William Vassall and Dissent in Early Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

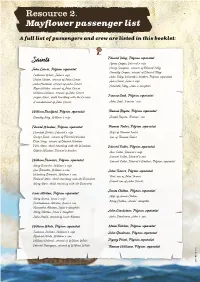

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects "Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University Recommended Citation Witkowski, Monica C., ""Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 27. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/27 “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 by Monica C. Witkowski A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University, 2010 What was the legal status of women in early colonial Maryland? This is the central question answered by this dissertation. Women, as exemplified through a series of case studies, understood the law and interacted with the nascent Maryland legal system. Each of the cases in the following chapters is slightly different. Each case examined in this dissertation illustrates how much independent legal agency women in the colony demonstrated. Throughout the seventeenth century, Maryland women appeared before the colony’s Provincial and county courts as witnesses, plaintiffs, defendants, and attorneys in criminal and civil trials. Women further entered their personal cattle marks, claimed land, and sued other colonists. This study asserts that they improved their social standing through these interactions with the courts. By exerting this much legal knowledge, they created an important place for themselves in Maryland society. Historians have begun to question the interpretation that Southern women were restricted to the home as housewives and mothers. -

Colonial America

COLONIAL AMERICA 1651 DOCUMENT SIGNED BY TIMOTHY HATHERLY, WITCH TRIAL MAGISTRATE AND MASSACHUSETTS MERCHANT ADVENTURER WHO FINANCED THE BAY COLONY GOVERNOR THOMAS PRENCE SIGNS A COLONY AT PLYMOUTH 1670 DEPOSITION * 1 [COLONIAL PLYMOUTH] TIMOTHY HATHERLY was * 2 one of the Merchant Adventurers of London who financed the [COLONIAL PLYMOUTH] THOMAS PRENCE: Governor colony at Plymouth, Massachusetts after obtaining a patent from Massachusetts Bay colony. Arrived at Plymouth Colony on the “For- King James covering all of the Atlantic coast of America from the tune” in 1621. He was one of the first settlers of Nansett, or grant to the Virginia company on the south, to and including New- Eastham, was chosen the first governor of Governor of Massachu- foundland. Hatherly was one of the few Adventurers to actually setts Bay Colony in 1633. serving until 1638, and again from 1657 till settle in America. He arrived in 1623 on the ship Ann, then returned 1673, and was an assistant in 1635-’7 and 1639-’57. Governor Prence to England in 1625. In 1632, he came back to Plymouth and in 1637 also presided over a witch trial in 1661 and handled it “sanely and was one of the recipients of a tract of land at Scituate. Before 1646, with reason.” He also presided over the court when the momen- Hatherly had bought out the others and had formed a stock com- tous decision was made to execute a colonist who had murdered an pany, called the “Conihasset Partners.” Scituate was part of the Ply- Indian. He was an impartial magistrate, was distinguished for his mouth Colony; it was first mentioned in William Bradford’s writ- religious zeal, and opposed those that he believed to be heretics, ings about 1634. -

Winslows: Pilgrims, Patrons, and Portraits

Copyright, The President and Trustees of Bowdoin College Brunswick, Maine 1974 PILGRIMS, PATRONS AND PORTRAITS A joint exhibition at Bowdoin College Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Organized by Bowdoin College Museum of Art Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/winslowspilgrimsOObowd Introduction Boston has patronized many painters. One of the earhest was Augustine Clemens, who began painting in Reading, England, in 1623. He came to Boston in 1638 and probably did the portrait of Dr. John Clarke, now at Harvard Medical School, about 1664.' His son, Samuel, was a member of the next generation of Boston painters which also included John Foster and Thomas Smith. Foster, a Harvard graduate and printer, may have painted the portraits of John Davenport, John Wheelwright and Increase Mather. Smith was commis- sioned to paint the President of Harvard in 1683.^ While this portrait has been lost, Smith's own self-portrait is still extant. When the eighteenth century opened, a substantial number of pictures were painted in Boston. The artists of this period practiced a more academic style and show foreign training but very few are recorded by name. Perhaps various English artists traveled here, painted for a time and returned without leaving a written record of their trips. These artists are known only by their pictures and their identity is defined by the names of the sitters. Two of the most notable in Boston are the Pierpont Limner and the Pollard Limner. These paint- ers worked at the same time the so-called Patroon painters of New York flourished. -

MASSACHUSETTS: Or the First Planters of New-England, the End and Manner of Their Coming Thither, and Abode There: in Several EPISTLES (1696)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Joshua Scottow Papers Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1696 MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696) John Winthrop Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony Thomas Dudley Deputy Governor, Massachusetts Bay Colony John Allin Minister, Dedham, Massachusetts Thomas Shepard Minister, Cambridge, Massachusetts John Cotton Teaching Elder, Church of Boston, Massachusetts See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow Part of the American Studies Commons Winthrop, John; Dudley, Thomas; Allin, John; Shepard, Thomas; Cotton, John; Scottow, Joshua; and Royster,, Paul Editor of the Online Electronic Edition, "MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New- England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES (1696)" (1696). Joshua Scottow Papers. 7. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/scottow/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joshua Scottow Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors John Winthrop; Thomas Dudley; John Allin; Thomas Shepard; John Cotton; Joshua Scottow; and Paul Royster, Editor of the Online Electronic Edition This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ scottow/7 ABSTRACT CONTENTS In 1696 there appeared in Boston an anonymous 16mo volume of 56 pages containing four “epistles,” written from 66 to 50 years earlier, illustrating the early history of the colony of Massachusetts Bay. -

"In the Pilgrim Way" by Linda Ashley, A

In the Pilgrim Way The First Congregational Church, Marshfield, Massachusetts 1640-2000 Linda Ramsey Ashley Marshfield, Massachusetts 2001 BIBLIO-tec Cataloging in Publication Ashley, Linda Ramsey [1941-] In the pilgrim way: history of the First Congregational Church, Marshfield, MA. Bibliography Includes index. 1. Marshfield, Massachusetts – history – churches. I. Ashley, Linda R. F74. 2001 974.44 Manufactured in the United States. First Edition. © Linda R. Ashley, Marshfield, MA 2001 Printing and binding by Powderhorn Press, Plymouth, MA ii Table of Contents The 1600’s 1 Plimoth Colony 3 Establishment of Green’s Harbor 4 Establishment of First Parish Church 5 Ministry of Richard Blinman 8 Ministry of Edward Bulkley 10 Ministry of Samuel Arnold 14 Ministry of Edward Tompson 20 The 1700’s 27 Ministry of James Gardner 27 Ministry of Samuel Hill 29 Ministry of Joseph Green 31 Ministry of Thomas Brown 34 Ministry of William Shaw 37 The 1800’s 43 Ministry of Martin Parris 43 Ministry of Seneca White 46 Ministry of Ebenezer Alden 54 Ministry of Richard Whidden 61 Ministry of Isaac Prior 63 Ministry of Frederic Manning 64 The 1900’s 67 Ministry of Burton Lucas 67 Ministry of Daniel Gross 68 Ministry of Charles Peck 69 Ministry of Walter Squires 71 Ministry of J. Sherman Gove 72 Ministry of George W. Zartman 73 Ministry of William L. Halladay 74 Ministry of J. Stanley Bellinger 75 Ministry of Edwin C. Field 76 Ministry of George D. Hallowell 77 Ministry of Vaughn Shedd 82 Ministry of William J. Cox 85 Ministry of Robert H. Jackson 87 Other Topics Colonial Churches of New England 92 United Church of Christ 93 Church Buildings or Meetinghouses 96 The Parsonages 114 Organizations 123 Sunday School and Youth 129 Music 134 Current Officers, Board, & Committees 139 Gifts to the Church 141 Memorial Funds 143 iii The Centuries The centuries look down from snowy heights Upon the plains below, While man looks upward toward those beacon lights Of long ago. -

Genealogy Edward Wins

GEN EALOGY E DWA R D WI N S LOW TH E MAYFLOWE R A N D H I S D E S C E N D A N T S FROM 1 620 TO 1 865 MARIA WHITMAN B RYANT D AUGHT E R OF ELI"AB ETH WIN SLOW A ND (JUDGE ) KILB ORN WHITMAN F PE BR KE MASS . O M O , C o pyright 1 91 5 by Herbe rt Pelh am B ry ant A ll Right s Reserved A NTHONY So ns, ' Ne w B e o Mass df rd , . , U . (3 p r y P R E F A C E These biographies are gathered and arranged for the use Of the generations in the direct line Of descent from Edward Winslow as they , n i n i will i ev tably be dispersed in the future , givi g nto their possession , in a compact form , this knowledge Of the incidents in the lives of those who preceded them . They are facts reliable and without embellishment . Adopting the sentim ents expressed in the introduction to the history Of the Otis family by Horatio N . Otis member of the New England Historical and Genealogical Society ,of New York we quote as follows , It i s to be regretted while sketching the external circumstances Of some , the chroniclers , that such a man was born , died , and ran through such a circle Of honors , etc . , that we cannot more carefully trace the history Of mind, those laws which govern in the transmission fi of physical and mental quali cation . -

Life in the New England Colonies

Life in the New England Colonies The New England colonies include Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island. The lifestyle of New England’s people was greatly impacted by both its geography and climate. New England’s economy depended on the environment. Its location near the Atlantic Ocean along a jagged coastline determined how people made a living. People in New England made money through fishing, whaling, shipbuilding, trading in its port cities and providing naval supplies. One of the busiest port cities was Boston. People in New England could not make a living from farming because most of the land was not suited to farming due to the hilly terrain and rocky soil. The nature of the soil was partially caused by the Appalachian Mountains. Another factor that made farming for profit difficult was climate; New England experienced moderate summers and cold winters. The growing season was simply too short to make farming profitable and most farms were small family ones. So rather than farming, many people not involved in industries involving the water were either skilled craftsman or shopkeepers. Towns and villages were very important in the daily lives of New Englanders. Their social lives revolved around village events and attending church. The Sabbath or Sunday was a high point of the week. Work was not allowed and it provided an opportunity to visit one another. Many of the New England colonies were founded by religious reformers and separatists searching for religious freedom. Civic events were also central to New England life. Town meetings determined answers to important questions about running the colony. -

Colonial America Saturdays, August 22 – October 10 9:30 AM to 12:45 PM EST

Master of Arts in American History and Government Ashland University AHG 603 01A Colonial America Saturdays, August 22 – October 10 9:30 AM to 12:45 PM EST Sarah Morgan Smith and David Tucker Course focus: This course focuses on the development of an indigenous political culture in the British colonies. It pays special attention to the role of religion in shaping the American experience and identity of ‘New World’ inhabitants, as well as to the development of representative political institutions and how these emerged through the confrontation between colonists and King and proprietors. Learning Objectives: To increase participants' familiarity with and understanding of: 1. The reasons for European colonization of North America and some of the religious and political ideas that the colonists brought with them, as well as the ways those ideas developed over the course of the 17th-18th centuries 2. The “first contact” between native peoples and newcomers emphasizing the world views of Indians and Europeans and the way each attempted to understand the other. 3. The development of colonial economies as part of the Atlantic World, including servitude and slavery and the rise of consumerism. 4. Religion and intellectual life and the rise of an “American” identity. Course Requirements: Attendance at all class sessions. Presentation/Short Paper: 20% o Each student will be responsible for helping to guide our discussion during one session of the courses by making a short presentation to the class and developing additional focus/discussion questions related to the readings (beyond those listed in the syllabus). On the date of their presentation, the student will also submit a three page paper and a list of (additional) discussion questions. -

REVEREND WILLIAM NOYES, Born, ENGLAND, 1568

DESCENDANTS OF REVEREND WILLIAM NOYES, BoRN, ENGLAND, 1568, IN DIRECT LINE TO LAVERNE W. NOYES, AND FRANCES ADELIA NOYES-GIFFEN. ALLIED FAMILIES OF STANTON. LORD. SANFORD. CODDINGTON. THOMPSON. FELLOWS. HOLDREDGE. BERRY. SAUNDERS. CLARKE. JESSUP. STUDWELL. RUNDLE. FERRIS. LOCKWOOD. PUBLISHED BY LA VERNE W. NO-YES, CHICAGO; ILLINOIS. 1900. PRESS OF 52 W. JACJCSON ST. LAV ERSE W. N oYi-:s. ~u9fi persona[ interest, and curiosity, as to liis antecedents, f lie pu6frslier of tliis 6ook lias 9atliered, and caused to 6e 9atliered, tlie statistics lierein contained. $ecause flieg Cfl)ere so dijficaft to coffed, as CftJe{{ as to figlifen tlie task of of liers of liis ~ind . red cwlio mag liave a simifar curious interest in ancesfrg, lie decided to print f.iem, and liopes tliat tlieg mag prove of maferiaf assistance to otliers. e&af/erne W. J2oges. CHICAGO, 1900. NOYES FAMILY. Reverend William Noyes was born in England during the year 1568. He matriculated at University College, Oxford, 15 November, 1588, at the age of twenty years, and was graduated B. A., 31 May, 1592. He was Rector of the Parish of Choulderton in Wiltshire, situated between Amesbury in Wiltshire and Andover in Hampshire, and eleven mile~ from Salisbury, which contains the great Salisbury Cathedral, built in the year 1220 A. D., whose lofty tower overlooks the dead Roman city of Sarum and '' Stonehenge," the ruins of the won derful pre-historic temple of the ancient Celtic Druids, in the midst of Salisbury Plain. The register of the Diocese shows that he officiated in the Parish from 1602 to 1620, at which time he resigned. -

Congregational History Society Magazine

ISSN 0965–6235 Congregational History Society Magazine Volume 8 Number 3 Spring 2017 ISSN 0965–6235 THE CONGREGATIONAL HISTORY SOCIETY MAGAZINE Volume 8 No 3 Spring 2017 Contents Editorial 2 News and Views 2 Correspondence and Feedback 4 Secretary’s notes Unity in Diversity—two anniversaries re-visited Richard Cleaves 6 ‘Seditious sectaries’: The Elizabeth and Jacobean underground church Stephen Tomkins 11 History in Preaching Alan Argent 23 ‘Occupying a Proud Position in the City’: Winchester Congregational Church in the Edwardian Era 1901–14 Roger Ottewill 41 Reviews 62 All rights are reserved: no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the permission of the Congregational History Society, as given by the editor. Congregational History Society Magazine, Vol. 8, No 3, 2017 1 EDITORIAL We welcome Stephen Tomkins to our pages. He gives here a consideration of the Elizabethan separatists, in this 450th anniversary year of the detention by the sheriff’s officers of some members of the congregation meeting then at Plumbers Hall, London. In addition this issue of our CHS Magazine includes the promised piece on history and preaching to which many of our readers in this country and abroad contributed. Although this is merely a qualitative study, we hope that it may offer support to those who argue for the retention of specialist historians within ministerial training programmes. Certainly its evidence suggests that those who dismiss history as of little or no use to the preacher will lack support from many practitioners. -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies.