How Banff National Park Became a Hydroelectric Storage Reservoir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Quality Study of Waiparous Creek, Fallentimber Creek and Ghost River

Water Quality Study of Waiparous Creek, Fallentimber Creek and Ghost River Final Report Prepared by: Daniel Andrews Ph.D. Clearwater Environmental Consultants Inc. Prepared for: Alberta Environment Project 2005-76 February, 2006 Pub No. T/853 ISBN: 0-7785-4574-1 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-4575-X (On-Line Edition) Any comments, questions, or suggestions regarding the content of this document may be directed to: Environmental Management Southern Region Alberta Environment 3rd Floor, Deerfoot Square 2938 – 11th Street, N.E. Calgary, Alberta T3E 7L7 Phone: (403) 297-5921 Fax: (403) 297-6069 Additional copies of this document may be obtained by contacting: Information Centre Alberta Environment Main Floor, Oxbridge Place 9820 – 106th Street Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2J6 Phone: (780) 427-2700 Fax: (780) 422-4086 Email: [email protected] ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Increased usage of the Ghost -Waiparous basin for random camping and off-highway vehicles (OHVs) has raised concerns among stakeholders that these activities are affecting water quality in the Ghost, Waiparous and Fallentimber Rivers. This report to Alberta Environment attempts to determine whether there is a linkage between these activities and water quality in these three rivers and documents baseline water quality prior to the implementation of an access management plan by the Alberta Government. Water quality monitoring of these rivers was conducted by Alberta Environment during 2004 and 2005. Continuous measurements of turbidity (as a surrogate for total suspended solids), pH, conductivity, dissolved oxygen and temperature were taken in Waiparous Creek, upstream at the Black Rock Trail and downstream at the Department of National Defense base from early May to late July, 2004. -

English Language Arts and Social Reproduction in Alberta

University of Alberta Reading Between the Lines and Against the Grain: English Language Arts and Social Reproduction in Alberta by Leslie Anne Vermeer A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theoretical, Cultural and International Studies in Education Department of Educational Policy Studies © Leslie Anne Vermeer Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of Timothy James Beechey (1954–2011), who represented for me everything that teaching and learning are and can be; and to Bruce Keith and Zachary Keith, because no one earns a doctorate by herself. Abstract Alberta's 2003 High School English Language Arts curriculum produces differential literacies because it grants some students access to high-status cultural knowledge and some students access to merely functional skills. This differential work reflects an important process in sorting, selecting, and stratifying labour and reproducing stable, class-based social structures; such work is a functional consequence of the curriculum, not necessarily recognized or intentional. -

Steward : 75 Years of Alberta Energy Regulation / the Sans Serif Is Itc Legacy Sans, Designed by Gordon Jaremko

75 years of alb e rta e ne rgy re gulation by gordon jaremko energy resources conservation board copyright © 2013 energy resources conservation board Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication ¶ This book was set in itc Berkeley Old Style, designed by Frederic W. Goudy in 1938 and Jaremko, Gordon reproduced in digital form by Tony Stan in 1983. Steward : 75 years of Alberta energy regulation / The sans serif is itc Legacy Sans, designed by Gordon Jaremko. Ronald Arnholm in 1992. The display face is Albertan, which was originally cut in metal at isbn 978-0-9918734-0-1 (pbk.) the 16 point size by Canadian designer Jim Rimmer. isbn 978-0-9918734-2-5 (bound) It was printed and bound in Edmonton, Alberta, isbn 978-0-9918734-1-8 (pdf) by McCallum Printing Group Inc. 1. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. Book design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. 2. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board — History. 3. Energy development — Government policy — Alberta. 4. Energy development — Law and legislation — Alberta. 5. Energy industries — Law and legislation — Alberta. i. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. ii. Title. iii. Title: 75 years of Alberta energy regulation. iv. Title: Seventy-five years of Alberta energy regulation. hd9574 c23 a4 j37 2013 354.4’528097123 c2013-980015-8 con t e nt s one Mandate 1 two Conservation 23 three Safety 57 four Environment 77 five Peacemaker 97 six Mentor 125 epilogue Born Again, Bigger 147 appendices Chairs 154 Chronology 157 Statistics 173 INSPIRING BEGINNING Rocky Mountain vistas provided a dramatic setting for Alberta’s first oil well in 1902, at Cameron Creek, 220 kilometres south of Calgary. -

UPDATED APRIL 5, 2018 the Canadian Rockies Comprise the Canadian Segment of the North American Rocky Mountains

“Canadian Splendor — Banff to Jasper” Rolling Rally August 21-29, 2018 Rally Fee: $2,700 Per Couple UPDATED APRIL 5, 2018 The Canadian Rockies comprise the Canadian segment of the North American Rocky Mountains. With hundreds of jagged, ice-capped peaks, the Canadian Rockies span the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. This majestic, awe-inspiring mountain range is a region of alpine lakes carved by glaciers, diverse wildlife, outdoor recreation sites, and miles and miles of scenic roads and highways. We hope you enjoy your summer “Canadian Splendor” Marathon Club adventure! Event Itinerary Pre-Rally Arrival Day—Monday, August 20 Day Two—Wednesday, August 22 • Arrive Banff National Park, where we have Sites • Guided Bus Tour of Banff Townsite at Two Adjacent Campgrounds: Tunnel Mountain (9:00 – 10:50 am). Located at an elevation of Trailer Court (30- or 50-amp power, water and 4,500 feet, Banff Townsite is the highest town in sewer); and Tunnel Mountain II (50-amp power, Canada. Sights you’ll see during this morning’s tour no water and sewer at sites — a dump station and include Surprise Corner, the Banff Springs Hotel potable water are available) and Bow Falls (these falls were featured in the Because the rally begins Tuesday, there are no 1953 Marilyn Monroe film, “River of No Return”). activities today; however, today’s site fee is included There will also be a one-hour tour at the birthplace in your rally fee. Note: The annual “Individual of Canada’s national parks, Cave and Basin Discovery Pass” each person will need to buy for the National Historic Site. -

The Little Bow Gets Bigger – Alberta's Newest River

ALBERTA WILDERNESS Article ASSOCIATION Wild Lands Advocate 13(1): 14 - 17, February 2005 The Little Bow Gets Bigger – Alberta’s Newest River Dam By Dr. Stewart B. Rood, Glenda M. Samuelson and Sarah G. Bigelow The Little Bow/Highwood Rivers Project includes Alberta’s newest dam and provides the second major water project to follow the Oldman River Dam. The controversy surrounding the Oldman Dam attracted national attention that peaked in about 1990, and legal consideration up to the level of the Supreme Court over federal versus provincial jurisdiction and the nature and need for environmental impact analysis. A key outcome was that while environmental matters are substantially under provincial jurisdiction, rivers involve fisheries, navigation, and First Nations issues that invoke federal responsibility. As a consequence, any major water management project in Canada requires both provincial and federal review. At the time of the Oldman Dam Project, three other proposed river projects in Alberta had received considerable support and even partial approval. Of these, the Pine Coulee Project was the first to advance, probably partly because it was expected to be the least controversial and complex. That project involved the construction of a small dam on Willow Creek, about an hour south of Calgary. A canal from that dam diverts water to be stored in a larger, offstream reservoir in Pine Coulee. That water would then be available for release back into Willow Creek during the late summer when flows are naturally low but irrigation demands are high. Pine Coulee was generally a dry prairie coulee and reservoir flooding did not inundate riparian woodlands or an extensive stream channel. -

Fax Coversheet

December 20, 2010 Using water reservations to protect the aesthetic values associated with water courses: a note on the Spray River (Banff) By Nigel Bankes Documents commented on:: Order in Council 546\49; South Saskatchewan Basin Water Allocation Regulation, Alta. Reg. 307/1991 (rescinded by Bow, Oldman and South Saskatchewan River Basin Water Allocation Order, Alta. Reg. 171/2007); Alberta Environment, TransAlta Utilities (TAU) licence for the Spray River development. I have been doing some work on Crown water reservations over the last few months and in the course of that came across an example of what at first glance seemed to be the use of a water reservation to preserve the aesthetic qualities of a watercourse. The example also has an interesting constitutional twist that is worth reflecting on. When Alberta was created in 1905 it took its place in confederation without the ownership or administration and control of its natural resources, including water. Canada (the Dominion) continued to manage lands and resources in the province for the benefit of the national interest. That included using Dominion lands to encourage immigration, but it also included the creation, maintenance and expansion of national parks to encourage tourism and to protect spectacular landscapes. With the transfer of the administration and control of natural resources from Canada to Alberta in 1930 it was necessary to deal with retained federal lands. These lands included Indian reserves (about which there has been a lot of litigation over the years) and national parks (which have seen less litigation). I wrote about the constitutional status of national parks a good number of years ago: "Constitutional Problems Related to the Creation and Administration of Canada's National Parks" in J.O. -

(Now Rt> Hon.) WL Mackenzie Ki

PROVINCIAL GENERAL ELECTIONS 877 having carried 118 constituencies, took office on the resignation of Mr. Meighen, with Hon. (now Rt> Hon.) W. L. Mackenzie King as Prime Minister. One of the outstanding features of the election was the rise of a third party, the Progressives, which, under the leadership of Hon. T. A. Crerar, carried 65 seats in Ontario and the West. Besides these the Labour party elected two members, one in Winni peg and one in Calgary. On the meeting of Parliament the Progres sives renounced the position of official Opposition, to which their numbers gave them a claim; the Conservatives, therefore, under the leadership of Mr. Meighen, constitute the official Opposition in the Fourteenth Parliament. Provincial General Elections.—In Saskatchewan at a general election on June 9, 1921, the Liberal Government of Premier Martin was returned to power with a slightly diminished majority, carrying 45 out of 63 seats. In Alberta, at a general election on July 18, 1921, the Liberal Government of Hon. Chas. Stewart was defeated by the Farmers' organization, which secured 38 out of the 61 seats in the Legislature. On August 13, their leader, Hon. Herbert Greenfield, took office as Premier. In Manitoba, at a general election which took place on July 18, 1922, the Norris Government was defeated, the United Farmers securing a working majority and organizing a government headed by the Hon. John Bracken, formerly principal of the Manitoba Agri cultural College. Acquisition of the Grand Trunk by the Government.— This subject is dealt with in the sub-section on steam railways, pages 527-528. -

Spray Valley Summer Trails

Legend Alberta/British Columbia Border B a ROADS n f POWER LINES f T HORSE/MOUNTAIN BIKING/HIKING ra il MOUNTAIN BIKING/HIKING TRAILS 6 G k e HIKING TRAILS ONLY m o r ( g UNDESIGNATED TRAILS o e n TRAIL DISTANCES 1.5 km t .. e o w w PARK BOUNDARY a y n ) 3 .5 k m Canmore Nordic G Centre o a Alpine Club t C 1 of Canada r e Grassi e k Lakes 1 9 .3 Grassi Goat Lakes km Creek to 3.5 km Banff Bow River Campground Bow River 742 Eau Claire KANANASKIS Sp 23 COUNTRY Driftwood Boat Launch Spray Lakes West BANFF NATIONAL PARK Sparrowhawk e id Spray Lake S t s e W S m i t h - D o r r i e n / S p r a y T r a i l Canyon Dam ek re r C B lle ry 9 km a B u n u B 1 km Guinns t l l Cr e Pass e Buller r e k ( M B Mountain a t. nf f P Buller ar Mount Pond k) Shark (Winter Only) ) Watridge k r Lake Mount a Shark P Watridge f f n Lake a 742 B 3.7 km ( s s a P Karst r Spring NORTH e Mt Engadine s 0.8 km i l l Lodge a P Peter Lougheed Provincial Park Spray Valley Spray Summer Trails Trails For Hikers, Mountain Bikers & Horseback Riders The way to the Spray Valley TRAIL ACCESS REMARKS Backcountry Permits WATRIDGE LAKE Mount Shark Day Use An easy trail to a beautiful emerald Backcountry permits are required to camp at any of the backcountry 3.7 km one way lake. -

NYU Radiology CME in Banff MONDAY, August 3 TUESDAY

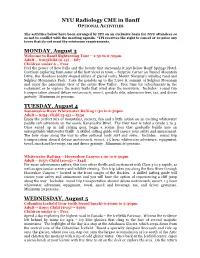

NYU Radiology CME in Banff OPTIONAL ACTIVITIES The activities below have been arranged by TPI on an exclusive basis for NYU attendees so as not to conflict with the meeting agenda. *TPI reserves the right to cancel or re-price any tours that do not meet the minimum requirements. MONDAY, August 3 Welcome to Banff Sightseeing Tour – 1:30 to 6:30pm Adult -- $105Child (6-15) -- $87 Children under 6 – Free Feel the power of Bow Falls and the beauty that surrounds it just below Banff Springs Hotel. Continue exploring from some of the best views in town – Surprise Corner on Tunnel Mountain Drive, the Hoodoos (oddly shaped pillars of glacial rock), Mount Norquay’s winding road and Sulphur Mountain’s Peak. Take the gondola up to the 7,500 ft. summit of Sulphur Mountain and enjoy the panoramic view of the entire Bow Valley. Free time for refreshments in the restaurant or to explore the many trails that wind atop the mountain. Includes: round trip transportation aboard deluxe motorcoach, escort, gondola ride, admission fees, tax, and driver gratuity. Minimum 20 persons. TUESDAY, August 4 Kananaskis River Whitewater Rafting 1:30 to 6:30pm Adult -- $154; Child (5-15) -- $139 Enjoy the perfect mix of mountains, scenery, fun and a little action on an exciting whitewater paddle raft adventure on the scenic Kananaskis River. The river tour is rated a Grade 2 to 3. Once suited up in full rafting gear, begin a scenic float that gradually builds into an unforgettable whitewater thrill! A skilled rafting guide will ensure your safety and amusement. -

Alberta Tools Update with Notes.Pdf

1 2 3 A serious game “is a game designed for a primary purpose other than pure entertainment. The "serious" adjective is generally prepended to refer to video games used by industries like defense, education, scientific exploration, health care, emergency management, city planning, engineering, and politics.” 4 5 The three inflow channels provide natural water supply into the model. The three inflow channels are the Bow River just downstream of the Bearspaw Dam and the inflows from the Elbow and Highwood River tributaries. The downstream end of the model is the junction with the Oldman River which then forms the South Saskatchewan River. The model includes the Glenmore Reservoir located on the Elbow River, upstream of the junction with the Bow River. 6 The Tutorial Mode consists of two interactive tutorials. The first tutorial introduces stakeholders to water management concepts and the second tutorial introduces the users to the Bow River Sim. The tutorials are guided by “Wheaton” an animated stalk of wheat who guides the users through the tutorials. 7 - Exploration Mode lets people play freely with sliders, etc, and see what the results are. - The Challenge Mode explores the concept of goal-oriented play which helps users further explore and learn about the WRMM model and water management. In Challenge Mode, the parameters that could be changed were limited, and the stakeholders are provided with specific learning objectives. Three challenges are introduced in this order: Reservoir Challenge, Calgary Challenge and Priority Challenge. 8 9 Flood Hazard Identification Program Objectives 10 Overview of our flood mapping web application – Multiple uses Supports internal and external groups Co-funded by Government of Alberta and Government of Canada through the National Disaster Mitigation program. -

RURAL ECONOMY Ciecnmiiuationofsiishiaig Activity Uthern All

RURAL ECONOMY ciEcnmiIuationofsIishiaig Activity uthern All W Adamowicz, P. BoxaIl, D. Watson and T PLtcrs I I Project Report 92-01 PROJECT REPORT Departmnt of Rural [conom F It R \ ,r u1tur o A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta W. Adamowicz, P. Boxall, D. Watson and T. Peters Project Report 92-01 The authors are Associate Professor, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Forest Economist, Forestry Canada, Edmonton; Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton and Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton. A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta Interim Project Report INTROI)UCTION Recreational fishing is one of the most important recreational activities in Alberta. The report on Sports Fishing in Alberta, 1985, states that over 340,000 angling licences were purchased in the province and the total population of anglers exceeded 430,000. Approximately 5.4 million angler days were spent in Alberta and over $130 million was spent on fishing related activities. Clearly, sportsfishing is an important recreational activity and the fishery resource is the source of significant social benefits. A National Angler Survey is conducted every five years. However, the results of this survey are broad and aggregate in nature insofar that they do not address issues about specific sites. It is the purpose of this study to examine in detail the characteristics of anglers, and angling site choices, in the Southern region of Alberta. Fish and Wildlife agencies have collected considerable amounts of bio-physical information on fish habitat, water quality, biology and ecology. -

Information Package Watercourse

Information Package Watercourse Crossing Management Directive June 2019 Disclaimer The information contained in this information package is provided for general information only and is in no way legal advice. It is not a substitute for knowing the AER requirements contained in the applicable legislation, including directives and manuals and how they apply in your particular situation. You should consider obtaining independent legal and other professional advice to properly understand your options and obligations. Despite the care taken in preparing this information package, the AER makes no warranty, expressed or implied, and does not assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. For the most up-to-date versions of the documents contained in the appendices, use the links provided throughout this document. Printed versions are uncontrolled. Revision History Name Date Changes Made Jody Foster enter a date. Finalized document. enter a date. enter a date. enter a date. enter a date. Alberta Energy Regulator | Information Package 1 Alberta Energy Regulator Content Watercourse Crossing Remediation Directive ......................................................................................... 4 Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 4 How the Program Works .......................................................................................................................