Developments in Mathematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Short CV For: Alexander Lubotzky

Short CV for: Alexander Lubotzky Personal: • born 28/6/56 in Israel. • Married to Yardenna Lubotzky (+ six children) Studies: • B. Sc., Mathematics, Bar-Ilan University, 1975. • Ph.D., Mathematics, Bar-Ilan University, 1979. (Supervisor: H. Fussten- berg, Thesis: Profinite groups and the congruence subgroup problem.) Employment: • 1982 - current: Institute of Mathematics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Professor - Holding the Maurice and Clara Weil Chair in Mathematics • 1999-current: Adjunct Professor at Yale University • Academic Year 2005-2006: Leading a year long research program at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton on \Lie Groups, Repre- sentations and Discrete Mathematics." Previous Employment: • Bar-Ilan University, 1976-1982 • Israeli Defense Forces, 1977-1982 • Member of the Israeli Parliament (Knesset), 1996-1999 Visiting Positions: • Yale University (several times for semesters or years) • Stanford University (84/5) • University of Chicago (92/3) • Columbia University (Elenberg visiting Professor Fall 2000) 1 • Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton (2005/6) Main prizes and Academic Honors: • Elected as Foreign Honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences • Ferran Sunyer i Balaguer Prize twice: 1993 for the book: \Discrete Groups, Expanding Groups and Invariant Measures", Prog. in math 125, Birkhauser 1994, and in 2002 joint with Professor Dan Segal from Oxford for the book \Subgroup Growth", Prog. in Math. 212, Birkhauser 2003. • The Rothschild Prize 2002. • The Erdos Prize in 1991. Editorial work: • Israel Journal of Mathematics (1990-now) • Journal of Algebra (1990-2005) • GAFA (1990-2000) • European Journal of Combinatorics • Geometric Dedicata • Journal of the Glasgow Mathematical Scientists Books and papers: • Author of 3 books and over 90 papers. -

Conference Celebrating the 70Th Birthday of Prof. Krzysztof M. Pawa Lowski 11–13 January 2021, Online Conference Via Zoom

kpa70 Conference celebrating the 70th birthday of Prof. Krzysztof M. Pawa lowski 11{13 January 2021, Online conference via Zoom https://kpa70.wmi.amu.edu.pl/ Invited Speakers: • William Browder (Princeton University), • Sylvain Cappell (New York University), • James F. Davis (Indiana University Bloomington), • Bogus law Hajduk (University of Warmia and Mazury), • Jaros law K¸edra(University of Aberdeen), • Mikiya Masuda (Osaka City University), • Masaharu Morimoto (Okayama University), • Robert Oliver (Paris University 13), • Taras Panov (Moscow State University), • J´ozefPrzytycki (George Washington University and University of Gda´nsk), • Toshio Sumi (Kyushu University). Organizers: • Marek Kaluba, • Wojciech Politarczyk, • Bartosz Biadasiewicz, • Lukasz Michalak, • Piotr Mizerka, • Agnieszka Stelmaszyk-Smierzchalska.´ i Monday, January 11 Time Washington Warsaw Tokyo 6:45 { 12:45 { 20:45 { Opening 7:00 13:00 21:00 Mikiya Masuda, 7:00 { 13:00 { 21:00 { Invariants of the cohomology rings of the permutohedral 7:45 13:45 21:45 varieties Taras Panov, 8:00 { 14:00 { 22:00 { Holomorphic foliations and complex moment-angle 8:45 14:45 22:45 manifolds 9:15 { 15:15 { 23:15 { Robert Oliver, 10:00 16:00 00:00 The loop space homology of a small category J´ozefH. Przytycki, 10:15 { 16:15 { 00:15 { Adventures of Knot Theorist: 11:00 17:00 01:00 from Fox 3-colorings to Yang-Baxter homology{ 5 years after Pozna´ntalks Tuesday, January 12 Time Washington Warsaw Tokyo Piotr Mizerka, 6:20 { 12:20 { 20:20 { New results on one and two fixed point actions 6:45 12:45 20:45 on spheres 7:00 { 13:00 { 21:00 { Masaharu Morimoto, 7:45 13:45 21:45 Equivariant Surgery and Dimension Conditions 8:00 { 14:00 { 22:00 { Toshio Sumi, 8:45 14:45 22:45 Smith Problem and Laitinen's Conjecture Sylvain Cappell, 9:15 { 15:15 { 23:15 { Fixed points of G-CW-complex with prescribed 10:00 16:00 00:00 homotopy type 10:15 { 16:15 { 00:15 { James F. -

A Group Theoretic Characterization of Linear Groups

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector JOURNAL OF ALGEBRA 113, 207-214 (1988) A Group Theoretic Characterization of Linear Groups ALEXANDER LUBOTZKY Institute qf Mathematics, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel 91904 Communicated by Jacques Tits Received May 12, 1986 Let r be a group. When is f linear? This is an old problem. The first to study this question systematically was Malcev in 1940 [M], who essen- tially reduced the problem to finitely generated groups. (Note that a finitely generated group is linear over some field of characteristic zero if and only if it can be embedded in CL,(C) for some n.) Very little progress was made since that paper of Malcev, although, as linear groups are a quite special type of group, many necessary conditions were obtained, e.g., r should be residually finite and even virtually residually-p for almost all primes p, f should be virtually torsion free, and if not solvable by finite it has a free non-abelian subgroup, etc. (cf. [Z]). Of course, none of these properties characterizes the finitely generated linear groups over @. In this paper we give such a characterization using the congruence structure of r. First some definitions: For a group H, d(H) denotes the minimal number of generators for H. DEFINITION. Let p be a prime and c an integer. A p-congruence structure (with a bound c) for a group r is a descending chain of finite index normal subgroups of r = N, 2 N, 2 N, z . -

A Unified Approach to Three Themes in Harmonic Analysis ($1^{St} $ Part)

A UNIFIED APPROACH TO THREE THEMES IN HARMONIC ANALYSIS (I & II) (I) THE LINEAR HILBERT TRANSFORM AND MAXIMAL OPERATOR ALONG VARIABLE CURVES (II) CARLESON TYPE OPERATORS IN THE PRESENCE OF CURVATURE (III) THE BILINEAR HILBERT TRANSFORM AND MAXIMAL OPERATOR ALONG VARIABLE CURVES VICTOR LIE In loving memory of Elias Stein, whose deep mathematical breadth and vision for unified theories and fundamental concepts have shaped the field of harmonic analysis for more than half a century. arXiv:1902.03807v2 [math.AP] 2 Oct 2020 Date: October 5, 2020. Key words and phrases. Wave-packet analysis, Hilbert transform and Maximal oper- ator along curves, Carleson-type operators in the presence of curvature, bilinear Hilbert transform and maximal operators along curves, Zygmund’s differentiation conjecture, Car- leson’s Theorem, shifted square functions, almost orthogonality. The author was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DMS- 1500958. The most recent revision of the paper was performed while the author was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DMS-1900801. 1 2 VICTOR LIE Abstract. In the present paper and its sequel [63], we address three rich historical themes in harmonic analysis that rely fundamentally on the concept of non-zero curvature. Namely, we focus on the boundedness properties of (I) the linear Hilbert transform and maximal operator along variable curves, (II) Carleson-type operators in the presence of curvature, and (III) the bilinear Hilbert transform and maximal operator along variable curves. Our Main Theorem states that, given a general variable curve γ(x,t) in the plane that is assumed only to be measurable in x and to satisfy suitable non-zero curvature (in t) and non-degeneracy conditions, all of the above itemized operators defined along the curve γ are Lp-bounded for 1 <p< ∞. -

Counting Arithmetic Lattices and Surfaces

ANNALS OF MATHEMATICS Counting arithmetic lattices and surfaces By Mikhail Belolipetsky, Tsachik Gelander, Alexander Lubotzky, and Aner Shalev SECOND SERIES, VOL. 172, NO. 3 November, 2010 anmaah Annals of Mathematics, 172 (2010), 2197–2221 Counting arithmetic lattices and surfaces By MIKHAIL BELOLIPETSKY, TSACHIK GELANDER, ALEXANDER LUBOTZKY, and ANER SHALEV Abstract We give estimates on the number ALH .x/ of conjugacy classes of arithmetic lattices of covolume at most x in a simple Lie group H . In particular, we obtain a first concrete estimate on the number of arithmetic 3-manifolds of volume at most x. Our main result is for the classical case H PSL.2; R/ where we show D that log AL .x/ 1 lim H : x x log x D 2 !1 The proofs use several different techniques: geometric (bounding the number of generators of as a function of its covolume), number theoretic (bounding the number of maximal such ) and sharp estimates on the character values of the symmetric groups (to bound the subgroup growth of ). 1. Introduction Let H be a noncompact simple Lie group with a fixed Haar measure .A discrete subgroup of H is called a lattice if . H / < . A classical theorem of n 1 Wang[Wan72] asserts that if H is not locally isomorphic to PSL2.R/ or PSL2.C/, then for every 0 < x R the number LH .x/ of conjugacy classes of lattices in H of 2 covolume at most x is finite. This result was greatly extended by Borel and Prasad [BP89]. In recent years there has been an attempt to quantify Wang’s theorem and to give some estimates on LH .x/ (see[BGLM02],[Gel04],[GLNP04],[Bel07] and[BL]). -

IMU Secretary An: [email protected]; CC: Betreff: IMU EC CL 05/07: Vote on ICMI Terms of Reference Change Datum: Mittwoch, 24

Appendix 10.1.1 Von: IMU Secretary An: [email protected]; CC: Betreff: IMU EC CL 05/07: vote on ICMI terms of reference change Datum: Mittwoch, 24. Januar 2007 11:42:40 Anlagen: To the IMU 2007-2010 Executive Committee Dear colleagues, We are currently experimenting with a groupware system that may help us organize the files that every EC member should know and improve the voting processes. Wolfgang Dalitz has checked the open source groupware systems and selected one that we want to try. It is more complicated than we thought and does have some deficiencies, but we see no freeware that is better. Here is our test run with a vote on a change of the ICMI terms of reference. To get to our voting system click on http://www.mathunion.org/ec-only/ To log in, you have to type your last name in the following version: ball, baouendi, deleon, groetschel, lovasz, ma, piene, procesi, vassiliev, viana Right now, everybody has the same password: pw123 You will immediately get to the summary page which contains an item "New Polls". The question to vote on is: Vote-070124: Change of ICMI terms of reference, #3, see Files->Voting->Vote- 070124 for full information and you are supposed to agree, disagree or abstain by clicking on the corresponding button. Full information about the contents of the vote is documented in the directory Voting (click on the +) where you will find a file Vote-070124.txt (click on the "txt icon" to see the contents of the file). The file is also enclosed below for your information. -

Ergodic Theory Plays a Key Role in Multiple Fields Steven Ashley Science Writer

CORE CONCEPTS Core Concept: Ergodic theory plays a key role in multiple fields Steven Ashley Science Writer Statistical mechanics is a powerful set of professor Tom Ward, reached a key milestone mathematical tools that uses probability the- in the early 1930s when American mathema- ory to bridge the enormous gap between the tician George D. Birkhoff and Austrian-Hun- unknowable behaviors of individual atoms garian (and later, American) mathematician and molecules and those of large aggregate sys- and physicist John von Neumann separately tems of them—a volume of gas, for example. reconsidered and reformulated Boltzmann’ser- Fundamental to statistical mechanics is godic hypothesis, leading to the pointwise and ergodic theory, which offers a mathematical mean ergodic theories, respectively (see ref. 1). means to study the long-term average behavior These results consider a dynamical sys- of complex systems, such as the behavior of tem—whetheranidealgasorothercomplex molecules in a gas or the interactions of vi- systems—in which some transformation func- brating atoms in a crystal. The landmark con- tion maps the phase state of the system into cepts and methods of ergodic theory continue its state one unit of time later. “Given a mea- to play an important role in statistical mechan- sure-preserving system, a probability space ics, physics, mathematics, and other fields. that is acted on by the transformation in Ergodicity was first introduced by the a way that models physical conservation laws, Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann laid Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann in the what properties might it have?” asks Ward, 1870s, following on the originator of statisti- who is managing editor of the journal Ergodic the foundation for modern-day ergodic the- cal mechanics, physicist James Clark Max- Theory and Dynamical Systems.Themeasure ory. -

Prospects in Topology

Annals of Mathematics Studies Number 138 Prospects in Topology PROCEEDINGS OF A CONFERENCE IN HONOR OF WILLIAM BROWDER edited by Frank Quinn PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1995 Copyright © 1995 by Princeton University Press ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Annals of Mathematics Studies are edited by Luis A. Caffarelli, John N. Mather, and Elias M. Stein Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources Printed in the United States of America by Princeton Academic Press 10 987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prospects in topology : proceedings of a conference in honor of W illiam Browder / Edited by Frank Quinn. p. cm. — (Annals of mathematics studies ; no. 138) Conference held Mar. 1994, at Princeton University. Includes bibliographical references. ISB N 0-691-02729-3 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-691-02728-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Topology— Congresses. I. Browder, William. II. Quinn, F. (Frank), 1946- . III. Series. QA611.A1P76 1996 514— dc20 95-25751 The publisher would like to acknowledge the editor of this volume for providing the camera-ready copy from which this book was printed PROSPECTS IN TOPOLOGY F r a n k Q u in n , E d it o r Proceedings of a conference in honor of William Browder Princeton, March 1994 Contents Foreword..........................................................................................................vii Program of the conference ................................................................................ix Mathematical descendants of William Browder...............................................xi A. Adem and R. J. Milgram, The mod 2 cohomology rings of rank 3 simple groups are Cohen-Macaulay........................................................................3 A. -

All That Math Portraits of Mathematicians As Young Researchers

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 06, 2021 All that Math Portraits of mathematicians as young researchers Hansen, Vagn Lundsgaard Published in: EMS Newsletter Publication date: 2012 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Hansen, V. L. (2012). All that Math: Portraits of mathematicians as young researchers. EMS Newsletter, (85), 61-62. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. NEWSLETTER OF THE EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Editorial Obituary Feature Interview 6ecm Marco Brunella Alan Turing’s Centenary Endre Szemerédi p. 4 p. 29 p. 32 p. 39 September 2012 Issue 85 ISSN 1027-488X S E European M M Mathematical E S Society Applied Mathematics Journals from Cambridge journals.cambridge.org/pem journals.cambridge.org/ejm journals.cambridge.org/psp journals.cambridge.org/flm journals.cambridge.org/anz journals.cambridge.org/pes journals.cambridge.org/prm journals.cambridge.org/anu journals.cambridge.org/mtk Receive a free trial to the latest issue of each of our mathematics journals at journals.cambridge.org/maths Cambridge Press Applied Maths Advert_AW.indd 1 30/07/2012 12:11 Contents Editorial Team Editors-in-Chief Jorge Buescu (2009–2012) European (Book Reviews) Vicente Muñoz (2005–2012) Dep. -

On Some Recent Developments in the Theory of Buildings

On some recent developments in the theory of buildings Bertrand REMY∗ Abstract. Buildings are cell complexes with so remarkable symmetry properties that many groups from important families act on them. We present some examples of results in Lie theory and geometric group theory obtained thanks to these highly transitive actions. The chosen examples are related to classical and less classical (often non-linear) group-theoretic situations. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010). 51E24, 20E42, 20E32, 20F65, 22E65, 14G22, 20F20. Keywords. Algebraic, discrete, profinite group, rigidity, linearity, simplicity, building, Bruhat-Tits' theory, Kac-Moody theory. Introduction Buildings are cell complexes with distinguished subcomplexes, called apartments, requested to satisfy strong incidence properties. The notion was invented by J. Tits about 50 years ago and quickly became useful in many group-theoretic situations [75]. By their very definition, buildings are expected to have many symmetries, and this is indeed the case quite often. Buildings are relevant to Lie theory since the geometry of apartments is described by means of Coxeter groups: apartments are so to speak generalized tilings, where a usual (spherical, Euclidean or hyper- bolic) reflection group may be replaced by a more general Coxeter group. One consequence of the existence of sufficiently large automorphism groups is the fact that many buildings admit group actions with very strong transitivity properties, leading to a better understanding of the groups under consideration. The beginning of the development of the theory is closely related to the theory of algebraic groups, more precisely to Borel-Tits' theory of isotropic reductive groups over arbitrary fields and to Bruhat-Tits' theory of reductive groups over non-archimedean valued fields. -

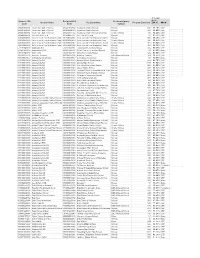

CEP May 1 Notification for USDA

40% and Sponsor LEA Recipient LEA Recipient Agency above Sponsor Name Recipient Name Program Enroll Cnt ISP % PROV Code Code Subtype 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280201860934 Academy Charter School School 435 61.15% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 800000084303 Academy Charter School School 605 61.65% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280202861142 Academy Charter School-Uniondale Charter School 180 72.22% CEP 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed School 91 90.11% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 331300860902 Achievement First Endeavor Charter School 805 54.16% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 800000086469 Achievement First University Prep Charter School 380 54.21% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 332300860912 Achievement First Brownsville Charte Charter School 801 60.92% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charter School 393 62.34% CEP 570101040000 Addison CSD 570101040001 Tuscarora Elementary School School 455 46.37% CEP 410401060000 Adirondack CSD 410401060002 West Leyden Elementary School School 139 40.29% None 080101040000 Afton CSD 080101040002 Afton Elementary School School 545 41.65% CEP 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva BJE Affiliated School 169 71.01% CEP 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya School 140 68.57% None 010100010000 Albany City SD 010100010023 Albany School Of Humanities School 554 46.75% CEP 010100010000 Albany -

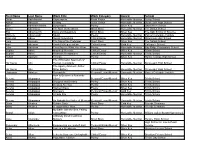

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School

First Name Last Name Work Title Work Category Award School Omar Abdelhamid Skyscrapers Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Trinity School Adrian Aboyoun Driving Flash Fiction Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Edie Abraham-Macht Suspended Poetry Silver Key Saint Ann's School Grace Abrahams The Man on the Street Short Story Honorable Mention The Dalton School Etai Abramovich Sons and Daughters Short Story Silver Key The Salk School of Science Michelle Abramowitz Squid Poetry Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute Diamond Abreu Social Networking Critical Essay Honorable Mention Millennium High School Lucy Ackman The Day of the Professor Short Story Silver Key The Dalton School max adelman Hamlet's Regeneration Critical Essay Gold Key Collegiate School Lebe Adelman They Say It’s What You Wear Poetry Honorable Mention Bay Ridge Preparatory School Sophia Africk Morphed Mercutio Critical Essay Silver Key Trinity School Sophia Africk Richard's Realizations Critical Essay Honorable Mention Trinity School Rohan Agarwal Friends Poetry Silver Key Hunter College High School The Whitmanic Spectrum of Ha Young Ahn Human Immortality Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School The Agency Moment: Arthur Ha Young Ahn Miller Edition Critical Essay Honorable Mention Stuyvesant High School Hadassah Akinleye Second Air Personal Essay/Memoir Honorable Mention Packer Collegiate Institute How to Become a Romantic Serena Alagappan Cliché Personal Essay/Memoir Silver Key Trinity School Serena Alagappan Drugged and Dreamy Poetry Silver Key Trinity