NYSDEC Region 9 Trout Stream Monitoring Summary for 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genesee Valley Greenway State Park Management Plan Existing

Genesee Valley Greenway State Park Management Plan Part 2 – Existing Conditions and Background Information Part 2 Existing Conditions and Background Information Page 45 Genesee Valley Greenway State Park Management Plan Part 2 – Existing Conditions and Background Information Existing Conditions Physical Resources Bedrock Geology From Rochester heading south to Cuba and Hinsdale Silurian Akron Dolostone, Cobleskill Limestone and Salina Group Akron dolostone Camillus Shale Vernon Formation Devonian Onondaga Limestone and Tri-states Group Onondaga Limestone Hamilton Group Marcellus Formation Skaneatleles Formation Ludlowville Formation Sonyea Group Cashaqua Shale Genesee Group and Tully Limestone West River Shale West Falls Group Lower Beers Hill West Hill Formation Nunda Formation Java Group Hanover Shale Canadaway Group Machias Formation Conneaut Group Ellicot Formation Page 47 Genesee Valley Greenway State Park Management Plan Part 2 – Existing Conditions and Background Information Soils As much of the Greenway follows the route of the Rochester Branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad, major expanses of the Greenway Trail are covered with a layer of cinder and/or turf and other man-made fill. In general, the soils underneath the Greenway tend to be gravelly or silty clay loam. The entire trail is fairly level, with the majority of slopes being less than five percent. A complete, narrative description of the soils can be found in Appendix F Natural Resources Flora A complete biological inventory of Greenway property is not presently available (October 2013). However, SUNY Geneseo botany students began to inventory flora within sections of the corridor. The New York State Natural Heritage Program has targeted the GVG for a Natural Heritage inventory in 2014. -

Lake Ontario Maps, Facts and Figures

Lake Ontario maps, facts and figures A project by the FINGER LAKES-LAKE ONTARIO WATERSHED PROTECTION ALLIANCE and NEW YORK SEA GRANT 1. Origins of Lake Ontario Direct Drainage Basin 2. Population by Census Block Groups 3. Detailed Surface Water New York’s Lake Ontario . shown in maps, facts & figures Lake Ontario, the 14th largest lake in the world, is the smallest of the Great 4. Topography Lakes. Bordered to the north by Ontario, Canada, and to the south by New York State, it is the smallest in surface area, fourth among the Great Lakes in maximum depth, but second only to Lake Superior in average depth. The basin land area is largely rural with a significant forested and Lake Ontario at a glance 5. Land Use Types agricultural portion. The Lake is nestled between the mighty Niagara River Lake Ontario is the 14th largest lake in the world. to the west...and the picturesque St. Lawrence River Valley to its east. Length: 193 mi / 311 km Width: 53 mi / 85 km Almost one-third of the land area of New York State drains Published by Finger Lakes-Lake Ontario Watershed Protection Alliance (FLLOWPA) Average depth: 283 ft / 86 m 6. Wastewater Treatment Plants and New York Sea Grant. into Lake Ontario, making the wise use and management of Maximum depth: 802 ft / 244 m All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval natural resources vital to the long-term sustainability of the system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, 3 3 photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. -

Genesee Valley Glacial and Postglacial Geology from 50000

Genesee Valley Glacial and Postglacial Geology from 50,000 Years Ago to the Present: A Selective Annotated Review Richard A. Young, Department of Geological Sciences, SUNY, Geneseo, NY 14454 Introduction The global chronology for The Pleistocene Epoch, or “ice age,” has been significantly revised during the last three decades (Alley and Clark, 1999) as a result of the extended and more accurate data provided by deep sea drilling projects, ice core studies from Greenland and Antarctica (Andersen et al. 2006; Svensson et al. 2008), oxygen isotope studies of marine sediments, and climatic proxy data from lake cores, peat bogs, and cave stalactites. These new data have improved our ability to match the Earth’s Milankovitch orbital cycles to the improved ice core and radiometric chronologies (ages based on radiocarbon, U-Th, U-Pb). However, the Milankovitch theory has recently been the subject of renewed controversy, and not all cyclical climatic phenomena are directly reconcilable with Milankovitch’s original ideas (Ridgwell et al., 1999; Ruddiman, 2006). Overall, it is evident that there must have been as many as 20 or more glacial cycles in the last 2.5 million years, not all of which necessarily resulted in the expansion of large ice sheets as far south as the United States-Canadian border. The International Union of Geological Sciences recently adopted a change for the Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary, extending the beginning of the Pleistocene Epoch back from 1.8 to 2.588 million years Before Present (BP). The average length of the most recent glacial- interglacial cycles (also known as “Stages”) is on the order of 100,000 years, with 10,000 to 15,000 years being the approximate length of the interglacial warm episodes between the longer cold cycles (also known as cold stadials and warm interstadials). -

Draft Port of Rochester & Genesee River Harbor Management Plan

2016 Draft Port of Rochester & Genesee River Harbor Management Plan This report was prepared with funding provided by the New York State Department of State under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund. Photos provided by NYS DOS and City of Rochester Port of Rochester-Genesee River Harbor Management Plan City of Rochester, New York Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 1 1.1 PURPOSE & BENEFIT OF THE HARBOR MANAGEMENT PLAN ........................................................... 1 1.2 LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY FOR LOCAL HARBOR MANAGEMENT......................................................... 2 1.2.1 The HMP as a Component of the Local Waterfront Revitalization Program ................. 2 1.3 HARBOR MANAGEMENT AREA ................................................................................................. 3 1.3.1 Harbor Management Area ............................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Port of Rochester and Rochester Harbor Designations ................................................. 6 1.3.3 Port Redevelopment Project .......................................................................................... 6 1.3.4 HMA Historical Context ................................................................................................. 7 1.4 PUBLIC & STAKEHOLDER OUTREACH DURING HMP PREPARATION ................................................ 15 1.4.1 Project Advisory Committee Meetings ....................................................................... -

Upper Devonian Depositional and Biotic Events in Western New York

MIDDLE- UPPER DEVONIAN DEPOSITIONAL AND BIOTIC EVENTS IN WESTERN NEW YORK Gordon C. Baird, Dept. of Geosciences, SUNY-Fredonia, Fredonia, NY 14063; D. Jeffrey Over, Dept. of Geological Sciences, SUNY-Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454; William T. Kirch gasser, Dept. of Geology, SUNY-Potsdam, Potsdam, NY 13676; Carlton E. Brett, Dept. of Geology, Univ. of Cincinnati, 500 Geology/Physics Bldg., Cincinnati, OH 45221 INTRODUCTION The Middle and Late Devonian succession in the Buffalo area includes numerous dark gray and black shale units recording dysoxic to near anoxic marine substrate conditions near the northern margin of the subsiding Appalachian foreland basin. Contrary to common perception, this basin was often not stagnant; evidence of current activity and episodic oxygenation events are characteristic of many units. In fact, lag deposits of detrital pyrite roofed by black shale, erosional runnels, and cross stratified deposits of tractional styliolinid grainstone present a counter intuitive image of episodic, moderate to high energy events within the basin. We will discuss current-generated features observed at field stops in the context of proposed models for their genesis, and we will also examine several key Late Devonian bioevents recorded in the Upper Devonian stratigraphic succession. In particular, two stops will showcase strata associated with key Late Devonian extinction events including the Frasnian-Famennian global crisis. Key discoveries made in the preparation of this field trip publication, not recorded in earlier literature, -

The Lost City of Tryon Trail Is an Approved Historic Trail Of

The Lost City of Tryon Trail is an approved Historic Trail of the Boy Scouts of America and is administered by the Seneca Waterways Council Scouting Historical Society. It offers hikers a fantastic opportunity to experience a geographic location of enduring historic significance in Upstate New York. 2018 EDITION Seneca Waterways Council Scouting Historical Society 2320 Brighton-Henrietta Town Line Road, Rochester, NY 14623 version 2.0 rdc 10/2018 A Nice Hike For Any Season Introduction The Irondequoit Bay area was once at the crossroads of travel and commerce for Native Americans. It was the home of the Algonquin and later the Seneca, visited by a plethora of famous explorers, soldiers, missionaries and pioneers. This guidebook provides only a small glimpse of the wonders of this remote wilderness prior to 1830. The Lost City of Tryon Trail takes you through a historic section of Brighton, New York, in Monroe County’s Ellison Park. The trail highlights some of the remnants of the former City of Tryon (portions of which were located within the present park) as well as other historic sites. It was also the location of the southernmost navigable terminus of Irondequoit Creek via Irondequoit Bay, more commonly known as “The Landing.” The starting and ending points are at the parking lot on North Landing Road, opposite the house at #225. Use of the Trail The Lost City of Tryon Trail is located within Ellison Park and is open for use in accordance with park rules and regulations. Seasonal recreation facilities, water, and comfort stations are available. See the park’s page on the Monroe County, NY website for additional information. -

New York State Council Trout Unlimited

New York State Council Trout Unlimited Our mission is “To conserve, protect, restore and sustain New York coldwater fisheries and their watersheds, especially our wild trout resources” We restore streams through habitat improvement projects, conduct seminars on water quality and fisheries management, and work to educate the next generation about the importance of clean water and wild trout. Trout Unlimited NY • 8,000 members • 31 chapters Trout Unlimited Chapters in the Genesee Basin • 5 chapters in the Genesee Basin • 1,000 members http://tu-newyorkcouncil.org/ 1 New York State Council Regions Map Region 6 Vice President Paul Miller Region 7 Vice President Region 5 Vice President Open Position Rich Redman Region 9 Vice President Chuck Godfrey Region 4 Vice President Vince Dubois Region 8 Vice President Region 1 Vice President Jim Palmer George Costa Region 3 Vice President Bill Shaw Region 2 Vice President Roger Olsen http://tu-newyorkcouncil.org/ New York State Council Trout Unlimited Executive Team Chairman Larry Charette Conservation Fund Treasurer NLC Secretary Chairman Vice Chair Scott Seidman Mike Mowins Jeff Plackis Dave Savko William Strugatz Region 1 Vice President Region 2 Vice President Region 3 Vice President Region 4 Vice President Region 5 Vice President George Costa Roger Olson Bill Shaw Vince Dubois Rich Redman Chairman Region 6 Vice President Region 8 Vice President Region 9 Vice President Fisheries Enhancement Region 7 Vice President Paul Miller Jim Palmer Chuck Godfrey Fund Committee Don Keiffer Resource Management -

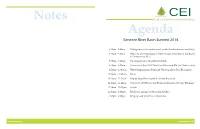

Genesee River Basin Summit 2014

Notes Center for Environmental Initiatives Agenda Genesee River Basin Summit 2014 8:00am - 8:45am Participants arrive and network (coffee & refreshments available) 8:45am - 8:55am Welcome and Introduction (Mike Haugh, President of the Board of Directors for CEI) 8:55am - 9:10am Opening Speaker (Corydon Ireland) 9:10am - 9:50am Overview of the SWAT Model and Research (Dr. Joe Makarewicz) 9:50am - 10:30am Water Management/Regional Water Quality (Ron Entringer) 10:30am - 10:45am Break 10:45am - 11:15am Empire State Development (Vinnie Esposito) 11:15pm - 11:45am Overview and Process for Break-out Sessions (George Thomas) 11:45am - 12:30pm Lunch 12:30pm - 3:30pm Break Out Groups (with cookie breaks) 3:30pm - 4:30pm Wrap up and prioritize action items www.ceinfo.org www.ceinfo.org Recent projects include the TMDLs for Onondaga and Chautauqua Lakes, Port, Blind Sodus and Little Sodus Bays on Lake Ontario, and the first nutrient TMDL for flowing waters in Black Creek. From 1973 to 1985, he worked for Erie County Department of Environment and Planning, and consultants in four other states on a variety of water quality and watershed projects.” Corydon Ireland Bio’s Vinnie Esposito Journalist and amateur historian Corydon Ireland, a fourth-generation native of Upstate New York, is in his eighth year as a features writer in the news office at Harvard University. His newspaper career started in Niagara Falls, where he reported on Love Canal, and Vinnie Esposito is the Executive Director of the Finger Lakes Regional Economic Development Council and of Empire State included 13 years at the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, where he was a longtime environment reporter. -

Inland Trout Stocking 2021

Region 9 Fisheries Unit Caledonia Hatchery Randolph Hatchery 182 E. Union, Suite 3 585-538-6300 716-358-4755 Allegany, NY 14706 716-372-0645 (Last updated: 3/31/2021) INLAND TROUT STOCKING 2021 * Species BT - brown trout RT - rainbow trout ST - brook trout 2YBT - two year old Brown trout (13-15” fish) - all others are spring yearlings in lakes (8-9” fish) and 9” fish in streams ** Subject to change due to water conditions Note, stockings are listed by week, not by day. ALLEGANY COUNTY Week Stocked** Water Section Species* Number From 0.5 mi downstream of Sanford Hollow Rd upstream to 0.6 mi Week of 3/22/2021 Little Genesee Creek upstream of 2nd Co 9” STY 1920 Rt 8 (Invale Rd) crossing Little Genesee Creek Same section 2YBT 210 From Co Rt 33 upstream to 0.5 mi California Hollow Brook upstream of 9” BTY 440 confluence with Kansas Hollow California Hollow Brook Same section 2YBT 50 From confluence with Little Genesee Ck upstream to 350 yards Root Creek upstream of 2YBT 40 Black/George Hollow Rd Root Creek Same section 9” RTY 390 From S. Broad St in Wellsville upstream to Dyke Creek 0.5 mi upstream of 2YBT 180 Ray Hill Rd Dyke Creek Same section 9” RTY 1650 From NY/PA line upstream to Cryder Creek confluence with 9” BTY 1400 Wileyville Ck in Whitesville Cryder Creek Same section 2YBT 160 From NYS Route 19 Bridge in Shongo Genesee River Upstream To State 2YBT 60 Line Genesee River Same section 9” RTY 570 From County Route 29 near York's Genesee River Corners upstream to 2YBT 40 NYS Route 19 in Shongo Genesee River Same section 9” RTY 330 From Belmont Dam in Belmont upstream to Genesee River County Route 29 near 9” RTY 4960 York's Corners Genesee River Same section 2YBT 550 From Temple St Dodge Creek upstream to Rt 305 in 9” RTY 1950 W. -

Miles FIELD TRIP NO. JA -- Hamilton Stratigraphy and Fossil Collecting

FIELD TRIP NO. JA -- Hamilton Stratigraphy and Fossil Collecting Exposures of the Ludlowville formation will be visited in an area south of Batavia. The Centerfield member here is prolifically fossiliferous and the relationships of the other Ludlowville members (except the Deep Run) are clearly shown across the Clarendon-Linden monocline. Miles 0.0 Zero mileage, River Blvd. entrance to main quadrangle of U of R, River Campus, as for previous trips. 0 0 25 Elmwood Avec (N.Y. 47). Turn right over Genesee River bridge. 0 0 5 N.Yo 383 (Plymouth Ave .. ) joins from right. Cross railroad tracks. 0 0 7 Follow N.Yo 383 to left onto Scottsville Rd. 1 .. 1 Erie Canal 1 .. 8 Rochester-Monroe County Airport to right. 3.0 N.Y. 252 joins from right. Bear left. 3 .. 1 Pass over railroad. 308 New York Central Railroad branch line crossing and bridge. 402 N.Yo 252 leaves to left over steel truss bridge. 6.3 Road swings away from Genesee River. Ascends Dumpling Hill, a drumlin whose northeast end is truncated by the Genesee. 808 Pass under New York State Thruway. 902 Pass over railroad. 10 0 1 Turn right (W) on North Rd. at beginning of settlement (Scottsville). Now over Upper Silurian; no exposures. 1007 Railroad crossing .. 1104 scottsville-Chili Rd. Keep straight. Several gravel pits in glacial material to left after crossing. 14 0 0 Wheatland Center Rd. Turn left (s). 1405 Stop sign. NoYo 383. Turn right (W). Wooded drumlin at left after making turn 0 Behind (S of) drumlin is shallow gypsum mine in Upper Silurian . -

Bring the Family.Closer

L OGO V ARIA T ION S Black background field is provided for visual reference. This is not part of the reversed logo design. FULL L OGO WIT H T A G L OGO ON D ARK ER BA C K GROUND The full logo with tag should be used at all times during the implementation phase. If questions arise, please contact the communications department. bring the family. closer. L OGO WITHOU T T A G S IMPLIFIE D V ERSION / L OGO WITH ROCHE S TER T A G SIMPLIFIED LOGO One-of-a-kind museums. Unique themed attractions. Terrific theater WITHand ROCHE theSTER TA G incredible drama of Use when distributing or implementing the simplified sports. The hidden gem of Western New York is waiting to shine brightlogo onfor marketing you. materials Use this helpful guide outside the Rochester region. The version with the words “Rochester, NY” to plan your next trip to Rochester and bring the family closer to the shouldextraordinary be used. This option and to each other. is intended to reinforce the brand to those who G REY S CALE V ERS ION REV ERSED V ERS ION are unfamiliar with the organization outside the Rochester region. Events (Continued) • Rochester Lilac Festival • Whispering Pines Miniature Golf 30% GREY • Corn Hill Summer Arts Festival • Wickham Farms 30% GREY • CGI International Jazz Festival • Park Avenue Summer Arts Festival Museums, Cultural, and Historical • Key Bank Rochester Fringe Festival Institutions • Genesee Country Village & Museum • George Eastman Museum Agritourism, Outdoor Fun, and Swimming • George W. Cooper International Doll • Adventure Landing Miniature Golf and Collection at the Central Library Fun Center • Jell-O Gallery • Bay Creek Paddling Center • Memorial Art Gallery • Braddock Bay Raptor Research • National Susan B. -

Thursday, October 5, 2017 Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge 9:00 – 11:00 Am PRISM News & Updates

WNY PRISM FALL PARTNER MEETING 2017 Thursday, October 5, 2017 Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge 9:00 – 11:00 am PRISM News & Updates Staff • Invasive Species Management Assistants (finished up) • ESF/DEC Survey & Monitoring Intern (finished up) • Education & Outreach Assistant finishes next week (10/13) • Hired Project Manager – Lucy Nuessle • Currently hiring Slender False Brome Manager Program • WNY PRISM NCTE was approved by DEC – funding through 2018 PRISM News & Updates Staff • Invasive Species Management Assistants finished up • Education & Outreach Assistant finishes next week (10/13) • Hired Project Manager – Lucy Nuessle • Currently hiring Slender False Brome Manager Program • WNY PRISM NCTE was approved by DEC – funding through 2018 2017 Field Season – removal projects • Niagara Escarpment Preserve • Seneca Bluffs • Audubon Community Nature Center • Tifft Vernal Pools • Woodlawn Beach State Park • North Tonawanda Audubon Nature Preserve • College Lodge • Bergen Swamp • Niagara County Knotweed 2017 Field Season – volunteer workdays • Common buckthorn removal at North Tonawanda Audubon Nature Preserve • Mugwort removal at Kenneglenn • Yellow flag iris removal at Fuhrman Fen • Japanese barberry & multi-flora rose at Franklin Gulf County Park • Native planting at Seneca Bluffs 2017 Field Season - outreach • Party for the Planet – Buffalo Zoo • Farmers’ Markets • Lockport • Hamburg • Salamanca • Alfred • Genesee County • Orleans County Fair • Insectival –Tifft • Clarence Hollows Monarch Release • Fall Festival Reinstein Woods • ALB