The 1918 Influenza in Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Canadian Charities Had the Largest Assets in 2014?

www.canadiancharitylaw.ca Which Canadian charities had the largest assets in 2014? By Mark Blumberg (March 23, 2016) We recently reviewed the T3010 information for 2014. It covers about 84,370 of the 86,000 registered charities that have so far filed their return and that have been entered into the CRA’s database. Canadian registered charities are currently required to disclose on the T3010 their assets. The total assets of all the 84,370 registered charities were about $373,050,327,255.00. Below we have a table of Canadian charities and how much they spent as reported for the 2014 fiscal year. Thank you to Celeste Bonas, an intern at Blumbergs, for helping with this project. The Sean Blumberg Transparency Project is in memory of my youngest brother Sean Blumberg. Sean was a sweet, kind person, a great brother who helped me on a number of occasions with many tasks including the time consuming and arduous task of reviewing T3010 databases and making them into something useful. As part of the Sean Blumberg Transparency Project, Blumbergs has been releasing information on the Canadian charity sector to provide a better understanding of the size, scope, complexity and challenges of the sector. Please review my caveats at the end about the reliability and usage of T3010 information. 1 www.canadiancharitylaw.ca List of Canadian charities with the largest assets in 2014 Line 4200 Name of Canadian Registered Charity largest assets 1. ALBERTA HEALTH SERVICES $9,984,222,000.00 2. THE MASTERCARD FOUNDATION $9,579,790,532.00 3. THE GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO $7,681,040,000.00 4. -

1918/19: 100 Years On

ESSAYS Ewald Frie 1918/19: 100 YEARS ON Open Futures 1918/19 – War and victory, collapse and defeat, revolution and reform, peace and re- organisation, civil war and violence, famine and Spanish flu and much else. The elements can be separated analytically, and many of them have been analysed individually in a historical context. They have been interpreted and incorporated into the narratives of revolution research, the history of warfare and violence, peace research, the history of diseases and epidemics. But the historical dynamics of 1918/19 resulted from the interplay of the various elements in very different constellations. 1918/19 is therefore a challeng- ing anniversary for a historical scholarship that is exploring new conceptual territory: – spatially: leaving the construct of the nation state and instead ›playing with scales‹1 from the local to the global; – temporally: departing from era- and progress-based master narratives and instead ›zooming in and out‹ and playing with temporal perspectives;2 – conceptually: departing from conceptual constructs due to the blurring of categories like ›crisis‹3 or ›revolution‹4 and instead focusing on a broad range of phenomena of social transformation on the premise of ›multidimensional understandings of emergence and destabilization‹.5 1 E.g. James Retallack (ed.), Imperial Germany 1871–1918, Oxford 2008. 2 E.g. Emily S. Rosenberg (ed.), A World Connecting. 1870–1945, Cambridge 2012 (A History of the World, ed. by Akira Iriye and Jürgen Osterhammel). 3 Cf. Thomas Mergel (ed.), Krisen verstehen. Historische und kulturwissenschaftliche Annäherungen, Frankfurt a.M. 2012, pp. 9-22, and the Leibniz Research Alliance ›Crises in a Globalised World‹: <http://www.leibniz-krisen.de/en/start/>. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

The Spanish Flu

through electron microscopes, would that actually than normal for the elderly. The common have empowered them to halt the pandemic? explanation is that this strain of influenza was so There was no cure for the disease then, or now. new that it startled its victims' immune systems Vaccines? Another generation would pass before into overreaction, and the more vigorous the even partially effective vaccines against victim, the greater and deadlier the overreaction. influenza were developed. Even if all the The defensive swelling of membranes and knowledge and technology to produce flu increased secretion of fluids of the respiratory vaccine had been at hand in 1918, would it have system went to extremes in young adults, filling been possible to produce it in sufficient quantity their lungs with liquid until they drowned. and to distribute it across oceans and continents Overstimulation of the immune system is a in time to stop the swiftly spreading breath- plausible theory, but we could subject it to borne pandemic? Even today, when similar rigorous testing only if something like the 19 18 questions are asked each time a new virus returned. strain of the virus appears, the answer falls short of This distinctive influenza epidemic swept over being a confident "yes.” the world in three major waves during 1918 and 1919. We cannot be sure where and when the The influenza of the 1900s is still something of an initial wave in the spring of 1918 started, but the enigma, but the influenza that was sweeping around earliest scientific and statistical evidence points the world at the time of the Armistice ending to the United States in March 1918. -

Which Canadian Charities Had the Largest Assets in 2015?

www.canadiancharitylaw.ca Which Canadian charities had the largest assets in 2015? By Mark Blumberg (June 10, 2017) We recently reviewed the T3010 information for 2015. It covers about 84,442 of the 86,000 registered charities that have so far filed their return and that have been entered into the CRA’s database. Canadian registered charities are currently required to disclose on the T3010 their assets. The total assets of all the 84,442 registered charities were about $397,833,310,726.00. Below we have a table of Canadian charities that had assets of over $10 million as identified for the 2015 fiscal year. Thank you to Celeste Bonas, an intern at Blumbergs, for helping with this project. The Sean Blumberg Transparency Project is in memory of my youngest brother Sean Blumberg. Sean was a sweet, kind person, a great brother who helped me on a number of occasions with many tasks including the time consuming and arduous task of reviewing T3010 databases and making them into something useful. As part of the Sean Blumberg Transparency Project, Blumbergs has been releasing information on the Canadian charity sector to provide a better understanding of the size, scope, complexity and challenges of the sector. Please review my caveats at the end about the reliability and usage of T3010 information. 1 www.canadiancharitylaw.ca List of Canadian charities with the largest assets in 2015 Line 4200 Name of Canadian Registered Charity Largest assets 1. THE MASTERCARD FOUNDATION $12,704,351,331.00 2. ALBERTA HEALTH SERVICES $10,140,366,000.00 3. -

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Comprehensive Study Report Prepared for: Environment Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Transport Canada Hamilton Port Authority Prepared by: The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group AECOM October 30, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group Members: Roger Santiago, Environment Canada Erin Hartman, Environment Canada Rupert Joyner, Environment Canada Sue-Jin An, Environment Canada Matt Graham, Environment Canada Cheriene Vieira, Ontario Ministry of Environment Ron Hewitt, Public Works and Government Services Canada Bill Fitzgerald, Hamilton Port Authority The Technical Task Group gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following parties in the preparation and completion of this document: Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Hamilton Port Authority, Health Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ontario Ministry of Environment, Canadian Environmental Assessment Act Agency, D.C. Damman and Associates, City of Hamilton, U.S. Steel Canada, National Water Research Institute, AECOM, ARCADIS, Acres & Associated Environmental Limited, Headwater Environmental Services Corporation, Project Advisory Group, Project Implementation Team, Bay Area Restoration Council, Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan Office, Hamilton Conservation Authority, Royal Botanical Gardens and Halton Region Conservation Authority. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. -

The Role of Pawnshops in Risk Coping in Early Twentieth-Century Japan∗ Tatsuki Inoue†

The role of pawnshops in risk coping in early twentieth-century Japan∗ Tatsuki Inoue† Abstract This study examines the role of pawnshops as a risk-coping device in prewar Japan. Using data on pawnshop loans for more than 250 municipalities and exploiting the 1918–1920 influenza pandemic as a natural experiment, we find that the adverse health shock increased the total amount of loans from pawnshops. This is because those who regularly relied on pawnshops borrowed more money from them than usual to cope with the adverse health shock, and not because the number of people who used pawnshops increased. Keywords: Pawnshop; Risk-coping strategy; Borrowing; Influenza pandemic; Prewar Japan ∗ I would like to express my gratitude to Tetsuji Okazaki, Kota Ogasawara, and participants at the Economic History Society Annual Conference 2019 at Queen’s University Belfast and 2019 Japanese Economic Association Spring Meeting at Musashi University for their helpful comments. This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (Grant Number: 17J03825). Any errors are my own. † Graduate School of Economics, The University of Tokyo, Akamon General Research Building, 3F 353, 7-3-1, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan. E-mail: inoue- [email protected]. 1 Introduction Most industrialized countries were characterized by huge income inequality before World War II (Piketty 2014). Since formal systems of social insurance were underdeveloped, the poor were more vulnerable to unforeseen accidents such as illness than today’s poor people in developed countries. Furthermore, an increase in migration removed people from the traditional informal social insurance systems provided by their local communities (Gorsky 1998). -

The Spanish Flu and the First World War: a Historical Analysis of the Pandemic’S Impact on the Conduct of War and Its Lessons for the British Army of 2020

CHACR IN DEPTH BRIEFING CIRCULATION: PUBLIC 6 MAY 2020 The Spanish Flu and the First World War: A Historical Analysis of the Pandemic’s Impact on the Conduct of War and its Lessons for the British Army of 2020 Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston . From Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine The influenza pandemic, also known as the Spanish Flu, which hit the World the 1918 and last- ed until 1920, was the deadliest outbreak of disease in the 20th century. The aim of this study is to analyse the impact that the pandemic had on the belligerent nations of the First World War and, in particular, their armies. How were the armies affected, what impact did the pan- demic have on the ability to fight, and what measures did the armies take to contain the vi- rus? Last, but not least, the study will offer some possible consequences and lessons for the British Army of today. Considering that CHACR supports the British Army, it is fitting that the emphasis lies on the UK experience of the Spanish Flu; however, other armies and nations are also taken into consideration to present a more all-encompassing picture of the situation and challenges that the Spanish Flu presented at the end of the First World War. IN DEPTH BRIEFING Page 2 In order to answer the questions above, the study is divided into three parts. Part one presents an overview of the Spanish Flu pandemic and thus provides the context for the following parts. -

Capital Projects' Status and Closing Report As of September 30Th, 2010 (FCS10073(A)) (City Wide)

CITY OF HAMILTON CORPORATE SERVICES DEPARTMENT Financial Planning & Policy Division TO: Mayor and Members WARD(S) AFFECTED: CITY WIDE General Issues Committee COMMITTEE DATE: February 14th, 2011 SUBJECT/REPORT NO: Capital Projects’ Status and Closing Report as of September 30th, 2010 (FCS10073(a)) (City Wide) SUBMITTED BY: PREPARED BY: Roberto Rossini, General Manager, John Dibattista 905-546-2424 x 4371 Finance & Corporate Services SIGNATURE: RECOMMENDATION: (a) That the September 30th, 2010, Capital Projects’ Status and Projects’ Closing Report and the attached Appendices A, B, C, D, and E to report FCS10073(a) for the tax levy and the rate supported capital projects be received for information; (b) That the General Manager of Finance & Corporate Services be directed to close the completed capital projects listed in Appendix B to report FCS10073(a) in accordance with the Capital Closing Policy and that the net transfers be applied as listed below and as detailed by project in Appendix B to report FCS10073(a): Summary of Transfers: Transfers to/(from) Reserves From the Unallocated Capital Levy -108020 (221,217) Vision: To be the best place in Canada to raise a child, promote innovation, engage citizens and provide diverse economic opportunities. Values: Honesty, Accountability, Innovation, Leadership, Respect, Excellence, Teamwork SUBJECT: Capital Projects’ Status and Closing Report as of September 30th, 2010 FCS10073(a) (City Wide) - Page 2 of 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents the capital projects’ status for both the tax and the rate supported capital budgets, as submitted by operating departments, and is based on forecasted and committed expenditures to September 30th, 2010. -

“Pandemic 1918” Study Guide Questions

“Pandemic 1918” Study Guide Questions “Pandemic 1918!” is an article about the experiences of King County residents during the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. The virus, nicknamed the Spanish Flu, arrived just as the First World War was ending. It is thought to have infected over 500 million people worldwide. This activity is designed for readers in 7th grade and above. Questions can be used for discussion or as writing prompts. You can find the original article from December 2014 on Renton History Museum’s Newsletters Page. 1. Today’s scientists and historians are not sure where the Spanish Flu originated, but it is unlikely that it actually began in Spain. Why was the epidemic called the Spanish Flu? 2. How did health officials in the state of Washington prepare for the arrival of the Spanish Flu? 3. Jessie Tulloch observed firsthand how Seattle adapted to the flu. How did everyday life in Seattle change? 4. On November 11, 1918, the Allied Powers and Germany signed a treaty that officially brought World War I to a close. This day was called Armistice Day, and in modern times it is celebrated as Veteran’s Day in the United States. Why was the first Armistice Day a concern for public health officials? 1 5. According to health officials at the time, the best place for treating the Spanish Flu was at home. Patients were treated in their homes with the aid of family members and traveling nurses and doctors. However, some of the infected individuals had to go to Renton Hospital for treatment. -

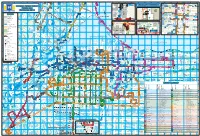

HSR Customer C D O W Hunter St

r r C D e k a r n o r s D o t b is t t r r a l Mo L s C n e D m e te s e e n g v n S r R o h i P M C o a C s m h o o r K W O i e C lo s ms a M a m n F d g s lk d u ff o A s i a H te on r e n C i r u a Dr t y N te a lic l r e a g y o v L rm ic C de 's u n r t R e P a a e D F A ld l s ti a Cumberlandd t o l n L v r t u a n iti n W i l r C in r gh a y n a u e o D D e o a D C Dr e w m S d r r a s m t A M n e r o C v a C C M e v A S F lv R h e l R c t t lm l v Guelph Line e or v e W G A r c r re a P a v v Laurentian en L n R en A R i c a l d s a yatt Rd b a r t D v A c e ni A t a s C r d e a T n t ie ie A t u C C o r k t h rt n D i r t r d g C a e la Dr C il r a r e a p e R e C M y A kvi D C T y a e n v O a d R w r C l a L o k B t w w F O A e e k T o L v l e o a La r a d a u r v n k f le R a is w D e or a d d to ic r sid t t Pear id P Fi c k Spruce e C C M s k M ge h P v S A t C ree gsbrid o D l Brant St M Kin s er H r ap New St Pi O im v T s o A n h G A m le e ak o t r r Ct Fisherv n r l e h a l C w r e D C n w il l s e C o l L i o o D o w o D r ve o r N o h d t n l p t M d Harvester Rd D r e a R ic r w C to r D y e y L d h w l o n t olson Ct o r o e M a p A l c f s e B s v il m z B a s R u u d r d ln B P a d U G a u r r o a er le W W e a v C n r t p c rtv T H l R D C ko e r S iew B mesbu d P r nd r y R B H ay Dr A r d r F a ingw D Concession 8 E C m y i a D o r l e u e t m C n R h s i t r e J tl C e S w e d o a t r C l l W n d c t l A a h C e a s s r l n t i d n e a l rpi D R J r e n e li s to r A r vl e e le n v n C t n v i t d g o C ffe -

Hospital Lhins Contact List

Hospital LHINs Contact List Patient Hospital LHIN Hospital LHIN LHIN Hospital Inquiry or Main Direct # or Address Map Fax # Number Extension Hotel-Dieu Grace Healthcare 519-257-5111 1453 Prince Rd Map it! (HDGH)(Windsor) Windsor, ON N9C 3Z4 Leamington District Memorial 519-326-2373 194 Talbot St W Map it! Hospital Leamington, ON N8H 1N9 Windsor Regional Hospital- 519-254-5577 1995 Lens Ave Map it! Metropolitan Campus Windsor, ON N8W 1L9 Windsor Regional Hospital- 519-253-5253 2220 Kildare Rd Map it! Erie St Clair LHIN Windsor Regional Cancer Windsor, ON N8W 2X3 1-888-447-4468 Centre Windsor Regional Hospital- 519-973-4411 1030 Ouellette Ave Map it Ouellette Campus Windsor, ON N9A 1E1 Chatham-Kent Health 519-352-6400 80 Grand Ave W Map it! Alliance-Chatham Campus Chatham, ON N7M 5L9 Chatham-Kent Health 519-352-6400 325 Margaret Ave Map it! Alliance Sydenham Campus Wallaceburg ON, N8A 2A7 Bluewater Health 419-464-4400 89 Norman St Map it! Sarnia, ON N7T 6S3 Charlotte Eleanor Englehart 519-882-4325 450 Blanche St Map it! Hospital of Bluewater Health Petrolia, ON N0N 1R0 1 Jan 2012 (Update Oct 12, 2016) Hospital LHIN(s) Contact List - Ontario Page 1 of 15 Patient Hospital LHIN Hospital LHIN LHIN Hospital Inquiry or Main Direct # or Address Map Fax # Number Extension Middlesex Hospital Alliance- 519-693-4441 519-474-5662 519-472-4045 1824 Concession Dr Map it! Four Counties Health Services Newbury, ON N0L 1Z0 Middlesex Hospital Alliance- 519-245-5295 519-474-5662 519-472-4045 395 Carrie St Map it! Strathroy Middlesex General Strathroy, ON N7G 3J4 Hospital London Health Sciences Centre 519-685-8500 519-474-5662 519-472-4045 800 Commissioners Rd E Map it! - Victoria Hospital London, ON N6A 5W9 London Health Sciences 519-685-8500 519-474-5662 519-472-4045 339 Windermere Rd Map it! Centre-University Hospital London, ON N6A 5A5 St Joseph's Health Care 519-646-6100 519-474-5662 519-472-4045 268 Grosvenor St Map it! London- St.