How to Prepare the Final Version of Your Manuscript for the Proceedings of the 11Th ICRS, July 2007, Ft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing the Museum Roundtable

P. 2 P. 3 Introducing the Hello! Museum Roundtable Singapore has a whole bunch of museums you might not have heard The Museum Roundtable (MR) is a network formed by of and that’s one of the things we the National Heritage Board to support Singapore’s museum-going culture. We believe in the development hope to change with this guide. of a museum community which includes audience, museum practitioners and emerging professionals. We focus on supporting the training of people who work in We’ve featured the (over 50) museums and connecting our members to encourage members of Singapore’s Museum discussion, collaboration and partnership. Roundtable and also what you Our members comprise over 50 public and private can get up to in and around them. museums and galleries spanning the subjects of history and culture, art and design, defence and technology In doing so, we hope to help you and natural science. With them, we hope to build a ILoveMuseums plan a great day out that includes community that champions the role and importance of museums in society. a museum, perhaps even one that you’ve never visited before. Go on, they might surprise you. International Museum Day #museumday “Museums are important means of cultural exchange, enrichment of cultures and development of mutual understanding, cooperation and peace among peoples.” — International Council of Museums (ICOM) On (and around) 18 May each year, the world museum community commemorates International Museum Day (IMD), established in 1977 to spread the word about the icom.museum role of museums in society. Be a part of the celebrations – look out for local IMD events, head to a museum to relax, learn and explore. -

RSG Book PDF Version.Pub

GLOBAL RE-INTRODUCTION PERSPECTIVES Re-introduction case-studies from around the globe Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or any of the funding organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi or Denver Zoological Foundation. Published by: IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group Copyright: © 2008 IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Soorae, P. S. (ed.) (2008) GLOBAL RE-INTRODUCTION PERSPECTIVES: re-introduction case-studies from around the globe. IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group, Abu Dhabi, UAE. viii + 284 pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1113-3 Cover photo: Clockwise starting from top-left: • Formosan salmon stream, Taiwan • Students in Madagascar with tree seedlings • Virgin Islands boa Produced by: IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group Printed by: Abu Dhabi Printing & Publishing Co., Abu Dhabi, UAE Downloadable from: http://www.iucnsscrsg.org (downloads section) Contact Details: Pritpal S. Soorae, Editor & RSG Program Officer E-mail: [email protected] Plants Conservation and re-introduction of the tiger orchid and other native orchids of Singapore Tim Wing Yam Senior Researcher, National Parks Board, Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569 ([email protected]) Introduction Singapore consists of a main island and many offshore islands making up a total land area of more than 680 km2. -

From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories a Floral Tribute to Singapore's Stories

Appendix II From Tales to Legends: Discover Singapore Stories A floral tribute to Singapore's stories Amidst a sea of orchids, the mythical Merlion battles a 10-metre-high “wave” and saves a fishing village from nature’s wrath. Against the backdrop of an undulating green wall, a sorcerer’s evil plan and the mystery of Bukit Timah Hill unfolds. Hidden in a secret garden is the legend of Radin Mas and the enchanting story of a filial princess. In celebration of Singapore’s golden jubilee, 10 local folklore are brought to life through the creative use of orchids and other flowers in “Singapore Stories” – a SG50-commemorative floral display in the Flower Dome at Gardens by the Bay. Designed by award-winning Singaporean landscape architect, Damian Tang, and featuring more than 8,000 orchid plants and flowers, the colourful floral showcase recollects the many tales and legends that surround this city-island. Come discover the stories behind Tanjong Pagar, Redhill, Sisters’ Island, Pulau Ubin, Kusu Island, Sang Nila Utama and the Singapore Stone – as told through the language of plants. Along the way, take a walk down memory lane with scenes from the past that pay tribute to the unsung heroes who helped to build this nation. Date: Friday, 31 July 2015 to Sunday, 13 September 2015 Time: 9am – 9pm* Location: Flower Dome Details: Admission charge to the Flower Dome applies * Extended until 10pm on National Day (9 August) About Damian Tang Damian Tang is a multiple award-winning landscape architect with local and international titles to his name. -

Singapore Science Festival 2013 Opens Bigger and Better

SINGAPORE SCIENCE FESTIVAL 2013 OPENS BIGGER AND BETTER Printable solar-powered batteries, eco-friendly jewellery making workshops, and exploring the extreme frontiers of chemistry are just some of the exciting offerings in store at this year’s Festival SINGAPORE, 19 July 2013 – The Singapore Science Festival 2013 kicks off today with the launch of X-periment!, a weekend science carnival held from July 19th to July 21st, by Guest-of-Honour Mr Lim Chuan Poh, Chairman, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) at the Central Atrium in Marina Square. The Festival, co-sponsored by A*STAR and Science Centre Singapore with marketing partner Cityneon, brings together close to 70 exciting events, activities, and exhibitions island wide, from July 19th to August 4th, featuring world-class speakers and science performers from Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and the United Kingdom. Taglined, ‘Science is Fun’, the nation’s largest annual science event collectively celebrates and showcases science in an attractive, experiential, and relevant manner to everyday life. X-PERIMENT! This year, X-periment! is headlined by internationally renowned science entertainer, Dr Ken Farquhar, who will be performing his ‘Entertaining Science Circus Show’ that demonstrates the science behind some of the common circus feats performed by acrobats across the world. “The Singapore Science Festival is an eagerly anticipated event on our national calendar. This year’s festival is bigger and better and promises to demonstrate how science can be fun through the wide range of events, activities, and exhibitions lined up in the upcoming weeks, including crowd favourites like X-periment!, STAR Lecture, and the Singapore Mini Maker Faire,” said Associate Professor (A/P) Lim Tit Meng, Chief Executive, Science Centre Singapore. -

Insider People · Places · Events · Dining · Nightlife

APRIL · MAY · JUNE SINGAPORE INSIDER PEOPLE · PLACES · EVENTS · DINING · NIGHTLIFE INSIDE: KATONG-JOO CHIAT HOT TABLES CITY MUST-DOS AND MUCH MORE Ready, set, shop! Shopping is one of Singapore’s national pastimes, and you couldn’t have picked a better time to be here in this amazing city if you’re looking to nab some great deals. Score the latest Spring/Summer goods at the annual Fashion Steps Out festival; discover emerging local and regional designers at trade fair Blueprint; or shop up a storm when The Great Singapore Sale (3 June to 14 August) rolls around. At some point, you’ll want to leave the shops and malls for authentic local experiences in Singapore. Well, that’s where we come in – we’ve curated the best and latest of the city in this nifty booklet to make sure you’ll never want to leave town. Whether you have a week to deep dive or a weekend to scratch the surface, you’ll discover Singapore’s secrets at every turn. There are rich cultural experiences, stylish bars, innovative restaurants, authentic local hawkers, incredible landscapes and so much more. Inside, you’ll find a heap of handy guides – from neighbourhood trails to the best eats, drinks and events in Singapore – to help you make the best of your visit to this sunny island. And these aren’t just our top picks: we’ve asked some of the city’s tastemakers and experts to share their favourite haunts (and then some), so you’ll never have a dull moment exploring this beautiful city we call home. -

Singapore | October 17-19, 2019

BIOPHILIC CITIES SUMMIT Singapore | October 17-19, 2019 Page 3 | Agenda Page 5 | Site Visits Page 7 | Speakers Meet the hosts Biophilic Cities partners with cities, scholars and advocates from across the globe to build an understanding of the importance of daily contact with nature as an element of a meaningful urban life, as well as the ethical responsibility that cities have to conserve global nature as shared habitat for non- human life and people. Dr. Tim Beatley is the Founder and Executive Director of Biophilic Cities and the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, in the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, School of Architecture at the University of Virginia. His work focuses on the creative strategies by which cities and towns can bring nature into the daily lives of thier residents, while at the same time fundamentally reduce their ecological footprints and becoming more livable and equitable places. Among the more than variety of books on these subjects, Tim is the author of Biophilic Cities and the Handbook of Bophilic City Planning & Design. The National Parks Board (NParks) of Singapore is committed to enhancing and managing the urban ecosystems of Singapore’s biophilic City in a Garden. NParks is the lead agency for greenery, biodiversity conservation, and wildlife and animal health, welfare and management. The board also actively engages the community to enhance the quality of Singapore’s living environment. Lena Chan is the Director of the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC), NParks, where she leads a team of 30 officers who are responsible for a diverse range of expertise relevant to biodiversity conservation. -

Apr–Jun 2013

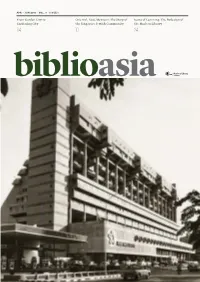

VOL. 9 iSSUe 1 FEATURE APr – jUn 2013 · vOL. 9 · iSSUe 1 From Garden City to Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of Icons of Learning: The Redesign of Gardening City the Singapore Jewish Community the Modern Library 04 10 24 01 BIBLIOASIA APR –JUN 2013 Director’s Column Editorial & Production “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay, argues for the place of women in Managing Editor: Stephanie Pee Editorial Support: Sharon Koh, the literary tradition. The title also makes for an apt underlying theme of this issue Masamah Ahmad, Francis Dorai of BiblioAsia, which explores finding one’s place and space in Singapore. Contributors: Benjamin Towell, With 5.3 million people living in an area of 710 square kilometres, intriguing Bernice Ang, Dan Koh, Joanna Tan, solutions in response to finding space can emerge from sheer necessity. This Juffri Supa’at, Justin Zhuang, Liyana Taha, issue, we celebrate the built environment: the skyscrapers, mosques, synagogues, Noorashikin binte Zulkifli, and of course, libraries, from which stories of dialogue, strife, ambition and Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar, Ten Leu-Jiun Design & Print: Relay Room, Times Printers tradition come through even as each community attempts to find a space of its own and leave a distinct mark on where it has been and hopes to thrive. Please direct all correspondence to: A sense of sanctuary comes to mind in the hubbub of an increasingly densely National Library Board populated city. In Justin Zhuang’s article, “From Garden City to Gardening City”, he 100 Victoria Street #14-01 explores the preservation and the development of the green lungs of Sungei Buloh, National Library Building Singapore 188064 Chek Jawa and, recently, the Rail Corridor, as breathing spaces of the city. -

Two More Therapeutic Gardens Open to Improve Mental Well-Being

Two More Therapeutic Gardens Open to Improve Mental Well-Being With Singapore’s ageing population, the number of dementia-at-risk seniors and persons with dementia is expected to increase. The National Parks Board (NParks) has developed therapeutic gardens in public parks that are not only designed with elderly-friendly features, but also alleviate the onset of dementia through therapeutic horticulture. Seniors enjoying Therapeutic Garden @ Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park On 19 September, NParks opened two new therapeutic gardens in Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park and Tiong Bahru Park. Minister for Health Mr Gan Kim Yong, who was the guest-of-honour, officiated the opening of the two new therapeutic gardens at an event in Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, together with Mr Desmond Lee, Minister for Social and Family Development and Second Minister for National Development. Mr Kenneth Er, CEO of NParks, introducing Therapeutic Garden @ Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park to Minister Gan Kim Yong and Minister Desmond Lee Minister Gan Kim Yong and Minister Desmond Lee touring Therapeutic Garden @ Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park Woh Hup (Private) Limited, one of Singapore’s largest private construction groups, donated $500,000 through the Garden City Fund for the development of the Therapeutic Garden @ Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park and its programmes. NParks will continue to partner with the community to develop a network of therapeutic gardens in parks across Singapore. This includes an upcoming garden in Choa Chu Kang Park which will be completed in 2018. In addition, NParks has developed customised therapeutic horticulture programmes, and will work with eldercare and senior activity centres to conduct these programmes in the therapeutic gardens. -

Singapore for Families Asia Pacificguides™

™ Asia Pacific Guides Singapore for Families A guide to the city's top family attractions and activities Click here to view all our FREE travel eBooks of Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau and Bangkok Introduction Singapore is Southeast Asia's most popular city destination and a great city for families with kids, boasting a wide range of attractions and activities that can be enjoyed by kids and teenagers of all ages. This mini-guide will take you to Singapore's best and most popular family attractions, so you can easily plan your itinerary without having to waste precious holiday time. Index 1. The Singapore River 2 2. The City Centre 3 3. Marina Bay 5 4. Chinatown 7 5. Little India, Kampong Glam (Arab Street) and Bugis 8 6. East Coast 9 7. Changi and Pasir Ris 9 8. Central and North Singapore 10 9. Jurong BirdPark, Chinese Gardens and West Singapore 15 10. Pulau Ubin and the islands of Singapore 18 11. Sentosa, Universal Studios Singapore and "Resorts World" 21 12. Other attractions and activities 25 Rating: = Not bad = Worth trying = A real must try Copyright © 2012 Asia-Pacific Guides Ltd. All rights reserved. 1 Attractions and activities around the Singapore River Name and details What is there to be seen How to get there and what to see next Asian Civilisations Museum As its name suggests, this fantastic Address: 1 Empress Place museum displays the cultures of Asia's Rating: tribes and nations, with emphasis on From Raffles Place MRT Station: Take Exit those groups that actually built the H to Bonham Street and walk to the river Tuesday – Sunday : 9am-7pm (till city-state. -

ST/LIFE/PAGE<LIF-008>

C8 life happenings | THE STRAITS TIMES | FRIDAY, MARCH 13, 2020 | FILMS John Lui Film Correspondent recommends Roll With The Trolls Movie Event Trolls World Tour (2020, PG) is the sequel to the 2016 animated film Picks Trolls. It tells the story of Poppy and Branch, who discover they are from one of six Troll tribes, each dedicated Film to a different genre of music. They set out to unite the tribes as Queen Barb, a member of hard-rock royalty, plans to destroy all other kinds of music. The ticket price includes an activity pack, sand-art activity and chocolate popcorn with marshmallow. WHERE: Cathay Cineplex Parkway Parade, Level 7 Parkway Parade, 80 Marine Parade Road MRT: Eunos WHEN: Tomorrow, 10.30am - 3pm ADMISSION: $15 (single ticket), $58 (family bundle of four tickets) INFO: www.cathaycineplexes.com.sg In The Name Of The Land (PG13) Pierre is 25 when he returns from Wyoming to find Claire, his fiancee, has taken over the family farm. Two decades later, despite the expansion of his farm and family, the accumulated debts and work take a toll on Pierre. The screening will be followed by a live Skype question- and-answer session with French director Edouard Bergeon (nominated for Cesar Awards: Best First Feature Film and Audience Award) and writer Emmanuel Courcol (Ceasefire, 2016; Face Down, 2015). Part of the Francophonie Festival. WHERE: Alliance Francaise, 1 Sarkies Road MRT: Newton WHEN: Wed, 8pm ADMISSION: $15 INFO: alliancefrancaise.org.sg The Lighthouse (M18) From Robert Eggers, the film-maker behind modern horror masterpiece PRINCESS MONONOKE (PG) work, Spirited Away (2001). -

The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Seriesdraws On

Biodiversity: Nature Conservation in the Greening of Singapore - In a small city-state where land is considered a scarce resource, the tension between urban development and biodiversity conservation, which often involves protecting areas of forest from being cleared for development, has always been present. In the years immediately after independence, the Singapore government was more focused on bread-and-butter issues. Biodiversity conservation was generally not high on its list of priorities. More recently, however, the issue of biodiversity conservation has become more prominent in Singapore, both for the government and its citizens. This has predominantly been influenced by regional and international events and trends which have increasingly emphasised the need for countries to show that they are being responsible global citizens in the area of environmental protection. This study documents the evolution of Singapore’s biodiversity conservation efforts and the on-going paradigm shifts in biodiversity conservation as Singapore moves from a Garden City to a City in a Garden. The Singapore Urban Systems Studies Booklet Series draws on original Urban Systems Studies research by the Centre for Liveable Cities, Singapore (CLC) into Singapore’s development over the last half-century. The series is organised around domains such as water, transport, housing, planning, industry and the environment. Developed in close collaboration with relevant government agencies and drawing on exclusive interviews with pioneer leaders, these practitioner-centric booklets present a succinct overview and key principles of Singapore’s development model. Important events, policies, institutions, and laws are also summarised in concise annexes. The booklets are used as course material in CLC’s Leaders in Urban Governance Programme. -

Circle Line Guide

SMRT System Map STOP 4: Pasir Panjang MRT Station Before you know, it’s dinner LEGEND STOP 2: time! Enjoy a sumptuous East West Line EW Interchange Station Holland Village MRT Station meal at the Pasir Panjang North South Line NS Bus Interchange near Station Food Centre, which is just Head two stops down to a stop away and is popular Circle Line CC North South Line Extension Holland Village for lunch. (Under construction) for its BBQ seafood and SMRT Circle Line Bukit Panjang LRT BP With a huge variety of cuisines Malay fare. Stations will open on 14 January 2012 available, you’ll be spoilt for STOP 3: choice of food. Haw Par Villa MRT Station STOP 1: Spend the afternoon at the Haw Botanic Gardens MRT Station Par Villa and immerse in the rich Start the day with some fresh air and Chinese legends and folklore, nice greenery at Singapore Botanic dramatised through more than Gardens. Enjoy nature at its best or 1,000 statues and dioramas have fun with the kids at the Jacob found only in Singapore! Ballas Garden. FAMILY. TIME. OUT. Your Handy Guide to Great Food. Fun Activities. Fascinating Places. One day out on the Circle Line! For Enquiries/Feedback EAT. SHOP. CHILL. SMRT Customer Relations Centre STOP 1: Buona Vista Interchange Station 1800 336 8900 A short walk away and you’ll find 7.30am to 6.30pm STOP 3: yourself at Rochester Park where Mondays – Fridays, except Public Holidays you can choose between a hearty Haw Par Villa MRT Station SMRT Circle Line Quick Facts Or send us an online feedback at American brunch at Graze or dim Venture back west for dinner www.smrt.com.sg/contact_us.asp Total route length: 35.4km Each train has three cars, 148 seats and can take up to 670 sum at the Min Jiang at One-North after a day at the mall.