Policy Deliberation and Electoral Returns: Experimental Evidence from Benin and the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONSOLIDATED LIST of LPG ESTABLISHMENTS with SCC As of June 30, 2020

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF LPG ESTABLISHMENTS WITH SCC As of June 30, 2020 REGION PROVINCE CITY/MUNICIPALITY ACTIVITY BUSINESS NAME SCC ISSUANCE CODE DATE ISSUED DATE OF EXPIRY 1 4 Batangas Balayan LPG RP Brenton International Ventures Manufacturing Corp (for. Balayan)OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) 055-2017-09-004Brenton 06-Sep-17 06-Sep-20 2 4 Batangas Batangas City LPG RP C & J Gaz Refilling Station OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) -22-13-2019-8-1C&J 23-Aug-19 23-Aug-22 3 4 Batangas Bauan LPG RP Southern Gas Corporation OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) -4-9-2018-6-1Southern 13-Jun-18 13-Jun-21 4 4 Batangas Calaca LPG RP Republic Gas Corporation OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) 046-2017-06-002Republic 19-Jun-17 19-Jun-20 5 4 Batangas Rosario LPG RP Republic Gas Corporation OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) 063-2017-12-005Republic 06-Dec-17 06-Dec-20 6 4 Batangas San Jose LPG RP Oro Oxygen Corporation OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P)-35-26-2019-12-5Oro 20-Dec-19 20-Dec-22 7 4 Batangas Sto. Tomas LPG RP Eco Savers Gas Corporation OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) 061-2017-09-001Eco 27-Sep-17 27-Sep-20 8 4 Batangas Sto. Tomas LPG RP Mabuhay V Gas Corporation OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) 002-2018-02-001Mabuhay 02-Feb-18 02-Feb-21 9 4 Batangas Sto. Tomas LPG RP Royal Gas Corporation OIMB-CO-SCC(R/P) 050-2017-07-001Royal 13-Jul-17 13-Jul-20 10 4 Batangas Tuy LPG RP Pryce Gases, Inc. -

Ncr Region Iii Region Iva Region Iii Region

121°0'0"E 122°E 123°E Typhoon Santi has affected over 54,630 people MALOLOS 108 across 264 barangays in 15 cities / 66 municipalities REGION III of 14 provinces of Region III, IVA, IVB, V and NCR. OBANDO DILASAG Over 19,356 persons are currently housed in 103 70 170 Philippines: Typhoon evacuation centres. Reportedly, 16 people were "Santi" - Affected killed and many more injured. Population VALENZUELA 254 Around 115,507 people were pre-emptively PILAR (as of 0600H, 02 Nov 2009, NAVOTAS QUEZON CITY 25 evacuated across 251 evacuation centres while NDCC Sit Rep 09) 440 1230 others stayed with their relatives/friends in Regions NCR NCR, IV-A and V. 16°N Map shows the number of affected persons, 16°N ORION CAINTA by City or Municipality, as of 02 Nov 2009 414 \! 1572 0600hr, assessed by NDCC (in "Santi" Sit Rep MANDALUYONG REGION III Legend 09). The map focuses on the area affected by MANILA 685 typhoon "Santi". 3520 PASIG BALER \! Capital 1195 TAYTAY PATEROS 12 ´ Map Doc Name: 102 275 MA088-PHL-SANTI-AftPop-2Nov2009-0600-A3- Manila Bay PASAY Provincial Boundary v01-graphicsconverted 165 ANGONO TAGUIG 495 Municipal Boundary GLIDE Number: TC-2009-000230-PHL 14°30'0"N CAVITE CITY 405 14°30'0"N 3460 Regional Boundary Creation Date: 01 November 2009 Projection/Datum: UTM/Luzon Datum NOVELETA LAS PIÑAS 130 368 BACOOR Affected Population Web Resources: http://www.un.org.ph/response/ ROSARIO 650 230 DINGALAN by City/Municipality IMUS MUNTINLUPA Nominal Scale at A3 paper size 380 1725 20 0-170 Data sources: GENERAL TRIAS 171-495 40 - (www.nscb.gov.ph). -

Region IV CALABARZON

Aurora Primary Dr. Norma Palmero Aurora Memorial Hospital Baler Medical Director Dr. Arceli Bayubay Casiguran District Hospital Bgy. Marikit, Casiguran Medical Director 25 beds Ma. Aurora Community Dr. Luisito Te Hospital Bgy. Ma. Aurora Medical Director 15 beds Batangas Primary Dr. Rosalinda S. Manalo Assumpta Medical Hospital A. Bonifacio St., Taal, Batangas Medical Director 12 beds Apacible St., Brgy. II, Calatagan, Batangas Dr. Merle Alonzo Calatagan Medicare Hospital (043) 411-1331 Medical Director 15 beds Dr. Cecilia L.Cayetano Cayetano Medical Clinic Ibaan, 4230 Batangas Medical Director 16 beds Brgy 10, Apacible St., Diane's Maternity And Lying-In Batangas City Ms. Yolanda G. Quiratman Hospital (043) 723-1785 Medical Director 3 beds 7 Galo Reyes St., Lipa City, Mr. Felizardo M. Kison Jr. Dr. Kison's Clinic Batangas Medical Director 10 beds 24 Int. C.M. Recto Avenue, Lipa City, Batangas Mr. Edgardo P. Mendoza Holy Family Medical Clinic (043) 756-2416 Medical Director 15 beds Dr. Venus P. de Grano Laurel Municipal Hospital Brgy. Ticub, Laurel, Batangas Medical Director 10 beds Ilustre Ave., Lemery, Batangas Dr. Evelita M. Macababad Little Angels Medical Hospital (043) 411-1282 Medical Director 20 beds Dr. Dennis J. Buenafe Lobo Municipal Hospital Fabrica, Lobo, Batangas Medical Director 10 beds P. Rinoza St., Nasugbu Doctors General Nasugbu, Batangas Ms. Marilous Sara Ilagan Hospital, Inc. (043) 931-1035 Medical Director 15 beds J. Pastor St., Ibaan, Batangas Dr. Ma. Cecille C. Angelia Queen Mary Hospital (043) 311-2082 Medical Director 10 beds Saint Nicholas Doctors Ms. Rosemarie Marcos Hospital Abelo, San Nicholas, Batangas Medical Director 15 beds Dr. -

One Big File

MISSING TARGETS An alternative MDG midterm report NOVEMBER 2007 Missing Targets: An Alternative MDG Midterm Report Social Watch Philippines 2007 Report Copyright 2007 ISSN: 1656-9490 2007 Report Team Isagani R. Serrano, Editor Rene R. Raya, Co-editor Janet R. Carandang, Coordinator Maria Luz R. Anigan, Research Associate Nadja B. Ginete, Research Assistant Rebecca S. Gaddi, Gender Specialist Paul Escober, Data Analyst Joann M. Divinagracia, Data Analyst Lourdes Fernandez, Copy Editor Nanie Gonzales, Lay-out Artist Benjo Laygo, Cover Design Contributors Isagani R. Serrano Ma. Victoria R. Raquiza Rene R. Raya Merci L. Fabros Jonathan D. Ronquillo Rachel O. Morala Jessica Dator-Bercilla Victoria Tauli Corpuz Eduardo Gonzalez Shubert L. Ciencia Magdalena C. Monge Dante O. Bismonte Emilio Paz Roy Layoza Gay D. Defiesta Joseph Gloria This book was made possible with full support of Oxfam Novib. Printed in the Philippines CO N T EN T S Key to Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. iv Foreword.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... vii The MDGs and Social Watch -

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT of LABOR and EMPLOYMENT National Wages and Productivity Commission Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board No

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT National Wages and Productivity Commission Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board No. IV-A City of Calamba, Laguna WAGE ORDER NO. IVA-11 SETTING THE MINIMUM WAGE FOR CALABARZON AREA WHEREAS, under R. A. 6727, Regional Tripartite Wages and Productivity Board –IVA (RTWPB- IVA) is mandated to rationalize minimum wage fixing in the Region considering the prevailing socio-economic condition affecting the cost of living of wage earners, the generation of new jobs and preservation of existing employment, the capacity to pay and sustainable viability and competitiveness of business and industry, and the interest of both labor and management; WHEREAS, the Board issues this Wage Order No. IVA-11, granting wage increases to all covered private sector workers in the Region effective fifteen (15) days upon publication in a newspaper of general circulation; WHEREAS, on 19 May 2006, the Trade Union Congress of the Philippines filed a petition for a Seventy Five Pesos (Php75.00) per day, across-the-board, and region wide wage increase; WHEREAS, the Board, in its intention to elicit sectoral positions on the wage issue, conducted region wide, separate consultations with Labor and Management Sectors on 20 and 22 June 2006, respectively, and a public hearing with Tripartite Sectors on 30 June 2006, in Calamba, Laguna; WHEREAS, the frequent and unpredictable increases in the price of petroleum products especially triggered by the Middle East crises would result to higher production -

Uimersity Mcrofihns International

Uimersity Mcrofihns International 1.0 |:B litt 131 2.2 l.l A 1.25 1.4 1.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS STANDARD REFERENCE MATERIAL 1010a (ANSI and ISO TEST CHART No. 2) University Microfilms Inc. 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages In any manuscript may have Indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques Is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When It Is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to Indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to Indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right In equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page Is also filmed as one exposure and Is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or In black and white paper format. * 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro fiche but lack clarify on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, all photographs are available In black and white standard 35mm slide format.* *For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertations Customer Services Department. -

Quezon I DEO Annual Procurement Plan for FY 2019

DPWH - Quezon I DEO Annual Procurement Plan for FY 2019 Source of Schedule for Each Procurement Activity Estimated Budget (PhP) Remarks PMO/ Mode of Funds Code (PAP) Procurement Program/Project (brief description of End-User Procurement Ads/Post of Contract Sub/Open of Bids Notice of Award Program/Project) IB/REI Signing Total MOOE CO/ABC GAA - FY 2019 Rehabilitation/Reconstruction/Upgrading of Damage Paved along Famy- DPWH - Quezon DPWH Regular Rehabilitation/Reconstruction of 19-DK-0001 Public Bidding 20-Sep-18 11-Oct-18 June 24,2019 25-Jun-19 26,445,000.00 528,900.00 25,916,100.00 Real-Infanta Dinahican Port Road, K0116 + 528 - K0117 + 227 I DEO Infrastructure Damage Paved Program GAA - FY 2019 Rehabilitation/Reconstruction/Upgrading of Damage Paved along Famy- DPWH - Quezon DPWH Regular Rehabilitation/Reconstruction of 19-DK-0002 Public Bidding 20-Sep-18 11-Oct-18 June 24,2019 25-Jun-19 40,000,000.00 800,000.00 39,200,000.00 Real-Infanta Dinahican Port Road, K0132 +400-K0133+605 I DEO Infrastructure Damage Paved Program GAA - FY 2019 Network Development Road Widening along MSR Diversion Road, DPWH - Quezon DPWH Regular 19-DK-0003 Public Bidding 18-Oct-18 08-Nov-18 July 18,2019 22-Jul-19 69,949,000.00 2,448,215.00 67,500,785.00 Road Widening K0125+(-350) - K0126+000 I DEO Infrastructure Program GAA - FY 2019 Road Widening along Lucena-Tayabas-Lucban-Sampaloc-Mauban Port DPWH - Quezon DPWH Regular 19-DK-0004 Public Bidding 20-Sep-18 11-Oct-18 June 24,2019 25-Jun-19 22,332,000.00 446,640.00 21,885,360.00 Road Widening Road K0128+(-340)-K0128+088 -

Pagsanjan Sub-Basin

TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 13. Pagsanjan Sub-basin ........................................................................................... 3 Geographic Location .............................................................................................................. 3 Political and Administrative Boundary ..................................................................................... 4 Land Cover ............................................................................................................................. 6 Watershed Characterization and Properties ........................................................................... 7 Drainage Network ............................................................................................................... 7 Sub-sub basin Properties .................................................................................................... 9 Water Quantity ......................................................................................................................10 Stream Flow ......................................................................................................................10 Water Balance ...................................................................................................................11 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 13-1 Geographical Map ..................................................................................................................... 3 Figure 13-2 Political Jurisdiction Map .......................................................................................................... -

2018 Annual Report

D R A F T Table of Contents Acknowledgement LLDA Vision, Mission, Core Values, Quality Policy The General Manager’s Report I. POLICY PLANNING SERVICES 7 APPROVAL OF THE FOLLOWING BOARD RESOLUTIONS: Board Resolution No. 539, Series of 2018 Board Resolution No. 540, Series of 2018 8 Board Resolution No. 542, Series of 2018 Board Resolution No. 545, Series of 2018 Ratification of Moa With Solar Philippines Board Ratification of MOA Between LLDA and University of The Philippines - Diliman For The Implementation of The Meco- Teco Multi-Platform and Cross-Sensor Water Quality Monitoring Report Memoandum of Agreement Between LLDA and The Research Institute For Tropical Medicine (RITM) For The Establishment and Implementation of Environmental Surveillance In The Philippines 9 Board Resolution No. 552, Series of 2018 Board Resolution No. 553, Series of 2018 Board Resolution No. 554, Series of 2018 Board Resolution No. 555, Series of 2018 10 CORPORATE PLANNING PARTNERSHIP AND COLLABORATION 11 DA Secretary Piñol Together with GM Joey Meets with The Hungarian Water Technology Corporation (HWTC) to address Issue on Pollution and Wastewater Treatment in Laguna Lake. 12 “Opensa Kontra Kakulangan Sa Edukasyon (OKKE)” In Partnership with Local Government Unit of Sta. Maria, Laguna and DepE 13 COMMUNICATION, EDUCATION AND PUBLIC AWARENESS LLDA-LGU Summit: “Strengthening Partnerships For Good Environmental Governance” 14 Climate-Smart Land Use Planning For Sustainable and Resilient Laguna De Bay Basin Forum Stakeholders’ Assembly: Sama-Samang Hakbangin Tubig Kanlungan Kalingain 15 Series of Public Consultations on The 2018 Fishery Zoning and Management Guidelines (ZOMAG) of Laguna De Bay 16 International Coastal Clean-Up 2018 17 Customer Satisfaction Survey 18 Water Quality Monitoring Program 20 Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) 22 Dissolved Oxygen (DO) Ammonia Phosphate Fecal Coliform 23 Lake Primary Productivity CONSOLIDATED HYDROMETEOROLOGICAL DATA 24 Rainfall D R A F T 25 Lake Level 26 Laguna De Bay Water Balance II. -

Spes Beneficiary Area 1 Aaron Andal Cabuyao, Laguna 2

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT REGION IV-A LIST OF SPES BENEFICIARIES - LAGUNA 2013 SPES BENEFICIARY AREA 1 AARON ANDAL CABUYAO, LAGUNA 2 AARON JOSEPH CAÑA SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA 3 AARON PAUL DON SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA 4 AARON PAUL PUNONGBAYAN CABUYAO, LAGUNA 5 ABEGAIL MAHUSAY BIÑAN, LAGUNA 6 ABIGAEL TANAEL BIÑAN, LAGUNA 7 ABIGAIL CAPACITE SAN PEDRO, LAGUNA 8 ABIGAIL CAPARDO SAN PEDRO, LAGUNA 9 ABIGAIL DOMINGO ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 10 ABIGAIL FLORES PANGIL, LAGUNA 11 ACE ALEXIS AGUTOS STA. CRUZ, LAGUNA 12 ACE JOVELLAND NAGCARLAN, LAGUNA 13 ADELICA MARIEN IGNACIO PANGIL, LAGUNA 14 ADRIAN CASTILLO ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 15 ADRIAN DANIEL ERA BIÑAN, LAGUNA 16 ADRIAN LENDIO CALAMBA, LAGUNA 17 ADRIAN NEIL REYES CALAMBA, LAGUNA 18 ADRIANE DAVE TEVES CALAMBA, LAGUNA 19 AERHAN APACIONADO LUMBAN, LAGUNA 20 AHRJAY TRINIDAD CALAMBA, LAGUNA 21 AIKA JAMILLE OMIYA CALAMBA, LAGUNA 22 AILEEN DALUYEN VICTORIA, LAGUNA 23 AILEEN DOMOGMA SAN PEDRO, LAGUNA 24 AILEEN JOVY GUIEB SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA 25 AILEEN UMANDAP CALAMBA, LAGUNA 26 AILEN MAY MARIE REY CALAMBA, LAGUNA 27 AILENE TUBIG VICTORIA, LAGUNA 28 AIMEE FHER MANGLO CALAMBA, LAGUNA 29 AIRA ANTONETTE PAVIA SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA 30 AIRA JOY GEJIS CALAMBA, LAGUNA 31 AIRA MAE CABRERA CALAMBA, LAGUNA 32 AIRA NATNAT LUISIANA, LAGUNA 33 AIZEL JHANE URRIZA NAGCARLAN, LAGUNA 34 AIZEL JUSTINE CORPUZ PANGIL, LAGUNA 35 AIZON DIOMAMPO CALAMBA, LAGUNA 36 AJAH MARIANO PILA, LAGUNA 37 ALAINA GIEZEL BASUAN SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA 38 ALAIZZA BIENGRACE FLORES PILA, LAGUNA 39 ALBERT ADVENTO PAETE, LAGUNA 40 ALDINE BARTOLAZO SANTA ROSA, LAGUNA 41 ALDRIN AWOG LILIW, LAGUNA 42 ALDRIN ERISPE BIÑAN, LAGUNA 43 ALDRIN MATABUENA SAN PEDRO, LAGUNA 44 ALEJN ELLICE PANTALEON SINILOAN, LAGUNA 45 ALELIE GONZAGA CALAMBA, LAGUNA 46 ALERRY LAYOG CALAMBA, LAGUNA 47 ALEXA MARIZ PISANO NAGCARLAN, LAGUNA 48 ALEXANDER FERDINAND HERNAN SAN PEDRO, LAGUNA 49 ALEXANDER OCHINANG, JR. -

Biological Control: a Major Component of the Pest Management Program for the Invasive Coconut Scale Insect, Aspidiotus Rigidus Reyne, in the Philippines

insects Article Biological Control: A Major Component of the Pest Management Program for the Invasive Coconut Scale Insect, Aspidiotus rigidus Reyne, in the Philippines Billy Joel M. Almarinez 1,2 , Alberto T. Barrion 1,2, Mario V. Navasero 3 , Marcela M. Navasero 3, Bonifacio F. Cayabyab 3, Jose Santos R. Carandang VI 1,2, Jesusa C. Legaspi 4, Kozo Watanabe 5 and Divina M. Amalin 1,2,* 1 Biology Department, College of Science, De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila 1004, Philippines; [email protected] (B.J.M.A.); [email protected] (A.T.B.); [email protected] (J.S.R.C.VI) 2 Biological Control Research Unit, Center for Natural Science and Environmental Research, De La Salle University, Taft Avenue, Manila 1004, Philippines 3 National Crop Protection Center, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Los Baños, Laguna 4031, Philippines; [email protected] (M.V.N.); [email protected] (M.M.N.); [email protected] (B.F.C.) 4 Center for Medical, Agricultural and Veterinary Entomology, United States Department of Agriculture—Agricultural Research Service, Tallahassee, FL 32308, USA; [email protected] 5 Center for Marine Environmental Studies, Ehime University, Matsuyama, Ehime 790-8577, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 August 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 30 October 2020 Simple Summary: Major outbreaks of the coconut scale insect (CSI), Aspidiotus rigidus, occurred in the Philippines, between 2010 and 2016 in the Southern Tagalog region of Luzon Island, and from 2017 to 2020 in the Zamboanga Peninsula, Mindanao Island. -

Er Doe Website Final

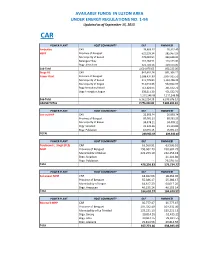

AVAILABLE FUNDS IN LUZON AREA UNDER ENERGY REGULATIONS NO. 1-94 Updated as of September 15, 2013 CAR POWER PLANT HOST COMMUNITY DLF RWMHEEF Ambuklao CAR 76,666.97 95,322.40 HEPP Province of Benguet 622,239.34 285,967.19 Municipality of Bokod 478,082.54 333,628.39 Barangay Tikey 116,184.51 119,153.00 Brgy. Ambuklao 321,703.26 119,153.00 Sub-Total 1,614,876.62 953,223.98 Binga HE CAR 847,493.24 801,306.17 Power Plant Province of Benguet 2,188,437.90 1,907,925.51 Municipality of Bokod 341,779.85 1,153,406.40 Municipality of Itogon 514,018.86 502,824.03 Brgy.Ambuklao,Bokod 713,424.05 301,632.71 Brgy.Tinongdan,Itogon 338,811.30 451,632.71 1,217,248.98 1,217,248.98 Sub-Total 6,161,214.18 6,335,976.51 GRAND TOTAL 7,776,090.80 7,289,200.49 POWER PLANT HOST COMMUNITY DLF RWMHEEF Lon-oy MHP CAR 26,993.74 26,993.74 Province of Benguet 80,981.23 80,981.23 Municipality of Bakun 94,478.11 94,478.11 Brgy. Sinacbat 21,421.46 21,101.80 Brgy. Poblacion 16,091.15 16,091.15 TOTAL 239,965.69 239,646.03 POWER PLANT HOST COMMUNITY DLF RWMHEEF Ferdinand L. Singit (FLS) CAR 63,500.91 63,500.91 MHP Province of Benguet 190,502.73 190,502.73 Municipality of Bakun 222,253.19 222,253.19 Brgy. Sinacbat - 21,101.80 Brgy.