Land Use Demonstration Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copeland Unclassified Roads - Published January 2021

Copeland Unclassified Roads - Published January 2021 • The list has been prepared using the available information from records compiled by the County Council and is correct to the best of our knowledge. It does not, however, constitute a definitive statement as to the status of any particular highway. • This is not a comprehensive list of the entire highway network in Cumbria although the majority of streets are included for information purposes. • The extent of the highway maintainable at public expense is not available on the list and can only be determined through the search process. • The List of Streets is a live record and is constantly being amended and updated. We update and republish it every 3 months. • Like many rural authorities, where some highways have no name at all, we usually record our information using a road numbering reference system. Street descriptors will be added to the list during the updating process along with any other missing information. • The list does not contain Recorded Public Rights of Way as shown on Cumbria County Council’s 1976 Definitive Map, nor does it contain streets that are privately maintained. • The list is property of Cumbria County Council and is only available to the public for viewing purposes and must not be copied or distributed. -

County Durham Plan (Adopted 2020)

County Durham Plan ADOPTED 2020 Contents Foreword 5 1 Introduction 7 Neighbourhood Plans 7 Assessing Impacts 8 Duty to Cooperate: Cross-Boundary Issues 9 County Durham Plan Key Diagram and Monitoring 10 2 What the County Durham Plan is Seeking to Achieve 11 3 Vision and Objectives 14 Delivering Sustainable Development 18 4 How Much Development and Where 20 Quantity of Development (How Much) 20 Spatial Distribution of Development (Where) 29 5 Core Principles 71 Building a Strong Competitive Economy 71 Ensuring the Vitality of Town Centres 78 Supporting a Prosperous Rural Economy 85 Delivering a Wide Choice of High Quality Homes 98 Protecting Green Belt Land 124 Sustainable Transport 127 Supporting High Quality Infrastructure 138 Requiring Good Design 150 Promoting Healthy Communities 158 Meeting the Challenge of Climate Change, Flooding and Coastal Change 167 Conserving and Enhancing the Natural and Historic Environment 185 Minerals and Waste 212 Appendices A Strategic Policies 259 B Table of Superseded Policies 261 C Coal Mining Risk Assessments, Minerals Assessments and Minerals and/or Waste 262 Infrastructure Assessment D Safeguarding Mineral Resources and Safeguarded Minerals and Waste Sites 270 E Glossary of Terms 279 CDP Adopted Version 2020 Contents List of County Durham Plan Policies Policy 1 Quantity of New Development 20 Policy 2 Employment Land 30 Policy 3 Aykley Heads 38 Policy 4 Housing Allocations 47 Policy 5 Durham City's Sustainable Urban Extensions 61 Policy 6 Development on Unallocated Sites 68 Policy 7 Visitor Attractions -

Hamsterley Forest 1 Weardalefc Picture Visitor Library Network / John Mcfarlane Welcome to Weardale

Welcome to Weardale Things to do and places to go in Weardale and the surrounding area. Please leave this browser complete for other visitors. Image : Hamsterley Forest www.discoverweardale.com 1 WeardaleFC Picture Visitor Library Network / John McFarlane Welcome to Weardale This bedroom browser has been compiled by the Weardale Visitor Network. We hope that you will enjoy your stay in Weardale and return very soon. The information contained within this browser is intended as a guide only and while every care has been taken to ensure its accuracy readers will understand that details are subject to change. Telephone numbers, for checking details, are provided where appropriate. Acknowledgements: Design: David Heatherington Image: Stanhope Common courtesy of Visit England/Visit County Durham www.discoverweardale.com 2 Weardale Visitor Network To Hexham Derwent Reservoir To Newcastle and Allendale Carlisle A69 B6295 Abbey Consett River Blanchland West Muggleswick A 692 Allen Edmundbyers Hunstanworth A 691 River Castleside East Allen North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Lanchester A 68 B6278 C2C C2C Allenheads B6296 Heritage C2C Centre Hall Hill B6301 Nenthead Farm C2C Rookhope A 689 Lanehead To Alston Tunstall Penrith Cowshill Reservoir M6 Killhope Lead Mining The Durham Dales Centre Museum Wearhead Stanhope Eastgate 3 Ireshopeburn Westgate Tow Law Burnhope B6297 Reservoir Wolsingham B6299 Weardale C2C Frosterley N Museum & St John’s Chapel Farm High House Trail Chapel Weardale Railway Crook A 689 Weardale A 690 Ski Club Weardale -

Ennerdale and Kinniside Community Led Plan Questionnaire

Ennerdale and Kinniside Community Led Plan Questionnaire Ref No. Community Led Planning This extract, from ACTion with Communities in Cumbria The Planning Group is responsible for developing the Guidance Sheet, explains what community led planning plan, including action plans, while the Parish Council is: will ensure that action plans are being worked towards, monitoring progress on the action plans. ‘A Community Led Plan (CLP) is a plan for the community, by the community. The Parish Council will need to prepare or up-date the community led plan every five years. The plan can be ‘It sets out a vision for the future based on widespread local used by community groups and businesses to consultation, with actions for how this can be achieved. demonstrate support or need for projects/activities, when applying for funding. ‘CLPs can cover anything the community feels is important to them, from more notice boards around the We aim to prepare a plan that reflects the views and village, through to the creation of affordable wishes of parish residents. We want everyone who lives housing. in the parish to feel that the plan belongs to them, and we hope that those of you who have an interest in a ‘Community Led Planning produces an action plan particular issue will get involved in the relevant actions. owned and delivered by the community, with support as appropriate from local authorities and other agencies. Some of the actions will fall within the responsibility of ‘CLPs are usually initiated by the Parish Council and can the Parish Council, while others will need to involve or cover one or more parishes.’ be referred on to other agencies, e.g. -

West Cumbria: Opportunities and Challenges 2019 a Community Needs Report Commissioned by Sellafield Ltd

West Cumbria: Opportunities and Challenges 2019 A community needs report commissioned by Sellafield Ltd February 2019 2 WEST CUMBRIA – OPPORTUNITIES & CHALLENGES Contents Introduction 3 Summary 4 A Place of Opportunity 6 West Cumbria in Profile 8 Growing Up in West Cumbria 10 Living & Working in West Cumbria 18 Ageing in West Cumbria 25 Housing & Homelessness 28 Fuel Poverty 30 Debt 32 Transport & Access to Services 34 Healthy Living 36 Safe Communities 42 Strong Communities 43 The Future 44 How Businesses Can Get Involved 45 About Cumbria Community Foundation 46 WEST CUMBRIA – OPPORTUNITIES & CHALLENGES 3 Introduction Commissioned by Sellafield Ltd and prepared by Cumbria Community Foundation, this report looks at the opportunities and challenges facing communities in West Cumbria. It provides a summary of the social needs and community issues, highlights some of the work already being done to address disadvantage and identifies opportunities for social impact investors to target their efforts and help our communities to thrive. It is an independent report produced by Cumbria We’ve looked at the evidence base for West Community Foundation and a companion document Cumbria and the issues emerging from the statistics to Sellafield Ltd’s Social Impact Strategy (2018)1. under key themes. Our evidence has been drawn from many sources, using the most up-to-date, Cumbria Community Foundation has significant readily available statistics. It should be noted that knowledge of the needs of West Cumbria and a long agencies employ various collection methodologies history of providing support to address social issues and datasets are available for different timeframes. in the area. -

Apr 20 Contact

Published by the Church Council for Lamplugh, Kirkland and Ennerdale Ecumenical Parish One parish, three beautiful churches April 2020 page 1 Church Officers and Contacts Minister: Rev Ian Parker, 01946 861310, E-mail: [email protected] [Thursday is Ian’s day off] Worship Leader: Pam Carter. tel: 862329. Mob: 07545220617 E-mail: [email protected] The Vicarage, Arlecdon, Frizington, CA26 3UB. Secretary: Mr Michael Watts 861856 E-mail: [email protected] Treasurer: Mr D Beak 861822 Gift Aid Manager: Mrs M Abbot 861963 Deanery Synod: Mrs M Abbot and Mr H Smith Methodist Minister: Rev Paul Saunders 01900 823273 Western Fells Office: 01946 812880 Editor of contact: Mr Michael Watts 861856 E-mail: [email protected] Church Wardens:Mr R Megan 862904 Mr C Atkinson 862327 Electoral Roll: Mr C Atkinson 862327 Little Church: Chris Murphy 862449 Bible Study & Christian Fellowship : Minister Messy Church Club: Dorothy Nevinson C/o Minister i) Diocesan website: http://www.carlislediocese.org.uk ii) The National Churches Trust website: https://www.explorechurches.org/church/st-michael-all-angels-lamplugh https://www.explorechurches.org/church/st-mary-ennerdale-bridge iii) http://www.achurchnearyou.com Community contacts Borough Councillor: Gwyneth Everett e-mail: Gwyneth.Everett@@Copeland.gov.uk Borough Councillor: Steve Morgan e-mail: [email protected] County Councillor: Arthur Lamb tel: 07795 169595 e-mail: [email protected] LAMPLUGH PARISH COUNCIL John Sloan, High Mill Barn, High Lorton, CA13 9UB tel:01900 85833 EXECUTIVE HEADTEACHER 861386 ASSISTANT HEADTEACHER 861386 [email protected] CHAIR OF GOVERNORS Mr Andy Pratt email [email protected] c/o 861386 SCHOOL LSA Chair Amy Donohoe 07979254917 Secretary Laura Thompson, c/o school 861386 SPORTS COMMITTEE Guy Murray 862461 YOUNG FARMERS Mr B Wilson, Dockray Nook, Lamp. -

Copeland Borough Council

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW SUBMISSION ON WARDING ARRANGEMENTS EXECUTIVE MEMBER: Councillor David Moore LEAD OFFICER: Pat Graham, Managing Director REPORT AUTHOR: Tim Capper, Boundary Review Project Officer SUMMARY: Seeks agreement from Council to a submission to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England on warding and boundary arrangements in connection with the current review of the Council’s electoral arrangements RECOMMENDATIONS: That the wards and boundaries as set out in Appendix “A” and the accompanying plans be approved as the Council’s submission to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England in this phase of the review 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Council at its meeting on 1 October 2015 agreed to ask the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) to review the electoral arrangements of the Council. 1.2 LGBCE has already determined in the preliminary phase of the review that the total number of Councillors to be elected to the Council in future (Council size) will be 33. The present phase of the review will determine new ward boundaries, the number of Councillors to be elected for each ward, and ward names. LGBCE has invited the Council to submit proposals to them on warding by 12 February 2018, along with a wide range of other local stakeholders including, for example, parish councils. 2 WARDING – STATUTORY CRITERIA 2.1 In considering warding arrangements, Members need to be aware of the statutory criteria by which LGBCE are bound in deciding on warding arrangements. These are: Delivering electoral equality for local voters – meaning ensuring that each councillor represents roughly the same number of electors so that the value of the elector’s vote is the same regardless of where in the Borough an elector lives. -

The Way of Life Route Description

1 Introduction This first draft gives directions for travelling The Way of Life from Gainford to Durham. Where there is a heading in red is where there either is now or will be some extra information about a particular location. Distances are approximate. The total distance is 47 Kilometres or 29 miles. I have divided the route into 4 sections between 11 and 14 kilometres. Section 1 Gainford to West Auckland 11 km Gainford Gainford is an ancient site. There was a Saxon church here in the 8th century. The presence of St Mary’s Well on the south side of the present church facing the river is significant, because the early Christians often chose and cleansed sites formerly associated with pagan devotion, which often centred on springs or water courses. Fragments of Anglo-Saxon sculpture found inside and around the church are further evidence that an ancient Christian community existed on this site, whilst sculpture combining Northumbrian and Norse motifs reflects subsequent Scandinavian settlement in the region. These sculptures are to be found in the Open Treasure exhibition at Durham Cathedral. As the earliest church in the area, St Mary's Church is fondly regarded as 'the Mother Church of Teesdale'. The first written evidence of Gainford was produced by Simeon of Durham who tells us that Eda or Edwine, a Northumbrian chief who had exchanged a helmet for a cowl, died in 801 and was buried in the monastery at Gegenforda. There are records giving evidence to Gainford having been part of the Northumbrian Congregation of Cuthbert of Lindisfarne in Saxon times. -

Stage 5. Sedgefield to Durham Cathedral

Stage 5 - SEDGEFIELD to DURHAM CATHEDRAL Distance - 21.4 km / 13.2 miles Explorer maps - Bishop Auckland - 305, Durham & Sunderland 308 Time - 5.5 - 6 hours average time based on Naismith’s rule Total ascent - 170m Total descent - 219m Description - This is a pleasant stage that follows and old disused railway line and fields to the medieval village of Coxhoe. Walk along the main street and then across the A1/M motorway and another disused railway line. Continue on farm tracks and fields before descending through the woods to reach the river Wear and the Weardale Way to Durham 1 - From the square turn right and left through the hotel archway to reach a T-junction. Continue ahead on the footpath through the field and then turn left, straight ahead (ignore left path) to reach the main road. Cross over into Hardwick Hall grounds and bear right, signed Conference & Banqueting. 2 - Continue on the track past the hotel on the left, ignore the track right after passing the farm buildings. Just before the farm house turn left onto the footpath to pass a wooded area on the right and then one on the left. At the end reach a bridleway T-junction. Turn right signed Bishop Middleham 1.5 miles to reach a disused railway line. 3 - Cross over the railway line and continue ahead and at the pond keep left with a stone wall on the left to reach the edge of a hill with the village below. Turn left and go around the hill and left down the side of it to reach a stile on the left. -

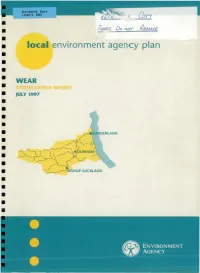

Display PDF in Separate

local environment agency plan WEAR CONSULTATION REPORT JULY 1997 YO UR V IE W S Welcome to the Consultation Report for the Wear area which is the Agency's initial analysis of the status of the environment in this area and the issues that we believe need to be addressed. W e would like to hear your views: • Have we identified all the major issues? • Have we identified realistic proposals for action? • Do you have any comments to make regarding the Consultation Report in general? • Have you any other comments? During the consultation period for this report the Agency would be pleased to receive any comments in writing to: Environment Planner The Environment Agency Northumbria Area Tyneside House Newcastle Business Park Newcastle Upon Tyne NE4 7AR All comments must be received by 31 October 1997 Further copies of the document can be obtained from the above address. All comments received will be considered in preparing the next phase, the Action Plan. The Action Plan will build upon Section 1 of this Consultation Report by turning the proposals into actions. Note: Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this Report it may contain some errors or omissions which we will be pleased to note ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 116604 How to use this Consultation Report The publication of this Consultation Report is an important stage in the Environment Agency's local planning process. The aim of the process is to identify, prioritise and cost environmentally beneficial actions which the Agency and others will work together to deliver within the Wear area. -

Newman, C.E. 2014 V.1.Pdf

Mapping the Late Medieval and Post Medieval Landscape of Cumbria Two Volumes Volume 1: Text Caron Egerton Newman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Classics and Archaeology Newcastle University Submitted: June 2014 Abstract This study is an analysis of the development of rural settlement patterns and field systems in Cumbria from the later medieval period through to the late eighteenth century. It uses documentary, cartographic and archaeological evidence. This evidence is interpreted utilising the techniques of historic landscape characterisation (HLC), map regression and maps created by the author, summarising and synthesising historical and archaeological data. The mapped settlement data, in particular, has been manipulated using tools of graphic analysis available within a Graphical Information System (GIS). The initial product is a digital map of Cumbria in the late eighteenth century, based on the county-scale maps of that period, enhanced with information taken from enclosure maps and awards, and other post medieval cartographic sources. From this baseline, an interpretation of the late medieval landscape was developed by adding information from other data sources, such as place names and documentary evidence. The approach was necessarily top-down and broad brush, in order to provide a landscape-scale, sub-regional view. This both addresses the deficiencies within the standard historical approach to landscape development, and complements such approaches. Standard historical approaches are strong on detail, but can be weak when conclusions based on localised examples are extrapolated and attributed to the wider landscape. The methodology adopted by this study allows those local analyses to be set within a broader landscape context, providing another tool to use alongside more traditional approaches to historic landscape studies. -

The Way of Learning

1 JARROW TO DURHAM Introduction This guide describes the pilgrimage route between St Paul’s Church in Jarrow and Durham Cathedral. All the Northern Saints Trails use the same waymark shown on the left. The route also follows Bede’s Way from Jarrow to Monkwearmouth, The Weardale Way from New Lambton to Durham and Cuddy’s Corse from Chester-le-Street to Durham, so those way marks will also be helpful. The route is 61 kilometres or 38 miles. It is the most urban of the routes with two thirds of the route on minor roads or paved paths, but it is a route full of interest. I have divided the route into 5 sections of between 10 to 17 kms in length. Points of interest are described in red. The primary focus for the majority of pilgrims journeying to Durham Cathedral in the Middle Ages was the shrine of St Cuthbert, but the other most notable person, whose tomb is in the the Galilee Chapel in the cathedral, is the Venerable Bede. It is primarily because of him that this route is called The Way of Learning. He was indeed a man of great learning, who is probably best known for writing the first history of England. It was called An Ecclesiastical History of the English Speaking People. His other talents included the fact that was that he was an accomplished linguist, an astronomer and he also popularised measuring time from the birth of Christ. During his long life of extraordinary scholarship, he wrote 60 books. There are other connections with the theme of learning, apart from Bede, along the route.