one thousand shares which, although registered in the name of the Chiba Bank, Ltd. on the shareholder list, are not actually owned by the Bank.) As a regional financial institution based in Chiba Prefecture, Chiba Bank Group recognizes that *1 Rounded down to the nearest thousand *2 Rounded down to two decimal places its mission is to “contribute to the sustainable development of regional economies through the *3 The trade name of Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Insurance Inc. -

Pdf/Rosen Eng.Pdf Rice fields) Connnecting Otsuki to Mt.Fuji and Kawaguchiko

Iizaka Onsen Yonesaka Line Yonesaka Yamagata Shinkansen TOKYO & AROUND TOKYO Ōu Line Iizakaonsen Local area sightseeing recommendations 1 Awashima Port Sado Gold Mine Iyoboya Salmon Fukushima Ryotsu Port Museum Transportation Welcome to Fukushima Niigata Tochigi Akadomari Port Abukuma Express ❶ ❷ ❸ Murakami Takayu Onsen JAPAN Tarai-bune (tub boat) Experience Fukushima Ogi Port Iwafune Port Mt.Azumakofuji Hanamiyama Sakamachi Tuchiyu Onsen Fukushima City Fruit picking Gran Deco Snow Resort Bandai-Azuma TTOOKKYYOO information Niigata Port Skyline Itoigawa UNESCO Global Geopark Oiran Dochu Courtesan Procession Urabandai Teradomari Port Goshiki-numa Ponds Dake Onsen Marine Dream Nou Yahiko Niigata & Kitakata ramen Kasumigajo & Furumachi Geigi Airport Urabandai Highland Ibaraki Gunma ❹ ❺ Airport Limousine Bus Kitakata Park Naoetsu Port Echigo Line Hakushin Line Bandai Bunsui Yoshida Shibata Aizu-Wakamatsu Inawashiro Yahiko Line Niigata Atami Ban-etsu- Onsen Nishi-Wakamatsu West Line Nagaoka Railway Aizu Nō Naoetsu Saigata Kashiwazaki Tsukioka Lake Itoigawa Sanjo Firework Show Uetsu Line Onsen Inawashiro AARROOUUNNDD Shoun Sanso Garden Tsubamesanjō Blacksmith Niitsu Takada Takada Park Nishikigoi no sato Jōetsu Higashiyama Kamou Terraced Rice Paddies Shinkansen Dojo Ashinomaki-Onsen Takashiba Ouchi-juku Onsen Tōhoku Line Myoko Kogen Hokuhoku Line Shin-etsu Line Nagaoka Higashi- Sanjō Ban-etsu-West Line Deko Residence Tsuruga-jo Jōetsumyōkō Onsen Village Shin-etsu Yunokami-Onsen Railway Echigo TOKImeki Line Hokkaid T Kōriyama Funehiki Hokuriku -

![[Bus] Meguro-Dori T Okyu Meguro Line JR Y Amanote Line Y Amate-Dori Meguro Station Access](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7153/bus-meguro-dori-t-okyu-meguro-line-jr-y-amanote-line-y-amate-dori-meguro-station-access-287153.webp)

[Bus] Meguro-Dori T Okyu Meguro Line JR Y Amanote Line Y Amate-Dori Meguro Station Access

To Shibuya To Meguroshinbashi Ootorijinjamae Mos Burger Meguro-dori West exit Meguro Maruetsu Police Station Ootori shrine box My Basket drug store RECODS Liquor Seven-eleven West exit shop Gyoninzaka The 4th parking lot (Toll parking, Rakan reservation is needed.) ⑨ Meguro Gajoen Front entrance *Refer to attached map Temple Meguro Arco Tower Station Atre Naboku Line Sunkus Mita Line Rakan Tokyu Meguro Line Kaikan Megurofudo The 3rd parking lot Meguro Line Tokyu Line JR Yamanote The 2nd parking lot (Toll parking, Kinokuniya reservation is needed.) HQ Daikokuya Megurofudosonmae dori Kamurozakashita Super Ozeki Yamate-dori Matsuya Florist's Shinagawa To Fudomae Station Access [Bus] A short walk from “Fudoson Sando” bus stop of Route Shibuya 41 [Train] bound for Ooimachi Station of Tokyu Bus. 10 minute walk from JR/Tokyo Metro Meguro Station (Please take Tokyu Bus from the south exit of Shibuya Station 7 minute walk from Tokyu Line Fudomae Station. or from Tokyu Toyoko Line Nakameguro Station.) [IMAGE STUDIO 109, INC 2-24-12, Shimomeguro, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, 153-0064 (MEGURO CUE building) Studio department Post production department □CCTV department General affairs department TEL.03-5436-9109 FAX.03-3494-8871 Parking lot guide To Nakameguro Ootorijinjamae Meguro-dori Meguroshinbashi Maruetsu Ootori shrine Yamate-dori drug store RECODS Yanagi-dori Meguro River Rakan Temple Sunkus The 3rd parking lot (Reservation is needed.) The 3rd parking lot *Refer to attached map (Reservation is needed.) Multistory car park Megurofudo Daikokuya Kinokuniya HQ The 2nd parking lot To Gotanda [About parking lots] If all the parking lots shown above are full, please use other parking facilities nearby. -

Seasonal Variability of the Red Tide-Forming Heterotrophic Dino

Plankton Benthos Res 8(1): 9–30, 2013 Plankton & Benthos Research © The Plankton Society of Japan Seasonal variability of the red tide-forming heterotrophic dinoflagellate Noctiluca scintillans in the neritic area of Sagami Bay, Japan: its role in the nutrient-environment and aquatic ecosystem 1, 1 1 2,3 KOICHI ARA *, SACHIKO NAKAMURA , RYOTO TAKAHASHI , AKIHIRO SHIOMOTO 1 & JURO HIROMI 1 D epartment of Marine Science and Resources, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 252– 0880, Japan 2 N ational Research Institute of Fisheries Science, Fisheries Research Agency, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa 236– 8648, Japan 3 P resent Address: Department of Aquatic Bioscience, Faculty of Bioindustry, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Abashiri, Hokkaido 099–2493, Japan Received 19 June 2012; Accepted 14 January 2013 Abstract: The role of the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Noctiluca scintillans in affecting the nutrient-environment and aquatic ecosystem was investigated in the neritic area of Sagami Bay, Kanagawa, Japan, from January 2002 to De- cember 2006, based on abundance, intracellular nutrient content, excretion rate and response of phytoplankton (dia- toms) to enrichment of nutrients extracted from N. scintillans cells. Seasonal variations in abundance and vertical distribution of N. scintillans were significantly related to the physical structure of the water column, water tempera- ture, chlorophyll a and primary productivity. Intracellular nutrient contents, except for Si(OH)4-Si, revealed clear sea- sonal fluctuations, which were significantly correlated to cell size variations. Thalassiosira rotula increased to higher + cell abundances at higher concentrations of nutrients, which were extracted from N. scintillans cells. NH4 -N and 3– + PO4 -P excretion rates were much higher during the first 1–3 h, and decreased rapidly with time. -

Meguro Walking Map

Meguro Walking Map Meguro Walking Map Primary print number No. 31-30 Published February 2, 2020 December 6, 2019 Published by Meguro City Edited by Health Promotion Section, Health Promotion Department; Sports Promotion Section, Culture and Sports Department, Meguro City 2-19-15 Kamimeguro, Meguro City, Tokyo Phone 03-3715-1111 Cooperation provided by Meguro Walking Association Produced by Chuo Geomatics Co., Ltd. Meguro City Total Area Course Map Contents Walking Course 7 Meguro Walking Courses Meguro Walking Course Higashi-Kitazawa Sta. Total Area Course Map C2 Walking 7 Meguro Walking Courses P2 Course 1: Meguro-dori Ave. Ikenoue Sta. Ke Walk dazzling Meguro-dori Ave. P3 io Inok Map ashira Line Komaba-todaimae Sta. Course 2: Komaba/Aobadai area Shinsen Sta. Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji P7 0 100 500 1,000m Awas hima-dori St. 3 Course 3: Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area Kyuyamate-dori Ave. Walk the 1964 Tokyo Olympics P11 2 Komaba/Aobadai area Walk the ties between Meguro and Fuji Shibuya City Tamagawa-dori Ave. Course 4: Himon-ya/Meguro-honcho area Ikejiri-ohashi Sta. Meguro/Shimomeguro area Walk among the history and greenery of Himon-ya P15 5 Walk among Edo period townscape Daikan-yama Sta. Course 5: Meguro/Shimomeguro area Tokyu Den-en-toshi Line Walk among Edo period townscape P19 Ebisu Sta. kyo Me e To tro Hibiya Lin Course 6: Yakumo/Midorigaoka area Naka-meguro Sta. J R Walk a green road born from a culvert P23 Y Yutenji/Chuo-cho area a m 7 Yamate-dori Ave. a Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n o Course 7: Yutenji/Chuo-cho area t e L Meguro City Office i Walk Yutenji and the vestiges of the old horse track n P27 e / S 2 a i k Minato e y Kakinokizaka/Higashigaoka area o in City Small efforts, L Yutenji Sta. -

Edo-Mae Chiba NORI

Once in a lifetime deliciousness A little luxury Always Chiba NORI Charm and character of Edo-mae Chiba NORI What makes NORI so delicious? The crispness? The tenderness? We hear many different opinions, but above all, we believe “Flavor and fragrance” are the most Edo-mae important! Chiba NORI’s pursuit of “Flavor and (Tok yo ) (region) fragrance” mean research and efforts are being made daily for quality improvement. The high quality of the fragrance of Chiba NORI is guaranteed; and regarding the Flavor, it melts on the tongue and UMAMI taste Chiba NORI spreads throughout your mouth. Chiba prefecture Dried seaweed sheet ( ) ( ) Chiba prefecture Mascot character The key to the Flavor is the “UMAMI component” of NORI. As in Konbu (Kelp), NORI contains a rich supply of the UMAMI component of glutamine acid. Also, in the process of drying raw NORI, Inosine CHI-BA+KUN acid is said to become more abundant, and the combination of Glutamine acid and Inosine acid create an “UMAMI synergy” and an even richer Flavor is born. Strength of UMAMI UMAMI One of the points of commitment during the production of Chiba synergy NORI is “changing the nets frequently”. By the NORI fishermen spending time changing the nets, freshly sprouted NORI can be Continuing to preserve cultivated more frequently, allowing for cultivation of a higher quality and tender NORI. “Edo-region Chiba NORI” will continue to the Edo (Tokyo)-mae(region) evolve and pursue even further delicious Flavor, while appreciating the blessings of nature such as the abundant nutrients poured into tradition for 200 years Tokyo Bay from the Kanto Plain and the tranquil tidal flats suitable Inosine Glutamine Effect acid + acid = multiplied for cultivating NORI. -

Source Model of the 1703 Genroku Kanto Earthquake Tsunami Based on Historical Documents and Numerical Simulations: Modeling of A

Yanagisawa and Goto Earth, Planets and Space (2017) 69:136 DOI 10.1186/s40623-017-0713-4 FULL PAPER Open Access Source model of the 1703 Genroku Kanto earthquake tsunami based on historical documents and numerical simulations: modeling of an ofshore fault along the Sagami Trough Hideaki Yanagisawa1* and Kazuhisa Goto2 Abstract The 1703 Genroku Kanto earthquake and the resulting tsunami caused catastrophic damage in the Kanto region of Japan. Previous modeling of the 1703 earthquake applied inversion analyses of the observed terrestrial crustal deformations along the coast of the southern Boso Peninsula and revealed that the tsunami was generated along the Sagami Trough. Although these models readily explained the observed crustal deformation, they were unable to model an ofshore fault along the Sagami Trough because of difculties related to the distance of the ofshore fault from the shoreline. In addition, information regarding the terrestrial crustal deformation is insufcient to constrain such inverted models. To model an ofshore fault and investigate the triggering of large tsunamis of the Pacifc coast of the Boso Peninsula, we studied historical documents related to the 1703 tsunami from Choshi City. Based on these historical documents, we estimated tsunami heights of 5.9, 11.4–11.7, 7.7, 10.8 and 4.8 m for the Choshi City regions of Isejiga-ura, Kobatake-ike, Nagasaki, Tokawa and≥ Na’arai, respectively.≥ Although≥ previous studies assumed that the tsunami heights ranged from 3.0 to 4.0 m in Choshi City, we revealed that the tsunami reached heights exceeded 11 m in the city. We further studied the fault model of the 1703 Genroku Kanto earthquake numerically using the newly obtained tsunami height data. -

Tokyo Station

Tokyo Station Taxi Nihombashi Tiket Gate Yaesu Central Entrance (Tokaido & San-yo Shinkansen) JR Bus (JR Bus) Keiyo Line Waiting room Yaesu ( ) Central Waiting room Yaesu South Underground Ticket Gate Yaesu North Ticket Gate 19 Ticket Gate 19 Yaesu Ticket Gate to Keiyo Line Station 18 18 (Underground) 17 17 16 16 15 15 14 14 WWaitingaiting room WWaitingaiting room 23 23 22 Nursery 22 21 21 20 20 10 9 Japan Rail Pass 8 Exchange Corner 7 Nihombashi Tiket Gate 6 (Tohoku, Yamagata, Akita 5 Joetsu & Nagano Shinkansen) 4 2 3 1 Marunouchi North Ticket Gate (B1) Taxi (B3) Marunouchi Central Ticket Gate Marunouchi South Ticket Gate Underground Marunouchi Underground North Marunouchi Ticket Gate South Ticket Gate (B1) ↓ (B4) 1 2 3 Underground 4 (B5) 1 2 Marunouchi 3 4 Central Sobu Line Ticket Gate Platform (Basement Level 5) (B4) Transfer Information Marunouchi Ticket Gate to Keiyo Line Station 1 2 Chuo Line for Takao Sobu Line(Underground Platform) (Underground) 3 Keihin-Tohoku Line for Omiya 1 2 3 4 Sobu Line,Yokosuka Line for Boso(Rapid-service Train) 4 Yamanote Line Inner Tracks for Ueno for Choshi,Kashima-Jingu(Limited Express) 5 Yamanote Line Outer Tracks for Shinagawa "Narita Express" for Narita Airport < as of April 2012 > 6 Keihin-Tohoku Line for Ofuna Keiyo Line(Underground Platform) 7 8 Tokaido Line 1 2 3 4 For Boso(Limited Express,Rapid-service Train) 9 10 Tokaido Line(Limited Express) Keiyo Line for Maihama,Soga Shinkansen Musashino Line for Maihama,Nishi-Funabashi 14 19 Tokaido,San-yo Shinkansen 20 23 Tohoku,Yamagata,Akita,Joetsu,Nagano Shinkansen Coin-operated Lockers JR Reservation Ticket Offices View Plaza Rent a Car ( "Midori-no-madoguchi") (Extra large/large available) Coin-operated Lockers Ticket Vending Machines Elevator Information Center (Midsize/standard only) Facility for the Restroom Handicapped Escalator Ticket Gate 1 Track (Platform) [ note! ] : JAPAN RAIL PASS, JR EAST PASS exchange office : JR EAST PASS sales office *A JAPAN RAIL PASS cannnot be purchased inside Japan. -

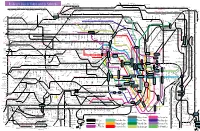

Railway Lines in Tokyo and Its Suburbs

Minami-Sakurai Hasuta Shin-Shiraoka Fujino-Ushijima Shimizu-Koen Railway Lines in Tokyo and its Suburbs Higashi-Omiya Shiraoka Kuki Kasukabe Kawama Nanakodai Yagisaki Obukuro Koshigaya Atago Noda-Shi Umesato Unga Edogawadai Hatsuisi Toyoshiki Fukiage Kita-Konosu JR Takasaki Line Okegawa Ageo Ichinowari Nanasato Iwatsuki Higashi-Iwatsuki Toyoharu Takesato Sengendai Kita-Koshigaya Minami-Koshigaya Owada Tobu-Noda Line Kita-Kogane Kashiwa Abiko Kumagaya Gyoda Konosu Kitamoto Kitaageo Tobu Nota Line Toro Omiya-Koen Tennodai Miyahara Higashi-Urawa Higashi-Kawaguchi JR Musashino Line Misato Minami-Nagareyama Urawa Shin-Koshigaya Minami- Kita- Saitama- JR Tohoku HonsenKita-Omiya Warabi Nishi-Kawaguchi Kawaguchi Kashiwa Kashiwa Hon-Kawagoe Matsudo Shin- Gamo Takenozuka Yoshikawa Shin-Misato Shintoshin Nishi-Arai Umejima Mabashi Minoridai Gotanno Yono Kita-Urawa Minami-Urawa Kita-Akabane Akabane Shinden Yatsuka Shin- Musashiranzan Higashi-Jujo Kita-Matsudo Shinrin-koenHigashi-MatsuyamaTakasaka Omiya Kashiwa Toride Yono Minami- Honmachi Yono- Matsubara-Danchi Shin-Itabashi Minami-FuruyaJR Kawagoe Line Musashishi-Urawa Kita-Toda Toda Toda-Koen Ukima-Funato Kosuge JR Saikyo Line Shimo Matsudo Kita-Sakado Kita- Shimura- Akabane-Iwabuchi Soka Masuo Ogawamachi Naka-Urawa Takashimadaira Shiden Matsudo- Yono Nishi-Takashimadaira Hasune Sanchome Itabashi-Honcho Oji Kita-senju Kami- Myogaku Sashiogi Nisshin Nishi-Urawa Daishimae Tobu Isesaki Line Kita-Ayase Kanamachi Hongo Shimura- Jujo Oji-Kamiya Oku Sakasai Yabashira Kawagoe Shingashi Fujimino Tsuruse