Thomas (Sunshine Dorothy) Et Al V Davis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant V. Woods, 176 Mass. 492; Vegelahn V. Guntner, 167 Id. 92, Where an Unbroken Line of Authorities Reiterates the Doctrine That COMMENT

YALE LAW JOURNAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE, $2.50 A YEAR. SINGLE COPIES, 35 CENTS EDITORS: JoHN H. SEARs, Chairman. ERNEST T. BAUER, Louis M. ROSENBLUTH, COGSwELL BENTLEY, ROBERT H. STRAHAN, JOHN J. FISHER, KiNsLEY TWINING. Associate Editors: JAMES L LooMIs, CH.maLES C. Russ. WnIJtAi M. MALTBIL CAMERON B. WATERMAN, Business Manager. CHARLES DRIvER FRANCIS, Assistant Business Manager. FRANK KENNA, Assistant Business Manager. Published monthly during the Academic year. by students of the Yale Law School. P. 0. Address, Box 835, Yale Station, New Haven, Conn. If a subscriber wishes his copy of the JOURNAL discontinued at the expiration of his subscription, notice to that effect should be sent; otherwise it is assumed that a con- tinuation of the subscription is desired. COMPETITION AS JUSTIFICATION FOR INTERFERENCE WITH EMPLOY- PLOYMENT OF FELLOW WORKMAN. That, in the absence of justification, it is actionable to induce an employer by a strike or a threatened strike to discharge or refuse to employ a workman, has been repeatedly held. But notwith- standing many such cases in recent years presenting the question as to within what limits a strike, involving no acts tortious per se, may be justified by labor as legitimate competition, the boundary lines remain unmarked. In a large and increasing proportion of these cases the presence or absence of justification must depend upon the object of conduct. The question. has recently arisen in Pennsylvania in the case of Erdman v. Mitchell, 56 Atl. 334, which was an action by one labor union against another to enjoin the latter from attempting by strikes or threatened strikes to prevent members of the former from securing or continuing in employment because of their refusal to join the latter union. -

Malice in Tort

Washington University Law Review Volume 4 Issue 1 January 1919 Malice in Tort William C. Eliot Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William C. Eliot, Malice in Tort, 4 ST. LOUIS L. REV. 050 (1919). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol4/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MALICE IN TORT As a general rule it may be stated that malice is of no conse- quence in an action of tort other than to increase the amount of damages,if a cause of action is found and that whatever is not otherwise actionable will not be rendered so by a malicious motive. In the case of Allen v. Flood, which is perhaps the leading one on the subject, the plaintiffs were shipwrights who did either iron or wooden work as the job demanded. They were put on the same piece of work with the members of a union, which objected to shipwrights doing both kinds of work. When the iron men found that the plaintiffs also did wooden work they called in Allen, a delegate of their union, and informed him of their intention to stop work unless the plaintiffs were discharged. As a result of Allen's conference with the employers plaintiffs were discharged. -

Authority of Allen V. Flood

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 1902 Authority of Allen v. Flood Horace LaFayette Wilgus University of Michigan Law School Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/9 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Courts Commons, Judges Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Wilgus, Horace LaFayette. "Authority of Allen v. Flood." Mich. L. Rev. 1 (1902): 28-57. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AUTHORITY OF ALLEN V. FLOOD' N THE case of Allen v. Flood,' one of the Lords asked this interesting question, "If the cook says to her master, 'Dis- charge the butler or I leave you,' and the master discharges the butler, does the butler have an action against the cook?"' This, Lord Shand said, was the simplest form in which the very question in Allen v. Flood could be raised.4 And, like the original question, it puzzled the judges and Lords very much to answer. Cave, J. answers,, Yes:- "Ex concessis, the butler has been interfered with in earning his livelihood and has lost his situation, and the circumstances shew no just cause or ex- cuse why the cook should have induced her master to discharge the butler; .. -

A Defence of Duress in the Law of Torts?

A defence of duress in the law of torts? James Edelman and Esther Dyer Paper presented at The Limits of Liability: Defences in Tort Law All Souls College, Oxford 10-11 January 2014 Contents Introduction: the dominant view in English law ........................................................................ 2 (1) The limited authority against a tortious defence of duress ................................................... 4 (2) A defence of duress in the law of torts by analogy with the criminal law ............................ 6 (i) Tortious liability based on duress was developed by analogy with the criminal law ........ 7 (3) Overlap between a defence of necessity and a defence of duress....................................... 15 (i) Necessity in criminal law ................................................................................................. 15 (ii) Necessity in the law of torts............................................................................................ 16 (iii) The lack of a clear distinction between necessity and duress........................................ 19 (4) The theoretical basis for recognition of a defence of duress .............................................. 21 (i) The objection that a defence of duress is inconsistent with the goal of the law of torts . 21 (ii) The objection that duress involves unwarranted erosion of the claimant's right ............ 24 (a) The argument: duress as a defence operates to negate intention and this is unjustifiable ..................................................................................................................... -

Mark Aronson*

McGill Law Journal ~ Revue de droit de McGill SOME AUSTRALIAN REFLECTIONS ON RONCARELLI V. DUPLESSIS Mark Aronson* Roncarelli v. Duplessis figures far more En Australie, l’affaire Roncarelli c. Du- frequently in Australia’s secondary literature plessis est plus souvent traitée dans la doctrine than in its court decisions, and it is noted not que dans la jurisprudence. Elle est connue non for its invalidation of Prime Minister Du- pas pour son invalidation des actes du Premier plessis’s actions, but for its award of damages ministre Duplessis, mais pour son octroi de where judicial declaration of invalidity would dommages-intérêts dans une situation où une usually be the only remedy. Invalidating Du- déclaration judiciaire d’invalidité aurait norma- plessis’s interference with Roncarelli’s liquor li- lement constitué le seul recours possible. Si la cence would have been the easy part of the case cause avait été entendue en Australie, had it been tried in Australia. Australian stat- l’invalidation de l’interférence de Duplessis au- utes afforded good protection to liquor licensees, rait été une question facile à résoudre. Les lois and general administrative law principles con- australiennes offraient une forte protection aux fined seemingly unfettered discretionary powers détenteurs de permis d’alcool et les principes du in less solicitous statutory regimes. In addition, droit administratif confinaient les pouvoirs dis- the constitutional abolition of internal trade crétionnaires sans entraves aux régimes statu- barriers used to be taken as banning unfettered taires d’intérêt moindre. De plus, l’abolition regulatory powers over interstate traders. constitutionnelle des obstacles au commerce in- Duplessis’s tort liability was the hard part. -

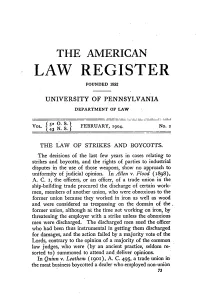

The Law of Strikes and Boycotts

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER FOUNDED 1852 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF LAW VOL. 52 0 S FEBRUARY,F 1904. No.2 43 N. S. __ THE LAW OF STRIKES AND BOYCOTTS. The decisions of the last few years in cases relating to strikes and boycotts, and the rights of parties to industrial disputes in the use of those weapons, show no approach to uniformity of judicial opinion. In Allen v. Flood (1898), A. C. i, the officers, or an officer, of a trade union in the ship-building trade procured the discharge of certain work- men, members of another union, who were obnoxious to the former union because they worked in iron as well as wood and were considered 'as trespassing on the domain of the. former union, although at the time not working on iron, by threatening the employer with a strike unless the obnoxious men were discharged. The discharged men sued the officer who had been thus instrumental in getting them discharged for damages, and the action failed by a majority vote of the Lords, contrary to the opinion of a majority of the common law judges, who were (by an ancient practice, seldom re- sorted to) summoned to attend and deliver opinions. In Quinn v. Lcathen (i9oI), A. C. 495, a trade union in the meat business boycotted a dealer who employed non-union 73 THE LAW OF STRIKES AND BOYCOTTS. men and refused to discharge them, and induced one of his customers to stop buying of him by threatening to bring on a strike among the customer's workmen. -

Part III--The Conspiracy and Tort Foundations of the Labor Injunction Sylvester Petro

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 60 | Number 3 Article 3 3-1-1982 Unions and the Southern Courts: Part III--The Conspiracy and Tort Foundations of the Labor Injunction Sylvester Petro Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sylvester Petro, Unions and the Southern Courts: Part III--The Conspiracy and Tort Foundations of the Labor Injunction, 60 N.C. L. Rev. 543 (1982). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol60/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIONS AND THE SOUTHERN COURTS: PART III-THE CONSPIRACY AND TORT FOUNDATIONS OF THE LABOR INJUNCTION SYLVESTER PETRO TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................ 544 II. CONSPIRACY, THE PHANTOM TORT ............................ 546 III. THE "LAWFUL IN ITSELF" THEORY OF TORTS .................. 558 A. Allen v. Flood andActs 'Lawful in Themselves". .......... 558 B. 4 Critique of Allen v. Flood and the "Lawful in Itself" D octrine .................................................. 567 IV. THE PRIMA FACIE TORT THEORY AND THE JUST-CAUSE PRINCIPLE .................................................... 574 A. Malice in Fact, Malice in Law, andFreedom ............... 575 B. National Protective Association of Steam Fitters v. Cumming: A Travesty of the Just-CausePrinc#le .......... 587 C Benefit to Defendant Rather than Harm to Plaintffas "Primary"M otive ......................................... 593 D. Self-Interest as a Ground of Just'fcation: The "FreeStruggle for Life" . ................................................ 595 E. Competition, The Unseen Hand ........................... -

Imagereal Capture

Of Principle and Prima Facie Tort CHRISTIAN WITTING* INTRODUCTION This article considers the difficulty experienced by American courts in attempting to translate a general tort principle underpinning various inten- tional tort actions derived from the action on the case into a free-standing tort itself. The principle in question, termed the 'harm principle',' recognises that the intentional infliction of injury without just cause or excuse is tortious. It was formulated by Lord Justice Bowen in Mogul Steamship Co v McGregor Gow and Co2, but the House of Lords in Bradford v Pickles3 and in Allen v Flood4 viewed actual intention as irrelevant to tortious liability and refused to adopt it. The principle commended itself, however, to academic commentators and Oliver Wendell Holmes assisted in enshrining it into Massachusetts law? From there, it was adopted by a small number of other American jurisdictions and applied as the 'prima facie tort'. The operation of the prima facie tort has been severely restricted by a number of limitations designed primarily to prevent it from 'undermining' established intentional torts. This has followed criticism that the tort is too amorphous in nature and not capable of a consistent and satisfactory appli- cation. However, it is submitted that the doctrine is a sound one, taking the presence of an intention to harm as central to the imposition of liability. The presence of such intention is an important moral factor in any liability que~tion.~Having said that, courts adopting the tort must be fairly specific in determining what are to be the limits of liability. Those limits will be determined by reference to overall patterns of liability in tort. -

Mental Element in Tort

2020 LAW OF TORT Ms. RUBI SCHOOL OF LAW MONAD UNIVERSITY HAPUR NAME OF TEACHER Rubi MOB. NO. 8755544779 E MAIL ID [email protected] DESIGNATION Assistant Professor UNIVERSITY NAME Monad University, Hapur. COLLEGE NAME Monad School of Law. STREAM NAME Law FACULTY NAME Law DEPARTMENT NAME Law SUBJECT NAME Law of Tort COURSE LL.B & B.A.LL.B. 1 Sem & 3 Sem COURSE DURATION 3 & 5 Years Unit II nd SUBTOPIC NAME Mental Element in Tort CONTENT TYPE Text SEARCH KEYWORD Mental Element in Tort RUBI (CONTENT CREATER/TEACHER) Unit – 2 Part - 2 Syllabus General Condition of Liability in Tort: Wrongful Act Legal Damage Damnum sine Injuria Unit- Injuria sine Damnum II Legal Remedy- Ubi jus ibi remedium Mental Element in Tort Motive, Intention, Malice and its Kinds Trespass Mental Element in Tort Motive, Intention, Malice and its Kinds Motive A motive is a person’s state of mind that inspires him to do an act. It usually means the purpose of the act’s commission. Motive is generally irrelevant in tort law, just like intention. Motive leads to intention formation, which is the ultimate cause. Motive is the ultimate object with which an act is done, while the immediate purpose is the intention. The cause that moves individuals to induce a certain action is a motive, in law, especially criminal law. Typically, the legal system allows motive to be proven to make plausible reasons for committing a crime for the accused. However, motive is not essential for a tort action to be maintained. It is not just because the motive is good that a wrongful act becomes legal. -

1453025170 Quinn V Leathem 1901 UKHL 2

6/12/2015 Quinn v Leathem [1901] UKHL 2 (05 August 1901) [Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback] United Kingdom House of Lords Decisions You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom House of Lords Decisions >> Quinn v Leathem [1901] UKHL 2 (05 August 1901) URL: http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1901/2.html Cite as: [1901] AC 495, [1901] UKHL 2 [New search] [Buy ICLR report: [1901] AC 495] [Help] JISCBAILII_CASE_TORT BAILII Citation Number: [1901] UKHL 2 HOUSE OF LORDS Date: 05 August 1901 Between: QUINN APPELLANT v LEATHEM RESPONDENT The House took time for consideration. Aug. 5. EARL OF HALSBURY L.C. My Lords, in this case the plaintiff has by a properly framed statement of claim complained of the defendants, and proved to the satisfaction of a jury that the defendants have wrongfully and maliciously induced customers and servants to cease to deal with the plaintiff, that the defendants did this in pursuance of a conspiracy framed among them, that in pursuance of the same conspiracy they induced servants of the plaintiff not to continue in the plaintiff's employment, and that all this was done with malice in order to injure the plaintiff, and that it did injure the plaintiff. If upon these facts so found the plaintiff could have no remedy against those who had thus injured him, it could hardly be said that our jurisprudence was that of a civilized community, nor indeed do I understand that any one has doubted that, before the decision in Allen v. Flood(1) in this House, such fact would have established a cause of action against the defendants. -

The Economic Torts and English Law: an Uncertain Future

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 95 | Issue 4 Article 3 2007 The conomicE Torts and English Law: An Uncertain Future Hazel Carty Manchester University Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Common Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Carty, Hazel (2007) "The cE onomic Torts and English Law: An Uncertain Future," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 95 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol95/iss4/3 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES The Economic Torts and English Law: An Uncertain Future Hazel Carty' I. INTRODUCTION A. The Economic Torts Outlined There is no over-arching tort of unfair competition or misappropriation in English common law. Rather, when excessive competitive practices are al- leged, the aggrieved party must identify a specific tort (or torts) that cover the harm done to them. The causes of action most appropriate where unfair trading is the issue are the so-called "economic torts."' These causes of action comprise the torts of simple conspiracy, unlawful conspiracy, induc- ing breach of contract, intimidation, unlawful interference with trade, and malicious falsehoodA The list also includes the important tort of passing off which, unlike the others, is not a tort of intention. -

Shifting Blame? Reassessing the Tort of Inducing Breach of Contract Following A.I

Shifting Blame? Reassessing the Tort of Inducing Breach of Contract Following A.I. Enterprises v. Bram * BROOKE MACKENZIE I. INTRODUCTION The tort of inducing breach of contract has never truly come into its own in Canadian law. Although it has formed a part of our common law for over 150 years, it remains a product of the particular social and economic conditions surrounding its recognition under English law in 1853. To date, its elements have never been conclusively settled in Canada, and the rationale for the tort's existence remains unclear. Following the Supreme Court of Canada's decision in Bram Enterprises Ltd. v. A.I. Enterprises Ltd.1 respecting the related tort of causing loss by unlawful means, it is high time to critically assess the tort of inducing breach of contract, and whether its recognition can be justified by Canadian common law in our modern economy. In particular, the Supreme Court's statements in A.I. Enterprises respecting the limited role of the common law in regulating commercial conduct suggest that if the tort is to play any role in Canadian law moving forward, it must be narrowly defined. Courts have recently explained inducing breach of contract as a tort of ``accessory liabilityº, shifting responsibility for a breach of contract from the breaching party to a stranger to the contract who procured the breach. This purported justification leaves something to be desired Ð it is not only at odds with the doctrine of privity of contract and the theory of corrective justice, but it fails to adequately explain the overlapping yet divergent spheres of liability attributed to each of the breaching party and inducer.