Pain in Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha)

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Ihsan Ali Muhammad Naeem Qazi Hazara University Mansehra NWFP – Pakistan 2008 Uploaded by [email protected] © Copy Rights reserved in favour of Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Editors: Ihsan Ali* Muhammad Naeem Qazi** Price: US $ 20/- Title: Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Frontispiece: Buddha Visiting Kashyapa Printed at: Khyber Printers, Small Industrial Estate, Kohat Road, Peshawar – Pakistan. Tel: (++92-91) 2325196 Fax: (++92-91) 5272407 E-mail: [email protected] Correspondence Address: Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Website: hu.edu.pk E-mail: [email protected] * Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Currently Vice Chancellor, Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan ** Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan CONTRIBUTORS 1. Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, Vice Chancellor Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 2. Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 3. Ihsanullah Jan, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 4. Muhammad Ashfaq, University Museum, Hazara University 5. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 6. Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 7. Muhammad Imran Khan, Archaeologist, Charsadda, Pakistan 8. Muhammad Haroon, Archaeologist, Mardan, Pakistan III ABBREVIATIONS A.D.F.C. Archaeology Department, Frontier Circle A.S.I. Archaeological Survery of India A.S.I.A.R. Archaeological Survery of India, Annual Report D.G.A. Director General of Archaeology E.G.A.C. Exhibition of the German Art Council I.G.P. Inspector General Police IsMEO Instituto Italiano Per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente P.M. -

Index of Places

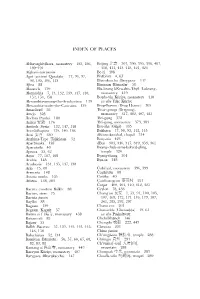

INDEX OF PLACES Abhayagirivihra, monastery 185, 186, Beijing 北京 307, 390, 395, 396, 407, 189–191 410, 411, 413–418, 421, 424 Afghanistan passim Be-ri 408 Agni (ancient Qaraahr) 77, 94, 97, Bhbhr 4, 63 98, 105, 106, 113 Bharukaccha (Barygaza) 147 Aúina 88 Bimaran (Bimarn) 58 Alasanda 139 Bla-brang bKra-shis-’khyil (Labrang), Alexandria 7, 13, 132, 139, 147, 148, monastery 419 152, 154, 158 Boda-yin Küriye, monastery 418 Alexandria-among-the-Arachosians 139 see also Yeke Küriye Alexandria-under-the-Caucasus 139 Brag-lha-mo (Drag Lhamo) 305 Amarvat 58 ’Bras-spungs (Drepung), Amdo 328 monastery 317, 402, 407, 425 Undhra Prade 180 ’Bri-gung 372 Anhui 安徽 176 ’Bri-gung, monastery 373, 383 Antioch (Syria) 132, 147, 148 Bru-sha (Gilgit) 335 Anurdhapura 139, 140, 186 Bukhara 77, 90, 93, 142, 145 Anxi 安西 330 dBu-ru-ka-tshal, chapel 314 Anzhina-Tepe (Tajikistan) 52 Buryatia 423 Aparntaka 138 dBus 304, 346, 347, 349, 353, 361 Aparaaila 40 Byang-chub-sems-bskyed-gling, Apraca 55, 62 temple 324 Aqsu 77, 107, 108 Byang-thang 304 Arabia 148 Bya-sa 348 Arachosia 134, 135, 137, 138 Aria 75, 80 ab iyal, monastery 396, 399 Armenia 148 anyn 88 Astana tombs 105 Caitika 40 Athens 148, 203 Caizhuangcun 蔡莊村 221 aqar 400, 401, 410, 412, 425 Bactres (modern Balkh) 88 Ceylon 78, 436 Bactres, river 75 Chang’an 長安 1, 53, 91, 100, 105, Bactria passim 107, 168, 172, 174–176, 179, 187, Baln 88 261, 285, 292, 297 Bagrm 139 Characene 203 Begram (Kap ) 57 Charsadda (Charsa a) 49, 61 Baima si 白馬寺, monastery 438 see also Pukalvat Bairam-ali 83 Chehelkhneh 146 Bajaur 55 Chengdu -

Posthumous Azes Coins in Stupa Deposits from Ancient Afghanistan

Posthumous Azes Coins In stupa deposits from ancient Afghanistan ONS 2 March 2013 ‘Donation of Śivarakṣita, son of Mujavada, offered with relics of the Lord, in honour of all buddhas’ Deposits from Bimaran 2 stupa with the gold casket and Posthumous Azes coins Courtesy of Piers Baker Shevaki Stupa, Kabul Courtesy of Piers Baker Shevaki Stupa from afar Courtesy of Piers Baker Guldara Stupa, Kabul The ‘Indo-Scythians’ kings and satraps in coin sequences (Based on Errington & Curtis 2007) Kings Satraps Basileos / Maharaja Satrap, Strategos / Chatrap Maues (c.75-65BC) Kharahostes (early 1st AD) Vonones (c.65-50BC) Zeionises (c.AD30-50) Spalyrises (c.50-40BC) Rajavula Azes I (c.46-1BC) Aspavarma (c.AD33-64)* Azilises (c.1BC-AD16) * With the name ‘Azes’ on the obverse Azes II (c.16-30AD) Indo-Scythian coins from Buddhist sites in ancient Pakistan and Afghanistan (Based on Errington 1999/2000) Swat Darunta/Jalalabad/ Peshawar Hadda Taxila Posthumous Azes Maues c.75-65BC Azilises c.1BC-AD16 Zeionises c.AD30-50 Vonones c.65-50BC Azes II c.AD16-30 Rajavula Azes I c.46-1BC Kharahostes early 1st AD Aspavarma c.AD33-64 Pontic to Central Asian steppes Iranian Plateau Arabia Nomadic and sedentary groups living in areas extending from the Pontic to Central Asian steppes during the first millennium BC ‘Σκυϑοι’ in Greek sources / ‘Sakas’ in Iranian sources ‘Śakas’ in Indian sources / ‘Sai’ or ‘Se’ in Chinese sources Three types of Sakas according to the Naqš-i-Rustam inscription of Darius I Sakas ‘who are across the sea’ (Saka Paradraya) The Pontic steppe -

Catalog and Revised Texts and Translations of Gandharan Reliquary Inscriptions

Chapter 6 Catalog and revised texts and translations of gandharan reliquary inscriptions steFan baums the Gandharan reliquary inscriptions cataloged and addition to or in place of these main eras, regnal translated in this chapter are found on four main types years of a current or (in the case of Patika’s inscrip- of objects: relic containers of a variety of shapes, thin tion no. 12) recent ruler are used in dating formulae, gold or silver scrolls deposited inside reliquaries, and detailed information is available about two of the thicker metal plates deposited alongside reliquaries, royal houses concerned: the kings of Apraca (family and stone slabs that formed part of a stūpa’s relic tree in Falk 1998: 107, with additional suggestions in chamber or covered stone reliquaries. Irrespective Salomon 2005a) and the kings of Oḍi (family tree in of the type of object, the inscriptions follow a uniform von Hinüber 2003: 33). pattern described in chapter 5. Three principal eras In preparing the catalog, it became apparent that are used in the dating formulae of these inscriptions: not only new and uniform translations of the whole the Greek era of 186/185 BCE (Salomon 2005a); the set of inscriptions were called for, but also the texts Azes (= Vikrama) era of 58/57 BCE (Bivar 1981b);1 themselves needed to be reconstituted on the basis and the Kanishka era of c. 127 CE (Falk 2001). In of numerous individual suggestions for improvements made after the most recent full edition of each text. All these suggestions (so far as they could be traced) 1. -

The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads

The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Departments of Archaeology and History (joint) By Paul Wilson Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2020 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. 1 Abstract: The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads The Kushans were a major historical power on the ancient Silk Roads, although their influence has been greatly overshadowed by that of China, Rome and Parthia. That the Kushans are so little known raises many questions about the empire they built and the role they played in the political and cultural dynamics of the period, particularly the emerging Silk Roads network. Despite building an empire to rival any in the ancient world, conventional accounts have often portrayed the Kushans as outsiders, and judged them merely in the context of neighbouring ‘superior’ powers. By examining the materials from a uniquely Kushan perspective, new light will be cast on this key Central Asian society, the empire they constructed and the impact they had across the region. Previous studies have tended to focus, often in isolation, on either the archaeological evidence available or the historical literary sources, whereas this thesis will combine understanding and assessments from both fields to produce a fuller, more deeply considered, profile. -

Numismatic Evidence and the Date of Kaniṣka I ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Joe Cribb

Rienjang W. (ed.) 2018. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art. p7-34. Archaeopress Archaeology. DOI: 10.32028/9781784918552P7-34. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017 Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Archaeopress Archaeology Rienjang W. (ed.) 2018. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art. p7-34. Archaeopress Archaeology. DOI: 10.32028/9781784918552P7-34. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 855 2 ISBN 978 1 78491 856 9 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Rienjang W. (ed.) 2018. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art. p7-34. Archaeopress Archaeology. DOI: 10.32028/9781784918552P7-34. Contents Acknowledgements ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Note on orthography ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Contributors �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii -

Kaniṣka's Buddha Coins – the Official Iconography of Śākyamuni

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A. K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS Heinz Bechert Leon Hurvitz Universitdt Gottingen, FRG UBC, Vancouver, Canada Lewis Lancaster Alexander W. MacDonald University of California, Berkeley, USA Universite de Paris X, Nanterre, France B.J. Stavisky Alex Way man WNIIR, Moscow, USSR Columbia University, New York, USA ASSOCIATE EDITOR Stephan Beyer University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA Volume 3 1980 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. A Yogacara Analysis of the Mind, Based on the Vijndna Section of Vasubandhu's Pancaskandhaprakarana with Guna- prabha's Commentary, by Brian Galloway 7 2. The Realm of Enlightenment in Vijnaptimdtratd: The Formu lation of the "Four Kinds of Pure Dharmas", by Noriaki Hakamaya, translated from the Japanese by John Keenan 21 3. Hu-Jan Nien-Ch'i (Suddenly a Thought Rose) Chinese Under standing of Mind and Consciousness, by Whalen Lai 42 4. Notes on the Ratnakuta Collection, by K. Priscilla Pedersen 60 5. The Sixteen Aspects of the Four Noble Truths and Their Opposites, by Alex Wayman 67 II. SHORT PAPERS 1. Kaniska's Buddha Coins — The Official Iconography of Sakyamuni & Maitreya, by Joseph Cribb 79 2. "Buddha-Mazda" from Kara-tepe in Old Termez (Uzbekistan): A Preliminary Communication, by Boris J. Stavisky 89 3. FausbpU and the Pali Jatakas, by Elisabeth Strandberg 95 III. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Love and Sympathy in Theravada Buddhism, by Harvey B. Aronson 103 2. Chukan to Vuishiki (Madhyamika and Vijriaptimatrata), by Gadjin Nagao 105 3. Introduction a la connaissance des hlvin bal de Thailande, by Anatole-Roger Peltier 107 4. -

Charles Masson and the Buddhist Sites of Afghanistan Company to Explore the Ancient Sites in South-East Afghanistan

From 1833–8, Charles Masson (1800–1853) was employed by the British East India Charles Masson and the Buddhist Sites of Afghanistan Company to explore the ancient sites in south-east Afghanistan. During this period, he surveyed over a hundred Buddhist sites around Kabul, Jalalabad and Wardak, making numerous drawings of the sites, together with maps, compass readings, sections of the stupas and sketches of some of the finds. Small illustrations of a selection of these key sites were published in Ariana Antiqua in 1841. However, this represents only a tiny proportion of his official and private correspondence held in the India Office Collection of the British Library which is studied in detail in this publication. It is supplemented online by The Charles Masson Archive: British Library and British Museum Documents Relating to the 1832–1838 Masson Collection from Afghanistan (British Museum Research Publication number 216). Together they provide the means for a comprehensive reconstitution of the archaeological record of the sites. In return for funding his exploration of the ancient sites of Afghanistan, the British East India Company received all of Masson’s finds. These were sent to the India Museum in London, and when it closed in 1878 the British Museum was the principal recipient of all the ‘archaeological’ artefacts and a proportion of the coins. This volume studies the British Museum’s collection of the Buddhist relic deposits, including reliquaries, beads and coins, and places them within a wider historical and archaeological context for the first time. Masson’s collection of coins and finds from Begram are the subject of a separate study. -

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Editors:Editors:Editors: Ihsan Ali*

Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Editors:Editors:Editors: Ihsan Ali* Muhammad Naeem Qazi** Price: US $ 20/- Title:Title:Title: Gandharan Sculptures in the Peshawar Museum (Life Story of Buddha) Frontispiece: Buddha Visiting Kashyapa Correspondence Address: Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan Website: hu.edu.pk E-mail: [email protected] * Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Currently Vice Chancellor, Hazara University, Mansehra, NWFP – Pakistan ** Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan CONTRIBUTORS 1. Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, Vice Chancellor Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan 2. Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 3. Ihsanullah Jan, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 4. Muhammad Ashfaq, University Museum, Hazara University 5. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, Pakistan 6. Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Lecturer, Department of Cultural Heritage & Tourism Management, Hazara University 7. Muhammad Imran Khan, Archaeologist, Charsadda, Pakistan 8. Muhammad Haroon, Archaeologist, Mardan, Pakistan III ABBREVIATIONS A.D.F.C. Archaeology Department, Frontier Circle A.S.I. Archaeological Survery of India A.S.I.A.R. Archaeological Survery of India, Annual Report D.G.A. Director General of Archaeology E.G.A.C. Exhibition of the German Art Council I.G.P. Inspector General Police IsMEO Instituto Italiano -

Book Review: Kurt A. Behrendt: the Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 27 Number 1 2004 David SEYFORT RUEGG Aspects of the Investigation of the (earlier) Indian Mahayana....... 3 Giulio AGOSTINI Buddhist Sources on Feticide as Distinct from Homicide ............... 63 Alexander WYNNE The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature ................ 97 Robert MAYER Pelliot tibétain 349: A Dunhuang Tibetan Text on rDo rje Phur pa 129 Sam VAN SCHAIK The Early Days of the Great Perfection........................................... 165 Charles MÜLLER The Yogacara Two Hindrances and their Reinterpretations in East Asia.................................................................................................... 207 Book Review Kurt A. BEHRENDT, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara. Handbuch der Orientalistik, section II, India, volume seventeen, Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2004 by Gérard FUSSMAN............................................................................. 237 Notes on the Contributors............................................................................ 251 BOOK REVIEW Kurt A. BEHRENDT, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara, Handbuch der Orien- talistik, section II, India, volume seventeen, Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2004, ISBN 90-04-11595-2 (also written 90 04 13595 2). I am used to reading bad books with pretentious titles, but seldom till now (and I am 64 years old) with such amazement and growing indignation. Amazement, because here is a book which, by its lack of methodology and basic knowledge, pushes back this subject by more than one hundred years. Indignation because being published in a well known series, till now renowned for its scholarly stan- dards, it will become easily available, somewhat popular, deceive all the beginners and give our colleagues not specializing in this field a wrong and outdated impres- sion of the standards we usually achieve. To say it in a few words, this is not a handbook, but a Ph.D. -

Janice Stargardt & Michael Willis (Eds), Relics and Relic Worship in Early Buddhism: India, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Burm

BOOK REVIEW Janice Stargardt & Michael Willis (eds), Relics and Relic Worship in Early Buddhism: India, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Burma. 2018, 123 pp., £35, The British Museum, London. Reviewed by Wannaporn Rienjang This handsome volume takes a holistic approach to the study of Buddhist relics. It brings together seven experts from different fields -- literature and epigraphy, numismatics, art history, material culture studies and archaeology -- to explore how Buddhist relics were perceived and venerated during the period between the turn of the Common Era and about the seventh century AD. As Janice Stargardt says in her introduction, Peter Skilling sets out the theme of the book by highlighting the centrality of relics in Buddhist rituals and ideology. In so doing, he presents textual, epigraphic, architectural and sculptural examples from early to later periods to show how Buddha relics have been treated as the Buddha himself and how they travelled with his teachings. Skilling also emphasizes the role of relics in the historiography of Buddhism in South Asia. He warns that relics should not be studied as mere ‘material culture’, a contention which resonates with the contents of this volume as well as the study of relics in recent decades. The literary context of relics is specially explored by Lance Cousins, who passed away before the book saw its publication. Cousins uses his expertise in Pali literature to discuss the etymology of the words cetiya and thūpa as recorded in canonical and paracanonical Pali texts. While advocating the antiquity of Buddhist Pali texts, Cousins suggests that only in later Pali texts do the meanings of cetiya and thūpa conform to the Buddhist use: they then do not simply mean mound or heap, as they did earlier, but also the places where the worship of relics took place. -

The Masson Project at the British Museum

> Theme Silver coin found at Mir Zakah with the image of the Indo- Greek King, Menan- der (155 BC) holding a spear. The Greek legend gives his Afghanistan: name and title (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENAN- DROU). This king debated on issues of the Buddhist faith Picking up with the monk Nagasena, according to the early Buddhist text Milindapañha, ‘Questions of Milin- da’ (=Menander). the Pieces Formerly Kabul Museum. SPACH. of courtesy Powell, Josephine Ancient Afghanistan through the Eyes of Charles Masson (1800-1853): dols, and the wartime the and dols, The Masson Project at the British Museum In the 1930s, the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan found unexpected evi- Research > dence of an earlier European visitor scribbled in one of the caves above the 55 m Buddha at Afghanistan Bamiyan. This stated: If any fool this high samootch explore hout Afghanistan are now gone, perhaps forever, many forever, perhaps gone, now are Afghanistan hout Know Charles Masson has been here before ce. With each opened box, we marveled at the beauty of the of beauty the at marveled we box, opened each With ce. y lost to the world for the stories they can tell us of humani- of us tell can they stories the for world the to lost y owledge passed on from father to son of how to create them create to how of son to father from on passed owledge s from the City of Rob written in the local Bactrian language Bactrian local the in written Rob of City the from s ything on Afghanistan would wade into the mire of political of mire the into wade would Afghanistan on ything llected on his travels through Afghanistan during the 1830s.