Memoirs of Jeremiah Curtin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kyiv in Your Pocket, № 56 (March-May), 2014

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Kyiv March - May 2014 Orthodox Easter Ukrainian traditions Parks & Gardens The best places to experience the amazing springtime inyourpocket.com N°56 Contents ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Arrival & Getting around 6 Getting to the city, car rentals and transport The Basics 8 All you’d better know while in Kyiv History 11 A short overview of a rich Ukrainian history Orthodox Easter 12 Ukrainian taditions Culture & Events 14 Classical music, concerts and exhibitions schedules Where to stay 18 Kviv accommodation options Quick Picks 27 Kyiv on one page Peyzazhna Alley Wonderland Restaurants 28 The selection of the best restaurants in the city Cafes 38 Our choice from dozens of cafes Drink & Party 39 City’s best bars, pubs & clubs What to see 42 Essential sights, museums, and famous churches Parks & Gardens 50 The best place to expirience the amazing springtime Shopping 52 Where to spend some money Directory 54 Medical tourism, lifestyle and business connections Maps & Index Street register 56 City centre map 57 City map 58 A time machine at Pyrohovo open-air museum Country map 59 facebook.com/KyivInYourPocket March - May 2014 3 Foreword Spring in Kyiv usually comes late, so the beginning of March does not mean warm weather, shining sun and blossoming flowers. Kyiv residents could not be happier that spring is coming, as this past winter lasted too long. Snow fell right on schedule in December and only the last days of Febru- Publisher ary gave us some hope when we saw the snow thawing. Neolitas-KIS Ltd. -

1882. Congressional Record-Senate. 2509

1882. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 2509 zens of Maryland, .for the establishment of a light-house at Drum· Mr. HAMPTON presented a memorial of the city council of Charles Point Harbor, Calvert County, Maryland-to the Committee on Com ton, South Carolina., in favor of an appropriation for the completion merce. of the jetties in the harbor at that place; which was referred to the By Mr. .CRAPO: The petition of Franklin Crocker, forTelief-to Committee on Commerce. the Committee on Claims. He also presented a petition of inmates of the Soldiers' Home, of By Mr. DE MOTTE: The petition ofJolmE. Hopkinsand91 others, Washington, District of Columbia, ex-soldiers of the Mexican and citizens of Indiana, for legislation to regulate railway transporta Indian wars, praying for an amendment of section 48~0 of the Revised tion-to the Committee on Commerce. Statutes, so a-s to grant them an increase of pension; which was By :Mr. DEUSTER: Memorial of the Legislature of Wisconsin, . referred to the Committee on Military Affairs. asking the Government for a. cession of certain lands to be used for Mr. ROLLINS presented the petition of ex-Governor James .A. park }Jurposes-to the Committee on the Public Lands. Weston, Thomas J. Morgan, G. B. Chandler, Nathan Parker, and · Also, the petition of E . .Asherman & Co. and others, against the other citizens of Manchester, New Hampshire, praying for the pas pas a~e of the "free-leaf-tobacco" bill-to the Committee on Ways sage of the Lowell bill, establishing a uniform bankrupt law through and 1\ieans. -

Briefing Policies for Children In

1 BROOKINGS INSTITUTION BROOKINGS-PRINCETON "FUTURE OF CHILDREN" BRIEFING POLICIES FOR CHILDREN IN IMMIGRANT FAMILIES INTRODUCTION, PRESENTATION, PANEL ONE AND Q&A SESSION Thursday, December 16, 2004 9:00 a.m.--11:00 a.m. Falk Auditorium The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 [TRANSCRIPT PREPARED FROM TAPE RECORDINGS.] 2 PANEL ONE: Moderator: RON HASKINS, Senior Fellow Economic Studies, Brookings Overview: DONALD HERNANDEZ, Professor of Sociology, University at Albany, SUNY MELVIN NEUFELD, Kansas State House of Representatives, Chairman, Kansas House Appropriations Committee RUSSELL PEARCE, Arizona State House of Representatives, Chairman, Arizona House Appropriations Committee FELIX ORTIZ, New York State Assembly 3 THIS IS AN UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT. P R O C E E D I N G S MR. HASKINS: Good morning. My name is Ron Haskins. I'm a senior fellow here at Brookings and also a senior consultant at the Annie Casey Foundation. I'd like to welcome you to today's session on children of immigrant families. The logic of the problem that we're dealing with here is straightforward enough, and I think it's pretty interesting for both people left and right of center. It turns out that we have a lot of children who live in immigrant families in the United States, and a large majority of them are already citizens, even if their parents are not. And again, a large majority of them will stay here for the rest of their life. So they are going to contribute greatly to the American economy for four or five decades, once they get to be 18 or 21, whatever the age might be. -

The Ideological Origins of the Population Association of America

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield Sociology & Anthropology Faculty Publications Sociology & Anthropology Department 3-1991 The ideological origins of the Population Association of America Dennis Hodgson Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/sociologyandanthropology- facultypubs Archived with permission from the copyright holder. Copyright 1991 Wiley and Population Council. Link to the journal homepage: (http://wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/padr) Peer Reviewed Repository Citation Hodgson, Dennis, "The ideological origins of the Population Association of America" (1991). Sociology & Anthropology Faculty Publications. 32. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/sociologyandanthropology-facultypubs/32 Published Citation Hodgson, Dennis. "The ideological origins of the Population Association of America." Population and Development Review 17, no. 1 (March 1991): 1-34. This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ideological Origins of the Population Association of America DENNIS HODGSON THE FIELD OF POPULATION in the United States early in this century was quite diffuse. There were no academic programs producing certified demographers, no body of theory and methods that all agreed constituted the field, no consensus on which population problems posed the most serious threat to the nation or human welfare more generally. -

Security Council Distr.: General 18 July 2007

United Nations S/2007/439 Security Council Distr.: General 18 July 2007 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Abkhazia, Georgia I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1752 (2007) of 13 April 2007, by which the Security Council decided to extend the mandate of the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG) until 15 October 2007. It provides an update of the situation in Abkhazia, Georgia since my report of 3 April 2007 (S/2007/182). 2. My Special Representative, Jean Arnault, continued to lead the Mission. He was assisted by the Chief Military Observer, Major General Niaz Muhammad Khan Khattak (Pakistan). The strength of UNOMIG on 1 July 2007 stood at 135 military observers and 16 police officers (see annex). II. Political process 3. During the reporting period, UNOMIG continued efforts to maintain peace and stability in the zone of conflict. It also sought to remove obstacles to the resumption of dialogue between the Georgian and Abkhaz sides in the expectation that cooperation on security, the return of internally displaced persons and refugees, economic rehabilitation and humanitarian issues would facilitate meaningful negotiations on a comprehensive political settlement of the conflict, taking into account the principles contained in the document entitled “Basic Principles for the Distribution of Competences between Tbilisi and Sukhumi”, its transmittal letter (see S/2002/88, para. 3) and additional ideas by the sides. 4. Throughout the reporting period, my Special Representative maintained regular contact with both sides, as well as with the Group of Friends of the Secretary-General both in Tbilisi and in their capitals. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1992, No.26

www.ukrweekly.com Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.ic, a, fraternal non-profit association! ramian V Vol. LX No. 26 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY0, JUNE 28, 1992 50 cents Orthodox Churches Kravchuk, Yeltsin conclude accord at Dagomys summit by Marta Kolomayets Underscoring their commitment to signed by the two presidents, as well as Kiev Press Bureau the development of the democratic their Supreme Council chairmen, Ivan announce union process, the two sides agreed they will Pliushch of Ukraine and Ruslan Khas- by Marta Kolomayets DAGOMYS, Russia - "The agree "build their relations as friendly states bulatov of Russia, and Ukrainian Prime Kiev Press Bureau ment in Dagomys marks a radical turn and will immediately start working out Minister Vitold Fokin and acting Rus KIEV — As The Weekly was going to in relations between two great states, a large-scale political agreements which sian Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar. press, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church change which must lead our relations to would reflect the new qualities of rela The Crimea, another difficult issue in faction led by Metropolitan Filaret and a full-fledged and equal inter-state tions between them." Ukrainian-Russian relations was offi the Ukrainian Autocephalous Ortho level," Ukrainian President Leonid But several political breakthroughs cially not on the agenda of the one-day dox Church, which is headed by Metro Kravchuk told a press conference after came at the one-day meeting held at this summit, but according to Mr. Khasbu- politan Antoniy of Sicheslav and the conclusion of the first Ukrainian- beach resort, where the Black Sea is an latov, the topic was discussed in various Pereyaslav in the absence of Mstyslav I, Russian summit in Dagomys, a resort inviting front yard and the Caucasus circles. -

Cultural Stereotypes: from Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions Ileana F. Popa Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Ileana Florentina Popa BA, University of Bucharest, February 1991 MA, Virginia Commonwealth University, May 2006 Director: Marcel Cornis-Pope, Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2006 Table of Contents Page Abstract.. ...............................................................................................vi Chapter I. About Stereotypes and Stereotyping. Definitions, Categories, Examples ..............................................................................1 a. Ethnic stereotypes.. ........................................................................3 b. Racial stereotypes. -

The Spread of Christianity in the Eastern Black Sea Littoral (Written and Archaeological Sources)*

9863-07_AncientW&E_09 07-11-2007 16:04 Pagina 177 doi: 10.2143/AWE.6.0.2022799 AWE 6 (2007) 177-219 THE SPREAD OF CHRISTIANITY IN THE EASTERN BLACK SEA LITTORAL (WRITTEN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOURCES)* L.G. KHRUSHKOVA Abstract This article presents a brief summary of the literary and archaeological evidence for the spread and consolidation of Christianity in the eastern Black Sea littoral during the early Christian era (4th-7th centuries AD). Colchis is one of the regions of the late antique world for which the archaeological evidence of Christianisation is greater and more varied than the literary. Developments during the past decade in the field of early Christian archaeology now enable this process to be described in considerably greater detail The eastern Black Sea littoral–ancient Colchis–comprises (from north to south) part of the Sochi district of the Krasnodar region of the Russian Federation as far as the River Psou, then Abkhazia as far as the River Ingur (Engur), and, further south, the western provinces of Georgia: Megrelia (Samegrelo), Guria, Imereti and Adzhara (Fig. 1). This article provides a summary of the literary and archaeological evidence for the spread and consolidation of Christianity in the region during the early Christ- ian era (4th-7th centuries AD).1 Colchis is one of the regions of late antiquity for which the archaeological evidence of Christianisation is greater and more varied than the literary. Progress during the past decade in the field of early Christian archaeology now enables this process to be described in considerably greater detail.2 The many early Christian monuments of Colchis are found in ancient cities and fortresses that are familiar through the written sources.3 These include Pityus (modern Pitsunda, Abkhazian Mzakhara, Georgian Bichvinta); Nitike (modern Gagra); Trakheia, which is surely Anakopiya (modern Novyi Afon, Abkhazian Psyrtskha); Dioscuria/ * Translated from Russian by Brent Davis. -

Improving on Nature: Eugenics in Utopian Fiction

1 Improving on Nature: Eugenics in Utopian Fiction Submitted by Christina Jane Lake to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2017 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright materials and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approve for the award of a degree by this or any other university. (Signature)............................................................................................................. 2 3 Abstract There has long been a connection between the concept of utopia as a perfect society and the desire for perfect humans to live in this society. A form of selective breeding takes place in many fictional utopias from Plato’s Republic onwards, but it is only with the naming and promotion of eugenics by Francis Galton in the late nineteenth century that eugenics becomes a consistent and important component of utopian fiction. In my introduction I argue that behind the desire for eugenic fitness within utopias resides a sense that human nature needs improving. Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859) prompted fears of degeneration, and eugenics was seen as a means of restoring purpose and control. Chapter Two examines the impact of Darwin’s ideas on the late nineteenth-century utopia through contrasting the evolutionary fears of Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872) with Edward Bellamy’s more positive view of the potential of evolution in Looking Backward (1888). -

Knut Hamsun Pan Norsk Pdf

Knut hamsun pan norsk pdf Continue Norwegian novelist Hamsun diverted here. For the film, see Hamsun (film). Knut HamsunKnut Hamsun in July 1939, at the age of 79.BornKnud Pedersen (1859-08-04)August 4, 1859Lom, Gudbrandsdalen, NorwayDiedFebruary 19, 1952(1952-02-19) (92 years old)Nørholm, Grimstad NorwayThe author, poet, screenwriter, social criticNationalityNorwegianPeriod1877-1949The literary movementNeo-romanticismNeo-realismNotable awardsNobel Prize in Literature 1920 Spouses Bergljot Göpfert (née Bech) (189 Marie Hamsun (1909-1952) Children5Signature Knut Hamsun (4 May 1952) 8 1859 – 19 February 1952) as a writer norwegians were awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1920. Hamsun's work lasted more than 70 years and shows changes related to consciousness, themes, perspectives and the environment. He has published more than 20 novels, a collection of poems, several short stories and plays, a travelogue, nonfiction works and several essays. Young Hamsun opposed realism and naturalism. He argues that the main object of modern literature should be the complexity of the human mind, that writers should describe whispers of blood, and begging of the bone marrow. [1] Hamsun was considered the leader of the romantic Neo-Revolt in the early 20th century, with works such as Hunger (1890), Mysteries (1892), Pan (1894) and Victoria (1898). [2] His later works — particularly his Nordland novels — were influenced by Norwegian new realism, depicting everyday life in rural Norway and often using local, ironic and humorous local terms. [3] Hamsun published only one volume of poetry, The Wild Choir, which was set to music by several composers. Hamsun is considered one of the most influential and creative literary stylists for hundreds of years (circa 1890-1990). -

Reviews & Short Features: Vol. 01/ 7 (1916)

REVIEWS OF BOOKS History of Wright County, Minnesota. By FRANKLYN CURTISS- WEDGE. In two volumes. (Chicago, H. C. Cooper Jr. and Company, 1915. xvi, x, 1111 p. Illustrated) History of Renville County, Minnesota. Compiled by FRANKLYN CURTISS-WEDGE, assisted by a large corps of local contrib utors under the direction and supervision of HON. DARWIN S. HALL, HON. DAVID BENSON, and COL. CHARLES H. HOP KINS. In two volumes. (Chicago, H. C. Cooper Jr. and Company, 1916. xix, xiv, 1376 p. Illustrated) History of Otter Tail County, Minnesota; Its People, Industries, and Institutions. JOHN W. MASON, editor. In two volumes. (Indianapolis, B. F. Bowen and Company, 1916. 694, 1009 p. Illustrated) History of Nicollet and Le Sueur Counties, Minnesota; Their People, Industries, and Institutions. HON. WILLIAM G. GRESHAM, editor-in-chief. In two volumes. (Indianapolis, B. F. Bowen and Company, 1916. 544, 538 p. Illustrated) History of Brown County, Minnesota; Its People, Industries, and Institutions. L. A. FRITSCHE, M.D., editor. In two volumes. (Indianapolis, B. F. Bowen and Company, 1916. 519, 568 p. Illustrated) Compendium of History and Biography of Polk County, Minne sota. By MAT. R. I. HOLCOMBE, historical editor, and WIL LIAM H. BINGHAM, general editor. With special articles by various writers. (Minneapolis, W. H. Bingham and Com pany, 1916. 487 p. Illustrated) The writing of county history appears to be a profitable com mercial enterprise. But the value of local history lies not merely in the fact that it may be made the basis of a business under taking. The material with which it deals deserves to be preserved in a permanent and carefully prepared form; for it is nothing less than the whole fascinating story of life, of development, from pioneer days to the present time, restricted, to be sure, to a comparatively small section of the state. -

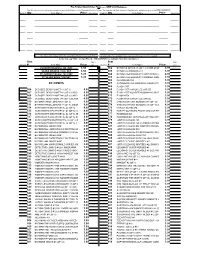

Price Qty X Price Item # Qty Item Name Price Qty X Price

Pre-Printed Short Order Form....…JUNE 2020 Releases Use this section to list any items wanted from any Order Booklet or the Pre-printed list that follows. You can also list Back Issues or Supplies here, and please give us the ITEM NUMBERS! Item # Qty Item Name Price Qty x Price Item # Qty Item Name Price Qty x Price _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ _____ ____ ______________________________________________ _______ Use this section in place of the Previews Order Booklet if you wish. This is merely a list of the more popular items... you can order any item in the catalog! Items that say "NET" are Net Priced... NO DISCOUNT is available from the listed price! Item Qty x Item Qty x Quantity # Item Name Price Price Quantity # Item Name Price Price CURRENT BOARDS ( 100 ) NET 6.50 562 BATMANS GRAVE #8 (OF 12) CARD STOCK R GRAMPA4.99 VAR ED SILVER BOARDS ( 100 ) NET