A Case Study of Ancient Temple Food 'Mahaaprasaada'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full of Life (He Tagged Kirron Kher) Colleagues at the Workplace, Says Ganesha

y k y cm UNFAZED PERFORMER FLASH FLOOD HORROR BIDEN WHISPERS IN WISCONSIN Actor Reyhna Pandit says she is unaffected Heavy rain in Himachal Pradesh's US Prez, while talking about repairing roads and bridges, by trolls she receives for playing a Dharamshala led to a flash shifted gears and began speaking and interacting with people in a lowered voice negative role on the screen LEISURE | P2 flood-like situation TWO STATES | P8 INTERNATIONAL | P10 VOLUME 11, ISSUE 103 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | TUESDAY, JULY 13 | 2021 12 PAGES | `5.00 74 die in lightning in UP, Raj and MP AGENCIES Monday. Besides Jaipur, the deaths were reported from New Delhi, July 12: six other districts -- Kota, Lightning strikes in Uttar Jhalawar, Baran, Dholpur, Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Sawai Madhopur and Tonk Pradesh over past 24 hours -- according to the Disaster claimed at least 74 lives, ac- Management and Relief de- cording to data provided by partment. the states governments. It In a major tragedy in was one of the worst light- Jaipur, 12 people, mostly NO GO FOR DEVOTEES: Servitors performing rituals during the annual Rath Yatra festival in Puri, Monday. Devotees were kept away from the festival due to Covid-19 curbs. PTI PHOTO ning disasters in the region youngsters, were killed and in the recent past. 11 injured in an incident of The dead include 11 vis- lightning strike at the iconic itors at 12th century his- watch tower near the Amber toric Amer Fort on the out- Fort, the officials said. Some IRREGULAR by MANJUL skirts of Jaipur who were of them were taking "selfies" Petrol costlier, taking selfies at a watch- on the watch tower, while the tower inside the fort Sunday others were on the hill evening. -

1 Introduction to Conflicts, Religion and Culture in Tourism

1 Introduction to Conflicts, Religion and Culture in Tourism RAZAQ RAJ1* AND KEVIN GRIFFIN2 1Leeds Business School, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK; 2School of Hospitality Management and Tourism, Dublin Institute of Technology Dublin, Ireland Introduction come in to play when one considers themes such as conflict, religion and culture in relation to It has been interesting putting together this book tourism. The book seeks to illustrate the many entitled Conflicts, Religion and Culture in efforts being made to sustain networks of reli- Tourism, which provides a timely assessment of gious principles, to promote the enhancement of the increasing linkages and interconnections ties between religious followers and their sacred between religious tourism and secular spaces on sites. The development of ties between the faith- a global stage. The book explores key learning ful and their commanding figures and principles points from a range of contemporary case studies helps to maintain networks of religious pilgrim- dealing with religious and pilgrimage activity, age for individuals. While much of this activity linked to ancient, sacred and emerging tourist develops in safe, secure, uncontested and support- destinations and new forms of pilgrimage, faith ive environments, in many instances activity oc- systems and quasi-religious activities. curs in liminal, challenged or conflict situations. Religious tourism has increased in the 21st Thus, while Catholics can travel to visit Knock, century, while at same time, looking at world af- Lough Derg or Croagh Patrick (Griffin and Raj, fairs, it would appear that religion and freedom 2015), Muslims can visit Madinah and Makkah of expression are frequently in tremendous con- (Raj and Raja, 2016), Buddhists can visit holy flict. -

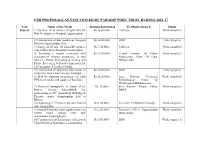

Csr Proposals As Sanctioned by Paradip Port Trust During 2016-17

CSR PROPOSALS AS SANCTIONED BY PARADIP PORT TRUST DURING 2016-17 Year Name of the Work Amount Sanctioned To whom released Status 2016-17 1) Purchase of 18 number of Split ACs for Rs.10,00,000/- Collector Work completed Dist. Headquarters Hospital, Jagatsinghpur. 2) Construction of Bus stand near Naugaon Rs.50,00,000/- BDO Under progress Bazar in Jagatsinghpur Dist. 3) Supply of 50 nos. Of adjustable medical Rs.7,50,000/- Collector Work completed beds to Dist. Hqtrs Hospital, Jagatsinghpur 4) Providing 6 months residential skill Rs.72,00,000/- Central Institute of Plastic Work completed development training programme in two Engineering, Govt. Of India, trades i.e Plastic Processing & Testing and Bhubaneswar. Plastic Processing & Product simulation for 120 unemployed youth of Odisha. 5) Construction of additional class rooms in Rs.20,00,000/- BDO Under progress Sathya Sai Jana Vikash School, Pankapal. 6) Skill development programme for adult Rs.16,20,000/- Asst. Director, Vocational Work completed. PWDs of Odisha with supply of Tool Kits. Rehabilitation Centre for Handicapped, Bhubaneswar. 7) Financial Assisgtancfe in favour of Sri Rs. 75,000/- Shri Rashmi Ranjan Sahoo, Work completed Rashmi Ranjan Sahoo,BBSR for BBSR participating in 50th Asian Body Building & Physique sports championship held at Bhutan. 8) Organising 2nd Children Threatre festival Rs.1,20,000/- Secretary, CANMASS, Paradip. Work completed cum competition 9) Smooth Drinking water supply project at Rs.2,00,000/- Executive Officer, Jagatsinghpur Work completed SDJM Coutrt campus (Dist. Bar Municipality Association, Jagatsinghpur) 10)Construction of Class rooms of Saraswati Rs.5,00,000/- BDO Work completed. -

Experience Marketing — Research, Ideas, Opinions (1)

MiR_9_2019_OKL.qxd 08-10-2019 10:11 Page 1 Cena 59,90 zł (w tym 5% VAT) INDEKS 326224 9/2019 TOM XXVI WRZESIEŃ ISSN 1231-7853 Experience Marketing — research, ideas, opinions (1) Experiential marketing — the state of research in Poland The importance of customer experience for service enterprises www.marketingirynek.pl MiR_9_2019_OKL.qxd 08-10-2019 10:14 Page 3 Komitet redakcyjny: Prof. dr hab. Grzegorz Karasiewicz (redaktor naczelny) Prof. dr hab. Mirosław Szreder (redaktor statystyczny) Mgr Monika Sikorska (sekretarz redakcji) Redaktorzy tematyczni: Spis treści Dr hab. Katarzyna Dziewanowska Dr hab. Agnieszka Kacprzak Uniwersytet Warszawski, Wydział Zarządzania Rada naukowa: Prof. dr hab. Natalia Czuchraj (Narodowy Uniwer- Editorial 2 sytet ,,Politechnika Lwowska”,^ Ukraina) Prof. Ing. Jaroslav Dad’o (Uniwersytet Mateja Bela w Bańskiej Bystrzycy,^ Słowacja) Od redakcji 3 Prof. Ing. Ferdinand Dano (Uniwersytet Ekonomicz- ny w Bratysławie, Słowacja) Prof. dr hab. Tomasz Domański (Uniwersytet Łódzki) Prof. dr hab. Wojciech J. Florkowski (University of Georgia, USA) Experience Marketing — research, ideas, opinions (1) Dr hab. Ryszard Kłeczek, prof. UE (Uniwersytet Eko- nomiczny we Wrocławiu) Dr hab. Robert Kozielski, prof. UŁ (Uniwersytet Łódzki) Prof. Elliot N. Maltz (Willamette University, USA) Prof. dr hab. Krystyna Mazurek-Łopacińska (Uniwer- Experiential marketing — the state of research sytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu) Prof. dr hab. Henryk Mruk (Wyższa Szkoła Zarządza- in Poland 4 nia i Bankowości w Poznaniu) Prof. Durdana Ozretic Dosen (Uniwersytet Zagrzeb- Katarzyna Dziewanowska, Agnieszka Kacprzak ski, Chorwacja) Prof. Gregor Pfajfar (Uniwersytet Lublański, Słowenia) Prof. Seong-Do Cho, Ph.D. (Chonnam National Uni- versity — College of Business Administration, Korea The importance of customer experience Południowa) for service enterprises 15 Dr hab. -

Tourism Under RDC, CD, Cuttack ******* Tourism Under This Central Division Revolves Round the Cluster of Magnificent Temple Beaches, Wildlife Reserves and Monuments

Tourism under RDC, CD, Cuttack ******* Tourism under this Central Division revolves round the cluster of magnificent temple beaches, wildlife reserves and monuments. Tourism specifically in Odisha is pilgrimage oriented. The famous car festival of Puri Jagannath Temple has got the world wide acclaim. It holds attraction of all domestic, national and international tourists, Sea Beaches like Puri, Konark, Astarang of Puri District, Digha, Talasari, Chandipur of Balasore, Siali of Jagatsinghpur District keeps the beholder at its clutch. Wild life reserves like Similipal of Mayurbhanj, Bhitarkanika of Kendrapara along with scenic beauty of nature makes one mesmerized and gives a feeling of oneness with nature, the part of cosmic power. BALASORE KHIRACHORA GOPINATH TEMPLE: Khirachora Gopinatha Temple is situated at Remuna. It is famous as Vaishnab shrine. Remuna is a Chunk of Brindaban in Orissa. It is a little town located 9 k.m east of Balasore. The name Remuna is resulting from the word Ramaniya which means very good looking. "Khirachora" in Odia means Stealer of Milk and Gopinatha means the Divine Consort of Gopis. The reference is to child Krishna's love for milk and milk products. (Khirachora Gopinath Temple) PANCHALINGESWAR TEMPLE: Panchalingeswar is located on a top of a hillock near the Nilagiri hill which is popular for its natural surroundings. The main attraction of this place is a temple having five lingas with a perennial stream, which is regularly washes the Shivalingas as it flows over them. So, to reach to the temple one has to lie flat on the rock parallel to the stream to touch and worship the lingas inside the water stream. -

Census of India 1991

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES-19 ORISSA PART IX-A TOWN DIRECTORY Directorate of Census Operations, Orissa REGISTRAR GENERAL OF INDIA (in charge of the census of India and vital statistics) Office Address: 21A Mansingh Road New Delhi no 011, India Telephone: (91-11)338 3761 Fax: (91-11)338 -3145 Email : [email protected] Internet: htto:llwww.censusindia.net Registrar General of India's publications can be purchased from the following : • The Sales Depot (Phone: 338 6583) Office of the Registrar General of India 2/A Mansingh Road New Del~ 110 011, India • Directorates of Census Operations in the capitals of all states and union territories in India • The Controller of Publication Old Secretariat, Civil tines Delhi - 110 054 • Kitab Mahal State Emporia Complex, Unit No. 21 Baba Kharak Singh Marg, New Delhi 11 O' 001. • Sales outlets of the Controller of Publication allover India Census data available on floppy disks can be purchased from the following: • Office of the Registrar General, India Data Processing Division 2nd Floor, 'E' Wing Pushpa Bhawan Madangir Road New Delhi - 110 062, India Telephone: (91-11) 608 1558 Fax : (91-11) 608 0295 Email : [email protected] © Registrar General of'India The contents of this publication may be quoted citing the source clearly .(ii) CONTENTS Page No FOREWARD v PREFACE vii SECTi,lON-A Analytical note (i) General introduction 3 (ii) Census concepts and Urban Area 3 (iii) Scope of State Level 'Town Directory 10 (iv) Analysis of data s::overed in the Town Directory Statements and P.C.A. -

Shree Baladevjew and Ratha Yatra of Kendrapara

Odisha Review ISSN 0970-8669 ulasi Kshetra, the abode of TTulasi is the ancient name of Kendrapara. It is one of the holiest places of Bharat Varsha. Shree Baladevjew is the presiding deity of Baladevjew temple of this kshetra. The excellence of Tulasi Kshetra is described in some puranas and scriptures. The significance of Sri Baladevjew and Tulasi Kshetra is also rightly mentioned in “Brahma Tantra”- “Varshanam Vharatah shrestha Desam Utkal Tatha Shree Baladevjew and Ratha Yatra of Kendrapara Dr. Sarbeswar Sena Utkale shrestha Tirthana situated in 20°49’E. Latitude and 86°25’E to Krushnarka parbuti 87°.1’E.Longitude and the district headquarter Yatrayam Halayudha Gachhet being the same. The district is surrounded by Tulasikshetra Tisthati Bhadrak, Jajpur, Cuttack and Jagatsinghpur Utkale Panchakshetrancha districts and Bay of Bengal in the east. The river Badanti Munipungabah.” Luna (a branch of the Mahanadi) and other rivers Kendrapara has its special identity in the that flow in Kendrapara district are Karandia, world tourism map for Shree Baladevjew and Gobari, Chitrotpala and Hansua. Aul, some world famous eco-tourist spots. Derabish, Garadpur, Mohakalpara, Marshaghai, Introducing Kendrapara: Kendrapara, Rajanagar, Rajkanika, Pattamundai are the nine blocks of the district. Kendrapara originally belongs to undivided Cuttack district becomes a sub-division Kendrapara is 59 km far from Cuttack. (1859) and at last a district (1993 A.D.)It is One can reach the district headquarters by bus JUNE - 2017 129 ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review from Cuttack via Jagatpur on Cuttack-Salipur twelfth day of the bright fortnight of the month state highway or on the National highway No.-5 Magha. -

Minutes of the Cross-Party Group on Building Bridges with Israel Meeting of the 21St June 2017

Minutes of the Cross-Party Group on Building Bridges with Israel Meeting of the 21st June 2017 Sederunt Jackson Carlaw MSP Peter Speirs Scotland Director, Jewish Leadership Council Stanley Lovatt Honorary Consul of Israel in Scotland Stanley Grossman Scottish Friends of Israel Nathan Wilson Office of Jackson Carlaw MSP Michael Kusznir Office of Jackson Carlaw MSP Leon Thompson Visit Scotland Atilla Incecik University of Strathclyde Rabbi David Rose Edinburgh Hebrew Congregation Nigel Goodrich Confederation of Friends of Israel, Scotland Daniel McCroskrie Office of Donald Cameron MSP John Mason MSP Jamie Greene MSP Richard Lyle MSP Nick Naddell Burness Paull Linor Kirkpatrick Israelis in Scotland Danielle Bett ScoJeC/Israelis in Scotland Itamar Nitzan Personal capacity Evy Yedd Glasgow Jewish Representative Council Christina Jones Glasgow Friends of Israel Liz Cabb PPS Edinburgh Douglas Flett International Christian Chamber of Commerce Micheline Brannan ScoJeC Bill Bowman MSP Rachael Hamilton MSP Myer Green Scottish Friends of Israel Sammy Stein Glasgow Friends of Israel Alistair Barton Director, Pray for Scotland Kush Boparai Israel Embassy Nathan Tsror Head of Economic and Trade Ministry, Israeli Embassy Ruth Kennedy Centre for Scotland and Israel Relations Jackson Carlaw (JC) welcomed all attendees, particularly the MSPs JC put forward the minutes of the previous meeting – these were proposed by Bill Bowman (BB) MSP and seconded by Evylin Yedd. Ruth Kennedy (RK) brought to the Group’s attention that the Women’s International Zionist Organisation (WIZO) will be in Aberdeen in the coming months and are hoping to exhibit their work publicly in the Scottish Parliament Nigel Goodrich (NG) circulated flyers for the upcoming Shalom Festival, and thanked Edinburgh City Council for providing a venue for the event on August 8, 9, and 10. -

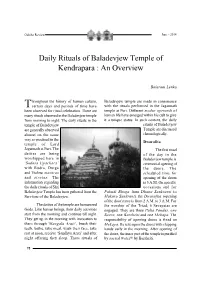

Daily Rituals of Baladevjew Temple of Kendrapara : an Overview

Odisha Review June - 2014 Daily Rituals of Baladevjew Temple of Kendrapara : An Overview Balaram Lenka hroughout the history of human culture, Baladevjew temple are made in consonance Tcertain days and periods of time have with the rituals performed in the Jagannath been observed for ritual celebration. There are temple at Puri. Different modus operandi of many rituals observed in the Baladevjew temple human life have emerged within his cult to give from morning to night. The daily rituals in the it a unique status. In such context, the daily temple of Baladevjew rituals of Baladevjew are generally observed Temple are discussed almost on the same chronologically. way as practised in the Dwarafita temple of Lord Jagannath at Puri. The The first ritual deities are being of the day in the worshipped here in Baladevjew temple is ‘Sodasa Upachara’ ceremonial opening of with Rudra, Durga the doors. The and Vishnu mantras scheduled time for and strotas. The opening of the doors information regarding is 5 A.M. On specific the daily rituals of Shri occasions and for Baladevjew Temple has been gathered from the Pakudi Bhoga from Dhanu Sankranti to Servitors of the Baladevjew. Makara Sankranti, the Dwarafita (opening of the door) time is from 2 A.M. to 3 A.M. For The deities of the temple are humanized the worship of the Triad, 6 Sevayatas are Gods. Like human beings, their daily activities engaged. They are three Palia Pandas, one start from the morning and continue till night. Suara, one Barsheiti and one Mekapa. The They get up in the morning with invocation to responsibility of opening doors is fixed on them through ‘Mangala Arati’, brush their Mekapa. -

A Life-Changing Experience”

“A LIFE-CHANGING EXPERIENCE” 30TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE KAS/AJC PROGRAM Deidre Berger | Jens Paulus (Hrsg.) ISBN 978-3-941904-58-3 www.kas.de CONTenT 7 | FOreWORD Michael Thielen 9 | inTRODUCTION David A. Harris 13 | MeSSage TO MarK The 30 TH anniVerSarY OF The exchange prOgraM OF The KOnraD-ADenaUer- STif TUng anD The AMerican JeWISH COMMITTee Angela Merkel 15 | OveRVIEW: 30 YeaRS COOpeRATION kas/ajc EXCHANGE PROGRAM 17 | 30 YearS COOperaTION: KAS anD AJC SOME THOUghTS ON HOW The COOperaTION WITH JeWISH OrganiZATIONS STarTED Josef Thesing 33 | BUilDing BriDgeS acrOSS Deep DIVIDES Published by the American Jewish Committee and gerMan anD AMerican JEWS Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Beate Neuss 2nd, revised version. © 2010, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin 59 | “The ADenaUer”: A 30 Year PerSOnal American Jewish Committee, Berlin RETROSpecTIVE Eugene DuBow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, without written permission of the publisher. 63 | EXpeRIENces OF AMERIcaN paRTICIpaNTS Translations: 65 | preface Joelle Burbank, Isabelle Hellmann†, Volker Raatz, Marc Levitt, Grit Seidel, Wolfram Wießner. Deidre Berger Layout: SWITSCH KommunikationsDesign, Cologne. Printed by: Druckerei Franz Paffenholz GmbH, Bornheim. 67 | DAVID M. GORDIS (1980) Printed in Germany. 68 | STEVen L. SWig (1982) This publication was printed with financial support of the Federal Republic of Germany. 69 | NancY PETScheK (1982) 70 | MONT S. LEVY (1983) ISBN 978-3-941904-58-3 71 | GEOrge A. MaKraUer (1983) 74 | JON BriDge (1983) 125 | eXpeRIENces OF GERMAN paRTICIpaNTS 74 | KenneTH D. MaKOVSKY (1985 & 1988) 78 | Rhea SchWarTZ (1985) 127 | inTRODUCTION 79 | ANDrea L. -

Lord Jagannath and Odia Nationalism

Lord Jagannath and Odia Nationalism Dr. A.C. Padhiary, IAS (Retired), Bhubaneswar, Odisha The culture of Lord Jagannath has been inextricably linked with history of Odisha, its people, religion and geography. There has been repeated raids and incursions by outsiders like Afgans, Marathas, Muslims & Britishers but Lord Jagannath & its culture has withstood all inroads & Vicissitudes of history. In other words, the contribution of Jagannath culture in various ways have developed Odia Nationalism which, has withstood the revages of time and integrated the Odisha society into a pluralistic & homogenous body politic. The concept of Odia nationalism owes its origin to basically two important factors i.e. Odia language‟s development and Lord Jagannath‟s supremacy over the King & kingdom of Odisha. Even the language centered nationalism was closely linked with the Jagannath- centered Nationalism. The factors that hindered the smooth and systematic development of language based nationalism was that some of the monarchs of medieval period were also Telugu Speakers and the higher caste persons like Brahmins who used Sanskrit as their language for which they felt proud of. “Even the caste ridden society did not overwhelmly appreciate the translation of Bhagabat by Jagannath Das ascribing as Teli-Bhagbat. So also Mahabharat of Sarala Das, Ramayan of Balaram Das & Hari Vamsa by Achutananda Das has not well appreciated by higher caste people. This was another hindrance against language centered nationalism. In fact the Death of King Mukunda Deb, the advent of Srichaitanya, the recovery of relics of Sri Jagannath and installation of Jagannath at Puri, and taking over administration by Afgans & Moguls later are some of the factors that heralded the formative period of development of Odia nationalism. -

List of Colleges Failed to Updating

LIST OF COLLEGES FAILED TO UPDATING "PIMS" (Submitted by NIC as on 03/02/2017) College Code Collegename District Block 3023302 Anchalik Degree College, Paharsirigida Bargarh Atabira 23104301 Pendrani (Degree) Mahavidyalaya, Umerkote Nawarangpur Umerkote 3055301 Imperial Degree College, Vidya Vihar, Chadeigaon Baragarh Bhatali 3133303 Jamla Degree College, Jamla Baragarh Rajborasambar 3155302 Jayadev Institute of Science & Technology, Padampur Baragarh Padampur (NAC) 3033306 Katapali (Degree) College, Katapali Baragarh Bargarh 3022304 Larambha (Degree) College, Larambha Baragarh Attabira 3062305 Pallishree (Degree) College, Chichinda Baragarh Bheden 3053403 Shakuntala Bidyadhar Women's Degree College, Kamgaon Baragarh Bhatali 3035303 Vikash Degree College, Bargarh Baragarh Bargarh 5065303 Balaji Degree College, NH-26, Sambalpur Road, Bolangir Bolangir Puintala 5075306 Nice College of +3 Commerce, Bolangir Bolangir Balangir (MPL) 5025303 Yuvodaya College of Advanced Technology, Sakma Bolangir Balangir 23125302 G.K. Science Degree College, Umerkote Nawarangpur Umerkote (NAC) 1045101 Vidya Bharati Residential (Junior) College, Angul Angul Angul (NAC) 1045102 Saraswati Shishu Vidyamandir +2 College, Gandhi Marg Angul Angul (NAC) 1015101 Siddhi Vinayak Science College, Similipada Angul Angul 1015103 Sriram Dev(Junior) Mahavidyalaya, Angul Angul Angul 1023304 Anchalika (Degree) College, Talmul Angul Banarpal 1015105 Mahima Jyoti (Junior) Sc. College, Angul Angul Angul 1015104 Sri Aurobindo College of +2 Sc. & Commerce, Khalari Angul