The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Seriesdraws On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autecology of the Sunda Pangolin (Manis Javanica) in Singapore

AUTECOLOGY OF THE SUNDA PANGOLIN (MANIS JAVANICA) IN SINGAPORE LIM T-LON, NORMAN (B.Sc. (Hons.), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2007 An adult male Manis javanica (MJ17) raiding an arboreal Oceophylla smaradgina nest. By shutting its nostrils and eyes, the Sunda Pangolin is able to protect its vulnerable parts from the powerful bites of this ant speces. The scales and thick skin further reduce the impacts of the ants’ attack. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My supervisor Professor Peter Ng Kee Lin is a wonderful mentor who provides the perfect combination of support and freedom that every graduate student should have. Despite his busy schedule, he always makes time for his students and provides the appropriate advice needed. His insightful comments and innovative ideas never fail to impress and inspire me throughout my entire time in the University. Lastly, I am most grateful to Prof. Ng for seeing promise in me and accepting me into the family of the Systematics and Ecology Laboratory. I would also like to thank Benjamin Lee for introducing me to the subject of pangolins, and subsequently introducing me to Melvin Gumal. They have guided me along tremendously during the preliminary phase of the project and provided wonderful comments throughout the entire course. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) provided funding to undertake this research. In addition, field biologists from the various WCS offices in Southeast Asia have helped tremendously throughout the project, especially Anthony Lynam who has taken time off to conduct a camera-trapping workshop. -

2 Parks & Waterbodies Plan

SG1 Parks & Waterbodies Plan AND IDENTITY PLAN S UBJECT G ROUP R EPORT O N PARKS & WATERBODIES PLAN AND R USTIC C OAST November 2002 SG1 SG1 S UBJECT G ROUP R EPORT O N PARKS & WATERBODIES PLAN AND R USTIC C OAST November 2002 SG1 SG1 SG1 i 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Parks & Waterbodies Plan and the Identity Plan present ideas and possibilities on how we can enhance our living environment by making the most of our natural assets like the greenery and waterbodies and by retaining places with local identity and history. The two plans were put to public consultation from 23 July 2002 to 22 October 2002. More than 35,000 visited the exhibition, and feedback was received from about 3,600 individuals. Appointment of Subject Groups 1.2 3 Subject Groups (SGs) were appointed by Minister of National Development, Mr Mah Bow Tan as part of the public consultation exercise to study proposals under the following areas: a. Subject Group 1: Parks and Waterbodies Plan and the Rustic Coast b. Subject Group 2: Urban Villages and Southern Ridges & Hillside Villages c. Subject Group 3: Old World Charm 1.3 The SG members, comprising professionals, representatives from interest groups and lay people were tasked to study the various proposals for the 2 plans, conduct dialogue sessions with stakeholders and consider public feedback, before making their recommendations to URA on the proposals. Following from the public consultation exercise, URA will finalise the proposals and incorporate the major land use changes and ideas into the Master Plan 2003. -

Insider People · Places · Events · Dining · Nightlife

APRIL · MAY · JUNE SINGAPORE INSIDER PEOPLE · PLACES · EVENTS · DINING · NIGHTLIFE INSIDE: KATONG-JOO CHIAT HOT TABLES CITY MUST-DOS AND MUCH MORE Ready, set, shop! Shopping is one of Singapore’s national pastimes, and you couldn’t have picked a better time to be here in this amazing city if you’re looking to nab some great deals. Score the latest Spring/Summer goods at the annual Fashion Steps Out festival; discover emerging local and regional designers at trade fair Blueprint; or shop up a storm when The Great Singapore Sale (3 June to 14 August) rolls around. At some point, you’ll want to leave the shops and malls for authentic local experiences in Singapore. Well, that’s where we come in – we’ve curated the best and latest of the city in this nifty booklet to make sure you’ll never want to leave town. Whether you have a week to deep dive or a weekend to scratch the surface, you’ll discover Singapore’s secrets at every turn. There are rich cultural experiences, stylish bars, innovative restaurants, authentic local hawkers, incredible landscapes and so much more. Inside, you’ll find a heap of handy guides – from neighbourhood trails to the best eats, drinks and events in Singapore – to help you make the best of your visit to this sunny island. And these aren’t just our top picks: we’ve asked some of the city’s tastemakers and experts to share their favourite haunts (and then some), so you’ll never have a dull moment exploring this beautiful city we call home. -

Communities Go Car-Lite Streets Are the New Venue for Passion Projects

ISSUE 04 · 2016 SkylineInsights into planning spaces around us Communities go car-lite Streets are the new venue for passion projects Why the birds returned to Kranji Marshes The evolution of urban resilience ISSUE 04 · 2016 Editorial team Serene Tng Cassandra Yeap Contributing writers Jennifer Eveland Timothy Misir Justin Zhuang Ruthe Kee Sarah Liu Adora Wong Photographers Mark Teo Louis Kwok Chee Boon Pin Wilson Pang Guest contributor Jeannie Quek CLASSICALLY SPONTANEOUS: THE PEOPLE AT SERANGOON ROAD’S ‘LITTLE INDIA’ FORM THE BACKBONE OF A CONSERVATION AREA THAT IS ALWAYS ADAPTING EVEN AS IT STAYS THE SAME. WE CAPTURE SOME OF THEIR COLOURFUL TALES ON PAGE 21. Editorial assistant Shannon Tan Design Silicon+ Contents Published by 03 The road to resilience 23 Documenting Little India’s charm The importance of urban resilience Timeless, organic and always colourful amid uncertainties Address 45 Maxwell Road 26 Imagining streets without cars The URA Centre 06 Restoring Singapore’s largest Creativity and community turn Singapore 069118 freshwater marshland roads vibrant We welcome feedback and How Kranji Marshes was rehabilitated submissions. Contact us at 29 Activating spaces through music [email protected] 10 Keeping Marina Bay cool Recycled pianos bond people in +65 6321 8215 Delving into the world’s largest public spaces Connect with us at underground district cooling system www.ura.gov.sg/skyline 30 At a glance facebook.com/URASingapore 14 Towards a car-lite Singapore Initiatives shaping neighbourhoods twitter.com/URAsg Going car-lite needs more than just and spaces around us Some of the articles in this cycling paths issue are also published in Going Places Singapore, 19 What does it take to keep a www.goingplacessingapore.sg place alive? Experts explain who and what No part of this publication make a place memorable may be reproduced in whole or in part without the prior consent of the URA. -

02 Mar 1999 Sunday 7 Nov 99 • Launch Ceremony at Marina City

Date Published: 02 Mar 1999 Sunday 7 Nov 99 Launch ceremony at Marina City Park organised by ENV and NParks. The ceremony will include presentation of prizes to winners of the Green Leaf Award and the Island-wide Cleanest Precinct Competition for the RC zone and food centre categories. 2000 trees will be planted by 37 constituency advisors and some 3000 constituents at the Marina Bay and Marina South coastlines after the launch ceremony. Guest-of-Honour: Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong. Contact person: Mr Tan Eng Sang Chairman Launch Sub-Committee ENV Tel: 7319680 Fax: 7319725 Plant-a-thon at Marina City Park organised by SEC and Esso, featuring talks and workshops on plants, a "Plants For Clean Air" exhibition, a plant clinic, a plant adoption scheme and a plant sale. Contact person: Mrs Penelope Phoon-Cohen Executive Director SEC Tel: 3376062 Fax: 3376035 Greenathon VIII ? Recycling of cans at Marine Parade organised by the Association of Muslim Professionals (AMP) and supported by SEC. Contact person: Ms Zainab Abdul Latif Executive AMP Tel: 3460911 Fax: 3460922 Monday 8 Nov 99 Clean and Green Week Carnival 99 at Ubi Ave 1 organised by Marine Parade Town Council. Contact person: Ms Grace Wong Public Relations Executive Marine Parade Town Council Tel: 2416012 ext 17 Fax: 4440919 9.30 am Launch of Adoption of Kampong Java Park by KK Women's and Children's Hospital Guest-of-Honour: Dr John Chen, Minister of State for National Development and for Communications and Information Technology Contact person: Ms Terri Oh Public Affairs Manager -

Singapore | October 17-19, 2019

BIOPHILIC CITIES SUMMIT Singapore | October 17-19, 2019 Page 3 | Agenda Page 5 | Site Visits Page 7 | Speakers Meet the hosts Biophilic Cities partners with cities, scholars and advocates from across the globe to build an understanding of the importance of daily contact with nature as an element of a meaningful urban life, as well as the ethical responsibility that cities have to conserve global nature as shared habitat for non- human life and people. Dr. Tim Beatley is the Founder and Executive Director of Biophilic Cities and the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, in the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, School of Architecture at the University of Virginia. His work focuses on the creative strategies by which cities and towns can bring nature into the daily lives of thier residents, while at the same time fundamentally reduce their ecological footprints and becoming more livable and equitable places. Among the more than variety of books on these subjects, Tim is the author of Biophilic Cities and the Handbook of Bophilic City Planning & Design. The National Parks Board (NParks) of Singapore is committed to enhancing and managing the urban ecosystems of Singapore’s biophilic City in a Garden. NParks is the lead agency for greenery, biodiversity conservation, and wildlife and animal health, welfare and management. The board also actively engages the community to enhance the quality of Singapore’s living environment. Lena Chan is the Director of the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC), NParks, where she leads a team of 30 officers who are responsible for a diverse range of expertise relevant to biodiversity conservation. -

Illustrated Plans

HOUSING & TRANSPORT N A D M I R A LT Y R O Woodlands Regional Centre A T D E S W W E S A D T O R Y Y T I S Canberra Plaza L H A R U I N M A D A V E N U E 8 9 E U S T N E E D W V A D A A R O O Y S R LT D A N G Woodlands Regional Centre I R M A N A D L D A N O W O A W SEMBAWANG B O M R E S T WOODLANDS H D CANBERRA LINK SEMBAWANG WAY 9 A E - NORTH U E N S O V A O R D S N U L A T Y D H T O O EC L W XO Y A P RR I S R R E H I S CANBERRA I DS U SO E N M W R M A T D A V E N A Y B N E ADMIRALTY U A E C W 8 S E A R N C 7 G U E W N A V E R E L A N D S O O D I KRANJI WAY W O T A O D D E A WOODLANDS 4 KRANJI WAY N D O YISHUN AVENUE 7 A R E O S LIM CHU KANG ROAD KANG CHU LIM R U D N N W A E E I L V T D 3 A O E O MARSILING U S 2 E O N D E E N KRANJI ROAD W V N A U D S A Y W O O D L A N N I L N S H U D E N O RING ROAD O V B O A R 1 U W E U WOODLANDS AVENUE 12 E N T K W O O D L A N D S A V YISHUN H I T - S WOODLANDS SOUTH N Melody Spring @ Yishun WOODLANDS AVE 2 D T O A U YISHUN AVENUE 8 I H S E U O L E T D S R M A A R I E O YISHUN AVENUE 1 KRANJI R V E T W I Y X G A E R N P H I I R D R T H N E L U T S H A O S I C U S R Y E T D E W N N Y I S H U N C E A O A K X Y I R P E D G A R R SUNGEI KADUT STREET 1 YISHUN AVENUE 1 NEO TIEW ROAD N LIM CHU KANG ROAD O I U R E D S S S E O D U S N N D R E A W YI S A V HU RO N RING L A KHATIB D B A E U O L V C T Y I U R F O PUNGGOL POINT R W M A D N D A I T A V SAMUDERA U E K N U D E N MANDAI ROAD I A L K I MANDAI ROAD T E M S TECK LEE A G N E D A N YISHUN AVENUE 1 I W R MANDAI ROAD NIBONG U O A D R S A T E L E SUM KEE -

Apr–Jun 2013

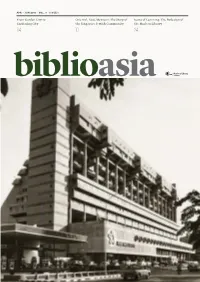

VOL. 9 iSSUe 1 FEATURE APr – jUn 2013 · vOL. 9 · iSSUe 1 From Garden City to Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of Icons of Learning: The Redesign of Gardening City the Singapore Jewish Community the Modern Library 04 10 24 01 BIBLIOASIA APR –JUN 2013 Director’s Column Editorial & Production “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay, argues for the place of women in Managing Editor: Stephanie Pee Editorial Support: Sharon Koh, the literary tradition. The title also makes for an apt underlying theme of this issue Masamah Ahmad, Francis Dorai of BiblioAsia, which explores finding one’s place and space in Singapore. Contributors: Benjamin Towell, With 5.3 million people living in an area of 710 square kilometres, intriguing Bernice Ang, Dan Koh, Joanna Tan, solutions in response to finding space can emerge from sheer necessity. This Juffri Supa’at, Justin Zhuang, Liyana Taha, issue, we celebrate the built environment: the skyscrapers, mosques, synagogues, Noorashikin binte Zulkifli, and of course, libraries, from which stories of dialogue, strife, ambition and Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar, Ten Leu-Jiun Design & Print: Relay Room, Times Printers tradition come through even as each community attempts to find a space of its own and leave a distinct mark on where it has been and hopes to thrive. Please direct all correspondence to: A sense of sanctuary comes to mind in the hubbub of an increasingly densely National Library Board populated city. In Justin Zhuang’s article, “From Garden City to Gardening City”, he 100 Victoria Street #14-01 explores the preservation and the development of the green lungs of Sungei Buloh, National Library Building Singapore 188064 Chek Jawa and, recently, the Rail Corridor, as breathing spaces of the city. -

How to Prepare the Final Version of Your Manuscript for the Proceedings of the 11Th ICRS, July 2007, Ft

Proceedings of the 12th International Coral Reef Symposium, Cairns, Australia, 9-13 July 2012 22A Social, economic and cultural perspectives Conservation of our natural heritage: The Singapore experience Jeffrey Low, Liang Jim Lim National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569 Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract. Singapore is a highly urbanised city-state of approximately 710 km2 with a population of almost 5 million. While large, contiguous natural habitats are uncommon in Singapore, there remains a large pool of biodiversity to be found in its four Nature Reserves, 20 Nature Areas, its numerous parks, and other pockets of naturally vegetated areas. Traditionally, conservation in Singapore focused on terrestrial flora and fauna; recent emphasis has shifted to marine environments, showcased by the reversal of development works on a unique intertidal shore called Chek Jawa (Dec 2001), the legal protection of Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (mangrove and mudflat habitats) and Labrador Nature Reserve (coastal habitat) in 2002, the adoption of a national biodiversity strategy (September 2009) and an integrated coastal management framework (November 2009). Singapore has also adopted the “City in a Garden” concept, a 10-year plan that aims to not only heighten the natural infrastructure of the city, but also to further engage and involve members of the public. The increasing trend of volunteerism, from various sectors of society, has made “citizen-science” an important component in many biodiversity conservation projects, particularly in the marine biodiversity-rich areas. Some of the key outputs from these so-called “3P” (people, public and private) initiatives include confirmation of 12 species of seagrasses in Singapore (out of the Indo-Pacific total of 23), observations of new records of coral reef fish species, long term trends on the state of coral reefs in one of the world's busiest ports, and the initiation of a Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey project. -

Signature Homes by Hiaphoe FY 2010 Calendar of Events January to December 2010

HIAP HOE LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Signature Homes by HiapHoe FY 2010 Calendar of Events January to December 2010 20 January Temporary Occupation Permit obtained for Oxford Suites 28 January Wyndham Group to Operate Hiap Hoe-SuperBowl Hotels at Zhongshan Park in Balestier 11 February 2009 Full Year Financial Statement and Dividend Announcement 26 February Temporary Occupation Permit obtained for Cuscaden Royale 3 March Hiap Hoe Launches Home Resort at Cavenagh 17 March Change of name of wholly-owned subsidiary, Siong Hoe Development Pte Ltd to Hiap Hoe Investment Pte. Ltd. 24 March Listing and quotation of 94,911,028 Bonus Shares 20 April Annual General Meeting / Extraordinary General Meeting 12 May First Quarter Financial Statement Announcement 13 August Second Quarter Financial Statement Announcement 9 November Third Quarter Financial Statement and Dividend Announcement 25 November Book Closure Date - Interim Dividend of 0.25 cents per ordinary share Contents 01 Vision, Mission, Value Corporate Profile 02 Group Structure 03 Financial Highlights 04 Chairman’s Message 06 Financial Review 08 Operations Review 14 Board of Directors 16 Key Management 17 Corporate Information 18 Risk Management For a better understanding of the Annual Report and overall profile of the Company, shareholders are encouraged to download the SGX’s Investor’s Guide Books via this link, http://www.sgx.com/wps/portal/marketplace/mp-en/investor_centre/investor_guide. For more information on the Group, please visit www.hiaphoe.com Vision, Mission, Values A RICHER LIFE FOR each OF US Be a competitive market player in residential properties, bringing reward and satisfaction to shareholders, customers, associates and employees We prize foresight, integrity and commitment among other time- honoured values Company Profile The Hiap Hoe Group has more than three decades of experience in construction industry, and has been responsible for a large and varied number of projects in Singapore. -

NSS Bird Group Report – November 2019

NSS Bird Group Report – November 2019 By Geoff Lim, Alan Owyong (compiler), Tan Gim Cheong (ed.). November was spectacular, with the first record of two species – the Fairy Pitta and Shikra at the Central Catchment Nature Reserve; an Oriental Dwarf Kingfisher (the locally extinct rufous- backed subspecies), found inside a camera shop in the city; and, a rare Red-footed Booby at St John’s Island. Also, it was and has always been a great month to spot migrating raptors in southern Singapore. A Fairy’s Visitation in November The first Fairy Pitta discovered in Singapore on 8 Nov 2019 – photo by Francis Yap. On 8 November 2019, Francis Yap and Richard White were en route to Jelutong Tower, when the duo spotted a paler than usual pitta along the trail under the darkening morning sky as a storm threatened from Sumatra. When Francis managed to regain phone reception and were able to refer to other photos on the internet, the two confirmed that they had Singapore’s first record of the Fairy Pitta, Pitta nympha. Francis’ electrifying account can be accessed here. The Fairy Pitta stopped over for a week, with daily records from 8-13 November 2019. 1 The Fairy Pitta has been recognised as part of a superspecies comprising the Blue-winged Pitta, P. moluccensis, Mangrove Pitta, P. megarhyncha, and Indian Pitta, P. brachyura (Lambert & Woodcock, 1996:162), hence the superficial resemblance with one another. BirdLife has classified the species as Vulnerable, with key threats being habitat loss and conversion, as well as local trapping pressure (BirdLife, 2019). -

NSS Bird Group Report – February 2020

NSS Bird Group Report – February 2020 By Geoff Lim & Isabelle Lee, & Tan Gim Cheong (ed.) February continues with unusual species – the first occurrence of the Chinese Blackbird in Singapore, the first occurrence of the nominate subspecies of the White Wagtail, and our third sighting of the very rare Chinese Blue Flycatcher. Chinese Blue Flycatcher, photographed by a casual birder on 25 February 2020 at the CCNR. The third sighting of the very rare Chinese Blue Flycatcher, Cyornis glaucicomans, was made by a casual birder on 25 February 2020 inside the Central Catchment Nature Reserve (CCNR). On 29 February 2020, the bird was spotted again and heard in the early morning by Geoff Lim and Isabelle Lee, and subsequently seen by several others in the late morning. Previous occurrences for the species included a sighting in November 1997 at Sungei Buloh, and a male bird photographed at Bidadari in November 2013 (the supposed occurrence in December 2015 was a mis-identification). 1 The Chinese Blue Flycatcher was previously lumped together as a subspecies of the Blue-throated Flycatcher, Cyornis rubeculoides, (for more taxonomic info, see Zhang, et al., 2016). Although classified as Least Concern, the bird is generally uncommon and widespread across its breeding range, which extends from southern Shaanxi and western Hubei to Yunnan, and its non-breeding range in west, central and southern Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia (del Hoyo, Collar and Christie, 2020), and Singapore. This species prefers dense thickets, and the low and shady understorey, rarely 3m above the ground (del Hoyo, Collar and Christie, 2020); though observations by volunteers have shown that the species does visit the mid to upper canopy levels of the rainforest.