Slavery in Dutch Colombo a Social History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs CoMTrans UrbanTransport Master Plan Final Report CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1.1 Definition The Western Province is the most developed province in Sri Lanka and is where the administrative functions and economic activities are concentrated. At the same time, forestry and agricultural lands still remain, mainly in the eastern and south-eastern parts of the province. And also, there are some local urban centres which are less dependent on Colombo. These areas have less relation with the centre of Colombo. The Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined in order to analyse and assess future transport demands and formulate a master plan. For this purpose, Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined by: A) areas that are already urbanised and those to be urbanised by 2035, and B) areas that are dependent on Colombo. In an urbanised area, urban activities, which are mainly commercial and business activities, are active and it is assumed that demand for transport is high. People living in areas dependent on Colombo area assumed to travel to Colombo by some transport measures. 4.1.2 Factors to Consider for Future Urban Structures In order to identify the CMA, the following factors are considered. These factors will also define the urban structure, which is described in Section 4.3. An effective transport network will be proposed based on the urban structure as well as the traffic demand. At the same time, the new transport network proposed will affect the urban structure and lead to urban development. -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

Available Geo-Spatial Data at GIS & Mapping Section

Available geo-spatial data at GIS & Mapping Section GIS & MAPPING SECTION NATIONAL WAER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE BOARD VERSION 1.0 16/12/2015 Introduction The main objective of GIS & Mapping Section of NWS&DB is to serve as the main agency in surveying, mapping and in geo-spatial activities and having a particular responsibility within the organization. A few major contributions from this section are surveys and mapping of water distribution network, digitization of as-built drawings and analogue drawings using latest techniques, upgrading same to a higher level of accuracy and also taking initiatives towards building up of Geographic Information System (GIS) and Spatial Data Infrastructure( SDI)for NWS&DB. This manual provides details regarding available Geo-Spatial Data at GIS & Mapping Section. First part of this manual contains information about available maps of Water, Sewer and Storm utilities. It also describes availability ofrelevant Base-maps. Second part of this manual describes availability of Base-maps obtained from the Survey Department of Sri Lanka. We have also included details of Base-maps (prepared for SIIRM Project)obtained from the Urban Development Authority ( UDA ) and some Base-maps prepared by GIS & Mapping Section itself. Final part of this manual contains availability of Sri Lanka maps collected from different sources and processed by GIS & Mapping Section which carries different thematic details including Sri Lanka Administration Boundary Maps classified under deferent categories. Contact Details: GIS & Mapping Section National Water Supply & Drainage Board Thelawala Road Rathmalana Tel : +94 11 2636770 Fax : +94 11 2624727 E-mail : [email protected] 1 Content 1. Utility Data 1.1. -

Country of Origin Information Report Sri Lanka March 2008

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SRI LANKA 3 MARCH 2008 Border & Immigration Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 3 MARCH 2008 SRI LANKA Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA, FROM 1 FEBRUARY TO 27 FEBRUARY 2008 REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 1 FEBRUARY AND 27 FEBRUARY 2008 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY........................................................................................ 1.01 Map ................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY............................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY.............................................................................................. 3.01 The Internal conflict and the peace process.............................. 3.13 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS...................................................................... 4.01 Useful sources for updates ......................................................... 4.18 5. CONSTITUTION..................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .............................................................................. 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 7.01 8. SECURITY FORCES............................................................................... 8.01 Police............................................................................................ -

Ayubowan Welcome to Sri Lanka!

SRI LANKA DESTINATION INFORMATION AYUBOWAN WELCOME TO SRI LANKA! Sri Lanka is a diverse destination with an amazing range of experiences for a relatively small island. The recorded history of the island dates back 2,500 years, when an exiled prince from northern India drifted onto the shores of Sri Lanka to establish the first known civilization here. It boasts a varied range of landscapes from golden beaches to rolling hills, forests and lush tea plantations. Sri Lanka was formerly known as “Serendib”, which means ‘wondrous surprise’ – and indeed it is! A beautiful island, the country was once referred to as “the fairest isle” by Marco Polo. Geographically, Sri Lanka lies like a teardrop in the Indian Ocean off the southeast coast of India. The country has a 90% literacy rate and a very friendly local population, which has enhanced its popularity as a tourist destination. GEOGRAPHY FAST FACT Sri Lanka is a southern Asian island country in the Indian Ocean, situated between the Laccadive Sea and the Bay of Bengal. It is located 31 OFFICIAL NAME km off the southeastern coast of India, and features diverse landscapes Democratic Socialist Republic of that range from rainforest and arid plains to highlands and sandy beaches. Sri Lanka Away from the pristine coastline in the center of the island is “The Cultural Triangle”. This region comprises a succession of ancient capitals CAPITAL CITY and Buddhist sites where intricate carvings and towering stone monuments Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte are scattered throughout the forests. (a suburb of the commercial Huge man-made lakes (water tanks) have kept the central area irrigated capital and largest city, Colombo) for millennia and continue to provide water for paddy fields and thirsty elephants that regularly leave the shelter of the jungle to come and drink. -

Housing Units by Type of Unit and GN Division 2012.Xlsx

Census of Population and Housing ‐ 2012 Housing units by type of unit and District/ DS Division/ GN Division. Type of Unit District/DS/GN Division GN No. Total Permanent Semi‐permanent Improvised Un‐classified Sri Lanka 5,207,740 4,238,491 927,408 40,464 1,377 Colombo 562,550 526,635 34,452 1,227 236 Colombo 65,831 60,512 5,157 121 41 Sammanthranapura 1,687 1,175 493 19 ‐ Mattakkuliya 6,143 5,580 562 1 ‐ Modara 3,874 3,679 192 3 ‐ Madampitiya 2,821 1,794 1,013 14 ‐ Mahawatta 1,866 1,638 226 2 ‐ Aluthmawatha 3,164 2,902 257 5 ‐ Lunupokuna 2,777 2,605 169 3 ‐ Bloemendhal 3,199 2,575 610 14 ‐ Kotahena East 1,567 1,557 10 ‐ ‐ Kotahena West 2,113 2,085 28 ‐ ‐ Kochchikade North 1,858 1,846 12 ‐ ‐ Jinthupitiya 1,666 1,639 27 ‐ ‐ Masangasweediya 1,532 1,501 31 ‐ ‐ New Bazaar 2,501 2,465 28 8 ‐ Grandpass South 3,699 3,521 163 15 ‐ Grandpass North 1,659 1,603 46 2 8 Nawagampura 1,442 1,253 182 1 6 Maligawatta East 2,266 2,084 155 ‐ 27 Khettarama 2,647 2,182 438 27 ‐ Aluthkade East 1,676 1,666 10 ‐ ‐ Aluthkade West 1,275 1,262 13 ‐ ‐ Kochchikade South 1,442 1,434 8 ‐ ‐ Pettah 34 34 ‐ ‐ ‐ Fort 130 130 ‐ ‐ ‐ Galle Face 723 708 15 ‐ ‐ Slave Island 715 710 5 ‐ ‐ Hunupitiya 1,358 1,218 139 1 ‐ Suduwella 783 748 30 5 ‐ Keselwatta 1,387 1,328 59 ‐ ‐ Panchikawatta 1,709 1,653 55 1 ‐ Maligawatta West 1,894 1,851 43 ‐ ‐ Maligakanda 1,501 1,449 52 ‐ ‐ Maradana 910 884 26 ‐ ‐ Ibbanwala 470 461 9 ‐ ‐ Wekanda 1,343 1,292 51 ‐ ‐ Kolonnawa 44,663 39,977 4,304 341 41 Wadulla 509D 1,750 1,213 523 14 ‐ Sedawatta 509A 1,567 1,168 386 13 ‐ Halmulla 509C 535 452 74 9 -

Catalogue of the Archives of the Dutch Central Government of Coastal Ceylon, 1640-1796

Catalogue of the Archives of the Dutch Central Government of Coastal Ceylon, 1640-1796 M.W. Jurriaanse Department of National Archives of Sri Lanka, Colombo ©1943 This inventory is written in English. 3 CONTENTS FONDS SPECIFICATIONS CONTEXT AND STRUCTURE .................................................... 13 Context ................................................................................................................. 15 Biographical History .......................................................................................... 15 The establishment of Dutch power in Ceylon .................................................. 15 The development of the administration. .......................................................... 18 The Governor. ......................................................................................... 22 The Council. ............................................................................................ 23 The "Hoofdadministrateur" and officers connected with his department. ....... 25 The Colombo Dessave. ............................................................................. 26 The Secretary. ......................................................................................... 28 The history of the archives. ................................................................................. 29 Context and Structure .......................................................................................... 37 The catalogue. .................................................................................................. -

^ARCHITECTURE O/An IS LAND

^ARCHITECTURE o/an IS LAND The Living Heritage Of Sri Lanka RONALD LEWCOCK BARBARA SANSONI LAKI SENANAYAKE Contents Foreword PAGE XIII Acknowledgements XIV Location Map XVI Introduction The Making of this Book I Sinhalese Vernacular Domestic Buildings A Introduction and Primitive Village Forms 1 Cadjan Buildings 3 2 A Brick Kiln, Hanwella 6 3 A Hen Coop 7 4 A Farm House, Kalundewa, Dambulla 9 5 The Sinhalese Village of Mahakirinda, Kurunegala 1 2 6 A House, Paddukulama, Anuradhapura B Courtyard Forms 19 7 A House, Medamahanuwara 23 8 A House, Medawela, near Kandy 24 9 A House, Menikdiwela, Kadugannawa 27 10 Unduruwa Walauwe, Ranawa, Dambulla 31 11 The Mahagedera, Ukuwela, Matale 33 12 Kalugalle Walauwe, Nugawela 36 13 Parana Walauwe, Ukuwela, Matale 38 14 Maduanwala Walauwe, Ratnapura 40 II Buddhist Monks' Houses 42 15 The Monks' House and Poya Ge, Gadaladeniya 44 Contents • THE ARCHITECTURE OF AN ISLAND VII 16 The Monks', House and Rice Bins, Lankatilleke 46 17 The Monks' House and Popa Ge, Degaldoruwa 48 18 The Monks' House, Dalukgolle, Kandy $o III Hindu Vernacular Domestic Buildings ... $3 19 A High Caste Hindu House, Jaffna 56 20 A Chetty House, Jaffna 62 IV Moslem Vernacular Domestic Buildings 67 21 A Seventeenth Century Trader's House, Galle Fort 68 V Sinhalese Secular Vernacular Buildings 71 22 Panavitiya Ambalama, Kurunegala 72 23 The Ambalama, Kadugannawa 74 24 Bogoda Bridge, Badulla 76 VI Hindu Secular Vernacular Buildings 81 25 Kumbiyangoda Ambalama, Matale 82 VII Buddhist Temples 85 26 Kande Vihare, Kadugannawa 89 2 7 Dowe -

OCR Document

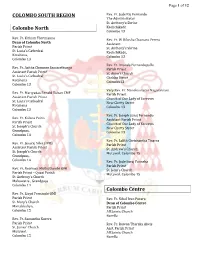

Page 1 of 12 COLOMBO SOUTH REGION Rev. Fr. Jude Raj Fernando The Administrator St. Anthony's Shrine Colombo North Kochchikade Colombo 13 Rev. Fr. Kithsiri Thirimanne Rev. Fr. W Dilusha Chamara Perera Dean of Colombo North Assistant Parish Priest St. Anthony's Shrine St. Lucia's Cathedral Kochchikade, Kotahena, Colombo 13 Colombo 13 Rev. Fr. Ananda Fernandopulle Rev. Fr. Asitha Chamara Samarathunga Parish Priest Assistant Parish Priest St. Anne's Church St. Lucia's Cathedral Chekku Street Kotahena Colombo13 Colombo 13 Very Rev. Fr. Manokumaran Nagaratnam Rev. Fr. Mariyadas Renald Ruban CMF Parish Priest Assistant Parish Priest Church of Our Lady of Sorrows St. Lucia's Cathedral New Chetty Street Kotahena Colombo 13 Colombo 13 Rev. Fr. Joseph Suraj Fernando Rev. Fr. Kalana Peiris Assistant Parish Priest Parish Priest Church of Our Lady of Sorrows St. Joseph's Church New Chetty Street Grandpass, Colombo 13 Colombo 14 Rev. Fr. Lalith Chrishantha Tissera Rev. Fr. Jesuraj Silva (IVD) Parish Priest Assistant Parish Priest St. Andrew's Church St. Joseph's Church Mutuwal, Colombo 15 Grandpass, Colombo 14 Rev. Fr. Jude Suraj Fonseka Parish Priest Rev. Fr. Newman Muthuthambi OMI St. John's Church Parish Priest – Quasi Parish Mutuwal, Colombo 15 St. Anthony’s Church Mahawatte , Grandpass Colombo 14 Colombo Centre Rev. Fr. Lloyd Fernando OMI Parish Priest Rev. Fr. Nihal Ivan Perera St. Mary's Church Dean of Colombo Centre Mattakkuliya, Parish Priest Colombo 15 All Saints Church Borella Rev. Fr. Samantha Kurera Parish Priest Rev. Fr. Ruwan Tharaka Alwis St. James' Church Asst. Parish Priest Mutuwal, All Saints Church Colombo 15 Borella Page 2 of 12 Rev. -

The Beira Lake Intervention Area Development Plan

BEIRA LAKE DEVELOPMENT – PLANNING HISTORY Sri Lanka and Canadian Professionals were prepared Master Plan for Beira Lake and surrounding areas based on the Beira Lake Restoration Study, 1993. It was a comprehensive study and identified 15 sites to turn Colombo into water–front city using the Beira Lake as a central attraction an existing open area. BEIRA LAKE DEVELOPMENT – PLANNING HISTORY The lands released for development under this plan, • Lands along the Baladaksha Mawatha, (Army Head Quarters land) • Colombo Commercial Land at Sir James Peris Mawatha, • Slave Island redevelopment stage I & II. The Linear Park development along the South Beira Lake was completed by the UDA in 2001/2005. BEIRA LAKE DEVELOPMENT – PLANNING HISTORY The Master Plan consists with three sub plans. 1. Environmental improvement plan It has been proposed to resettle the underserved settlements around the lake. The plan has proposed to make more green access roads to the Lake, those are connected with the linear park which will be constructed around the lake for the public use. The plan further proposes to establish nodal parks for the public use as well as improve the natural environment of the area. 2. Water management plan Water Management Plan considers to improve the water quality of the lake for open up the lake for recreational activities. Under that, proposed to redirect all the illegal sewer and waste water connections at the catchment connect them to central waste water system of the Colombo Municipal Council. 3. Business plan Number of state and privately owned lands which are being used for sub optimal uses have been identified by the master plan for redevelopment. -

URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN Urban Transport Development Programmes Development for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

Objectives for Urban Transport Policy Urban Transport System URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN Urban Transport Development Programmes Development For Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka The analysis of the present To achieve the four different The various policy measures proposed Ministry of Transport urban transport problems and objectives for transport system to achieve the urban transport policies the planning issues in the CMA development, the following and major projects of CoMTrans Urban Japan International Cooperation Agency has led to the identiication transport policies are essential for Transport Master Plan are listed below; of four major objectives which the CMA. These four transport Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. the urban transport system policies are interrelated. Extensive Development of Quality of Public development needs to pursue. The promotion of public transport is a Transport Network principal measure to reduce dependence Enhancement of Intermodality (Development on private modes of transport. of Multimodal Transport Hub, Multi Modal Urban Transport Problems and Planning Issues in Colombo Metropolitan Area Centre and Park and Ride Facility) Modernisation of Sri Lanka Railway Main Line, Colombo is the most developed city in the Western Province of Sri Lanka. Coast Line and Puttam Line (Electriication, Colombo Metropolitan Area (CMA) is set around Colombo and deined by: Direct Operation, Improvement of 1) areas that are already urbanised and those to be urbanised by 2035, -

Another Disaster?

GroundView Free first issue Price Rs 15.00 Volume 1 No. 1 January 2007 INSIDE Response to floods and landslides: voices from the regions Stopping the slide Page 5 Rising from the ashes Page 7 Cry Vaharai: on the run again Page 8 Are we prepared for Sweep stakes Pic by K.D. Dewapriya for survival Page 9 ANOTHER DISASTER? Puttalam By Prasad Poornamal We don’t want ‘buth packets.’ Jayamanna, Puttalam Settling where Building risk based planning into develop- S Sheela (33): “When Colombo Due to incessant rains which gets affected, roads and canals are displaced lasted a month, several reser- ment decisions and durable, resistant infra- fixed fast, because the ‘loku maha- voirs in the Udaha area in Put- structure are the needs of the hour and not thuru’ and ‘amithigollo’ (politicians Page 10 talam district overflowed, flood- and influential individuals) are there. ing a large area. The problem simply the allocations of millions of rupees Even with deaths and starvation no was aggravated by the fact that for relief activities after a disaster strikes. one hears our plight.Another flood flood waters from Kurunegala, will come and go with nothing being Shanty Kuliyapitiya, and Galgamuwa Puttalam District Secretary. Deduru Oya, Mee Oya and done.” had also entered the district en The most recent floods had- Lunu Oya were among the D A Mangala Priyantha (35): “The subculture route to the sea. displaced 16,000 families, fully reservoirs which overflowed. canal is yet to be repaired. We have Floods, which occurred on destroyed 250 houses, and par- The worst affected areas in the informed all the responsible author- Page 11 four occasions, had rendered tially damaged 10,000.