Media-Government Relations During Musharraf, Zardari and Nawaz's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metaphorical Devices in Political Cartoons with Reference to Political Confrontation in Pakistan After Panama Leaks

Metaphorical Devices in Political cartoons with Reference to Political Confrontation in Pakistan after Panama Leaks Ayesha Ashfaq Savera Shami Sana Naveed Khan It has been assumed that metaphorical and symbolic contests are waged with metaphors, captions and signs in political cartoons that play a significant role in image construction of political actors, situations or events in political arena. This paper is an effort to explore the metaphorical devices in political cartoons related to the political confrontation in Pakistan between the ruling party Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) and opposition parties especially after Panama leaks. For this purpose, political cartoons sketched by three renowned political cartoonists on the basis of their belongings to the highest circulated mainstream English newspapers of Pakistan and their extensive professional experiences in their genre, were selectedfrom April 2016 to July 29, 2017 (Period of Panama trail). The cartoons were analyzed through the Barthes’s model of Semiotics. It was observed that metaphorical devices in political cartoons are one of the key weapons of cartoonists’ armory. These devices are used to attack on the candidates and contribute to the image and character building. It was found that all the selected political cartoonists used different forms of metaphors including situational metaphors and embodying metaphors. Not only the physical stature but also the debates and their activities were depicted metaphorically in the cartoons that create the scenario of comparison between the cartoons and their real political confrontation. It was examined that both forms of metaphors shed light on cartoonist’s perception and newspaper’s policy about political candidates, political parties and particular events. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

Unit 19. Panama Papers- Case of Tax Evasion by the Rich

GAUTAM SINGH UPSC STUDY MATERIAL – International Relation 0 7830294949 Unit 19. Panama Papers- Case of Tax Evasion by the Rich The Panama Papers are documents which were leaked from Mossack Fonseca, a Panama-based law firm offering legal and trust services. It is alleged that many of these documents show how wealthy individuals – including public officials – hide their money from public scrutiny. Panama Papers: What is it? It is a set of 11.5 million documents that were leaked from a Panama-based corporate service provider Mossack Fonseca. (Note: Panama is a Central American country). It is considered as the biggest leak in the history, even bigger than the WikiLeaks and the Snowden leaks. The documents contain detailed information (including those of shareholders and directors, and even passport information!) about more than 2.14 lakh offshore companies listed by the agency. It is alleged that the agency facilitated the rich and influential people to hide their wealth from public scrutiny, and thus evade taxation in their domestic domains. The alleged perpetrators vary from current government leaders to public officials to close associates of various heads of the governments etc. The leak consists of data created between 1970s and late 2015. The data primarily comprises e-mails, PDF files, photos, and excerpts of an internal Mossack Fonseca database, covering a period from the 1970s to 2016. The Panama Papers leak provides data on some 214,000 companies with a folder for each shell firm that contains e-mails, contracts, transcripts, and scanned documents. The leak comprised over 4.8 million emails, 3 million database format files, 2.2 million PDFs, 1.2 million images, 320 thousand text files, and 2242 files in other formats. -

Malta 2016 Human Rights Report

MALTA 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Malta is a constitutional republic and parliamentary democracy. The president is the head of state, appointed by a resolution of the unicameral parliament (House of Representatives. Parliament appointed a new president in 2014. The president names as prime minister the leader of the party winning a majority of seats in parliamentary elections. The 2013 general elections were deemed free and fair. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over security forces. Lengthy delays in the judicial system, inadequate government programs for integrating migrants, and alleged corruption at senior government levels compounded by a lack of government transparency were the most significant human rights problems. Other problems included violence against women, trafficking in persons, societal racial discrimination, forced labor, and substandard work conditions for irregular migrants. The government took steps to investigate, prosecute, and punish officials who committed violations, whether in security services or elsewhere in the government. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings There were no reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. b. Disappearance There were no reports of politically motivated disappearances. c. Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment The constitution and law prohibit such practices. MALTA 2 Prison and Detention Center Conditions While there were no significant reports regarding prison or detention center conditions that raised general human rights concerns, poor conditions in detention centers for certain irregular migrants persisted. Physical Conditions: On October 25, the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) released a report on its September 2015 visit to the country. -

Tender Document for Procurement of Books for Library

UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION LAHORE TENDER DOCUMENT FOR PROCUREMENT OF BOOKS FOR LIBRARY Issued to: ___________________ Tender No. UE/Tender/201 7 - 1 8 / 32 i Purchase Section, University of Education, Township, Lahore Table of Contents S# Description Page # 1 Invitation to the Bid 1 2 Instructions to the Bidders 1 Terms and Conditions of the Tender 3 3 Definitions 3 4 Tender Eligibility 3 5 Examination of the Tender Document 3 6 Amendment of the Tender Document 3 7 Tender Price 3 8 Validity Period of the Bid 4 9 Bid Security 4 10 Bid Preparation and Submission 4 11 Modification and withdrawal of the Tender 6 12 Bid Opening 6 13 Preliminary Examination 6 14 Determination of the Responsiveness of the Bid 7 15 Technical Evaluation Criteria 8 16 Financial Proposal Evaluation 8 17 Rejection and Acceptance of the Tender 8 18 Contacting the Procuring Agency 9 19 Announcement of Evaluation Report 9 20 Award of Contract 9 21 Letter of Acceptance (LOA) 9 22 Payment of Performance Guarantee (PG) 9 23 Refund of Bid Security (BS) 9 24 Issuance of Supply Order or Signing the Contract 9 25 Redressal of Grievances by the Procuring Agency 10 General Conditions of Supply Order /Contract 11 26 Delivery of Items 11 27 Liquidated Damages 11 28 Inspection and Tests 11 29 Release of Performance Guarantee (PG) 12 30 Contract Amendment 12 31 Termination for Default 12 32 Mechanism for Blacklisting 12 33 Force Majeure 12 34 Termination of Insolvency 13 35 Arbitration and Resolution of Disputes 13 36 Forfeiture of Performance Security 13 37 Payment 13 38 Warranty -

Pld 2017 Sc 70)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction) PRESENT: Mr. Justice Asif Saeed Khan Khosa Mr. Justice Ejaz Afzal Khan Mr. Justice Gulzar Ahmed Mr. Justice Sh. Azmat Saeed Mr. Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan Constitution Petition No. 29 of 2016 (Panama Papers Scandal) Imran Ahmad Khan Niazi Petitioner versus Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, Prime Minister of Pakistan / Member National Assembly, Prime Minister’s House, Islamabad and nine others Respondents For the petitioner: Syed Naeem Bokhari, ASC Mr. Sikandar Bashir Mohmad, ASC Mr. Fawad Hussain Ch., ASC Mr. Faisal Fareed Hussain, ASC Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR with the petitioner in person Assisted by: Mr. Yousaf Anjum, Advocate Mr. Kashif Siddiqui, Advocate Mr. Imad Khan, Advocate Mr. Akbar Hussain, Advocate Barrister Maleeka Bokhari, Advocate Ms. Iman Shahid, Advocate, For respondent No. 1: Mr. Makhdoom Ali Khan, Sr. ASC Mr. Khurram M. Hashmi, ASC Mr. Feisal Naqvi, ASC Assisted by: Mr. Saad Hashmi, Advocate Mr. Sarmad Hani, Advocate Mr. Mustafa Mirza, Advocate For the National Mr. Qamar Zaman Chaudhry, Accountability Bureau Chairman, National Accountability (respondent No. 2): Bureau in person Mr. Waqas Qadeer Dar, Prosecutor- Constitution Petition No. 29 of 2016, 2 Constitution Petition No. 30 of 2016 & Constitution Petition No. 03 of 2017 General Accountability Mr. Arshad Qayyum, Special Prosecutor Accountability Syed Ali Imran, Special Prosecutor Accountability Mr. Farid-ul-Hasan Ch., Special Prosecutor Accountability For the Federation of Mr. Ashtar Ausaf Ali, Attorney-General Pakistan for Pakistan (respondents No. 3 & Mr. Nayyar Abbas Rizvi, Additional 4): Attorney-General for Pakistan Mr. Gulfam Hameed, Deputy Solicitor, Ministry of Law & Justice Assisted by: Barrister Asad Rahim Khan Mr. -

Five Policemen, Private Security Guards Killed in Kulgam Attack

K K M M , - Y Y C C $(+#(&)'' )"!'!(($ &)"%'#*$+$(#$"'' ($"( +(&& %(' &%&'#($$(!!$& '"'#'$$&' "!+ &#'%#)'' nation, 7P sports, 9P world, 8P DAILY Price 2.00 Pages : 12 JAMMU TUESDAY | MAY 02 2017 | VOL. 32 | NO. 120 | REGD. NO. : JM/JK 118/15 /17 | E-mail : [email protected] | epaper.glimpsesoffuture.com 111"'$(+- -*!!/./, *( Five policemen, private security guards killed in Kulgam attack Pak forces behead two Indian security men after crossing LoC ,$)",2 Meanwhile, a bank official told that no bank official was Five policemen and two killed in the attack. He said CM strongly private security guards were that the security guards, who Monday killed when militants were killed in the attack was condemns killing opened fire upon a vehicle of working for a private security of police personnel, JK Bank in Pombai area in company. He added that van Kulgam district. The militants was coming back from DH bank officials also decamped with the serv- Pora towards Kulgam town ice rifles of the slain cops, po- after depositing cash in local lice said. The militants cam- bank branches there. The in- Chief Minister, ouflaged in forces uniform cident created chaos in the Mehbooba Mufti has stopped the cash van of JK village. All the shops and oth- strongly condemned the Bank and fired indiscrimi- er business establishments killing of five police per- nately upon the vehicle. were closed in the village fol- sonnel and two bank offi- Following the attack, mili- lowing the incident. cials of a cash van who tants decamped with their Meanwhile, JK Bank were killed today by un- services rifles, the police offi- Chairman and CEO Parvez ((/2 known assailants at cial said. -

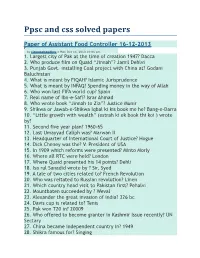

Ppsc and Css Solved Papers

Ppsc and css solved papers Paper of Assistant Food Controller 16-12-2013 by rizwanchaudhry » Mon Dec 16, 2013 10:06 pm 1. Largest city of Pak at the time of creation 1947? Dacca 2. Who produce film on Quaid “Jinnah”? Jamil Dehlvi 3. Punjab Govt. installing Coal project with China at? Godani Baluchistan 4. What is meant by FIQAH? Islamic Jurisprudence 5. What is meant by INFAQ? Spending money in the way of Allah 6. Who won last FIFA world cup? Spain 7. Real name of Ibn-e-Safi? Israr Ahmad 8. Who wrote book “Jinnah to Zia”? Justice Munir 9. Shikwa or Jawab-e-Shikwa Iqbal ki kis book me he? Bang-e-Darra 10. “Little growth with wealth” (estrah ki ek book thi koi ) wrote by? 11. Second five year plan? 1960-65 12. Last Umayyad Caliph was? Marwan II 13. Headquarter of International Court of Justice? Hogue 14. Dick Cheney was the? V. President of USA 15. In 1909 which reforms were presented? Minto Morly 16. Where all RTC were held? London 17. Where Quaid presented his 14 points? Dehli 18. Isa rul Sanadid wrote by ? Sir, Syed 19. A tale of two cities related to? French Revolution 20. Who was reltated to Russian revolution? Linen 21. Which country head visit to Pakistan first? Pehalvi 22. Mountbaten succeeded by ? Weval 23. Alexander the great invasion of india? 326 bc 24. Davis cup is related to? Tenis 25. Pak won T20 in? 20009 26. Who offered to become granter in Kashmir Issue recently? UN Sectary 27. China became independent country in? 1949 28. -

Through the Critical Lenses of Cartoonists-Analysis of Political Cartoons

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. VIII, Issue 3/ June 2020 Impact Factor: 3.4546 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org History of Pakistanis’ Power Politics-from 1947 to 2020- through the Critical Lenses of Cartoonists- Analysis of Political Cartoons SHAZIA AKBAR GHILZAI Faculty Member, Department of Linguistics, QAU PhD Student, USPC Paris13, Research Lab TTN Paris 13 Abstract Political cartoons have the power to elicit a variety of responses because cartoon artists craft their work to express political views that are often controversial. We can say that political cartoons resemble time capsules. They provide information to the viewers about the time of their creation. Since, they denote particular events, they may seem to be locked in a given age. The article shows how the cartoons of a specific period represent the time and period in which they are produced. It reveals the function of cartoons beyond just humor or politics; cartoons not only record the history, the historical events and situations; but also provide critical lenses to view them simultaneously. It is indeed a very unique way for the creation, evaluation and maintenance of history and historical records. The present study reveals the history of Pakistanis’ power politics from 1947 to 2020 preserved through the medium of cartoons. The cartoonists evaluate and record particular events, situations and circumstances existing at one moment of time. The artists preserve the whole anecdote along with the context in a single frame uniquely. The editorial or political cartoons are based on topics of national interest; therefore, the present study recommends the preservation of cartoons systematically as National Archives1. -

July 16, 2017

INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES eekly E-BULLETINE-BULLETIN PAKISTAN PROJECT w July 10-26, 2017 This E-Bulletin focuses on major developments in Pakistan on weekly basis and brings them to the notice of strategic analysts and policy makers in India. EDITORIAL The Sharif family has rejected the JIT report and argued that the team had exceeded its mandate. Nawaz Sharif ’s he Joint Investigation Team (JIT) report has created lawyer Khawaja Haris, raised his objections in the Ta lot of speculation regarding the future of Prime Supreme Court on July 17 and dismissed the JIT report Minister Nawaz Sharif. While there was speculation as “eyewash” based on “mala fide” intentions and about the likely successor to Prime Minister Sharif, it “undertaken with a predisposed mind to malign and appears that he would not resign without giving a fight implicate the respondents in some wrongdoing or the - a stand supported by the party. The Supreme Court is other,” hearing the Panama papers case and examining the JIT report. It has also asked Imran Khan, the Chairperson The opposition, on the contrary, regards the report as of the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf, to explain the financial an incontrovertible proof of illegal money laundering source of his London flat. The political uncertainty also by the Sharif family and wants Nawaz to quit on moral reflected in the stock market as the market plummeted. grounds. As Nawaz refuses to resign, the opposition KSE-100 index declined 885 points (1.96 per cent) and hopes that the Supreme Court will ultimately find Nawaz settled at the end of the week at 44,337 points. -

A Study of Pakistan's Political Parties' Control Over State Resources and Redistribution in the Light of Panama Papers

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 6 No. 12 December 2018 A Study of Pakistan’s Political Parties’ Control Over State Resources and Redistribution in the Light of Panama Papers Spozmi TOOR Istanbul Aydin University Abstract The aim of the paper is to analyze and summarize the existing theoretical and secondary work on corruption in Pakistan. Two of the major political parties’ (PMLN and PPP) tenures will be discussed as they have ruled the country for about 30 years. Additionally, their control over the resources will be highlighted and how they have paved ways for corruption in every institution. The paper begins with a brief over-view of conceptualization of Corruption. This is followed by the major corruption leaks known as ‘Panama Papers’ which caused a bustle in Pakistani politics as one of the prominent political parties’ (PMLN) head and his family was named in those leaks that how they have been over the years money laundering to buy hidden off shore companies. The paper also addresses the important aspect of corruption and improper allocation of country’s resources with regards to the most powerful political parties of Pakistan PPP and PMLN. It discusses the most important factors of corruption with regards to the parties’ exercise within the parliament, election campaign, and overall control of the party over the resources of the country and its redistribution. Keywords: Corruption, Panama leaks, Pakistan, Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz Party, Pakistan people’s party, State 227 ISSN: 2411-5681 www.ijern.com Introduction The topic of my paper is “Pakistan Political Parties’ Control over State Resources and Redistribution in the Light of Panama Papers”. -

Purchase of Printed Books of Urdu

National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of Higher Education, Govt. of India Farogh-e-Urdu Bhawan, Jasola, New Delhi-110025 Date : 05.11.2019 SANCTION ORDER Consequent upon the approval of the „Bulk Purchase Committee‟ at its meeting held on 15.10.2019, sanction is accorded to the purchase of 435 Urdu books, 16 Arabic/Persian books and 81 periodicals/journals under the Bulk Purchase Scheme for the year 2020-21 costing Rs. 14196169/- (Rs. One Crore Forty One Lakh Ninety Six Thousand One Hundred Sixty Nine Only) (Rs.11085544/- for Urdu books, Rs.478645/- for Arabic/Persian books and Rs.2631980/- for periodicals/journals). Particulars of authors, editors, books and periodicals are as under : A) Urdu Books S. Reg Title Author/Applicant Price Theme Approve Payable No. No. With Address Content d Amount Quantity Autobiography, 00 Biography 1. 465 Aks-e-Qurban Abdullah Salman 300/- Biography 100 30000 ػ Abdullah Salman Riyazک ِل هـثبى (Pen Name) 26, Hains Road 1st Floor Egyptian Block angalore- 560051 (Karnataka) 2. 527 Urdu ki Maroof Asma Bano 400/- Biographies 75 30000 Khawateen Afsana Asma Niyani (PenName) of Urdu Nigar (vol.2) No. 4317, 14th Main 1st Women Cross Subramanyanagar writers اػؿّ کی هؼـّف عْاتیي (.Bangalore- 560021 (Kar اكنبًہ ًگبؿ )رلؼ۔۲( 3. 566 Beeswin Sadi ka Deepak Kanwal 350/- Biography 85 29750 Shahenshah: Dilip Sheikhpura, Budgam Kumar Kashmir (J&K) ثینْیں ؼٍی کب ىہٌيبٍ: ػلیپ کوبؿ 4. 126 Laddakh Ka Qaus- Hamid Ullah Hamid 250/- Biography 120 30000 e-Qaza R/o Tumlehal Pulwama (J&K) 192301 لؼّاط کب هْ ِك هقس 5.