Learning Analytics for the Global South Is Made Available Under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Program

FINAL PROGRAM May 3 – 8, 2008 • Town and Country Resort & Convention Center • San Diego, California SOLAR 2008 is presented by Featuring 37th ASES National Solar Conference 33rd National Passive Solar Conference 3rd Annual Renewable Energy Policy, Advocacy and Marketing Conference Solar Success! Training Event American Solar Energy Society Annual Meeting Society of Building Science Educators Annual Meeting Welcome On behalf of the American Solar Energy Society (ASES), the San Diego Renewable Energy Society (SDRES), the Northern California Solar Energy Association (NorCal Solar), the Redwood Empire Solar Living Association (RESLA), and the California Center for Sustainable Energy, welcome to SOLAR 2008! This year’s conference will build on the outstanding SOLAR successes of 2006 and 2007 where the dual role of renewable energy in climate and economic recovery, respectively, was clearly established. ASES Reports launched at these events — “Renewable Energy: A Key to Climate Recovery” and “Green Collar Jobs” — have been featured prominently in the public media. In 2008, we feel a new urgency about bringing together technology, policy and community solutions to address climate change, grow our economy and specifically look for solutions to reduce our carbon footprint. With a focus on renewable energy solutions in our communities and leadership to bring about change in our national energy policy we offer several new experiences at SOLAR 2008. First, we invite solar enthusiasts and those new to the field to participate more fully at SOLAR 2008 by opening our event on Public Days on Saturday and Sunday — at a discount for riders of mass transit! Featured will be demonstrations, films, speakers, and an exhibit hall with close to 200 booths. -

Korean Broadcasting System

Not ogged in Ta k Contributions Create account Log in Artic e Ta k Read Edit Hiew history Search Wikipedia Korean Broadcasting System From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates : 3,.52538GN 12A.91A3A1GE This article may be expanded with text translated [show ] from the corresponding article in Korean . (September 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Korean Broadcasting System ( KBS ) Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) Main page Contents (Hangul : 한국방송공사 ; Hanja : 韓 7eatured content Current e2ents 國放送公社 ; RR : Han-guk Bangsong Random artic e Ionate to Gongsa ; MR : Han'guk Pangsong Kongsa ) is 6ikipedia 6ikipedia store the national public broadcaster of South Korea . It was founded in 1927, and operates Logo used since 2 October 1984 1nteraction radio , television , and online services, being He p one of the biggest South Korean television About 6ikipedia Community porta networks . Recent changes Contact page Contents [ hide ] Too s 1 History 1.1 Beginnings in radio 6hat inks here Re ated changes 1.2 1950s–1960s - Move into Up oad K e television Specia pages Permanent ink 1.3 1970s - Expansion Page information 1.4 1980s - Advertising started after Main building of Korean Broadcasting System 6ikidata item controversial merger Native name 한국방송공사 Cite this page 1.5 1990s - SpinoE of EBS Hanja 韓國放送公社 Print/eCport 2 Structure Revised Han-guk Bangsong Gongsa Create a book 3 CEOs Romanization Iown oad as PI7 Printab e 2ersion 4 Channe s McCune– Han'guk Pangsong Kongsa 4.1 Terrestria te evision Reischauer 1n other projects -

Feasibility Study of a Solar Learning Labtm at WPI

y-- icif_ - )7// caw0,5-60.131 Feasibility Study of a Solar Learning LabTM at WPI E by a *k tic e *v, 9 Joseph Chapman Joseph Ledue Jason Wailgum Advisors Sponsor / Liaison Professor Richard F. Vaz Heliotronics / Mathew Amer Professor Kankana Mukherjee 0.0oi000iop• oosr 41111Insaimmun HELIOTRONICS products as reliable as sunrise Abstract Our group conducted a feasibility analysis for the installation of a Solar Learning LabTM at WPI. The Solar Learning LabTM is a concept developed by our sponsor, Heliotronics, which combines a solar photovoltaic array and a data acquisition system. To achieve our goal, we interviewed stakeholders, gathering information concerning logistical considerations, learning of contributions that they could offer, and discussing possible benefits of the installation. We analyzed the results to determine the feasibility of installation, incorporation into educational programs, and overall sustainability. 2 / 140 Authorship Page Everyone in our group contributed equally to this project. Acknowledgements We would like to thank our project advisors, Professors Richard Vaz and Kankana Mukherjee for supporting us throughout this semester and help us achieve a level that would not have been possible without them. In addition, we would like thank our project sponsor Heliotronics and especially its liaison, Matthew Amer. His support was quintessential to the successful completion of our project. We would also like to thank Solar Now Inc. for their generous donation of eight solar modules to better solar education in Worcester. Finally, we would like to thank our families and friends for their constant support and patience throughout the semester. 4/ 140 Executive Summary Introduction Conventional energy sources pollute the environment and adversely affect public health. -

Hingham High School, Hingham, MA

2014-2015 School Nominee Presentation Form ELIGIBILITY CERTIFICATIONS School and District’s Certifications The signatures of the school principal and district superintendent (or equivalents) on the next page certify that each of the statements below concerning the school’s eligibility and compliance with the following requirements is true and correct to the best of their knowledge. In no case is a private school required to make any certification with regard to the public school district in which it is located. 1. The school has some configuration that includes grades Pre-K-12. 2. The school has been evaluated and selected from among schools within the Nominating Authority’s jurisdiction, based on high achievement in the three ED-GRS Pillars: 1) reduced environmental impact and costs; 2) improved health and wellness; and 3) effective environmental education. 3. Neither the nominated public school nor its public school district is refusing the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (OCR) access to information necessary to investigate a civil rights complaint or to conduct a district wide compliance review. 4. OCR has not issued a violation letter of findings to the public school district concluding that the nominated public school or the public school district as a whole has violated one or more of the civil rights statutes. A violation letter of findings will not be considered outstanding if OCR has accepted a corrective action plan to remedy the violation. 5. The U.S. Department of Justice does not have a pending suit alleging that the public school or the public school district as a whole has violated one or more of the civil rights statutes or the Constitution’s equal protection clause. -

Download Download

JOURNAL OF LEARNING ANALYTICS Volume 1 ‐ Issue 2 (2014). Scientometrics as an Important Tool for the Growth of the Field of Learning Analytics. Journal of Learning Analytics, 1(2), 1‐4. Scientometrics as an Important Tool for the Growth of the Field of Learning Analytics Negin Mirriahi, Dragan Gasevic, Phil Long and Shane Dawson Editors, Journal of Learning Analytics ABSTRACT: This article introduces the special issue from SoLAR’s Learning Analytics and Knowledge conference. Learning analytics is an emerging field incorporating theory and practice from numerous disciplines to investigate how learner interactions with digital artefacts can provide actionable data to the learner herself, and educators about the learning process. As the field continues to expand there is a timely opportunity to evaluate its ongoing maturation. This evaluation could be in part informed by regular scientometric analyses from both the Journal and Conference publications. These analyses can collectively provide insight into the development of learning analytics more broadly and assist with the allocation of resources to under‐represented areas for example. KEYWORDS: Special issue, learning analytics, research, practice, Society for Learning Analytics Research, SoLAR, LAK’13 1 EDITORIAL We would like to dedicate this issue to our dear colleague and friend Erik Duval from Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium. Erik has been key figure in the development of the Society for Learning Analytics Research as both executive member and prominent researcher advancing the field. At LAK’14 Indianapolis, USA, Erik informed us that he was unable to attend the conference as he had been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma1. Despite undergoing a difficult medical treatment, Erik has maintained his unfailing level of energy, sense of humour and passion – traits which capture the hearts of those he interacts with2. -

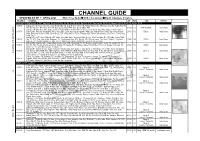

Channel Guide

CHANNEL GUIDE UPDATED AS OF 1ST APRIL 2021 FTA = Free To Air SCR = Scrambled Radio Channels in Italics FREQ/POL CHANNEL SR FEC CAS NOTES INTELSAT-38/AzerSpace2 at 45.1 deg East: Bom Az 238 El 51, Blr Az 250 El 49, Del 232 El 41, Chennai Az 252 El 46, Bhopal Az 238 El 44 Cal Az 248 El 35 11475 V Dialog DTH: Sony Six HD, Discovery World India HD, Star Movies Select HD, Animal Planet HD, AXN East Asia HD, Rugby PassTV S A HD, Star Sports 1 HD, Sony Ten2 HD, Star Sports select HD1, Star Sports Select HD2 32000 2/3 DVB-S2/8PSK India Beam T Dialog DTH: CBeebies Asia, Pogo, Cartoon Network HD+, A Plus Kids TV, Nickelodeon South East Asia, Baby TV Asia, Disney E 11515 V Junior India, National Geographic India, Sony BBC Earth, National Geographic Wild Asia, Animal Planet India, Discovery Channel 23700 5/6 DVB-S India Beam L L India, Discovery Science India, Tech Storm, TLC India, History TV 18, Travelxp HD, Travel Channel Asia, Sony Ten 1, Ten Cricket, I T Sony Ten 2 E Dialog DTH: HGTV Asia, Makeful, SET India, Sony Max India, Star Gold India, Colors, Star Plus India, Zee TV India, Colors Tamil, & 11555 V Sun TV, KTV, Star Vijay India, Kalaignar TV, Zee Cinema Asia, UTV Movies, B4U Movies India, Zee Tamil, Sirippoli, Zing Asia, 27690 3/5 DVB-S India Beam C Supreme TV, DTamil, Fashion TV Asia, Hi TV, NHK World Japan,, WakuWaku Japan South East Asia A Dialog DTH: Channel One, Rupavahini, Channel Eye, ITN, Vasantham TV, TV Derana, Swarnavahini, Sirasa TV, Shakthi TV, TV 1, B 11595 V Hiru TV, TNL TV, Art, Ada Derana 24x7, Siyatha TV, Haritha TV, -

D:\Channel Change & Guide\Chann

CHANNEL GUIDE UPDATED AS OF 1ST OCTOBER 2020 FTA = Free To Air SCR = Scrambled Radio Channels in Italics FREQ/POL CHANNEL SR FEC CAS NOTES INTELSAT-38/AzerSpace2 at 45 deg East: Bom Az 238 El 51, Blr Az 250 El 49, Del 232 El 41, Chennai Az 252 El 46, Bhopal Az 238 El 44 Cal Az 248 El 35 S 11475 V Dialog DTH: Sony Six HD, Discovery World India HD, Star Movies Select HD, Animal Planet HD, AXN East Asia HD, Rugby PassTV HD, Star Sports 1 HD, Sony A Ten2 HD, Star Sports select HD1, Star Sports Select HD2 32000 2/3 DVB-S2/8PSK India Beam T E 11515 V Dialog DTH: CBeebies Asia, Pogo, Cartoon Network, A+ Kids, Nickelodeon, Baby TV, Disney Junior, NGC, Sony BBC Earth, Nat Geo Wild, Animal Planet, L Discovery, Discovery Science, TechStorm, TLC, History TV18, Travel XP, Dsport 1, Sony Ten 1, Ten Cricket, Sony Ten 2 23700 5/6 DVB-S India Beam L I 11555 V Dialog DTH: HGTV Asia, E!, SET India, Sony Max, Star Gold, Colors, Star Plus, Zee TV, Colors Tamil, Sun TV, KTV, Star Vijay, Kalainagar TV, Zee Cinema, UTV T E Movies, B4U Movies, Zee Tamil, Sirippoli, WakuWaku Japan, Celestial Classic Movies, Fashion TV Asia, Hi TV, TVN Asia, WakuWaku Japan South East Asia 27690 3/5 DVB-S India Beam & 11595 V Dialog DTH: Channel One, Rupavahini, Channel Eye, ITN, Vasantham TV, TV Derana, Swarnavahini, Sirasa TV, Shakti TV, TV 1, Hiru TV, TNL, Art, Ada Derana C 24x7, Siyatha TV, Pragna TV, TV Didula, Riddhi TV, Citi Hitz, 7th Circuit, Rangiri TV, Revision TV, UTV Tamil, Udhayam TV, Nenasa TV 10 27690 5/6 DVB-S India Beam A Dialog DTH: Eurosport 1, Outdoor Channel, -

REGISTERED PROVIDERS for the NABCEP® ENTRY LEVEL PV EXAM Please Note: This List Is in Alphabetical Order by STATE/Territory

REGISTERED PROVIDERS FOR the NABCEP® ENTRY LEVEL PV EXAM Please Note: This list is in alphabetical order BY STATE/Territory There are currently: 250 Providers of the NABCEP PV Entry Level Exam Please contact the provider(s) for more information about any course(s) listed below. FACILITY/INSTITUTION COURSE NAME(S) ALABAMA – Auburn Solar Photovoltaics This course will provide 40 hours of training covering Smart North America the NABCEP required learning objectives in preparation 570 Devall Drive Suite 303 for the Entry Level Exam. Participants will get hands- Auburn, AL 36832 on and classroom training. Completion of this course will result in students who are prepared to enter the field Contact: Ruth Page-Nelson and obtain further training and experience needed to become proficient installers. E-mail: [email protected] Tele. (800) 764-3085 www.smartgridnorthamerica.com ALABAMA – Decatur REN 115 This course covers basic principles and design of photovoltaic (PV) systems. Upon completion of the Calhoun State Community College course, students should have demonstrated a basic Department of Renewable Energy understanding of PV markets and applications, safety P.O. Box 2216 basics, electricity basics, solar energy fundamentals, PV Decatur, AL 35609-2216 module fundamentals, system components, PV system sizing and electrical and mechanical design, and performance analysis, maintenance and troubleshooting. Contact: Jerry W. Adams, Director The course prepares the student to take the NABCEP ACECET/Renewable Energy PV Entry Level Exam. Though highly recommended, E-mail: [email protected] taking the exam is not a mandatory requirement of the Tele. (256) 306-2642 course. www.calhoun.edu ARIZONA – Flagstaff Photovoltaic System Installation Course This course will provide an overview of the basic PV system design and application. -

CONNECTIONS After School Program

Holyoke Public Schools Connections Holyoke Public Schools Volume 10, Issue 2 A Community Working Together Winter 2012 An Open Letter to the Holyoke School Community Educator Evaluation By David Dupont, Superintendent of Schools The state plan to overhaul educator evaluation is an (MTA), which is one of the DESE approved vendors ongoing process which is scheduled to be put into assisting districts in their work to implement the Inside this issue: effect for all school districts in Massachusetts for the evaluation model. Teachers, nurses, district adminis- 2012-2013 school year. There are, however, some trators, and all other DESE licensed personnel will all districts-those which have Level 4 schools and those be subject to the new system. We obviously intend School News 2-8 which volunteered to implement a year earlier-that to be in full compliance with this state-wide initiative, have been working on implementation for the 2011- however I feel very strongly that all of this will be 2012 school year. (The new system is for the indi- much more effective and meaningful if we can move vidual Level 4 schools and not the entire district this across the boundary that many times stands between School Briefs 9 school year.) The evaluation overhaul is a major compliance and ownership. change in how evaluations have been traditionally performed in the past. There is a great amount of Athletics 10 related information on the Massachusetts Depart- ment of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) website http://www.doe.mass.edu/, and we will be providing the principals any updates that we receive from the department. -

The Complete

International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications (IJONTE) April 2016 Volume: 7 Issue: 2 ISSN 1309-6249 http://ijonte.org International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April 2016 Volume: 7 Issue: 2 ISSN 1309-6249 Contact Addresses Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya, Gazi Üniversitesi, Gazi Eğitim Fakültesi, Eğitim Bilimleri Bölümü Teknik Okullar Ankara/Türkiye E. Mail: [email protected] Prof. Dr. Uğur Demiray, Anadolu Üniversitesi, İletişim Bilimleri Fakültesi, Yunusemre Kampüsü, 26470 Eskişehir/Türkiye E. Mail: [email protected] Phone: +905422322167 Abstracting & Indexing International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications (IJONTE) is currently indexed, abstracted and listed starting with the first issue in: i Copyright © International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications / www.ijonte.org International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April 2016 Volume: 7 Issue: 2 ISSN 1309-6249 ii Copyright © International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications / www.ijonte.org International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April 2016 Volume: 7 Issue: 2 ISSN 1309-6249 Sponsors Editors Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya, Gazi University- Turkey Prof. Dr. Ugur Demiray, Anadolu University- Turkey Associate Editors Assoc. Prof. Dr. Beyhan Zabun, Gazi University- Turkey Assist. Prof. Dr. Ilknur Istifci, Anadolu University- Turkey Dr. Nazan Dogruer, Eastern Mediterranean University- TRNC Dr. Ramadan Eyyam, Eastern Mediterranean University- TRNC Dr. Ufuk Tanyeri, Ankara University- Turkey Assistant Editor Ipek Menevis, Eastern Mediterranean University- TRNC Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Ali H. Raddaoui, University of Sfax- Tunisia Prof. Dr. Abdul Hakim Juri, University of Kuala Lumpur- Malaysia Prof. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 449 730 HE 033 730 AUTHOR Tsang, Edmund, Ed. TITLE Projects That Matter: Concepts and Models for Service-Learning in Engineering. AAHE's Series on Service-Learning in the Disciplines. INSTITUTION American Association for Higher Education, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-1-56377-019-9 PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 190p.; For other documents in this series, see HE 033 726-743. Initial funding for this series was supplied by Campus compact. AVAILABLE FROM American Association for Higher Education, One Dupont Circle, Suite 330, Washington, DC 20036-1110 ($28.50). Tel: 202-293-6440; Fax: 202-293-0073; Web site: www.aahe.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Students; Curriculum Development; *Engineering; *Engineering Education; Higher Education; Intellectual Disciplines; School Community Relationship; *Service Learning; *Student Participation ABSTRACT This volume, the 14th in a series of monographs on service learning and academic disciplinary areas, is designed as a practical guide for faculty seeking to integrate service learning into an engineering course. The volume also deals with larger issues in engineering education and provides case studies of service-learning courses. The articles are: (1) "What I Never Learned in Class: Lessons from Community-Based Learning" (Gerald S. Eisman);(2) "Service-Learning as a Pedagogy for Engineering: Concerns and Challenges" (Edmund Tsang); (3) "Service-Learning Reflection for Engineering: A Faculty Guide" (Jennifer Moffat and Rand Decker); (4) "How To Institutionalize Service-Learning into the Curriculum of an Engineering Department: Designing a Workable Plan" (Peter T. Martin and James Coles);(5) "Professional Activism: Reconnecting Community, Campus, and Alumni through Acts of Service" (Rand Decker); (6) "EPICS: Service-Learning by Design" (Edward J. -

C Ntent 11 September 2017 L

24 July- C NTENT 11 September 2017 www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com the C NTENTASIA Antv bets on Indian drama to keep #1 slot Indonesian station beats back broadcast giants #keepcalmandstreamon This year’s ContentAsia Summit takes a long deep breath, Indonesian free-TV station Antv premieres Indian series Jamai Raja (King of Hearts) channels its inner Zen, and then dives right into the twists this week, betting again on a genre that and turns of Asia’s latest content story, an epic tale of has helped drive the small station to the top of the country’s ratings charts. drama, separation, destruction, reflection, creativity, The David-and-Goliath situation plays out against the backdrop of real-life innovation, technology and – ultimately – drama as the long-running tug of war transformation and growth. over MNCTV/TPI resurfaces. You’ll find the whole story on page 2 Turner kicks off 7-8 September 2017 mobile-first series PARKROYAL on Pickering • Singapore No longer just a pay-TV business, says president Ricky Ow www.contentasiasummit.com Turner has commissioned its first mobile-first video series in Asia, taking the regional or- ganisation another step into a future built on relevance and engagement across all platforms. You’ll find the whole story on page 7 C NTENTASIA 24 July-11 September 2017 Page 2. Indonesia’s Antv bets on Indian drama to keep #1 slot Antv beats back broadcast giants as industry watches MNCTV vs TPI drama resurface Indonesian free-TV station Antv premieres locally produced dramas, Jodoh Wasiat and Siddharth in their pursuit of happily Hindi series Jamai Raja (King of Hearts) Bapak and Kecil-Kecil Mikir Jadi Manten.