Masculinity and the Machine Man: Gender in the History of Data Processing Chapter for Gender Codes, Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Processing with Unit Record Equipment in Iceland

Data Processing with Unit Record Equipment in Iceland Óttar Kjartansson (Retired) Manager of Data Processing Department at Skýrr, Iceland [email protected] Abstract. This paper presents an overview of the usage of unit record equipment and punched cards in Iceland and introduces some of the pioneers. The usage of punched cards as a media in file processing started 1949 and became the dominant machine readable media in Iceland until 1968. After that punched cards were still used as data entry media for a while but went completely out of use in 1982. Keywords: Data processing, unit record, punched card, Iceland. 1 Hagstofa Íslands Hagstofa Íslands (Statistical Bureau of Iceland) initiated the use of 80 column punched cards and unit record equipment in Iceland in the year 1949. The first ma- chinery consisted of tabulating machine of the type IBM 285 (handled numbers only), the associated key punch machines, verifiers, and a card sorter. See Figures 1 and 2. This equipment was primarily used to account for the import and export for Iceland. Skýrr (Skýrsluvélar ríkisins og Reykjavíkurborgar - The Icelandic State and Munici- pal Data Center) was established three years later by an initiative from Hagstofa Íslands, Rafmagnsveita Reykjavíkur (Reykjavík Electric Power Utility), and the Medical Director of Health of Iceland as was described in an earlier article [3]. Fig. 1. IBM 285 Electric Accounting Machine at Hagstofa Íslands year 1949 J. Impagliazzo, T. Järvi, and P. Paju (Eds.): HiNC 2, IFIP AICT 303, pp. 225–229, 2009. © IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2009 226 Ó. Kjartansson Fig. 2. Early form of the data registration using a punched card. -

Introduction to Database Systems

CO-560-A Databases and Web Services Instructors: Peter Baumann email: [email protected] office: room 88, Research 1 Databases & Web Services (P. Baumann) 1 Where It All Started Source: Wikipedia . 1890 census on 62,947,714 US population “Big Data” • was announced after only six weeks of processing . Hollerith „tabulating machine and sorter“ . Tabulating Machine Company International Business Machines Corporation Herman Hollerith in 1888 Hollerith card puncher, used by the United States Census Bureau Hollerith punched card Databases & Web Services (P. Baumann) 2 Databases & Web Services (P. Baumann) [image: Intel] 3 What Is „Big Data“? . Internet: the unprecedented . Typical Big Data: information collector • Business Intelligence • 2012: 200m Web servers [Yahoo] • Social networks - Facebook, • estd 50+b static pages [Yahoo] Twitter, GPS, ... • 40 b photos [Facebook] • Life Science: patient data, imagery • 2012: 31b searches/m [Google] • Geo: Satellite imagery, weather . 2025: 463 Exabytes / day data, crowdsourcing, ... Data = the „new gold“, „new oil“ Petrol industry: „more bytes than barrels“ Databases & Web Services (P. Baumann) 4 Today: „Data Deluge“ . „It is estimated that a week„s work at the New York Times contains more information than a person in the 18th Century would encounter in their entire lifetime and the thought is that within 10 years the rate of information doubling will occur every 72 hours.“ -- P. „Bud“ Peterson, U Colorado . “global mobile data traffic 597 petabytes per month in 2011 (8x the size of the entire global Internet in 2000) estimated to grow to 6,254 petabytes per month by 2015” -- Forbes, June 2012 . a typical new car has about 100 million lines of code • -- http://www.wired.com/autopia/2012/12/automotive-os-war/ Databases & Web Services (P. -

Herman Hollerith and Early Mechanical/Electrical Tabulator/Sorters

Herman Hollerith and early mechanical/electrical tabulator/sorters The US Constitution requires that the people of the U.S. be counted every ten years and that the members of the House of Representatives “be apportioned among the States according to their respective numbers”1. (The other house of Congress, the Senate, has two members from each state.) Accordingly, every ten years, a census is taken. By 1880, the census was becoming harder and harder to accomplish. Everything was done on paper. Marks were placed in squares on paper, the marked squares were counted, and of course people made many mistakes. Further, the census was used more and more not just to count people but to get useful data on age, gender, marital status, working status, and so on. There were more and more marks to make and count! Herman Hollerith: the inventor of mechanical/electrical data processing systems Herman Hollerith graduated from the Columbia University School of Mines (in New York City) in 1879 at the age of 19. He knew about the problems with the census and be- gan research into mechanizing part of the counting of the census. In 1882, he taught me- chanical engineering at MIT and conducted his first experiments with punched cards. He was extremely successful, and he soon moved to Washington D.C. and set up a company, The Hollerith Electric Tabulating System. By the middle of the 1880’s, his first punched-card system was working. His company provided the Census Office with the equipment used in processing the 1890 census —62 million punched cards were processed by his machines, cutting two years off the time to complete the census. -

Punched Card - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 11

.... _ ALL COMMUNICATIONS IN REFERENCE TO FORESTRY TO BE ADDRESSED TO THE CHIEF FORESTER VICTORIA. B.C. TIlE GO'IEIltDIEIIT Of THE P/IOVJII!;E DfBRItISH CIIJIIIIA DEPARTMENT OF LANDS FOREST BRANCH Yay 16th, 1928. H. J. Coles, Esq., Port Alberni, B.C. Please refer to File No. Management 081406 Dear Sirl- This is to advise that you passed the Licensed Scaler's Examina- tion held by Mr. A. L. Bryant a.t Vancouver, B.C., on May 2nd and 3rd, 1928. Your ~cence No. 811 is enclosed herewith. Xours truly, JM/pb • 1 Enc.l• N° 811 lHE 60VERNMIJIT OF '(f£ PROVINCe OF BRlnsH CIl.UIBIA FOREST ACT AND AMENDMENTS. ~raliug mirturt. FOREST BRANCH, LANDS DEPARTtvt~_NT. r)//) -4 ««e/<i;««<<<</tJ<<<<< < «««<<<<<<<<<<<<<<.<<. 192.K. .. W41n 1n tn (!1rrtify thatC~. /~~J.(~ff/~ -z::.~l::k~ -r1J->·r /7' £I P' . ;j residing at./!&~ L.1~~~-t.- Yi...-£" ~ ~ . ", in the Province of British Columbia, ;;.«~ ~ d-1~ ed ;22 2. / q "'r 8::. b has been examin /07 .••• =Zf'7;m .m.' mm.. .... ... m.................... /~ ..... .... ......... y •••• ««««<<<<<... - «««««< <(.,"F«<· < «. «<.««< of the Board of Examiners for Licensing alers, as provided in the "Forest Act" and amendments, and having creditably passed the said examination is hereby appointed a Licensed Scaler, and ·is duly authorized to perform the duties of a Licensed Scaler, as specified under Part VIII. of the "Forest <~:<~,.(_2.,_,;,::c,.(. «c.,"G~~< .. .. < ••• «« ••• «<•• CHAIRMAN OF BOARD OF EXAMINERS. Punched card - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 11 Punched card From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A punched card (or punch card or Hollerith card or IBM card) is a piece of stiff paper that contains digital information represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. -

2 9215FQ14 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Category Pages Facilities & Buildings 3-10 General Reference 11-20 Human Resources

2 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Category Pages Facilities & Buildings 3-10 General Reference 11-20 Human Resources 21-22 Legal 23-25 Marketing 26 Personal Names (Individuals) 27 Predecessor Companies 28-29 Products & Services 30-89 Public Relations 90 Research 91-97 April 10, 2007 9215FQ14 3 Facilities & Buildings Q. When did IBM first open its offices in my town? A. While it is not possible for us to provide such information for each and every office facility throughout the world, the following listing provides the date IBM offices were established in more than 300 U.S. and international locations: Adelaide, Australia 1914 Akron, Ohio 1917 Albany, New York 1919 Albuquerque, New Mexico 1940 Alexandria, Egypt 1934 Algiers, Algeria 1932 Altoona, Pennsylvania 1915 Amsterdam, Netherlands 1914 Anchorage, Alaska 1947 Ankara, Turkey 1935 Asheville, North Carolina 1946 Asuncion, Paraguay 1941 Athens, Greece 1935 Atlanta, Georgia 1914 Aurora, Illinois 1946 Austin, Texas 1937 Baghdad, Iraq 1947 Baltimore, Maryland 1915 Bangor, Maine 1946 Barcelona, Spain 1923 Barranquilla, Colombia 1946 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 1938 Beaumont, Texas 1946 Belgrade, Yugoslavia 1926 Belo Horizonte, Brazil 1934 Bergen, Norway 1946 Berlin, Germany 1914 (prior to) Bethlehem, Pennsylvania 1938 Beyrouth, Lebanon 1947 Bilbao, Spain 1946 Birmingham, Alabama 1919 Birmingham, England 1930 Bogota, Colombia 1931 Boise, Idaho 1948 Bordeaux, France 1932 Boston, Massachusetts 1914 Brantford, Ontario 1947 Bremen, Germany 1938 9215FQ14 4 Bridgeport, Connecticut 1919 Brisbane, Australia -

The Development of Punch Card Tabulation in the Bureau of the Census

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world’s books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that’s often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book’s long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google’s system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

House for the History of IBM Data Processing

House for the History of IBM Data Processing Hollerith Electric Tabulating System / 1890 (Replica made by Club Members in 1997) Herman Hollerith (1860-1929) House for the History of IBM Data Processing Purpose • Demonstrating the history of IBM‘s data processing efforts, ranging from Hollerith (1890) through the Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen Gesellschaft (DEHOMAG, 1910 -1949) up to 1995. • Presenting information about the achievements IBM accomplished as Data Processing Pioneer and 71063 Sindelfingen (Germany) Establisher of a German Technology Center Bahnhofstr. 43 (at corner Neckarstr.) (Production and Research) E-Mail: [email protected] Activities of the Club Members Tel.: 049-(0)7031 - 41 51 08 • Conducting guided tours • Maintaining the installed machines • Completing the Collection of Historical IBM Equipment Parking behind the building (approach from Neckarstr.) The exhibited Systems, Machines and Devices are restored and workable. DEHOMAG Tabulator D 11/ 1935 IBM 1401 Data Processing System / 1959 with Summary Punch (from 1950s) with Magnetic Tapes, IBM 1403 Printer, IBM 1311 Disks Data processing started with the Punched Card System invented Electronic data processing started in the USA in the early 1950s, and developed by Herman Hollerith to a working product during with Germany following not much later. At first, the large enter- the years 1882 to 1890. The first successful application of the prises took advantage of the new possibilities offered by electronic Hollerith Electric Tabulating System occurred during the US data processing. Census of 1890. (processing 62.5 Million cards) Towards the end of the 1950s the transistor technology The first large-scale commercial application was began in 1895 provided an increase in processing speed. -

History and Evolution of IBM Mainframes Over the 60 Years Of

History and Evolution of IBM Mainframes over SHARE’s 60 Years Jim Elliott – z Systems Consultant, zChampion, Linux Ambassador IBM Systems, IBM Canada ltd. 1 2015-08-12 © 2015 IBM Corporation Reports of the death of the mainframe were premature . “I predict that the last mainframe will be unplugged on March 15, 1996.” – Stewart Alsop, March 1991 . “It’s clear that corporate customers still like to have centrally controlled, very predictable, reliable computing systems – exactly the kind of systems that IBM specializes in.” – Stewart Alsop, February 2002 Source: IBM Annual Report 2001 2 2015-08-12 History and Evolution of IBM Mainframes over SHARE's 60 Years © 2015 IBM Corporation In the Beginning The First Two Generations © 2015 IBM Corporation Well, maybe a little before … . The Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company in 1911 – Tabulating Machine Company – International Time Recording Company – Computing Scale Company of America – Bundy Manufacturing Company . Tom Watson, Sr. joined in 1915 . International Business Machines – 1917 – International Business Machines Co. Limited in Toronto, Canada – 1924 – International Business Machines Corporation in NY, NY Source: IBM Archives 5 2015-08-12 History and Evolution of IBM Mainframes over SHARE's 60 Years © 2015 IBM Corporation The family tree – 1952 to 1964 . Plotting the family tree of IBM’s “mainframe” computers might not be as complicated or vast a task as charting the multi-century evolution of families but it nevertheless requires far more than a simple linear diagram . Back around 1964, in what were still the formative years of computers, an IBM artist attempted to draw such a chart, beginning with the IBM 701 of 1952 and its follow-ons, for just a 12-year period . -

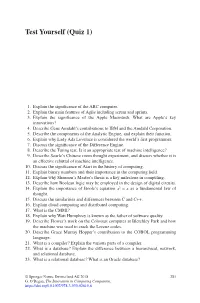

Test Yourself (Quiz 1)

Test Yourself (Quiz 1) 1. Explain the significance of the ABC computer. 2. Explain the main features of Agile including scrum and sprints. 3. Explain the significance of the Apple Macintosh. What are Apple’s key innovations? 4. Describe Gene Amdahl’s contributions to IBM and the Amdahl Corporation. 5. Describe the components of the Analytic Engine, and explain their function. 6. Explain why Lady Ada Lovelace is considered the world’s first programmer. 7. Discuss the significance of the Difference Engine. 8. Describe the Turing test. Is it an appropriate test of machine intelligence? 9. Describe Searle’s Chinese room thought experiment, and discuss whether it is an effective rebuttal of machine intelligence. 10. Discuss the significance of Atari in the history of computing. 11. Explain binary numbers and their importance in the computing field. 12. Explain why Shannon’s Master’s thesis is a key milestone in computing. 13. Describe how Boolean logic may be employed in the design of digital circuits. 14. Explain the importance of Boole’s equation x2 = x as a fundamental law of thought. 15. Discuss the similarities and differences between C and C++. 16. Explain cloud computing and distributed computing. 17. What is the CMMI? 18. Explain why Watt Humphrey is known as the father of software quality. 19. Describe Flower’s work on the Colossus computer at Bletchley Park and how the machine was used to crack the Lorenz codes. 20. Describe Grace Murray Hopper’s contribution to the COBOL programming language. 21. What is a compiler? Explain the various parts of a compiler. -

Early History of Computers: Machines for Mass Calculation

Early History of Computers: Machines for Mass Calculation Waseda University, SILS, Science, Technology and Society (LE202) The control revolution • We often think of computers as increasing individual freedoms and liberties. The first computers, however, were associated with the needs of administrators to calculate and control. • The massive technological systems of the modern world led to a crisis of control and the electronic computer was used as a way of handling this situation. • The early drive for computing was largely funded and motivated by military, statebuilding and corporate needs. • The early images of computers in popular culture and science fiction are always of large machines associated with power and control. (There were no personal computers in science fiction novels or movies before the 1970s.) Before electronic computers • There were counting boards of various kinds in most ancient and medieval cultures (abacus, soroban, etc.). • In the early modern period, Pascal, Leibniz and others developed analog calculators. • The most advanced analog (mechanical) calculators were designed by Charles Babbage (1791–1871), but never built. • In the early 20th century, a “computer” meant a person Babbage’s Difference Engine (usually a woman) who carried out calculations. Punch cards • The rise of mass production and mass distribution around the turn of the 20th cenury gave rise to a crisis of control. • This lead to new techniques of data processing and bureaucratic management. • There were a number of different types of machines that were used to deal with this crisis but the most common was the punch card machine. • These consisted of analog computers and electric tabulators that could process around 10,000 punch cards a month. -

Relational Database Systems 1

Relational Database Systems 1 Christoph Lofi Simon Barthel Institut für Informationssysteme Technische Universität Braunschweig www.ifis.cs.tu-bs.de 0. Organizational Issues • Who is who ? – Christoph Lofi • lecture, exams – Simon Barthel • detours, tutorial – Jan-Christoph Kalo • SQL Lab – Regine Dalkiran • office • In case of questions, feel free to ask us. Relational Database Systems 1 – Christoph Lofi – Technische Universität Braunschweig 2 0. Organizational Issues • Lecture – October 23, 2014 to February 5, 2015 – 15:00 – 17:30 (including a break) – integrated lecture (theory, and detours) – 5 credits • Homework – weekly assignments • … can be downloaded from our website / studip • … must be completed in groups of two students Relational Database Systems 1 – Christoph Lofi – Technische Universität Braunschweig 3 0. Organizational Issues • Tutorial groups – led by our Hiwis – homework discussion – Discussion of SQL-lab • In order to pass this module you need to 1) … achieve 50% of homework points (Studienleistung, ungraded 1 CP) 2) … pass the exam (Prüfungsleistung, graded 4 CP) Relational Database Systems 1 – Christoph Lofi – Technische Universität Braunschweig 4 0 Homework • Weekly homework assignments – can be downloaded from our website • From Stud.ip • http://www.ifis.cs.tu-bs.de/teaching/ws-1415/rdb1 • Homework has to be completed within groups of two students (no larger groups, please!) • To be handed in before the next lecture – drop your homework into the mailbox at our institute (Informatikzentrum, 2nd floor) – or just give -

Co-Evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction Between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries Jo A

Co-evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction Between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries Jo Anne Yates WP#3575-93 Revised October 1993 Co-evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries JoAnne Yates Sloan School of Management MIT E52-545 50 Memorial Drive Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-7157 [email protected] Sloan School Working Paper #3575-93 Center for Coordination Science Working Paper #145 October 1993 Accepted for publication in Business History Review ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful to Martin Campbell-Kelly, Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Glenn Porter, Philip Scranton, Eric von Hippel and two anonymous reviewers of the Business History Review for comments on earlier versions of this paper. I appreciate the able assistance of Daniel May and the library staff at the Metropolitan Life Archives, and of Michael Nash, Margery McNinch, and the staff of the Hagley Museum and Library. This research has been generously supported by the Center for Coordination Science, by the MIT Sloan School of Management, and by the Hagley Museum and Library. Co-evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use: Interaction between the Life Insurance and Tabulating Industries In 1890, at the invitation of inventor Herman Hollerith, 25 members of the Actuarial Society of America attended a demonstration of a new type of information-handling equipment: the punched-card tabulator. According to a news account of the meeting, the life insurance actuaries attended because "Any labor-saving device that can be used in the preparation of tabular statements is of interest to actuaries." l Their interest was justified by the magnitude of the information- handling tasks faced by their life insurance firms.