Cultivating Protective Environments: Suicide and the Need for Interdisciplinary Health Equity Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights Research Team: Juliana Martínez, PhD; Ángela Duarte, MA; María Juliana Rojas, EdM and MA. Sentiido (Colombia) March 2021 The Elevate Children Funders Group is the leading global network of funders focused exclusively on the wellbeing and rights of children and youth. We focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence. Global Philanthropy Project (GPP) is a collaboration of funders and philanthropic advisors working to expand global philanthropic support to advance the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people in the Global1 South and East. TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ...................................................................................... 4 Acronyms .................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the Directors: ......................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................... 10 Report Outline ..........................................................................................13 MOBILIZING A GENDER-RESTRICTIVE WORLDVIEW .... 14 The Making of the Contemporary Gender-Restrictive Movement ................................................... 18 Instrumentalizing Cultural Anxieties ......................................... -

The Trevor Project's Strategic Plan 2020–2023

MEETING THE CALL The Trevor Project’s Strategic Plan 2020–2023 2 Leadership perspective LEADERSHIP PERSPECTIVE The Trevor Project was founded more than two decades ago to respond to a public health crisis impacting LGBTQ youth — a crisis whose magnitude is huge, and one that we have worked tirelessly to end. LGBTQ young people are more than four times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers, and suicide remains the second leading cause of death among all young people in the United States. In 2019, our research team published the nation’s first estimate of LGBTQ youth considering suicide in partnership with leading experts from across the country. This ground-breaking research showed that over 1.8 million LGBTQ young people in the United States consider suicide each year. Thanks to the work of our team, our volunteers, and our supporters across the country, The Trevor Project has become the leading global organization responding to the crisis of LGBTQ youth suicide. We have grown from a 24/7 phone Lifeline reaching several thousand youth per year, to a preeminent resource for LGBTQ youth in crisis — one that remains the primary resource for over half of the youth who reach out to us. While continuing to grow the impact of our Lifeline substantially, we have also launched on-demand digital services for youth to reach out 24/7 over text and online. In addition, we created TrevorSpace, the largest safe space social network for LGBTQ youth to connect — not just in the United States, but in over 100 countries across the globe. -

Health 2020 Youth National on Survey

NATIONAL SURVEY ON LGBTQ YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH 2020 INTRODUCTION Experts are just beginning to understand Among some of the key findings of the report This year’s survey exemplifies our the mental health impacts of the multiple from LGBTQ youth in the survey: organization’s commitment to using crises in 2020 that have deeply impacted • 40% of LGBTQ respondents seriously research and data to prevent LGBTQ youth so many. But we know that suicide is still a suicide. public health crisis, consistently the second considered attempting suicide in the past twelve months, with more than half of leading cause of death among young people, We will continue to leverage new research and continues to disproportionately impact transgender and nonbinary youth having seriously considered suicide to help inform our life-saving services for LGBTQ youth. The need for robust research, LGBTQ youth, as well as expand the • 68% of LGBTQ youth systematic data collection, and comprehen- reported knowledge base for organizations around sive mental health support has never been symptoms of generalized anxiety dis- the globe. Our partner organizations also greater. order in the past two weeks, including conduct critical research, and we more than 3 in 4 transgender and nonbi- acknowledge that our life-saving programs The Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey nary youth and research build on their important work. on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health is our • 48% of LGBTQ youth reported engaging second annual release of new insights in self-harm in the past twelve months, Given the lack of LGBTQ-inclusive data into the unique challenges that LGBTQ including over 60% of transgender and nationwide, we hope this report will provide youth face every day. -

Trevor Project National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health

NATIONAL SURVEY ON LGBTQ YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH 2019 INTRODUCTION I’m proud to share The Trevor Project’s inaugural National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. This is our first wide-ranging report from Among some of the key findings of the The Trevor Project’s a cross-sectional national survey of LGBTQ report from LGBTQ youth in the survey: youth across the United States. With National Survey on LGBTQ Youth over 34,000 respondents, it is the largest • 39% of LGBTQ youth seriously Mental Health is part of our considered attempting suicide in the survey of LGBTQ youth mental health commitment to use research and ever conducted and provides a critical past twelve months, with more understanding of the experiences than half of transgender and non-binary data to continually improve impacting their lives. youth having seriously considered our life-saving services for LGBTQ • 71% of LGBTQ youth reported youth and expand the know- This ground-breaking survey feeling sad or hopeless for at least provides new insights into two weeks in the past year ledge base for organizations the challenges that LGBTQ youth • Less than half of LGBTQ respondents around the globe. across the country face every were out to an adult at school, with youth less likely to disclose their This survey builds upon critical research day, including suicide, feeling sad gender identity than sexual orientation done by many of our partner organizations over the years and we are particularly or hopeless, discrimination, • 2 in 3 LGBTQ youth reported that proud that it is inclusive of youth of more physical threats and exposure someone tried to convince them than 100 sexual orientations and to conversion therapy. -

The City of New York Office of the Mayor New York, Ny 10007

THE CITY OF NEW YORK OFFICE OF THE MAYOR NEW YORK, NY 10007 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: March 29, 2020, 4:15 PM CONTACT: [email protected], (212) 788-2958 TRANSCRIPT: MAYOR DE BLASIO HOLDS MEDIA AVAILABILITY ON COVID-19 Mayor Bill de Blasio: Good afternoon, everyone. We've got a lot to go over here and we're all feeling very heavy hearts as we deal with such an extraordinary challenge and we think about the New Yorkers that we've lost and we think about what's ahead and I'm going to go over a number of things now that update you. Understanding the challenge but also understanding that New Yorkers will get through this together and it’s hard to explain that balance sometimes that we're dealing with something absolutely profoundly different than anything we've dealt with before, extraordinarily difficult and invisible and confusing, but we will get through this together. That is something that comes back to just the pure strength of this place and our people. But in the meantime, we will go through a really tough, tough journey and it all comes back to, as always, needing to work with the federal government in particular to get the help we need. And I'll give you some updates starting there. There was confusion yesterday obviously when President Trump mentioned the concept of quarantine. I think a lot of us were confused, thought it was something that would be in so many ways counterproductive and obviously unfair to so many people. What ended up happening was a CDC travel advisory, something much different – not a lockdown, something much more consistent with what we've been actually saying and doing in the city and state already, which is telling people to stay home unless they have an essential reason to go somewhere. -

MODEL SCHOOL DISTRICT POLICY on SUICIDE PREVENTION Model Language, Commentary, and Resources

MODEL SCHOOL DISTRICT POLICY ON SUICIDE PREVENTION Model Language, Commentary, and Resources The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) is the leading national not-for-profit organization exclusively dedicated to understanding and preventing TABLE OF CONTENTS suicide through research, education and advocacy, and to reaching out to people with mental disorders and those impacted by suicide. To fully achieve its mission, Introduction ..................................................................... 1 AFSP engages in the following Five Core Strategies: Purpose ............................................................................ 1 1) fund scientific research, 2) offer educational programs Parental Involvement ....................................................... 1 for professionals, 3) educate the public about mood disorders and suicide prevention, 4) promote policies Definitions ......................................................................... 2 and legislation that impact suicide and prevention, and 5) provide programs and resources for survivors of Scope ................................................................................ 3 suicide loss and people at risk, and involve them in the Importance of School-based work of the Foundation. Learn more at www.afsp.org. Mental Health Supports ................................................... 3 Risk Factors and Protective Factors .................................. 3 The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) promotes student success by expanding the -

Evidence on Covid-19 Suicide Risk and LGBTQ Youth

The Trevor Project Research Brief: Evidence on Covid-19 Suicide Risk and LGBTQ Youth January 2021 Summary The Covid-19 pandemic has upended the lives of people around the world, with detrimental impacts on not only physical health but also mental health. Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, concerns have arisen around potential increases in suicide risk, particularly among marginalized populations. Prior to the pandemic, LGBTQ youth have been found to be at significantly greater risk for seriously considering and attempting suicide (Johns et al., 2019; Johns et al., 2020). More research will continue to be conducted, but it is important that current conversations around Covid-19 and suicide risk be evidence-based and data-informed. This brief reviews existing research and data on the association between the Covid-19 pandemic and suicide risk, including as it relates to risk among LGBTQ youth. Results Deaths by suicide in the U.S. since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic It is still too early to know the full effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on suicide rates. Within the U.S., national suicide death data for 2020 is not yet available (Kochanek et al., 2020). However, in order for suicide deaths to outpace deaths from Covid-19, they would need to occur at seven times the recent annual rate of nearly 50,000 to match the more than 350,000 deaths from Covid-19. Trends data from Massachusetts and Austin, Texas indicate no change and decreases, respectively in suicide deaths (Austin Police Department, 2020; Faust et al., 2020). -

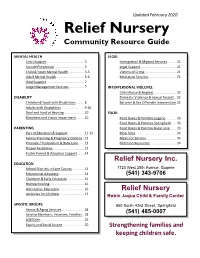

Community Resource Guide

Updated February 2020 Relief Nursery Community Resource Guide MENTAL HEALTH LEGAL Crisis Support ...................................... 3 Immigration & Migrant Services ......... 21 Suicide Prevention .............................. 3 Legal Support .................................... 21 Child & Youth Mental Health ............... 3-5 Victims of Crime ................................ 21 Adult Mental Health ............................ 5-6 Mediation Services ............................ 21 Grief Support ...................................... 7 Anger Management Services ............... 7 INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE Child Abuse & Neglect ....................... 22 DISABILITY Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault .. 22 Children & Youth with Disabilities ........ 8 Batterer & Sex Offender Intervention 22 Adults with Disabilities ...................... 9-10 Deaf and Hard of Hearing .................... 10 FOOD Blindness and Vision Impairment ........ 10 Food Boxes & Pantries Eugene .......... 23 Food Boxes & Pantries Springfield ..... 23 PARENTING Food Boxes & Pantries Rural Lane ...... 23 Parent Education & Support ................ 11-12 Meal Sites ......................................... 24 Family Planning & Pregnancy Options . 12 Meals for Seniors............................... 24 Prenatal / Postpartum & Baby Care...... 13 Nutrition Resources .......................... 24 Diaper Assistance................................ 13 Foster Parent & Adoption Support....... 14 Relief Nursery Inc. EDUCATION School Districts in Lane County ............ 14 1720 -

Class Action Lawsuit

Case 1:18-cv-06109 Document 1 Filed 11/01/18 Page 1 of 47 PageID #: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK M.F., a minor, by and through his parent and natural guardian YELENA FERRER; M.R., a minor, by and through her parent and natural No. 18-CV-6109 guardian JOCELYNE ROJAS; I.F., a minor, by and through her parent and natural guardian COMPLAINT JENNIFER FOX, on behalf of themselves and a class of those similarly situated; and THE AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION, a nonprofit organization, Plaintiffs, -against- THE NEW YOR K CITY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION; THE NEW YOR K CITY DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND MENTAL HYGIENE; THE OFFICE OF SCHOOL HEALTH; THE CITY OF NEW YORK; BILL DE BLASIO, in his official capacity as Mayor of New York City; RICHARD A. CARRANZA, in his official capacity as Chancellor of the New York City Department of Education; OXIRIS BARBOT, in her official capacity as Acting Commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; and ROGER PLATT, in his official capacity as Chief Executive Officer of the Office of School Health, Defendants. INTRODUCTION 1. This class action lawsuit challenges the New York City Department of Education’s and the above-named Defendants’ (collectively, “DOE” or “Defendants”) ongoing and systemic failure to provide appropriate care to students with type 1 diabetes (“diabetes”) in New York City 1 Case 1:18-cv-06109 Document 1 Filed 11/01/18 Page 2 of 47 PageID #: 2 public schools, in violation of these students’ civil rights and resulting in short- and long-term harm. -

AlL BlAck LivEs MAtTer: Mental Health of Black LGBTQ Youth

All Black Lives Matter: Mental Health of Black LGBTQ Youth www.TheTrevorProject.org TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 About This Work 3 Methodology Summary 3 Key Findings 3 Recommendations 4 BACKGROUND 6 METHODOLOGY 7 RESULTS 8 Diversity among Black LGBTQ Youth 8 Mental Health and Well-being Among Black LGBTQ Youth 9 Black LGBTQ Youth’s Access to Care 11 Conversion Therapy and Change Attempts Among Black LGBTQ Youth 12 Housing Instability and Food Insecurities Among Black LGBTQ Youth 13 Discrimination and Victimization Among Black LGBTQ Youth 14 Support for Black LGBTQ Youth 15 RECOMMENDATIONS 18 About The Trevor Project 20 REFERENCES 21 Table: Black LGBTQ Youth Diversity 23 Page 2 of 22 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Black LGBTQ youth’s identification with multiple marginalized identities might make them more susceptible to negative experiences and decreased mental health. Both LGBTQ youth and Black youth report higher rates of poor mental health due to chronic stress stemming from the marginalized social status they have in U.S. society. However, very little research has quantitatively explored outcomes specific to Black LGBTQ youth. This report utilizes an intersectional lens to contribute to our understanding of the Black LGBTQ youth experience among a national sample of over 2,500 Black LGBTQ youth by highlighting and building upon many of the findings released from The Trevor Project’s National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health 2020 as they relate to Black LGBTQ youth. There is significant diversity within the Black LGBTQ youth community. ● 31% of Black LGBTQ youth identified as gay or lesbian, 35% as bisexual, 20% as pansexual, and 9% as queer ● One in three Black LGBTQ youth identified as transgender or nonbinary ● More than 1 in 4 Black LGBTQ youth use pronouns or pronoun combinations that fall outside of the binary construction of gender Black LGBTQ youth often report mental health challenges, including suicidal ideation. -

Poet Richard Blanco Keynotes National Archives LGBTQ Human and Civil Rights Discussion

NatIONAL TREASURES VOL 31, NO. 43 JULY 20, 2016 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Poet Richard Blanco. Photo by Kat Fitzgerald/www.MysticImagesPhotography.com Poet Richard Blanco keynotes National Archives LGBTQ Human and Civil Rights discussion BY Matt SIMONETTE sure that I belonged to America or what part of America be- longed to me,” Blanco said. Speaking at the Chicago History Museum July 16, poet Richard Blanco was the inaugural poet at President Barack Obama’s Blanco said that his work has long been dominated by a search second inauguration in 2013; he was the first openly gay per- for and a remembrance of “home,” adding that he frequently son, and the first immigrant, to fill that role. He was in Chi- evoked “a universal longing to ‘belong’ to someone or some- cago July 15-16 as part of the National Archive and Records BRIT BY BRIT place.” Administration’s (NARA) National Conversation on Rights and Growing up as part of a Cuban family in Miami, Blanco said Justice series, which this month focused on LGBT human and Talking with the stars of ‘Absolutely Fabulous: there were two representations of ‘home’ that frequently haunt- civil rights. The Movie.’ ed his imagination: Cuba, of which his exiled family frequently Blanco spoke about the importance of studying and preserv- Photo from Fox Searchlight spoke, and the generic representations of American families, ing historical documents, illustrating his point with a 1978 20 like the Brady Bunch, that populated afternoon TV reruns. “This was the only America that I thought existed. I wasn’t Turn to page 6 RACHEL WILLIAMS JIM FLINT RITA ADAIR Activist talks about BYP100, recent shootings. -

Anti-Bullying Resource Kit for Students Glaad.Org/Spiritday

YING RES I-BULL OURC NT E K A IT FOR STUDENTS OFFICIAL PARTNERS COMMUNITY PARTNERS If someone you know displays thoughts of suicide or other self-harm, call the Trevor Project Lifeline at 866-4-U-TREVOR (866-488-7386) to speak with a trained volunteer counselor. 1 Anti-Bullying Resource Kit For Students glaad.org/spiritday Contents 4 5 What is Spirit Day? How can I amplify my voice? inside cover t/k 66 7 Where can I find How can I be an ally online? anti-bullying resources? 88 9 How can I stay safe How can I share LGBTQ stories? on social media? 10 How can I promote transgender equality? 2 If someone you know displays thoughts of suicide or other self-harm, call the Trevor Project Lifeline at 866-4-U-TREVOR (866-488-7386) to speak with a trained volunteer counselor. If someone you know displays thoughts of suicide or other self-harm, call the Trevor Project Lifeline at 866-4-U-TREVOR (866-488-7386) to speak with a trained volunteer counselor. 3 Anti-Bullying Resource Kit For Students glaad.org/spiritday How can I amplify What is Spirit Day? my voice? tips for standing up when you see anti-LGBTQ bullying On October 17, 2019, millions will wear purple for Spirit Day as a symbol Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth often face of support for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth serious problems with bullying and harassment in America’s schools. What and to take a stand against bullying.