Cultural Transgression and Subversion: the Abject Slasher Subgenre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Copyright © 2021 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization, Strength, and Flaws on Characters’ Mortality Ashley Wellman Texas Christian University & Michele Bisaccia Meitl Texas Christian University & Patrick Kinkade Texas Christian University 128 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Abstract Popular culture has often referenced formulaic ways to predict a character’s fate in slasher films. The cliché rules have noted only virgins live, black characters die first, and drinking and drugs nearly guarantee your death, but to what extent do characters’ basic demographics and portrayal determine whether a character lives or dies? A content analysis of forty-eight of the most influential slasher films from the 1960s – 2010s was conducted to measure factors related to character mortality. From these films, gender, race, sexualization (measured via specific acts and total sexualization), strength, and flaws were coded for 504 non killer characters. Results indicate that the factors predicting death vary by gender. For male characters, those appearing weak in terms of physical strength or courage and those males who appeared morally flawed were more likely to die than males that were strong and morally sound. Predictors of death for female characters included strength and the presence of sexual behavior (including dress, flirtatious attitude, foreplay/sex, nudity, and total sexualization). -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

Read an Excerpt

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

Filmic Bodies As Terministic (Silver) Screens: Embodied Social Anxieties in Videodrome

FILMIC BODIES AS TERMINISTIC (SILVER) SCREENS: EMBODIED SOCIAL ANXIETIES IN VIDEODROME BY DANIEL STEVEN BAGWELL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Communication May 2014 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Ron Von Burg, Ph.D., Advisor Mary Dalton, Ph.D., Chair R. Jarrod Atchison, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A number of people have contributed to my incredible time at Wake Forest, which I wouldn’t trade for the world. My non-Deac family and friends are too numerous to mention, but nonetheless have my love and thanks for their consistent support. I send a hearty shout-out, appreciative snap, and Roll Tide to every member of the Wake Debate team; working and laughing with you all has been the most fun of my academic career, and I’m a better person for it. My GTA cohort has been a blast to work with and made every class entertaining. I wouldn’t be at Wake without Dr. Louden, for which I’m eternally grateful. No student could survive without Patty and Kimberly, both of whom I suspect might have superpowers. I couldn’t have picked a better committee. RonVon has been an incredibly helpful and patient advisor, whose copious notes were more than welcome (and necessary); Mary Dalton has endured a fair share of my film rants and is the most fun professor that I’ve had the pleasure of knowing; Jarrod is brilliant and is one of the only people with a knowledge of super-violent films that rivals my own. -

Word Search 'Crisis on Infinite Earths'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! December 6 - 12, 2019 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H W Q A R C F E B M R A L Your Key 2 x 3" ad O R F E I G L F I M O E W L E N A B K N F Y R L E T A T N O To Buying S G Y E V I J I M A Y N E T X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad U I H T A N G E L E S G O B E P S Y T O L O N Y W A L F Z A T O B R P E S D A H L E S E R E N S G L Y U S H A N E T B O M X R T E R F H V I K T A F N Z A M O E N N I G L F M Y R I E J Y B L A V P H E L I E T S G F M O Y E V S E Y J C B Z T A R U N R O R E D V I A E A H U V O I L A T T R L O H Z R A A R F Y I M L E A B X I P O M “The L Word: Generation Q” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bette (Porter) (Jennifer) Beals Revival Place your classified ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’ Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Shane (McCutcheon) (Katherine) Moennig (Ten Years) Later ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Alice (Pieszecki) (Leisha) Hailey (Los) Angeles 1 x 4" ad (Sarah) Finley (Jacqueline) Toboni Mayoral (Campaign) County Trading Post! brings back past versions of superheroes Deal Merchandise Word Search Micah (Lee) (Leo) Sheng Friendships Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item Brandon Routh stars in The CW’s crossover saga priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” which starts Sunday on “Supergirl.” for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Fears and the Female Circumstance: Women in 1970S Horror Films Lorian Gish

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 2019 Fears and the Female Circumstance: Women in 1970s Horror Films Lorian Gish Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Fears and the Female Circumstance: Women in 1970s Horror Films Lorian Gish BFA Acting for Film, Television, Voice-over, and Commercials Minor: Classical and Medieval Studies Thesis Advisor: Shaun Seneviratne Film Studies Presentation: May 8th, 2019 Graduation: May 23rd, 2019 Gish 1 Abstract More than ever before, stories commenting on real female fears are invaluable to the natural social progression of film as an art form. The core female-centric themes in prominent 1970s horror films are: coming of age, sexual identity, domesticity, pregnancy, and reproductive rights. This thesis first employs empirical research as groundwork for analysis on specific film works by elaborating on expert opinion of the horror genre as well as its foundational elements. Thus, that analysis of the return of repressed fear(s), audience projection of monster and victim, and male gaze, applies to iconic 1970s horror films such as Carrie (1976), Halloween (1978), and Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Films that capture fear comment on universal themes of female perceptions, through specific visual and textual techniques and practices. Gish 2 Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................... -

In Jail Are $10 at the Door

A4 + PLUS >> Burt Reynolds dies at 82, See 2A LOCAL FOOTBALL Starbucks to Tigers take get makeover on Buchholz See Below See Page 1B WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 7 & 8, 2018 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM BOCC BACKS DOWN Friday Old-time music weekend Tax hike nixed/2A Come enjoy a weekend of music, nature and fun along the banks of the Suwannee River at the Stephen Foster CCSO Old Time Music Weekend Photog on September 7- 9 in his- toric White Springs. This three-day event offers par- gets top Weed ticipants in-depth instruc- tion in old-time music tech- niques on the banjo, guitar, nod for vocals, and fiddle for all sale levels. Evening concerts will be poster presented in the Stephen lands Foster Folk Culture Center State Park Auditorium on Friday and Saturday nights at 7 p.m. Instructors will be ‘hoe’ demonstrating their prow- ess on fiddle, banjo, guitar and vocals. Concert tickets in jail are $10 at the door. Workshops instructors will be leading workshops Self-proclaimed prostitute in fiddle, banjo, guitar, and faces sex, drug charges vocals. For more informa- in sting by sheriff’s office. tion call the Events Team at 386- 397-7005 or visit www. By STEVE WILSON floridastateparks.org/park- [email protected] events/Stephen-Foster. An 18-year-old Fort White Anti-bullying fundraiser woman is facing drug and pros- A chicken BBQ will titution charges following a take place, sponsored by mid-day sting earlier this week. Connect Church and The Sarah Williams, who was Power Team, on Friday, born in Tampa Sept. -

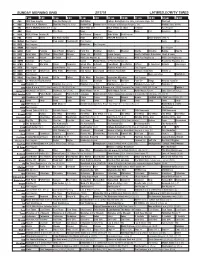

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Remaking Horror According to the Feminists Or How to Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too

Représentations dans le monde Anglophone – Janvier 2017 Remaking Horror According to the Feminists Or How to Have your Cake and Eat It, Too David Roche, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès Key words: horror, remake, feminist film theory, post-feminism, politics. Mots-clés : horreur, remake, théorie féministe, post-féminisme, politiques identitaires. Remakes, as Linda Hutcheon has noted, “are invariably adaptations because of changes in context” (170), and this in spite of the fact that the medium remains the same. What Robert Stam has said of film adaptations is equally true of remakes: “they become a barometer of the ideological trends circulating during the moment of production” because they “engage the discursive energies of their time” (45). Context includes the general historical, cultural, social, national and ideological context, of course, as well as the modes of production and aesthetic trends in the film and television industry. Studying remakes is, then, a productive way to both identify current trends and reconsider those of the past, as well as to assess the significance of a previous work into which the remake offers a new point of entry (Serceau 9), and this regardless of whether or not we deem the remake to be a “successful” film in itself. In this respect, remakes are especially relevant to film and television history and, more generally, to cultural history: they can teach us a lot about the history of production strategies, the evolution of genres, narrative, characterization and style, and of various representations (of an event, a situation, a group or a figure). In a recent article entitled “Zip, zero, Zeitgeist” [sic] posted on his blog (Aug 24, 2014), David Bordwell warns against the tendency of some journalists to see “mass entertainment” as “somehow reflect[ing] its society”: In sum, reflectionist criticism throws out loose and intuitive connections between film and society without offering concrete explanations that can be argued explicitly.