The Disjunct Coastal Plain Flora in the Great Lakes Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great's Tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, Eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geomorphology 100 (2008) 377–400 www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Alexander the Great's tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, eastern Mediterranean ⁎ N. Marriner a, , J.P. Goiran b, C. Morhange a a CNRS CEREGE UMR 6635, Université Aix-Marseille, Europôle de l'Arbois, BP 80, 13545 Aix-en-Provence cedex 04, France b CNRS MOM Archéorient UMR 5133, 5/7 rue Raulin, 69365 Lyon cedex 07, France Received 25 July 2007; received in revised form 10 January 2008; accepted 11 January 2008 Available online 2 February 2008 Abstract Tyre and Alexandria's coastlines are today characterised by wave-dominated tombolos, peculiar sand isthmuses that link former islands to the adjacent continent. Paradoxically, despite a long history of inquiry into spit and barrier formation, understanding of the dynamics and sedimentary history of tombolos over the Holocene timescale is poor. At Tyre and Alexandria we demonstrate that these rare coastal features are the heritage of a long history of natural morphodynamic forcing and human impacts. In 332 BC, following a protracted seven-month siege of the city, Alexander the Great's engineers cleverly exploited a shallow sublittoral sand bank to seize the island fortress; Tyre's causeway served as a prototype for Alexandria's Heptastadium built a few months later. We report stratigraphic and geomorphological data from the two sand spits, proposing a chronostratigraphic model of tombolo evolution. © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Tombolo; Spit; Tyre; Alexandria; Mediterranean; Holocene 1. Introduction Courtaud, 2000; Browder and McNinch, 2006); (2) establishing a typology of shoreline salients and tombolos (Zenkovich, 1967; The term tombolo is used to define a spit of sand or shingle Sanderson and Eliot, 1996); and (3) modelling the geometrical linking an island to the adjacent coast. -

Types of American Grasses

z LIBRARY OF Si AS-HITCHCOCK AND AGNES'CHASE 4: SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM oL TiiC. CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE United States National Herbarium Volume XII, Part 3 TXE&3 OF AMERICAN GRASSES . / A STUDY OF THE AMERICAN SPECIES OF GRASSES DESCRIBED BY LINNAEUS, GRONOVIUS, SLOANE, SWARTZ, AND MICHAUX By A. S. HITCHCOCK z rit erV ^-C?^ 1 " WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1908 BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Issued June 18, 1908 ii PREFACE The accompanying paper, by Prof. A. S. Hitchcock, Systematic Agrostologist of the United States Department of Agriculture, u entitled Types of American grasses: a study of the American species of grasses described by Linnaeus, Gronovius, Sloane, Swartz, and Michaux," is an important contribution to our knowledge of American grasses. It is regarded as of fundamental importance in the critical sys- tematic investigation of any group of plants that the identity of the species described by earlier authors be determined with certainty. Often this identification can be made only by examining the type specimen, the original description being inconclusive. Under the American code of botanical nomenclature, which has been followed by the author of this paper, "the nomenclatorial t}rpe of a species or subspecies is the specimen to which the describer originally applied the name in publication." The procedure indicated by the American code, namely, to appeal to the type specimen when the original description is insufficient to identify the species, has been much misunderstood by European botanists. It has been taken to mean, in the case of the Linnsean herbarium, for example, that a specimen in that herbarium bearing the same name as a species described by Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum must be taken as the type of that species regardless of all other considerations. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Wild Species 2010 the GENERAL STATUS of SPECIES in CANADA

Wild Species 2010 THE GENERAL STATUS OF SPECIES IN CANADA Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council National General Status Working Group This report is a product from the collaboration of all provincial and territorial governments in Canada, and of the federal government. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 302 pp. Available in French under title: Espèces sauvages 2010: La situation générale des espèces au Canada. ii Abstract Wild Species 2010 is the third report of the series after 2000 and 2005. The aim of the Wild Species series is to provide an overview on which species occur in Canada, in which provinces, territories or ocean regions they occur, and what is their status. Each species assessed in this report received a rank among the following categories: Extinct (0.2), Extirpated (0.1), At Risk (1), May Be At Risk (2), Sensitive (3), Secure (4), Undetermined (5), Not Assessed (6), Exotic (7) or Accidental (8). In the 2010 report, 11 950 species were assessed. Many taxonomic groups that were first assessed in the previous Wild Species reports were reassessed, such as vascular plants, freshwater mussels, odonates, butterflies, crayfishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Other taxonomic groups are assessed for the first time in the Wild Species 2010 report, namely lichens, mosses, spiders, predaceous diving beetles, ground beetles (including the reassessment of tiger beetles), lady beetles, bumblebees, black flies, horse flies, mosquitoes, and some selected macromoths. The overall results of this report show that the majority of Canada’s wild species are ranked Secure. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 8-8-2007 The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands Lon Boudreaux Jr. University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Boudreaux, Lon Jr., "The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We are Failing to Save its Wetlands" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 564. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/564 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mississippi River Delta Basin and Why We Are Failing to Save Its Wetlands A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies By Lon J. Boudreaux Jr. B.S. Our Lady of Holy Cross College, 1992 M.S. University of New Orleans, 2007 August, 2007 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................. -

Subsurface Geology of Cenozoic Deposits, Gulf Coastal Plain, South-Central United States

REGIONAL STRATIGRAPHY AND _^ SUBSURFACE GEOLOGY OF CENOZOIC DEPOSITS, GULF COASTAL PLAIN, SOUTH-CENTRAL UNITED STATES V U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1416-G AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Survey publications re leased prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that may be listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" may no longer be available. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices listed below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books and Maps Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Tech Books and maps of the U.S. Geological Survey are available niques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications over the counter at the following U.S. Geological Survey offices, all of general interest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Docu copies of Earthquakes & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of ments. Epicenters, and some miscellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from ANCHORAGE, Alaska-Rm. -

Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain Region SUMMARY of FINDINGS

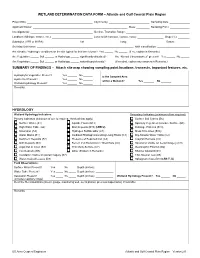

WETLAND DETERMINATION DATA FORM – Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain Region Project/Site: City/County: Sampling Date: Applicant/Owner: State: Sampling Point: Investigator(s): Section, Township, Range: Landform (hillslope, terrace, etc.): Local relief (concave, convex, none): Slope (%): Subregion (LRR or MLRA): Lat: Long: Datum: Soil Map Unit Name: NWI classification: Are climatic / hydrologic conditions on the site typical for this time of year? Yes No (If no, explain in Remarks.) Are Vegetation , Soil , or Hydrology significantly disturbed? Are “Normal Circumstances” present? Yes No Are Vegetation , Soil , or Hydrology naturally problematic? (If needed, explain any answers in Remarks.) SUMMARY OF FINDINGS – Attach site map showing sampling point locations, transects, important features, etc. Hydrophytic Vegetation Present? Yes No Is the Sampled Area Hydric Soil Present? Yes No within a Wetland? Yes No Wetland Hydrology Present? Yes No Remarks: HYDROLOGY Wetland Hydrology Indicators: Secondary Indicators (minimum of two required) Primary Indicators (minimum of one is required; check all that apply) Surface Soil Cracks (B6) Surface Water (A1) Aquatic Fauna (B13) Sparsely Vegetated Concave Surface (B8) High Water Table (A2) Marl Deposits (B15) (LRR U) Drainage Patterns (B10) Saturation (A3) Hydrogen Sulfide Odor (C1) Moss Trim Lines (B16) Water Marks (B1) Oxidized Rhizospheres along Living Roots (C3) Dry-Season Water Table (C2) Sediment Deposits (B2) Presence of Reduced Iron (C4) Crayfish Burrows (C8) Drift Deposits (B3) Recent Iron Reduction -

Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN): a Community Contributed Taxonomic Checklist of All Vascular Plants of Canada, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Greenland

A peer-reviewed open-access journal PhytoKeysDatabase 25: 55–67 of Vascular(2013) Plants of Canada (VASCAN): a community contributed taxonomic... 55 doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.25.3100 DATA PAPER www.phytokeys.com Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN): a community contributed taxonomic checklist of all vascular plants of Canada, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Greenland Peter Desmet1, Luc Brouillet1 1 Université de Montréal Biodiversity Centre, 4101 rue Sherbrooke est, H1X2B2, Montreal, Canada Corresponding author: Peter Desmet ([email protected]) Academic editor: Vishwas Chavan | Received 19 March 2012 | Accepted 17 July 2013 | Published 24 July 2013 Citation: Desmet P, Brouillet L (2013) Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN): a community contributed taxonomic checklist of all vascular plants of Canada, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Greenland. PhytoKeys 25: 55–67. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.25.3100 Resource ID: GBIF key: 3f8a1297-3259-4700-91fc-acc4170b27ce Resource citation: Brouillet L, Desmet P, Coursol F, Meades SJ, Favreau M, Anions M, Bélisle P, Gendreau C, Shorthouse D and contributors* (2010+). Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN). 27189 records. Online at http://data.canadensys.net/vascan, http://dx.doi.org/10.5886/Y7SMZY5P, and http://www.gbif.org/dataset/3f8a1297- 3259-4700-91fc-acc4170b27ce, released on 2010-12-10, version 24 (last updated on 2013-07-22). GBIF key: 3f8a1297-3259-4700-91fc-acc4170b27ce. Data paper ID: http://dx.doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.25.3100 Abstract The Database of Vascular Plants of Canada or VASCAN http://data.canadensys.net/vascan( ) is a comprehen- sive and curated checklist of all vascular plants reported in Canada, Greenland (Denmark), and Saint Pierre and Miquelon (France). -

Recommendations for the Collection and Use of Native Plants

Recommendations for the Collection and Use of Native Plants Native ecosystems can never be replaced. Conservation of remaining plant communities must be considered an important priority because of the many economic, spiritual, medicinal, and sociological values that are associated with them. The genetic diversity of these well adapted ecosystems is also of key importance. All native plant species in any given area should be considered of value to that area. Our ability to reclaim or revegetate areas should never be an excuse for destruction of native plant communities. However, if areas are to be destroyed this presents an opportunity for collection of native plants. This brochure reflects our current understanding of conservation and use of native plants. As we learn more about how plant communities develop and ‘maintain themselves, about the genetics of individuals and populations, and about what succeeds and fails in harvesting, growing, and using native plants, we will continue to update these recommendations. Included in this brochure is a list of further readings that you may find helpful in working with native plants. Know Your Species 1. Know the flora of the area before you collect. Avoid uncommon, rare, or endangered species for that area. 2. Identify plants before collecting seeds or cuttings. 3. Collect from large local populations, both to maximize genetic diversity of your collection and to minimize effects on the natural population. 4. Report occurrences of rare species to: 5. University of Saskatchewan Fraser Herbarium (966-4950); or Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre (787- 7.198). Use Local Genotypes 1. NATIVE: indigenous, originating in a certain place. -

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of the Washington - Baltimore Area

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of the Washington - Baltimore Area Part II Monocotyledons Stanwyn G. Shetler Sylvia Stone Orli Botany Section, Department of Systematic Biology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0166 MAP OF THE CHECKLIST AREA Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants of the Washington - Baltimore Area Part II Monocotyledons by Stanwyn G. Shetler and Sylvia Stone Orli Department of Systematic Biology Botany Section National Museum of Natural History 2002 Botany Section, Department of Systematic Biology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0166 Cover illustration of Canada or nodding wild rye (Elymus canadensis L.) from Manual of the Grasses of the United States by A. S. Hitchcock, revised by Agnes Chase (1951). iii PREFACE The first part of our Annotated Checklist, covering the 2001 species of Ferns, Fern Allies, Gymnosperms, and Dicotyledons native or naturalized in the Washington-Baltimore Area, was published in March 2000. Part II covers the Monocotyledons and completes the preliminary edition of the Checklist, which we hope will prove useful not only in itself but also as a first step toward a new manual for the identification of the Area’s flora. Such a manual is needed to replace the long- outdated and out-of-print Flora of the District of Columbia and Vicinity of Hitchcock and Standley, published in 1919. In the preparation of this part, as with Part I, Shetler has been responsible for the taxonomy and nomenclature and Orli for the database. As with the first part, we are distributing this second part in preliminary form, so that it can be used, criticized, and updated while the two parts are being readied for publication as a single volume. -

A Comparative Study of the Floras of China and Canada

Núm. 24, pp. 25-51, ISSN 1405-2768; México, 2007 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE FLORAS OF CHINA AND CANADA Zhiyao Su College of Forestry, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642 - P. R. China J. Hugo Cota-Sánchez Department of Biology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E2 - Canada E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT at the generic and specific levels that are correlated with more recent geological and In this study, we investigated the floristic climatic variations and ecoenvironment relationships between China and Canada diversity, resulting in differences in floristic based on comparative analysis of their composition. Overall, western and eastern spermatophyte floras. Floristic lists were Canada have a similar number of shared compiled from standard floras and then genera, which suggests multiple migration subjected to cluster analysis using UPGMA events of floristic elements via the Atlantic and NMS ordination methods. Our data and Pacific connections and corridors that demonstrate that the Chinese spermatophyte existed in past geological times. flora is considerably more diverse than that of Canada and that the taxonomic richness Keywords: China, Canada, floristic rela- of seed plants in the floras of China and tionships, taxonomic richness, shared taxa, Canada shows significant variation at the intercontinental disjunction. specific and generic levels. China contains 272 families, 3 318 genera, and 27 078 RESUMEN species (after taxonomic standardization), whereas the spermatophyte flora of Canada En este estudio se investigaron la relaciones includes 145 families, 947 genera, and florísticas entre Canadá y China basados 4 616 species. The results indicate that out en análisis comparativos de las floras de of 553 genera shared by the Chinese and espermatofitas de ambos países.