Florida's A++ Plan: an Expansion and Expression of Neoliberal and Neoconservative Tenets in State Educational Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Second Tea Party-Freedomworks Survey Report

FreedomWorks Supporters: 2012 Campaign Activity, 2016 Preferences, and the Future of the Republican Party Ronald B. Rapoport and Meredith G. Dost Department of Government College of William and Mary September 11, 2013 ©Ronald B. Rapoport Introduction Since our first survey of FreedomWorks subscribers in December 2011, a lot has happened: the 2012 Republican nomination contests, the 2012 presidential and Congressional elections, continuing debates over the budget, Obamacare, and immigration, and the creation of a Republican Party Growth and Opportunity Project (GOP). In all of these, the Tea Party has played an important role. Tea Party-backed candidates won Republican nominations in contested primaries in Arizona, Indiana, Texas and Missouri, and two of the four won elections. Even though Romney was not a Tea Party favorite (see the first report), the movement pushed him and other Republican Congressional/Senatorial candidates (e.g., Orin Hatch) to engage the Tea Party agenda even when they had not done so before. In this report, we will focus on the role of FreedomWorks subscribers in the 2012 nomination and general election campaigns. We’ll also discuss their role in—and view of—the Republican Party as we move forward to 2014 and 2016. This is the first of multiple reports on the March-June 2013 survey, which re-interviewed 2,613 FreedomWorks subscribers who also filled out the December 2011 survey. Key findings: Rallying around Romney (pp. 3-4) Between the 2011 and 2013 surveys, Romney’s evaluations went up significantly from 2:1 positive to 4:1 positive surveys. By the end of the nomination process Romney and Santorum had become the two top nomination choices but neither received over a quarter of the sample’s support. -

Journal of Media Law & Ethics

UNIVERSITY OF BALTIMORE SCHOOL OF LAW JOURNAL OF MEDIA LAW & ETHICS Editor ERIC B. EASTON, PROFESSOR EMERITUS University of Baltimore School of Law EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS BENJAMIN BENNETT-CARPENTER, Special Lecturer, Oakland Univ. (Michigan) STUART BROTMAN, Distinguished Professor of Media Management & Law, Univ. of Tennessee L. SUSAN CARTER, Professor Emeritus, Michigan State University ANTHONY FARGO, Associate Professor, Indiana University AMY GAJDA, Professor of Law, Tulane University STEVEN MICHAEL HALLOCK, Professor of Journalism, Point Park University MARTIN E. HALSTUK, Professor Emeritus, Pennsylvania State University CHRISTOPHER HANSON, Associate Professor, University of Maryland ELLIOT KING, Professor, Loyola University Maryland JANE KIRTLEY, Silha Professor of Media Ethics & Law, University of Minnesota NORMAN P. LEWIS, Associate Professor, University of Florida KAREN M. MARKIN, Dir. of Research Development, University of Rhode Island KIRSTEN MOGENSEN, Associate Professor, Roskilde University (Denmark) KATHLEEN K. OLSON, Professor, Lehigh University RICHARD J. PELTZ-STEELE, Chancellor Professor, Univ. of Mass. School of Law JAMES LYNN STEWART, Professor, Nicholls State University CHRISTOPHER R. TERRY, Assistant Professor, University of Minnesota DOREEN WEISENHAUS, Associate Professor, Northwestern University UB Journal of Media Law & Ethics, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2020) 1 Submissions The University of Baltimore Journal of Media Law & Ethics (ISSN1940-9389) is an on-line, peer- reviewed journal published quarterly by the University of Baltimore School of Law. JMLE seeks theoretical and analytical manuscripts that advance the understanding of media law and ethics in society. Submissions may have a legal, historical, or social science orientation, but must focus on media law or ethics. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. All manuscripts undergo blind peer review. -

The Religious Right and the Rise of the Neo-Conservatives, in an Oral Examination Held on May 10, 2010

AWKWARD ALLIES: THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT AND THE RISE OF THE NEO-CONSERVATIVES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Social and Political Thought University of Regina By Paul William Gaudette Regina, Saskatchewan July 2010 Copyright 2010: P.W. Gaudette Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88548-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-88548-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Fissures in Standards Formulation: the Role of Neoconservative and Neoliberal Discourses in Justifying Standards Development in Wisconsin and Minnesota

EDUCATION POLICY ANALYSIS ARCHIVES A peer-reviewed scholarly journal Editor: Sherman Dorn College of Education University of South Florida Volume 15 Number 18 September 10, 2007 ISSN 1068–2341 Fissures in Standards Formulation: The Role of Neoconservative and Neoliberal Discourses in Justifying Standards Development in Wisconsin and Minnesota Samantha Caughlan Michigan State University Richard Beach University of Minnesota Citation: Caughlan, S., & Beach, R. (2007). Fissures in standards formulation: The role of neoconservative and neoliberal discourses in justifying standards development in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 15(18). Retrieved [date] from http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v15n18/. Abstract An analysis of English/language arts standards development in Wisconsin and Minnesota in the late 1990s and early 2000s shows a process of compromise between neoliberal and neoconservative factions involved in promoting and writing standards, with the voices of educators conspicuously absent. Interpretive and critical discourse analyses of versions of English/language arts standards at the high school level and of public documents related to standards promotion reveal initial conflicts between neoconservative and neoliberal discourses, which over time were integrated in final standards documents. The content standards finally released for use in guiding curriculum in each state were bland and incoherent documents that reflected neither a deep knowledge of the field nor an acknowledgement of what is likely to engage young learners. The study suggests the need for looking more critically at standards as political documents, and a greater Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the author(s) and Education Policy Analysis Archives, it is distributed for non- commercial purposes only, and no alteration or transformation is made in the work. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Bridget Christine Gelms Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Dr. Jason Palmeri, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Tim Lockridge, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Michele Simmons, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Lisa Weems, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT VOLATILE VISIBILITY: THE EFFECTS OF ONLINE HARASSMENT ON FEMINIST CIRCULATION AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE by Bridget C. Gelms As our digital environments—in their inhabitants, communities, and cultures—have evolved, harassment, unfortunately, has become the status quo on the internet (Duggan, 2014 & 2017; Jane, 2014b). Harassment is an issue that disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color (Citron, 2014; Mantilla, 2015), LGBTQIA+ women (Herring et al., 2002; Warzel, 2016), and women who engage in social justice, civil rights, and feminist discourses (Cole, 2015; Davies, 2015; Jane, 2014a). Whitney Phillips (2015) notes that it’s politically significant to pay attention to issues of online harassment because this kind of invective calls “attention to dominant cultural mores” (p. 7). Keeping our finger on the pulse of such attitudes is imperative to understand who is excluded from digital publics and how these exclusions perpetuate racism and sexism to “preserve the internet as a space free of politics and thus free of challenge to white masculine heterosexual hegemony” (Higgin, 2013, n.p.). While rhetoric and writing as a field has a long history of examining myriad exclusionary practices that occur in public discourses, we still have much work to do in understanding how online harassment, particularly that which is gendered, manifests in digital publics and to what rhetorical effect. -

George W Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey.Pdf

Intermountain Region National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior August 2015 GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME Reconnaissance Survey Midland, Texas Front cover: President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush speak to the media after touring the President’s childhood home at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, on October 4, 2008. President Bush traveled to attend a Republican fundraiser in the town where he grew up. Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images CONTENTS BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE — i SUMMARY OF FINDINGS — iii RECONNAISSANCE SURVEY PROCESS — v NPS CRITERIA FOR EVALUATION OF NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE — vii National Historic Landmark Criterion 2 – viii NPS Theme Studies on Presidential Sites – ix GEORGE W. BUSH: A CHILDHOOD IN MIDLAND — 1 SUITABILITY — 17 Childhood Homes of George W. Bush – 18 Adult Homes of George W. Bush – 24 Preliminary Determination of Suitability – 27 HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF THE GEORGE W. BUSH CHILDHOOD HOME, MIDLAND TEXAS — 29 Architectural Description – 29 Building History – 33 FEASABILITY AND NEED FOR NPS MANAGEMENT — 35 Preliminary Determination of Feasability – 37 Preliminary Determination of Need for NPS Management – 37 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS — 39 APPENDIX: THE 41ST AND 43RD PRESIDENTS AND FIRST LADIES OF THE UNITED STATES — 43 George H.W. Bush – 43 Barbara Pierce Bush – 44 George W. Bush – 45 Laura Welch Bush – 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY — 49 SURVEY TEAM MEMBERS — 51 George W. Bush Childhood Home Reconnaissance Survey George W. Bush’s childhood bedroom at the George W. Bush Childhood Home museum at 1421 West Ohio Avenue, Midland, Texas, 2012. The knotty-pine-paneled bedroom has been restored to appear as it did during the time that the Bush family lived in the home, from 1951 to 1955. -

The Green Web: Evaluating Online News Communities and Their

THE GREEN WEB: EVALUATING ONLINE NEWS COMMUNITIES AND THEIR ENVIRONMENTALISM By Stian Himberg Roussell A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Science: Environment and Community Committee Membership Dr. Anthony Silvaggio, Committee Chair Dr. Nikola Hobbel, Committee Member Dr. John Meyer, Committee Member Dr. Mark Baker, Program Graduate Coordinator July 2019 ABSTRACT THE GREEN WEB: EVALUATING ONLINE NEWS COMMUNITIES AND THEIR ENVIRONMENTALISM Stian Himberg Roussell In the past news and media were disseminated through channels that were difficult for consumers to communicate with. Now a new form of news dissemination is taking place on the internet where communication between consumers and producers exists. Crowdsourced social media sites, where users elect and vote on articles and comments to represent a topic, are creating new forms of news dissemination which heavily alters media content and community discussions. This study was conducted in order to better understand how crowdsourced social media platforms affect users’ perception of environmental topics, issues, and problems. It focuses on the crowdsourced social media platform Reddit evaluating the top 100 articles within the subreddit titled r/environment. The methods used in this study include secondary data analysis, archival research of online forums, and social network analysis. Most articles analyzed discussed the topic of politics, including President Trump and his administration’s environmental policies, as well as a lack of transparency related to environmental policies in general. Many of the comments responded to these articles by discussing politics. Findings also included a perception that monetary and social capital must be present for individuals to facilitate widescale, meaningful environmental change. -

JOHN WEAVER – Chief Strategist Overview

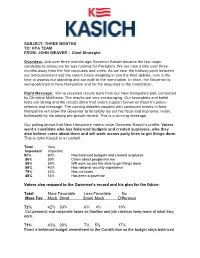

SUBJECT: THREE MONTHS TO: KFA TEAM FROM: JOHN WEAVER – Chief Strategist Overview: Just over three months ago Governor Kasich became the last major candidate to announce he was running for President. We are now a little over three months away from the first caucuses and votes. As we near the halfway point between our announcement and the voters finally weighing in and the third debate, now is the time to assess our standing and our path to the nomination. In short, the Governor is well-positioned in New Hampshire and for the long road to the nomination. Right Message: We’ve received results back from our New Hampshire poll, conducted by Christine Matthews. The results are very encouraging. Our favorables and ballot tests are strong and the results show that voters support Governor Kasich’s policy reforms and message. The coming debates coupled with continued events in New Hampshire will allow the Governor to forcefully lay out his fiscal and economic vision, buttressed by his strong pro-growth record. This is a winning message. Our polling shows that New Hampshire voters value Governor Kasich’s profile. Voters want a candidate who has balanced budgets and created surpluses, who they also believe cares about them and will work across party lines to get things done. This is John Kasich in a nutshell. Total Very Important Important 92% 60% Has balanced budgets and created surpluses 86% 59% Cares about people like me 85% 59% Will work across the aisle to get things done 84% 40% Has national security experience 79% 42% Has cut taxes 48% 14% Has been a governor Voters also respond to the Governor’s record and his plan for the future: Total More Favorable Less Favorable No More Fav Much Smwt Smwt Much Difference 72% 42% 30% 6% 4% 19% Cut personal and corporate taxes so families and job creators keep more of what they earn. -

John Mccain: a Third Term for the Bush Agenda

The McCain U Syllabus Table of Contents Introduction • MEMO: John McCain: A Third Term for the Bush Agenda Chapter 1: Economy • The Winning Argument: John McCain’s Economic Policies • REPORT: McCain Adopts ‘Entire’ Norquist Agenda, Will Double The Bush Tax Cuts • What You Need To Know About McCain’s Economic Plan • McCain Would Give America’s 200 Largest Corporations $45 Billion In Tax Breaks • McCain’s Budget Would Create Largest Deficit In 25 Years, Largest Debt Since WWII • Earmark Accounting Leaves Two Thirds Of McCain Tax Proposal Unfunded • Sen. McCain's HOME Plan: Late to the Party with a Flawed Plan • John and Cindy McCain would reap $373,429 if McCain’s tax proposal were enacted • Income Disparity And Wealth Consolidation Show Eerie Resemblances To 1928 • Ex-Reagan Official: McCain Claim On Corporate Expensing Is ‘So Intellectually Dishonest It’s Outrageous’ • Douglas Holtz-Eakin Vs. Douglas Holtz-Eakin On Corporate Expensing • The McCain Deficit: Douglas Holtz-Eakin Continues To Debate With Himself Chapter 2: Health care • The Winning Argument: John McCain’s Health Care Proposals • Elizabeth Edwards: Why Are People Like Me Left Out Of Your Health Care Proposal, Sen. McCain? • Elizabeth Edwards On The Inequitable Individual Market • What You Need To Know About McCain’s Health Care Plan • REPORT: McCain Plan Doles Out $2 Billion In Tax Cuts For The Biggest Health Insurers • John McCain’s Health Care Plan Means High Paperwork Costs • McCain’s Cost-Containment Plan: Reduce Access to Health Insurance • McCain’s Health Care Death -

Think Progress EXCLUSIVE: US Chamber’S Lobbyists Solicited Hackers to Sabotage Unions, Smear Chamber’S Political Opponents

ThinkProgress » EXCLUSIVE: US Chamber’s Lobbyists Solicited Hackers To Sabotage Unions,... Page 1 of 2 Think Progress EXCLUSIVE: US Chamber’s Lobbyists Solicited Hackers To Sabotage Unions, Smear Chamber’s Political Opponents By Lee Fang on Feb 10th, 2011 at 4:30 pm EXCLUSIVE: US Chamber’s Lobbyists Solicited Hackers To Sabotage Unions, Smear Chamber’s Political Opponents ThinkProgress has learned that a law firm representing the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the big business trade association representing ExxonMobil, AIG, and other major international corporations, is working with set of “private security” companies and lobbying firms to undermine their political opponents, including ThinkProgress, with a surreptitious sabotage campaign. According to e-mails obtained by ThinkProgress, the Chamber hired the lobbying firm Hunton and Williams. Hunton And Williams’ attorney Richard Wyatt, who once represented Food Lion in its infamous lawsuit against ABC News, was hired by the Chamber in October of last year. To assist the Chamber, Wyatt and his associates, John Woods and Bob Quackenboss, solicited a set of private security firms — HBGary Federal, Palantir, and Berico Technologies (collectively called Team Themis) — to develop tactics for damaging progressive groups and labor unions, in particular ThinkProgress, the labor coalition called Change to Win, the SEIU, US Chamber Watch, and StopTheChamber.com. According to one document prepared by Team Themis, the campaign included an entrapment project. The proposal called for first creating a “false document, perhaps highlighting periodical financial information,” to give to a progressive group opposing the Chamber, and then to subsequently expose the document as a fake to undermine the credibility of the Chamber’s opponents. -

Conspiracy Theories.Pdf

Res earc her Published by CQ Press, a Division of SAGE CQ www.cqresearcher.com Conspiracy Theories Do they threaten democracy? resident Barack Obama is a foreign-born radical plotting to establish a dictatorship. His predecessor, George W. Bush, allowed the Sept. 11 attacks to P occur in order to justify sending U.S. troops to Iraq. The federal government has plans to imprison political dissenters in detention camps in the United States. Welcome to the world of conspiracy theories. Since colonial times, conspiracies both far- fetched and plausible have been used to explain trends and events ranging from slavery to why U.S. forces were surprised at Pearl Harbor. In today’s world, the communications revolution allows A demonstrator questions President Barack Obama’s U.S. citizenship — a popular conspiracists’ issue — at conspiracy theories to be spread more widely and quickly than the recent “9-12 March on Washington” sponsored by the Tea Party Patriots and other conservatives ever before. But facts that undermine conspiracy theories move opposed to tax hikes. less rapidly through the Web, some experts worry. As a result, I there may be growing acceptance of the notion that hidden forces N THIS REPORT S control events, leading to eroding confidence in democracy, with THE ISSUES ......................887 I repercussions that could lead Americans to large-scale withdrawal BACKGROUND ..................893 D from civic life, or even to violence. CHRONOLOGY ..................895 E CURRENT SITUATION ..........900 CQ Researcher • Oct. 23, 2009 • www.cqresearcher.com AT ISSUE ........................901 Volume 19, Number 37 • Pages 885-908 OUTLOOK ........................902 RECIPIENT OF SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SILVER GAVEL AWARD BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................906 THE NEXT STEP ................907 CONSPIRACY THEORIES CQ Re search er Oct. -

Is George W Bush a Burden Or Blessing for Jeb Bush's 2016

Boise State University ScholarWorks Political Science Faculty Publications and Department of Political Science Presentations 6-15-2015 Is George W Bush a Burden or Blessing for Jeb Bush’s 2016 Campaign? Justin S. Vaughn Boise State University Academic rigor, journalistic flair Is George W Bush a burden or blessing for Jeb Bush’s 2016 campaign? June 15, 2015 1.35pm EDT Author Justin S. Vaughn Assistant Professor , Boise State University To hug or not to hug? Jason Reed/Reuters Now that Jeb Bush has finally officially announced his bid for the White House, the chattering class can shift its conversation to whether he will win and what hurdles stand in his way. The people in his way Anyone paying attention to the 2016 scuttlebutt can give you the names of some of the bigger obstacles in his path to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Perhaps the most obvious would be Hillary Clinton, who will almost certainly be the Democratic nominee despite the best efforts of Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley. Indeed, in the dozens of major national polls that have tracked opinion dynamics about likely 2016 matchups, Clinton has beaten Bush in all but one, a recent FOX News poll that showed the former Florida governor leading by only one point, within the margin of error. Those savvy to what political scientists call “the invisible primary” would likely also suggest the names Rand Paul, Scott Walker, and Marco Rubio, who have so far shaped up to be Bush’s key opponents in the run for the Republican Party’s nomination. Although Bush has routinely polled in the double digits over the past several months, his numbers in most major polls have remained relatively flat, if not on a slight decline, showing that, if nothing else, Bush has so far been unable to separate himself from the pack.