Front of Neck Access to the Airway: a Narrative Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Update

Summer 2016 Clinical Update We are pleased to offer this archive of our award-winning newsletter Clinical Update. There are 75 issues in this document. Each issue has a feature article, summaries of articles in the nursing literature, and Web sites of interest. By downloading and using this archive, you agree that older medical articles may no longer describe appropriate practice. The issues are organized in date order from most recent to oldest. The following pages offer tips on how to navigate the issues and search the archive in Adobe Acrobat Reader. In 2006, we were honored to receive the Will Solimine Award of Excellence in Medical Writing from the American Medical Writers Association, New England Chapter. Issues that received the most positive response over the years include: • Nurses Removing Chest Tubes, a discussion of state boards of nursing’s approaches to this extended practice for registered nurses • Medical Adhesive Safety, a review of guidelines published by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, complete with original tables identifying characteristics of each type of medical tape and how tape components contribute to medical adhesive- related skin injury (MARSI) • Autotransfusion for Jehovah’s Witness Patients, an explanation of the Biblical origins of the reasons for refusing blood transfusion and how continuous autotransfusion may offer an option that is acceptable to members of the faith • Air Transport for Patients with Chest Tubes and Pneumothorax and Chest Drainage and Hyperbaric Medicine, in which each issue provides a thorough analysis of how pressure changes with altitude and with increased atmospheric pressure affect chest drainage and untreated pneumothorax • Age Appropriate Competencies: Caring for Children that describes developmental stages and strategies to deal with a child’s fears at each stage Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Author: Patricia Carroll RN-BC, RRT, MS Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

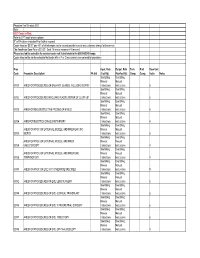

Annex 2. List of Procedure Case Rates (Revision 2.0)

ANNEX 2. LIST OF PROCEDURE CASE RATES (REVISION 2.0) FIRST CASE RATE RVS CODE DESCRIPTION Health Care Case Rate Professional Fee Institution Fee Integumentary System Skin, Subcutaneous and Accessory Structures Incision and Drainage Incision and drainage of abscess (e.g., carbuncle, suppurative hidradenitis, 10060 3,640 840 2,800 cutaneous or subcutaneous abscess, cyst, furuncle, or paronychia) 10080 Incision and drainage of pilonidal cyst 3,640 840 2,800 10120 Incision and removal of foreign body, subcutaneous tissues 3,640 840 2,800 10140 Incision and drainage of hematoma, seroma, or fluid collection 3,640 840 2,800 10160 Puncture aspiration of abscess, hematoma, bulla, or cyst 3,640 840 2,800 10180 Incision and drainage, complex, postoperative wound infection 5,560 1,260 4,300 Excision - Debridement 11000 Debridement of extensive eczematous or infected skin 10,540 5,040 5,500 Debridement including removal of foreign material associated w/ open 11010 10,540 5,040 5,500 fracture(s) and/or dislocation(s); skin and subcutaneous tissues Debridement including removal of foreign material associated w/ open 11011 fracture(s) and/or dislocation(s); skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle fascia, 11,980 5,880 6,100 and muscle Debridement including removal of foreign material associated w/ open 11012 fracture(s) and/or dislocation(s); skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle fascia, 12,120 6,720 5,400 muscle, and bone 11040 Debridement; skin, partial thickness 3,640 840 2,800 11041 Debridement; skin, full thickness 3,640 840 2,800 11042 Debridement; skin, and -

Trinity Ems System Skills Procedures

Procedures 12 Lead EKG Procedure 01 Cardioversion Procedure 28 Airway: BPAP Procedure 02 Chest Decompression Needle Procedure 29 Airway: CPAP Procedure 03 Chest Tube Maintenance Procedure 30 Airway: End-Tidal CO2 Procedure 04 Childbirth Procedure 31 Airway: ETT Introducer (Bougie) Procedure 05 Decontamination Procedure 32 Airway: Foreign Body Obstruction Procedure 06 Airway: Intubation Nasotracheal Procedure 07 Defibrillation: Automated Airway: Intubation Orotracheal Procedure 08 External Defibrillator (AED) Procedure 33 Defibrillation: Manual Procedure 34 Airway: King LTD Procedure 09 Airway: Nebulizer Inhalation EKG Monitoring Procedure 35 Therapy Procedure 10 Impedance Threshold Device (ITD) Procedure 36 Airway: Rapid Sequence Intubation Procedure 11 Injections: Subcutaneous Airway: Respirator Operation Procedure 12 and intramuscular Procedure 37 Airway: Suctioning – Advanced Procedure 13 Intranasal Medication Airway: Suctioning – Basic Procedure 14 Airway: Surgical Cricothyrotomy Procedure 15 Administration Procedure 38 Airway: Tracheostomy Tube Change Procedure 16 Pulse Oximetry Procedure 39 Airway: Ventilator Operation Procedure 17 Restraints: Physical/Chemical Procedure 40 Arterial Line Maintenance Procedure 18 Spinal Examination Procedure 41 Assessment: Adult Procedure 19 Spinal Immobilization Procedure 42 Assessment: Pain Procedure 20 Splinting Procedure 43 Assessment Pediatric Procedure 21 Stroke Screen: (Cincinnati Blood Glucose Analysis Procedure 22 Pre-hospital) Procedure 44 Capnography Procedure 23 Cardiac: External Pacing -

Conversion of Emergent Cricothyrotomy to Tracheotomy in Trauma Patients

REVIEW ARTICLE Conversion of Emergent Cricothyrotomy to Tracheotomy in Trauma Patients Peep Talving, MD, PhD; Joseph DuBose, MD; Kenji Inaba, MD; Demetrios Demetriades, MD, PhD Objectives: To review the literature to determine the patients for whom cricothyrotomy was performed, in- rates of airway stenosis after cricothyrotomy, particu- cluding 368 trauma patients who underwent emergent larly as they compare with previously documented rates cricothyrotomy. The rate of chronic subglottic stenosis of this complication after tracheotomy, and to examine among survivors after cricothyrotomy was 2.2% (11/ the complications associated with conversion. 511) overall and 1.1% (4/368) among trauma patients for follow-up periods with a range from 2 to 60 months. Only Data Sources: We conducted a review of the medical 1 (0.27%) of the 368 trauma patients in whom an emer- literature by the use of PubMed and OVID MEDLINE da- gent cricothyrotomy was performed required surgical tabases. treatment for chronic subglottic stenosis. Although the literature that documents complications of surgical air- Study Selection: We identified all published series that way conversion is scarce, rates of severe complications describe the use of cricothyrotomy, with the inclusion of up to 43% were reported. of the subset of patients who require an emergency air- way after trauma, from January 1, 1978, to January 1, Conclusions: Cricothyrotomy after trauma is safe for ini- 2008. tial airway access among patients who require the estab- lishment of an emergent airway. The prolonged use of a Data Extraction: Only 20 published series of crico- cricothyrotomy tube, however, remains controversial. Al- thyrotomy were identified: 17 retrospective reports and though no study to date has demonstrated any benefit 3 prospective, observational series. -

Surgical Management of Laryngotracheal Stenosis in Adults

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Serveur académique lausannois Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol (2005) 262: 609–615 DOI 10.1007/s00405-004-0887-9 LARYNGOLOGY Mercy George Æ Florian Lang Æ Philippe Pasche Philippe Monnier Surgical management of laryngotracheal stenosis in adults Received: 22 July 2004 / Accepted: 18 October 2004 / Published online: 25 January 2005 Ó Springer-Verlag 2005 Abstract The purpose was to evaluate the outcome fol- the efficacy and reliability of this approach towards the lowing the surgical management of a consecutive series management of laryngotracheal stenosis of varied eti- of 26 adult patients with laryngotracheal stenosis of ologies. Similar to data in the literature, post-intubation varied etiologies in a tertiary care center. Of the 83 pa- injury was the leading cause of stenosis in our series. A tients who underwent surgery for laryngotracheal ste- resection length of up to 6 cm with laryngeal release nosis in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and procedures (when necessary) was found to be technically Head and Neck Surgery, University Hospital of Lau- feasible. sanne, Switzerland, between 1995 and 2003, 26 patients were adults (‡16 years) and formed the group that was Keywords Laryngotracheal stenosis Æ Laryngotracheal the focus of this study. The stenosis involved the trachea resection Æ Anastomosis (20), subglottis (1), subglottis and trachea (2), glottis and subglottis (1) and glottis, subglottis and trachea (2). The etiology of the stenosis was post-intubation injury (n =20), infiltration of the trachea by thyroid tumor (n Introduction =3), seeding from a laryngeal tumor at the site of the tracheostoma (n =1), idiopathic progressive subglottic In the majority of patients, acquired stenosis of the sub- stenosis (n =1) and external laryngeal trauma (n =1). -

Aeromedical Evacuation Springer New York Berlin Heidelberg Hong Kong London Milan Paris Tokyo William W

Aeromedical Evacuation Springer New York Berlin Heidelberg Hong Kong London Milan Paris Tokyo William W. Hurd, MD, MS, FACOG Nicholas J. Thompson Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Wright State University School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio; Col, USAFR, MC, FS, Commander, 445th Aeromedical Staging Squadron, Wright-Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio John G. Jernigan, MD Brig Gen, USAF, CFS (ret), Formerly Commander, Human Systems Center, Brooks AFB, San Antonio, Texas Editors Aeromedical Evacuation Management of Acute and Stabilized Patients Foreword by Paul K. Carlton, Jr., MD Lt Gen, USAF, MC, CFS USAF Surgeon General With 122 Illustrations 1 3 William W. Hurd, MD, MS John G. Jernigan, MD Nicholas J. Thompson Professor and Chair Brig Gen, USAF, CFS (ret) Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Formerly Commander Wright State University School of Medicine Human Systems Center Dayton, OH, USA Brooks AFB Col, USAFR, MC, FS San Antonio, TX, USA Commander 445th Aeromedical Staging Squadron Wright-Patterson AFB Dayton, OH, USA Cover illustration: Litter bearers carry a patient up the ramp of a C-9 Nightingale medical transport aircraft. (US Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Gary R. Coppage). (Figure 7.4 in text) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aeromedical evacuation : management of acute and stabilized patients / [edited by] William W. Hurd, John G. Jernigan. p. ; cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-387-98604-9 (h/c : alk. paper) 1. Airplane ambulances. 2. Emergency medical services. I. Hurd, William W. II. Jernigan, John J. [DNLM: 1. Air Ambulances. 2. Emergency Medical Services. 3. Rescue Work. WX 215 A252 2002] RA996.5 .A325 2002 616.02¢5—dc21 2002021045 ISBN 0-387-98604-9 Printed on acid-free paper. -

Firstcare Assistant Surgeon Reimbursment Policy

1 Retired: 3/31/2019 Effective Date: 10/01/2015 Reimbursement Clinical Guidelines: Assistant Surgeon Reimbursement Policy Position This reimbursement policy applies to FirstCare Health Plans’ Commercial (HMO, PPO, SF) assistant surgeons. Assures assistant surgeon claims reimburse appropriately according to medical necessity guidelines and the member’s health benefit plan. Marketplace (ACA) and Medicare health plans follow Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) guidelines. All Firstcare health plans follow the MCG Assistant Surgeon Guidelines 22nd Edition: The tables (below) replicate the Assistant Surgeon Guidelines information include in the Inpatient and Surgical Care guidelines, 22nd edition. Service codes that are not not included are not reimbursable. Surgical assistant services are idenitifed by adding one of the following modifiers: AS Physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or clinical nurse specialist services for assistant 80 Assistant Surgeon 81 Minimum Assistant Surgeon 82 Assistant Surgeon (when qualified resident surgeon not available) Disclaimer FirstCare has developed coding and reimbursement policies (“Reimbursement Policies”) to provide ready access and general guidance on payment methodologies for medical, surgical and behavioral health services. These policies are subject to all terms of the Provider Service Agreement as well as changes, updates and other requirements of Reimbursement Policies. All Reimbursement Policies are also subject to federal HIPAA rules, and in the case of medical code sets (HCPCS, CPT, ICD-10), FirstCare accepts codes valid for the date of service. Additionally, Reimbursement Policies supplement certain standard FirstCare benefit plans and aid in administering benefits. Thus, federal and state law, contract language, etc. take precedence over the Reimbursement Policies (e.g., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] National Coverage Determinations [NCDs], Local Coverage Determinations [LCDs] or other published documents). -

Introduction

Introduction Pursuant to Mississippi Code Annotated (MCA), section 71-3-15(3)(Rev. 2000), the following Fee Schedule, including Cost Containment and Utilization Management rules and guidelines, is hereby established in order to implement a medical cost containment program. This Fee Schedule, and accompanying rules and guidelines, applies to medical services rendered after the effective date of August 1, 2008, July 1, 2010, and, in the case of inpatient treatment, to services where the discharge date is on or after August 1, 2008 July 1, 2010. This Fee Schedule establishes the maximum level of medical and surgical reimbursement for the treatment of work-related injuries and/or illnesses, which the Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Commission deems to be fair and reasonable. This Fee Schedule shall be used by the Workers’ Compensation Commission, insurance payers, and self- insurers for approving and paying medical charges of physicians, surgeons, and other health care providers for services rendered under the Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Law. This Fee Schedule applies to all medical services provided to injured workers by physicians, and also covers other medical services arranged for by a physician. In practical terms, this means professional services provided by hospital-employed physicians, as well as those physicians practicing independently, are reimbursed under this Fee Schedule. The Commission will require the use of the most current version of the CPT book and HCPCS codes and modifiers in effect at the time services are rendered. All coding, billing and other issues, including disputes, associated with a claim, shall be determined in accordance with the CPT rules and guidelines in effect at the time service is rendered, unless otherwise provided in this Fee Schedule or by the Commission. -

Physician Fee Schedule 2021 Note

Physician Fee Schedule 2021 Note: 2021 Codes in Red; Refer to CPT book for descriptions R" in PA column indicates Prior Auth is required Codes listed as '$0.00" pay 45% of billed amount not to exceed provider’s usual and customary charge for the service The Anesthesia Base Rate is $15.20. Each 15 minute increment=1 time unit. Please use lab fee schedule for covered codes not listed below in the 80000-89249 range. Codes listed on the lab fee schedule that begin with a P or Q are currently non-covered for physicians Proc Inpat. Rate Outpat. Rate Tech. Prof. Base Unit Code Procedure Description PA Ind (Facility) (NonFacility) Comp. Comp. Value Notes See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00100 ANES FOR PROCEDURES ON SALIVARY GLANDS, INCLUDING BIOPSY Instructions Instructions 5 See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00102 ANES FOR PROCEDURES INVOLVING PLASTIC REPAIR OF CLEFT LIP Instructions Instructions 6 See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00103 ANES FOR RECONSTRUCTIVE PROCED OF EYELID Instructions Instructions 5 See Billing See Billing Manual Manual 00104 ANES FOR ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY Instructions Instructions 4 See Billing See Billing ANES FOR PROC ON EXTERNAL, MIDDLE, AND INNER EAR ,INC Manual Manual 00120 BIOPSY Instructions Instructions 5 See Billing See Billing ANES FOR PROC ON EXTERNAL, MIDDLE, AND INNER Manual Manual 00124 EAR,OTOSCOPY Instructions Instructions 4 See Billing See Billing ANES FOR PROC ON EXTERNAL, MIDDLE, AND INNER EAR, Manual Manual 00126 TYMPANOTOMY Instructions Instructions 4 See Billing See Billing Manual -

1 Chapter 111: Chronic Aspiration David W. Eisele the Three Major Functions of the Larynx

Chapter 111: Chronic Aspiration David W. Eisele The three major functions of the larynx - respiration, phonation, and airway production - are all intimately related. Impaired laryngeal protective function can result in aspiration. Aspiration is defined as the laryngeal penetration of secretions, such as saliva, ingested liquids or solids, or reflux of gastric contents, below the level of the true vocal cords. A certain amount of aspiration is known to occur normally. Evaluation of normal humans during sleep by scintigraphy reveals aspiration in nearly one half of those evaluated (Huxley et al, 1978). A certain amount of aspiration may be tolerated without complications provided clearance is normal and defense mechanisms are intact. The contamination of the respiratory tract associated with aspiration can result in a spectrum of bronchopulmonary complications. The severity of complications depends on the volume and the character, such as the pH, of the aspirated material. Respiratory complications of aspiration include bronchospasm, airway obstruction, tracheitis, bronchitis, pneumonia, pulmonary abscess, sepsis, and death (Awe et al, 1966; Bartlett and Gorbach, 1975; Cameron and Zuidema, 1972). Significant aspiration results in a high rate of mortality (Cameron et al, 1973a). Aspiration may be an isolated event related to temporary impairment of normal swallowing mechanisms and airway protection, which may secondary to temporary neurologic dysfunction such as with a depressed state of consciousness related to drugs, alcohol, or metabolic derangement. In addition, seizure, injury, or infection may cause isolated aspiration. Elderly patients are more likely to experience aspiration, presumably related to physiologic and neurologic changes associated with age (Blitzer, 1990). Patients with dentures experience impairment of the oral phase of swallowing with decreased oral sensation and oral control, which may contribute to aspiration. -

Resident Manual of Trauma to the Face, Head, and Neck

Resident Manual of Trauma to the Face, Head, and Neck First Edition ©2012 All materials in this eBook are copyrighted by the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, 1650 Diagonal Road, Alexandria, VA 22314-2857, and are strictly prohibited to be used for any purpose without prior express written authorizations from the American Academy of Otolaryngology— Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. All rights reserved. For more information, visit our website at www.entnet.org. eBook Format: First Edition 2012. ISBN: 978-0-615-64912-2 Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................16 Acknowledgments .............................................................................................18 Resident Trauma Manual Authors ...............................................................19 Chapter 1: Patient Assessment ......................................................................21 I. Diagnostic Evaluations ........................................................................21 A. Full-Body Trauma Assessment ....................................................21 B. History ...............................................................................................22 C. Head and Neck Examination........................................................24 1. Upper Third ................................................................................24 2. Middle Third ...............................................................................24 -

2020 Compilation of Inpatient Only Lists by Specialty

2020 Compilation of Inpatient Only Lists by Specialty Designed for CPT Searching 2020 Bariatric Surgery: Is the Surgery Medicare Inpatient Only or not? Disclaimer: This is not the CMS Inpatient Only Procedure List (Annual OPPS Addendum E). No guarantee can be made of the accuracy of this information which was compiled from public sources. CPT Codes are property of the AMA and are made available to the public only for non-commercial usage. Gastric Bypass or Partial Gastrectomy Procedures Inpatient Only Procedure Not an Inpatient Only Procedure 43644 Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive 43659 Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, stomach procedure; with gastric bypass and Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy (roux limb 150 cm or less) 43645 Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; with gastric bypass and small intestine reconstruction to limit absorption 43775 Laparoscopy, surgical, gastric restrictive procedure; longitudinal gastrectomy (ie, sleeve gastrectomy) 43843 Gastric restrictive procedure, without gastric bypass, for morbid obesity; other than vertical- banded gastroplasty 43845 Gastric restrictive procedure with partial gastrectomy, pylorus-preserving duodenoileostomy and ileoileostomy (50 to 100 cm common channel) to limit absorption (biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch) 43846 Gastric restrictive procedure, with gastric bypass for morbid obesity; with short limb (150 cm or less) Roux-en-Y gastroenterostomy 43847 Gastric restrictive procedure, with gastric bypass for morbid obesity; with small intestine reconstruction