Is Yogic Enlightenment Dependent Upon God?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review:" Yoga Body: the Origins of Modern Posture Practice"

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 23 Article 17 January 2010 Book Review: "Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice" Harold Coward Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Coward, Harold (2010) "Book Review: "Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice"," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 23, Article 17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1469 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Coward: Book Review: "Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice" 62 Book Reviews There is much to be learned from and seem to reflect a presumed position of privilege appreciated in Schouten's Jesus as Guru. for Caucasian, WesternlEuropean, Christian However, I was frustrated by phrases such as contexts. "Whoever explores the religion and culture of While dialogue between "East" and "West" India comes fact to face with a different world," sets the context for the book in the introduction, (1) or " ... Since then, it is no longer possible to in the Postscript Schouten acknowledges, " .. .in i imagine Indian society and culture without the past quarter of a century the voice of Hindus i I Christ." (4) Following an informative in the dialogue has grown silent." (260) Perhaps intermezzo on Frank Wesley's depiction of future work can assess why this might be so and Jesus as a blue hued child like Krishna, I wonder work to build a new conversation. -

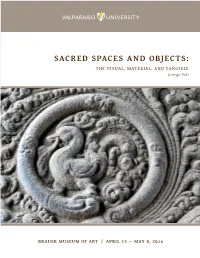

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

The Potentials and Prospects of Yoga Pilgrimage Exploration in Bali Tourism

International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Volume 8 Issue 8 Article 11 2020 The Potentials and Prospects of Yoga Pilgrimage Exploration in Bali Tourism I GEDE SUTARYA Universitas Hindu Negeri I Gusti Bagus Sugriwa Denpasar, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp Part of the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation SUTARYA, I GEDE (2020) "The Potentials and Prospects of Yoga Pilgrimage Exploration in Bali Tourism," International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: Vol. 8: Iss. 8, Article 11. doi:https://doi.org/10.21427/05cm-qk98 Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol8/iss8/11 Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. The Potentials and Prospects of Yoga Pilgrimage Exploration in Bali Tourism Cover Page Footnote This article is based on research about yoga tourism in Bali, Indonesia. We express our thanks to the Chancellor of Universitas Hindu Negeri I Gusti Bagus Sugriwa Denpasar, Prof.Dr. IGN. Sudiana, Dean of Dharma Duta Faculty, Dr. Ida Ayu Tary Puspa and head of the Research and Community Service, Dr. Ni Ketut Srie Kusuma Wardani for their support. This academic paper is available in International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/vol8/iss8/11 © International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage ISSN : 2009-7379 Available at: http://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijrtp/ Volume 8(viii) 2020 The Potentials and Prospects of Yoga Pilgrimage Exploration in Bali Tourism I Gede Sutarya Universitas Hindu Negeri I Gusti Bagus Sugriwa Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia [email protected] Yoga tourism has been growing rapidly in Bali since the 2000s. -

An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health

WHOLE HEALTH: INFORMATION FOR VETERANS An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health Whole Health is an approach to health care that empowers and enables YOU to take charge of your health and well-being and live your life to the fullest. It starts with YOU. It is fueled by the power of knowing yourself and what will really work for you in your life. Once you have some ideas about this, your team can help you with the skills, support, and follow up you need to reach your goals. All resources provided in these handouts are reviewed by VHA clinicians and Veterans. No endorsement of any specific products is intended. Best wishes! https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/ An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health SUMMARY 1. One of the main goals of yoga is to help people find a more balanced and peaceful state of mind and body. 2. The goal of yoga therapy (also called therapeutic yoga) is to adapt yoga for people who may have a variety of health conditions or needs. 3. Yoga can help improve flexibility, strength, and balance. Research shows it may help with the following: o Decrease pain in osteoarthritis o Improve balance in the elderly o Control blood sugar in type 2 diabetes o Improve risk factors for heart disease, including blood pressure o Decrease fatigue in patients with cancer and cancer survivors o Decrease menopausal hot flashes o Lose weight (See the complete handout for references.) 4. Yoga is a mind-body activity that may help people to feel more calm and relaxed. -

The Concept of Bhakti-Yoga

Nayankumar J. Bhatt [Subject: English] International Journal of Vol. 2, Issue: 1, January 2014 Research in Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X The Concept of Bhakti-Yoga NAYANKUMAR JITENDRA BHATT B-402, Ayodhya Appt., Maheshnagar, Zanzarada Road, Junagadh Gujarat (India) Abstract: Bhakti-Yoga is a real, genuine search after the lord, a search beginning, continuing, and ending in love. One single moment of the madness of extreme love to God brings us eternal freedom. About Bhakti-Yoga Narada says in his explanation of the Bhakti-aphorisms, “is intense love to God.” When a man gets it, he loves all, hates none; he becomes satisfied forever. This love cannot be reduced to any earthly benefit, because so long as worldly desires last, that kind of love does not come. Bhakti is greater than Karma, because these are intended for an object in view, while Bhakti is its own fruition, its own means, and its own end. Keywords: Bhakti Yoga, God, Karma, Yoga The one great advantage of Bhakti is that it is the easiest, and the most natural way to reach the great divine end in view; its great disadvantage is that in its lower forms it oftentimes degenerates into hideous fanaticism. The fanatical crews in Hinduism, or Mohammedanism, or Christianity, have always been almost exclusively recruited from these worshippers on the lower planes of Bhakti. That singleness of attachment to a loved object, without which no genuine love can grow, is very often also the cause of the denunciation of everything else. When Bhakti has become ripe and has passed into that form which is caned the supreme, no more is there any fear of these hideous manifestations of fanaticism; that soul which is overpowered by this higher form of Bhakti is too near the God of Love to become an instrument for the diffusion of hatred. -

Tantra and Hatha Yoga

1 Tantra and Hatha Yoga. A little history and some introductory thoughts: These areas of practice in yoga are really all part of the same, with Tantra being the historical development in practice that later spawned hatha yoga. Practices originating in these traditions form much of what we practice in the modern day yoga. Many terms, ideas and theories that we use come from this body of knowledge though we may not always fully realise it or understand or appreciate their original context and intent. There are a huge number of practices described that may or may not seem relevant to our current practice and interests. These practices are ultimately designed for complete transformation and liberation, but along the way there are many practices designed to be of therapeutic value to humans on many levels and without which the potential for transformation cannot happen. Historically, Tantra started to emerge around the 6th to 8th Centuries A.D. partly as a response to unrealistic austerities in yoga practice that some practitioners were espousing in relation to lifestyle, food, sex and normal householder life in general. Tantra is essentially a re-embracing of all aspects of life as being part of a yogic path; the argument being that if indeed all of life manifests from an underlying source and is therefore all interconnected then all of life is inherently spiritual or worthy of our attention. And indeed, if we do not attend to all aspects of life in our practice this can lead to problems and imbalances. This embracing of all of life includes looking at our shadows and dark sides and integrating or transforming them, ideas which also seem to be embraced in modern psychology. -

Ultimate Guide to Yoga for Healing

HEAD & NECK ULTIMATE GUIDE TO YOGA FOR HEALING Hands and Wrists Head and Neck Digestion Shoulders and Irritable Bowel Hips & Pelvis Back Pain Feet and Knee Pain Ankles Page #1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Click on any of the icons throughout this guide to jump to the associated section. Head and Neck .................................................Page 3 Shoulders ......................................................... Page 20 Hands and Wrists .......................................... Page 30 Digestion and IBS ......................................... Page 39 Hips ..................................................................... Page 48 Back Pain ........................................................ Page 58 Knees ................................................................. Page 66 Feet .................................................................... Page 76 Page #2 HEAD & NECK Resolving Neck Tension DOUG KELLER Pulling ourselves up by our “neckstraps” is an unconscious, painful habit. The solution is surprisingly simple. When we carry ourselves with the head thrust forward, we create neck pain, shoul- der tension, even disc herniation and lower back problems. A reliable cue to re- mind ourselves how to shift the head back into a more stress-free position would do wonders for resolving these problems, but first we have to know what we’re up against. When it comes to keeping our head in the right place, posturally speaking, the neck is at something of a disadvantage. There are a number of forces at work that can easily pull the neck into misalignment, but only a few forces that maintain the delicate alignment of the head on the spine, allowing all the supporting muscles to work in harmony. Page #3 HEAD & NECK The problem begins with the large muscles that converge at the back of the neck and attach to the base of the skull. These include the muscles of the spine as well as those running from the top of the breastbone along the sides of the neck (the sternocleidomastoids) to the base of the head. -

Notes and Topics: Three Divine Bodies: Tri-Kaya

TIlREE DIVINE BODIES: TRI-KAYA -Prof. P.G.yogi. The universal essence manifests itself in three aspects or modes as symbolized by the three Divine Bodies (Sanskrit-Trikaya). The first aspect, the Dharmakaya or the Essential (or True) Body is the primordial, unmodified, formless, eternally self existing and essentially of Bodhi or divine beingness. The second aspect is the Sambhogakaya or the Reflected Body wherein dweU the Buddhas of meditation (Skt. Dhyana-Buddhas) and other enlightened beings of super human form The third aspect is the Nirmanakaya or the Body of Incarnation or the human form in which state Buddha was born on earth. In the chinese interpretation of the Tri-kaya, the Dharmakaya is the immutable Buddha essence and noumenal source of the cosmic whole. The Sambhogakaya is the phe nomenal appearances and the first reflex of the Dharmakaya on the heavenly planes. In the Nirmanakaya, the Buddha essence is associated with activity on the Earth plane and it incarnates among men as suggested by the Gnostic poem in the Gospel of St.John which refers to the cOming of the word and the mind through human body. See herein book II, p. 217). In its totality, the universal essence is the one mind, manjfested through the myriads of minds in all the states of Sangsaric existence. It is called 'the essence of the Buddha', 'the great symbol', 'the sole seed' 'the potentiality of truth', and 'the all-foundation' as the text states that it is the source of all the bliss of Nirvana and all the sorrow of Sangsara. -

JONATHAN EDELMANN University of Florida • Department of Religion

JONATHAN EDELMANN ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGION University of Florida • Department of Religion 107 Anderson Hall • Room 106 • Gainesville FL 32611 (352) 273-2932 • [email protected] EDUCATION PH.D. | 2008 | UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD | RELIGIOUS STUDIES AND THEOLOGY Dissertation When Two Worldviews Meet: A Dialogue Between the Bhāgavata Purāṇa & Contemporary Biology Supervisors Prof. John Hedley Brooke, Oxford University Prof. Francis Clooney, Harvard University M.ST. | 2003 | UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD | SCIENCE AND RELIGION Thesis The Value of Science: Perspectives of Philosophers of Science, Stephen Jay Gould and the Bhāgavata-Purāṇa’s Sāṁkhya B.A. | 2002 | UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA–SANTA BARBARA | PHILOSOPHY Graduated with honors, top 2.5% of class POSITIONS ! 2015-present, Assistant Professor of Religion, Department of Religion, University of Florida ! 2012-present, Section Editor for Hindu Theology, International Journal of Hindu Studies ! 2014-present, Consulting Editor, Journal of the American Philosophical Association ! 2013-2015, Honors College Faculty Fellow, Mississippi State University ! 2010-2012, American Academy of Religion, Luce Fellow in Comparative Theology and Theologies of Religious Pluralism ! 2009-2015, Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy & Religion, MSU ! 2008-2009, Post Doctoral Fellow, Harris Manchester College, Oxford University ! 2007-2008, Religious Studies Teacher, St Catherine’s School, Bramley, UK RECENT AWARDS ! 2016, Humanities Scholarship Enhancement Fund Committee, College of Liberal Arts and -

Karma Yoga, Its Origins, Fundamentals and Seven Life Constructs

International Journal of Hinduism & Philosophy (IJHP) November 2019 Karma yoga, its origins, fundamentals and seven life constructs Dr. Palto Datta Centre for Business & Economic Research (CBER), UK Mark T Jones Centre for Innovative Leadership Navigation (CILN), UK Karma yoga is both simple and complex at the same time and as such requires a measured and reflective response. This paper in exploring the origins and fundamentals of karma yoga has sought to present interpretations in a clear and sattvic manner, synthesising key elements into seven life constructs. Karma yoga is revealed to have an eternal relevance, one that benefits from intimate knowledge of the Bhagavad Gita. By drawing on respected texts and commentaries it has striven to elucidate certain sacred teachings and give them meaning so that they become a guide for daily living. Keywords Purpose The purpose of this study is to gain an understanding of the concept of Karma yoga and its Altruism, place in the Bhagavad Gita and how this philosophical thought can influence people’s Bhagavad Gita, conduct and mindset. The study focuses on identifying the various dimensions of karma Karma yoga, yoga, with special reference to Niskarma yoga and the life constructs drawn from it. Karma yogi, Design/methodology Niskama Karma The study has employed a qualitative research methodology. To achieve the study objectives, yoga, and identify the various constructs of the Niskama Karma yoga, the study used content Service analysis of three main texts authored by Swami Vivekananda, Mohandas Karamchand conscious ness Gandhi, Swami Chinmayananda as a source of reference and extensive literature review on various scholarly journal articles and relevant books that discussed extensively the concept of Karma Yoga, Niskarma Yoga and relevant key areas of the study. -

Jain Philosophy and Practice I 1

PANCHA PARAMESTHI Chapter 01 - Pancha Paramesthi Namo Arihantänam: I bow down to Arihanta, Namo Siddhänam: I bow down to Siddha, Namo Äyariyänam: I bow down to Ächärya, Namo Uvajjhäyänam: I bow down to Upädhyäy, Namo Loe Savva-Sähunam: I bow down to Sädhu and Sädhvi. Eso Pancha Namokkäro: These five fold reverence (bowings downs), Savva-Pävappanäsano: Destroy all the sins, Manglänancha Savvesim: Amongst all that is auspicious, Padhamam Havai Mangalam: This Navakär Mantra is the foremost. The Navakär Mantra is the most important mantra in Jainism and can be recited at any time. While reciting the Navakär Mantra, we bow down to Arihanta (souls who have reached the state of non-attachment towards worldly matters), Siddhas (liberated souls), Ächäryas (heads of Sädhus and Sädhvis), Upädhyäys (those who teach scriptures and Jain principles to the followers), and all (Sädhus and Sädhvis (monks and nuns, who have voluntarily given up social, economical and family relationships). Together, they are called Pancha Paramesthi (The five supreme spiritual people). In this Mantra we worship their virtues rather than worshipping any one particular entity; therefore, the Mantra is not named after Lord Mahävir, Lord Pärshva- Näth or Ädi-Näth, etc. When we recite Navakär Mantra, it also reminds us that, we need to be like them. This mantra is also called Namaskär or Namokär Mantra because in this Mantra we offer Namaskär (bowing down) to these five supreme group beings. Recitation of the Navakär Mantra creates positive vibrations around us, and repels negative ones. The Navakär Mantra contains the foremost message of Jainism. The message is very clear. -

Dhyana in Hinduism

Dhyana in Hinduism Dhyana (IAST: Dhyāna) in Hinduism means contemplation and meditation.[1] Dhyana is taken up in Yoga exercises, and is a means to samadhi and self- knowledge.[2] The various concepts of dhyana and its practice originated in the Vedic era of Hinduism, and the practice has been influential within the diverse traditions of Hinduism.[3][4] It is, in Hinduism, a part of a self-directed awareness and unifying Yoga process by which the yogi realizes Self (Atman, soul), one's relationship with other living beings, and Ultimate Reality.[3][5][6] Dhyana is also found in other Indian religions such as Buddhism and Jainism. These developed along with dhyana in Hinduism, partly independently, partly influencing each other.[1] The term Dhyana appears in Aranyaka and Brahmana layers of the Vedas but with unclear meaning, while in the early Upanishads it appears in the sense of "contemplation, meditation" and an important part of self-knowledge process.[3][7] It is described in numerous Upanishads of Hinduism,[8] and in Patanjali's Yogasutras - a key text of the Yoga school of Hindu philosophy.[9][10] A statue of a meditating man (Jammu and Kashmir, India). Contents Etymology and meaning Origins Discussion in Hindu texts Vedas and Upanishads Brahma Sutras Dharma Sutras Bhagavad Gita The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali Dharana Dhyana Samadhi Samyama Samapattih Comparison of Dhyana in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism Related concept: Upasana See also Notes References Sources Published sources Web-sources Further reading External links Etymology