THE NEW POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY of EUROPE Edited by Nicholas Walton and Jan Zielonka ABOUT ECFR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EUU Alm.Del Offentligt Referat Offentligt

Europaudvalget 2011-12 EUU Alm.del Offentligt referat Offentligt Europaudvalget REFERAT AF 30. EUROPAUDVALGSMØDE Dato: Torsdag den 3. maj 2012 Tidspunkt: Kl. 10.30 Sted: Vær. 2-133 Til stede: Jens Joel (S), Rasmus Helveg Petersen (RV), Nikolaj Villumsen (EL), Finn Sørensen (EL), Lykke Friis (V), Jakob Ellemann-Jensen (V), Pia Adelsteen (DF) fungerende formand, Merete Riisager (LA), Lene Espersen (KF) Desuden deltog: Børne- og undervisningsminister Christine Antorini, ud- viklingsminister Christian Friis Bach, europaminister Nico- lai Wammen og kulturminister Uffe Elbæk Pia Adelsteen ledede mødet FO Punkt 1. Rådsmøde nr. 3164 (uddannelse, ungdom, kultur og sport – uddannelses- og ungdomsdelen) den 10.-11. maj 2012 Under dette punkt på Europaudvalgets dagsorden forelagde børne- og under- visningsministeren punkt 1-4 på dagsordenen for rådsmødet. De øvrige punk- ter på rådsmødet blev forelagt af kulturministeren under punkt 4 på Euro- paudvalgets dagsorden. Undervisningsministeren: Det er jo ikke så tit, jeg har fornøjelsen af at komme her i Europaudvalget. Det er dejligt, at det sker som led i det danske formand- skab. Jeg vil i dag forelægge punkterne på rådsmødet for uddannelse og ungdom, der finder sted på næste fredag, den 11. maj 2012. Jeg forelægger én sag til forhandlingsoplæg. Det er det første punkt om Erasmus for Alle. De to øvrige sager forelægger jeg til orientering. Uddannelse FO 1. Europa-Parlamentets og Rådets forordning om oprettelse af Erasmus for Alle – EU-programmet for uddannelse, ungdom og idræt – Delvis generel indstilling KOM (2011) 0788 Rådsmøde 3164 – bilag 1 (samlenotat side 2) KOM (2011) 0788 – bilag 2 (grundnotat af 25/1-2012) 1093 30. Europaudvalgsmøde 3/5-12 Undervisningsministeren: Kommissionen fremsatte i november sidste år for- slag til et integreret EU-program for uddannelse, ungdom og idræt. -

74. Møde Ken Denne Eller Næste Valgperiode, Hvordan Har Man Så Tænkt Sig at Onsdag Den 14

Onsdag den 14. april 2010 (D) 1 6) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: Simon Emil Ammitzbøll (LA): Når regeringen ikke vil være med til at afskaffe efterlønnen i hver- 74. møde ken denne eller næste valgperiode, hvordan har man så tænkt sig at Onsdag den 14. april 2010 kl. 13.00 løse den demografiske og økonomiske udfordring? (Spm. nr. S 1806). Dagsorden 7) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: Simon Emil Ammitzbøll (LA): 1) Spørgsmål til ministrene til umiddelbar besvarelse (spørgeti- Mener ministeren, at det er mere værdigt at være på efterløn end på me). førtidspension? (Spm. nr. S 1807). 2) Besvarelse af oversendte spørgsmål til ministrene (spørgetid). (Se nedenfor). 8) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: Bjarne Laustsen (S): Hvordan vil ministeren sikre, at f.eks. en hustru, der har arbejdet i sin ægtefælles virksomhed, men er blevet opsagt og reelt fratrådt, 1) Til indenrigs- og sundhedsministeren af: som står til rådighed, er aktivt jobsøgende og har betalt sit kontin- Liselott Blixt (DF): gent, kan få understøttelse? Hvordan stiller ministeren sig til forslaget fra Kræftens Bekæmpelse, (Spm. nr. S 1822). der har foreslået, at det fremover skal være patienten selv og ikke den behandlende læge, der indstiller til second opinion? 9) Til beskæftigelsesministeren af: (Spm. nr. S 1820). Bjarne Laustsen (S): Hvorfor sikrer ministeren ikke, at jobcentrene stiller samme krav til, 2) Til indenrigs- og sundhedsministeren af: når de langt om længe har bevilget arbejdsløse en voksenlærlingeud- Liselott Blixt (DF): dannelse, for så vidt angår krav om jobsøgning, rådighed og betaling Hvad er ministerens holdning til, at Region Sjælland er en betragte- i skolepraktikperioden? lig mere »usund« region end de andre regioner, og bør der iværksæt- (Spm. -

Israel Today Maart 2017.1.1

Maart 2017 ISRAËL/NEDERLAND 37 www.israeltoday.nl Israëlische ambassadeur in Nederland: ’Terugkeer Joden versterkt de staat Israël’ Sjoukje Dijkstra Ambassadeur ‘Israël is het thuisland van alle Joden, Aviv Shir-On wereldwijd’, dat zegt Aviv Shir-On, de nieuwe tijdens de welkomstreceptie ambassadeur van Israël in Nederland. Dat die in veel Joden vandaag de dag terugkeren naar januari werd Israël ziet hij als een positieve ontwikkeling. georganiseerd door het ‘Het maakt de staat Israël sterk, en het ver- IsraëlPlatform. stevigt de positie van het volk.’ erder zegt de ambassadeur: ‘Het leiden om de situatie tussen de Israëli’s verspreiden van de waarheid ons helpen Vzal ons helpen om onze relatie met en de Palestijnen te verbeteren. In decem- om de relaties te verbeteren tussen de andere landen te verbeteren.’ Volgens ber vond er een eerste ontmoeting plaats mensen.’ Overheden schuift hij daarbij Shir-On is een sterk Israël belangrijk tussen premier Rutte en Netanyahu hier ter zijde. ‘Het gaat om het publiek, de voor Europa en de hele wereld: ‘In het in Den Haag. En er zal nog een vervolg mensen. Overheden hebben immers altijd bijzonder vanwege wat er er nu gebeurt op komen.’ bijbedoelingen en politieke belangen.’ in het Midden-Oosten. Hoe meer Joden De boodschap van er naar Israël komen, hoe sterker en Gemis gelukkiger Israël zal zijn.’ Aviv Shir-On Shir-On woont en werkt nog maar Het eerste doel van de nieuwe een half jaar in Nederland en mist Israël. Positieve ontwikkelingen ambassadeur is om de boodschap van de ‘Maar gelukkig zijn daar nog de moderne Shir-On liet daarbij weten hoop- staat Israël en het volk aan de mensen communicatie- en transportmiddelen. -

Great Expectations: the Experienced Credibility of Cabinet Ministers and Parliamentary Party Leaders

Great expectations: the experienced credibility of cabinet ministers and parliamentary party leaders Sabine van Zuydam [email protected] Concept, please do not cite Paper prepared for the NIG PUPOL international conference 2016, session 4: Session 4: The Political Life and Death of Leaders 1 In the relationship between politics and citizens, political leaders are essential. While parties and issues have not become superfluous, leaders are required to win support of citizens for their views and plans, both in elections and while in office. To be successful in this respect, credibility is a crucial asset. Research has shown that credible leaders are thought to be competent, trustworthy, and caring. What requires more attention is the meaning of competent, caring, and trustworthy leaders in the eyes of citizens. In this paper the question is needed to be credible according to citizens in different leadership positions, e.g. cabinet ministers and parliamentary party leaders. To answer this question, it was studied what is expected of leaders in terms of competence, trustworthiness, and caring by conducting an extensive qualitative analysis of Tweets and newspaper articles between August 2013 and June 2014. In this analysis, four Dutch leadership cases with a contrasting credibility rating were compared: two cabinet ministers (Frans Timmermans and Mark Rutte) and two parliamentary party leaders (Emile Roemer and Diederik Samsom). This analysis demonstrates that competence relates to knowledgeability, decisiveness and bravery, performance, and political strategy. Trustworthiness includes keeping promises, consistency in views and actions, honesty and sincerity, and dependability. Caring means having an eye for citizens’ needs and concern, morality, constructive attitude, and no self-enrichment. -

EUI RSCAS Working Paper 2020

RSCAS 2020/88 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/88 Terms of access and reuse for this work are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC- BY 4.0) International license. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper series and number, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Viktor Emil Sand Madsen, 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0) International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Published in December 2020 by the European University Institute. Badia Fiesolana, via dei Roccettini 9 I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual author(s) and not those of the European University Institute. This publication is available in Open Access in Cadmus, the EUI Research Repository: https://cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. -

And Others a Geographical Biblio

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 108 SO 001 480 AUTHOR Lewtbwaite, Gordon R.; And Others TITLE A Geographical Bibliography for hmerican College Libraries. A Revision of a Basic Geographical Library: A Selected and Annotated Book List for American Colleges. INSTITUTION Association of American Geographers, Washington, D.C. Commission on College Geography. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Commission on College Geography, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85281 (Paperback, $1.00) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 BC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, Booklists, College Libraries, *Geography, Hi7her Education, Instructional Materials, *Library Collections, Resource Materials ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography, revised from "A Basic Geographical Library", presents a list of books selected as a core for the geography collection of an American undergraduate college library. Entries numbering 1,760 are limited to published books and serials; individual articles, maps, and pamphlets have been omii_ted. Books of recent date in English are favored, although older books and books in foreign languages have been included where their subject or quality seemed needed. Contents of the bibliography are arranged into four principal parts: 1) General Aids and Sources; 2)History, Philosophy, and Methods; 3)Works Grouped by Topic; and, 4)Works Grouped by Region. Each part is subdivided into sections in this general order: Bibliographies, Serials, Atlases, General, Special Subjects, and Regions. Books are arranged alphabetically by author with some cross-listings given; items for the introductory level are designated. In the introduction, information on entry format and abbreviations is given; an index is appended. -

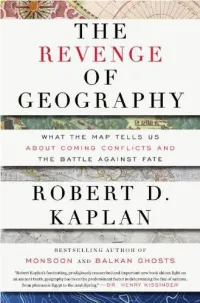

The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming

Copyright © 2012 by Robert D. Kaplan Maps copyright © 2012 by David Lindroth, Inc. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. The preface contains material from four earlier titles by Robert D. Kaplan: Soldiers of God (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 1990), An Empire Wilderness (New York: Random House, Inc., 1998), Eastward to Tartary (New York: Random House, Inc., 2000), and Hog Pilots, Blue Water Grunts (New York: Random House, Inc., 2007). LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Kaplan, Robert D. The revenge of geography : what the map tells us about coming conflicts and the battle against fate / by Robert D. Kaplan. p. cm. eISBN: 978-0-679-60483-9 1. Political geography. I. Title. JC319.K335 2012 320.1′2—dc23 2012000655 www.atrandom.com Title-spread image: © iStockphoto Jacket design: Greg Mollica Front-jacket illustrations (top to bottom): Gerardus Mercator, double hemisphere world map, 1587 (Bridgeman Art Library); Joan Blaeu, view of antique Thessaly, from the Atlas Maior, 1662 (Bridgeman Art Library); Robert Wilkinson, “A New and Correct Map v3.1_r1 But precisely because I expect little of the human condition, man’s periods of felicity, his partial progress, his efforts to begin over again and to continue, all seem to me like so many prodigies which nearly compensate for the monstrous mass of ills and defeats, of indifference and error. Catastrophe and ruin will come; disorder will triumph, but order will too, from time to time. -

GENERAL ELECTIONS in NETHERLANDS 12Th September 2012

GENERAL ELECTIONS IN NETHERLANDS 12th September 2012 European Elections monitor Victory for the pro-European parties in the General Elections in the Netherlands Corinne Deloy Translated by helen Levy The People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), the liberal party led by outgoing Prime Minister Mark Rutte came first in the general elections on 12th September in the Netherlands. The party won 26.5% of the vote, the highest score in its history and won 41 seats (+10 than in the previous elections that took place on 9th June 2010). “It is an Results exceptional victory because he is the leader of the biggest party in office. There are many European countries in which the leaders lost the elections as this crisis rages,” analyses Andre Krouwel, a political expert at the Free University of Amsterdam. The liberals took a slight lead over the Labour Party (PvdA) led by Diederik Samsom, which won 24.7% of the vote and 39 seats (+9). At first the electoral campaign, which focused on the crisis, turned to the advantage of the most radical opposition forces, and those most hostile to the European Union (Socialist Party and the Freedom Party). Over the last few days however the situation developed further and the pro-European forces recovered ground. Together the Liberals and Labour rallied 80 seats, i.e. an absolute majority in the States General, the lower chamber in the Dutch Parliament. The populist parties suffered a clear rebuttal. On Turnout was slightly less than that recorded in the the right the Freedom Party (PVV) won 10.1% of last general elections on 9th June 2010 the vote, taking 15 seats (-9). -

Onderzoek: Roemer Stapt Op

13 december 2017 Onderzoek: Roemer stapt op ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Over het EenVandaag Opiniepanel Het EenVandaag Opiniepanel bestaat uit ruim 50.000 mensen. Zij beantwoorden vragenlijsten op basis van een online onderzoek. De uitslag van de peilingen onder het EenVandaag Opiniepanel zijn na weging representatief voor zes variabelen, namelijk leeftijd, geslacht, opleiding, burgerlijke staat, spreiding over het land en politieke voorkeur gemeten naar de laatste Tweede Kamerverkiezingen. Panelleden krijgen ongeveer één keer per week een uitnodiging om aan een peiling mee te doen. Op de meeste onderzoeken respondeert 50 tot 60 procent van de panelleden. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Roemer stapt op 13 december 2017 Over het onderzoek Aan het onderzoek deden 18.109 leden van het EenVandaag Opiniepanel mee, waarvan 1102 SP-stemmers die bij de landelijke verkiezingen in maart op de partij gestemd hebben. Het onderzoek vond plaats op 13 december 2017. Na weging is het onderzoek representatief voor zes variabelen, namelijk leeftijd, geslacht, opleiding, burgerlijke staat, spreiding over het land en politieke voorkeur gemeten naar de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. 2 1. Samenvatting SP-kiezers gematigd positief over Marijnissen Lilian Marijnissen wordt door SP-kiezers gematigd positief ontvangen als nieuwe partijleider: 64 procent heeft vertrouwen in haar. Dat blijkt uit een gewogen peiling van EenVandaag onder 1100 kiezers die in maart op de SP stemden. Een kwart (26%) heeft weinig tot geen vertrouwen. Kiezers van de PvdA en GroenLinks lopen op dit moment nog niet warm voor haar, datzelfde geldt voor kiezers van de PVV. Driekwart (74%) van de ondervraagde SP-kiezers vindt dat Emile Roemer het goed gedaan heeft. Toch stelt bijna de helft (45%) dat het een goede zaak is dat hij nu opstapt. -

Human Geography of Europe and Russia I

Human Geography of Europe and Russia I. Mediterranean Europe-Region where ________________________________________________ Greece o Made up of political units called _________________________ o Athens developed the 1st ______________________________ o Persian Wars in 400s B.C. weakened the city-states o In 338 B.C. __________________________________________ conquered Greece and part of India, spreading Greek culture Italy o Roman Empire-Ruled entire peninsula by ______________________ and was a ______________ o The Crusades- Began in 1096 A.D. and was a __________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ o Renaissance- 14th to 16th Centuries and was a _________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ o Bubonic Plague (aka the ________________________) in 1347. Spain o Ruled by the Muslims for about 700 years. Roman _____________________________ and Muslim ____________________________ still exist today. II. Western Europe France and Germany were considered the 2 most dominant countries in Western Europe The Reformation- Started in _______________ by _________________________. It was a time when _______________________________________________________________________________________ The Rise of Nation-States o Feudalism o Nationalism French Revolution (1789)-Overthrew the king (Louis XVI) and created a _____________________________. World War I (1914-1918)-Allied Powers (France, Great Britain, Russia, -

Decl I Ch É S Van Pr Insje Sdag

Politiek taalgebruik Rond Prinsjesdag wordt er verbaal veel van politici verwacht. Meest Met stoom Wie gebruikt g e b r u i kt e de meeste clichés Stip(pen) clichés? Van commentaar voor- en kokend zien door debatdeskun- Met alle dige Donatello Piras. aan de 1 Mark Rutte (VVD) re s p e c t wa t e r 52 clichés in 62 debatten 1 horizon klip en klaar 2 „Sleets en ouderwets. Ik Alexander Pechtold (D66) zou andere synoniemen 71 clichés in 113 debatten g e b r u i ke n . ” 2 Boter bij Ve r t ro uwe n 3 Halbe Zijlstra (VVD) met alle respect gaat te paard, 37 clichés in 60 debatten „Vaak de introductie van een vreselijke drogreden de vis komt te voet of grote woorden.” De cl i ch é s van Pr insje sdag 4 Arie Slob (CU) 3 55 clichés in 137 debatten Wo o rd ke u z e Weinig politici schuwen het cliché, bij zijn manier van oppositie voeren: het kabinet mispartij, de PvdA, excuseert zich verhoudings- boter bij de vis afschilderen als een club die geen keuzes maakt. gewijs het vaakst dat iets niet „de schoonheids- „Een term die je in norma- maar verschil moet er zijn. Wie is de clichékeizer Andere grootverbruikers van het politieke cli- pr ijs”verdient . le gesprekken bijna nooit ché zijn Arie Slob (ChristenUnie) en Emile Roe- En de PVV? Die partij komt ook qua clichége- 5 g e b r u i kt . ” van het Binnenhof en wie blinkt uit in originaliteit? mer (SP). -

Det Offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018

Det offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018 Udgiver: Finansministeriet Redaktion: Digitaliseringsstyrelsen Opsætning og layout: Rosendahls a/s ISBN 978-87-93073-23-4 ISSN 2446-4589 Det offentlige Danmark 2018 Oversigt over indretningen af den offentlige sektor Om publikationen Den første statshåndbog i Danmark udkom på tysk i Oversigt over de enkelte regeringer siden 1848 1734. Fra 1801 udkom en dansk udgave med vekslende Frem til seneste grundlovsændring i 1953 er udelukkende udgivere. Fra 1918 til 1926 blev den udgivet af Kabinets- regeringscheferne nævnt. Fra 1953 er alle ministre nævnt sekretariatet og Indenrigsministeriet og derefter af Kabi- med partibetegnelser. netssekretariatet og Statsministeriet. Udgivelsen Hof & Stat udkom sidste gang i 2013 i fuld version. Det er siden besluttet, at der etableres en oversigt over indretningen Person- og realregister af den offentlige sektor ved nærværende publikation, Der er ikke udarbejdet et person- og realregister til som udkom første gang i 2017. Det offentlige Danmark denne publikation. Ønsker man at fremfnde en bestem indeholder således en opgørelse over centrale instituti- person eller institution, henvises der til søgefunktionen oner i den offentlige sektor i Danmark, samt hvem der (Ctrl + f). leder disse. Hofdelen af den tidligere Hof- og Statskalen- der varetages af Kabinetssekretariatet, som stiller infor- mationer om Kongehuset til rådighed på Kongehusets Redaktionen hjemmeside. Indholdet til publikationen er indsamlet i første halvår 2018. Myndighederne er blevet