Newman, C.E. 2014 V.1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Year Housing Land Supply As of 31 March 2019

Five Year Housing Land Supply as of 31st March 2019 1.0 Housing Requirement 1.1 Due to the under delivery of houses in Allerdale (for the areas outside the Lake District National Park Authority) (see Table 1), the Council considers it prudent that a 5% buffer is applied to the annual housing target, consistent with the Housing Delivery Test. The shortfall of dwellings will be addressed in the short term and therefore this buffer has been added to the five year land supply target in full, as per the Sedgefield method. Monitoring Period Net completions Local Plan Target Cumulative shortfall 2011/2012 201 304 -103 2012/2013 189 304 -218 2013/2014 196 304 -326 2014/2015 300 304 -330 2015/2016 385 304 -249 2016/2017 250 304 -303 2017/2018 480 304 -127 2018/2019 337 304 -94 Total 2,338 2,432 -94 Table 1: Net housing completions since 1st April 2011 1.2 Therefore the annual housing requirement for the next 5 years is 339 dwellings per annum (see Table 2). Housing target April 2018-March 2023 1,520 (304 x 5) Housing Shortfall (1st April 2011 – 1st April 2018) -94 Housing Requirement April 2011-March 2024 (5% buffer 1,695 applied to target and shortfall) Annualised Housing Requirement (1695/5) 339 Table 2: Calculating the annual housing requirement 2.0 Housing Supply 2.1 Allerdale Borough Council’s housing supply has been calculated with the following categories (Table 3): • Large sites with planning permission (10 dwellings or more) (see Appendix A) • Small sites with planning permission (9 dwellings or less) (see Appendix B) • Sites with resolution to grant planning permission subject to a s106 Agreement being signed (see Appendix C) 2.2 Appendix D includes details of sites which support windfall allowance of 30 dwellings per annum. -

Proceedings W Esley Historical Society

Proceedings OF THE W esley Historical Society Editor: REv. JOHN C. BOWMER, M.A., B.D., Ph.D. Volume XL June 1975 JOHN WESLEY, LITERARY ARBITER An Introduction to his use of the Asterisk EADERS turning to the edition of his Works published by John Wesley in thirty-two volumes during the years 1771-4 R may naturally be surprised to find him deserting his normal custom (and the normal custom of the century) of using asterisks as the primary means for directing attention to footnotes. Instead he employs daggers, double daggers, parallel lines, the section mark, the paragraph symbol, but only occasionally asterisks, and then ob viously in error.1 On the other hand, the curious reader will also be surprised from time to time to discover that many paragraphs begin with an asterisk. If his curiosity is sufficiently aroused, he may turn to the preface in volume i to discover what Wesley was about. He might also wish to know when W esley began this practice, how fully he carried it out, and upon what principles. Perhaps he would also wonder whether this unusual feature was in fact unique. Wesley was in fact indicating purple passages. He may have derived the idea from Alexander Pope, who prefaced his edition of Shakespeare's works by pointing out: Some of the most shining passages are distinguished by con~mas in the margin; and where the beauty lay not in particulars but in the whole, a star is prefixed to the scene. Pope continued : This seems to me a shorter and less ostentatious method of performing the better half of criticism (namely the pointing out an author's excel lencies) than to fill a whole page with citations of fine passages, with general applauses, or empty exclamations at the tail of them.2 There is no certainty which edition (or editions) of Shakespeare Wesley used, but his diary shows him reading several of the tragedies and histories in 1726-the year after Pope's edition was published. -

Allerdale Local Plan (Part 1)

Allerdale Borough Council Allerdale Local Plan (Part 1) Strategic and Development Management Policies July 2014 www.allerdale.gov.uk/localplan Foreword To meet the needs of Allerdale’s communities we need a plan that provides for new jobs to diversify and grow our economy and new homes for our existing and future population whilst balancing the need to protect the natural and built environment. This document, which covers the area outside the National Park, forms the first part of the Allerdale Local Plan and contains the Core Strategy and Development Management policies. It sets a clear vision, for the next 15 years, for how new development can address the challenges we face. The Core Strategy will guide other documents in the Allerdale Local Plan, in particular the site allocations which will form the second part of the plan. This document is the culmination of a great deal of public consultation over recent years, and extensive evidence gathering by the Council. The policies in the Plan will shape Allerdale in the future, helping to deliver sustainable economic development, jobs and much needed affordable housing for our communities. Councillor Mark Fryer Economic Growth Portfolio holder Contents What is the Allerdale Local Plan? ......................................................................... 1 What else is it delivering? ..................................................................................... 6 Spatial Portrait ..................................................................................................... -

SWARTHMOOR Wwtw, ULVERSTON, Cumbria

SWARTHMOOR WwTW, ULVERSTON, Cumbria Archaeological Watching Brief - Supplementary Report Oxford Archaeology North December 2009 United Utilities Issue No: 2009-10/1004 OA North Job No: L9355 NGR: SD 2788 7787 Swarthmoor WwTW, Ulverston, Cumbria: Archaeological Watching Brief - Supplementary Report 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 3 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Circumstances of the Project ........................................................................... 4 2. METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Project Design................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Watching Brief................................................................................................ 5 2.3 Archive........................................................................................................... 5 3. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Location, Topography and Geology ................................................................ 6 3.2 Historical and Archaeological Background..................................................... -

1 Written Description of the Boundary Relating to the Yorkshire Dales National Park

Written Description of the Boundary relating to the Yorkshire Dales National Park (Designation) (Variation) Confirmation Order 2015 Introduction This description is designed to be read in conjunction with the 1:25,000 scale maps included within the Yorkshire Dales National Park (Designation) (Variation) Confirmation Order 2015 as confirmed by the Secretary of State on 23rd day of October 2015. It does not form part of the Order but is intended to assist interpretation of the map against features on the ground. Map references in italics refer to the map numbers in the top right corner of the maps bound in with the Order. Map references within the text e.g. SD655749 are six figure Ordnance Survey Grid References. The description of the boundary proceeds round the area of the boundary variations in a clockwise direction (in line with the direction of the text in the original boundary description which accompanied the 1953 Yorkshire Dales National Park Designation Order), from the point at which it deviates from the original boundary, to the point at which it re-joins it. In line with the description of the 1953 boundary, and unless otherwise stated: where the boundary follows roads and tracks, it follows the edge of the metalled surface of the road and the edge of the track, excluding the roads and tracks themselves (there are some exceptions, as stated below); and in the case of water courses, if it is not stated whether the boundary follows the edge or the centre, the boundary follows the centre of the water course (although in this description the edge of water courses is generally stated). -

Letter Re Planning Application for 9 Houses Dec 2016

DRAUGHTON PARISH COUNCIL The Pines Draughton Skipton BD23 6DU 2 January 2017 Development Control Services Craven District Council 1 Belle Vue Square Skipton BD23 1FJ Attn: Ms G Kennedy Dear Sirs Application Ref: 24/2016/17616 – Land at Draughton off access road to A65 Thank you for consulting us on the above planning application, which concerns a proposed development for 9 residential dwellings off the old A65 in Draughton parish. We object to this development for the reasons set out below. Summary The area of proposed development is a field sloping down from the old A65 road into the village to the tree lined Howgill Beck below, a tributary of the River Wharfe. It is currently used as grazing land. Draughton is a small attractive village, typical of the Yorkshire Dales, with stone built properties and dry stone walls much in evidence. Its pattern of settlement is tightly knit, having been strongly influenced by the steep contours created by the valley formed by Howgill Beck. The scenic Dales landscape surrounding the village is a key feature in its setting, and one which is recognised by the widely- drawn conservation area boundary. These are the main attributes from which the locality derives its character and appearance. Against this background, there are no sites included as preferred options for housing development in Draughton in the draft Local Plan. Draughton is not regarded as a sustainable location for growth because of the lack of local amenities, facilities and infrastructure. This development will not bring any further facilities or infrastructure into the village; it will only put greater strain on the existing, very limited facilities. -

Rural Wheels Service on 0845 602 3786 Or Email: [email protected]

If you live within the rural areas of South Lakeland district shown below and outside the town boundaries of Ulverston, Windermere including Bowness-on- Windermere and Kendal then you are eligible to join Rural Wheels. You may use the service if you do not have access to public transport. Rural Wheels can be used to link you up with the bus or train, or take you to your nearest town to access shops, attend appointments etc. South Lakeland Rural Wheels Designated Area Retailers within South Lakeland You can purchase more points for your Rural Wheels card with the Transport Provider or alternatively at the Retailer outlets below, you can purchase in amounts of £5, £10 or £20 at a time: Ambleside Library, Kelsick Road, Ambleside , 015394 32507 Grange-over-Sands Library , Grange Fell Road, Grange-over-Sands, 01539 532749 Greenodd Post Office , Main Street, Greenodd, 01229 861201 Grizebeck Service Station , Grizebeck, Kirkby-in-Furness, 01229 889259 Kendal Library, Stricklandgate, Kendal, 01539 773520 Kirkby Lonsdale Post Office, 15 New Road, Kirkby Lonsdale, 015242 71233 Milnthorpe Post Office, 10 Park Road, Milnthorpe 015395 63134 Ulverston Library , Kings Road, Ulverston, 01229 894151 Windermere Library , Ellerthwaite, Windermere, 01539 462400 The Mobile Library—across South Lakes District Card top ups are also available by post: Send your Rural Wheels Card and a cheque/postal order payable to Cumbria County Council to : Rural Wheels, Environment, Transport, The Courts, Carlisle, CA3 8NA If you have any enquiries about Rural Wheels, please see our colour leaflet, or contact the Rural Wheels Service on 0845 602 3786 or email: [email protected] . -

Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner for Cumbria - Pcc Expenses

OFFICE OF THE POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER FOR CUMBRIA - PCC EXPENSES Name: Peter McCall Month: January 2018 Date Reason/Event Location Mode of Cost Accommodation Other Total Travel 30/01/2018 – NCA meeting London Train £107.00 VSC £102.50 Tube £12.70 £275.85 31/01/2018 Tube £12.70 M&S £16.95 Car Park £24.00 Total £107.00 £102.50 £66.35 £275.85 OFFICE OF THE POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER FOR CUMBRIA - PCC EXPENSES Name: Peter McCall Month: February 2018 Date Reason/Event Location Mode of Cost Accommodation Other Total Travel Total Nil Return Nil Return Nil Return Nil Return OFFICE OF THE POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER FOR CUMBRIA - PCC EXPENSES Name: Peter McCall Month: March 2018 Date Reason/Event Location Mode of Cost Accommodation Other Total Travel 19/01/2018 Penrith Show Ainstable Own 33 miles @ 44 £14.52 Annual Dinner vehicle ppm £14.52 06/02/2018 Internet Safety Day Cockermouth Own 51 miles @ 44 £22.44 at Cockermouth vehicle ppm £22.44 School 07/02/2018 Meet the Police Carlisle Own 36 miles @ 44 £15.84 event in Carlisle vehicle ppm £15.84 13/02/2018 U3A Speaking Ulverston Pool car Car park £3.20 £3.20 Engagement 15/02/2018 Army Cadets event Cockermouth Own 52 miles @ 44 £22.88 vehicle ppm £22.88 22/02/2018 Attend Operation Longtown Own 53 miles @ 44 £23.32 ‘Running Bear’ vehicle ppm £23.32 12/03/2018 Meetings with Carlisle Pool car Car park £ 1.90 £1.90 Cumbria County Council and Carlisle City Council 15/03/2018 Visit Cockermouth Cockermouth Own 52 miles @ 44 Car park £1.20 £24.08 Mountain Rescue vehicle ppm £22.88 22/03/2018 Media -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

North West Inshore and Offshore Marine Plan Areas

Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Marshall Paul Macrae 1.0 Paul Macrae Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Paul Macrae Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

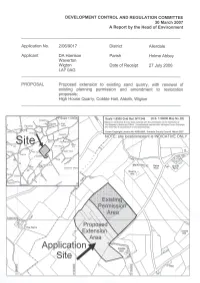

(Item 9) Application No. 2-06-9017 High House Quarry, Cobble Hall

1.0 RECOMMENDATION 1.1 That having regard to the environmental information planning permission be GRANTED for the reasons set out in Appendix 1 and subject to: (a) The execution of an agreement under Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 to: (i) secure the proposed voluntary HGV routing agreement and ‘Haulier Rules’ which all the applicant’s drivers and haulage contractors are required to abide by; (ii) secure a contribution of £10,000 from the applicant to the Council which shall be applied by the Council to mitigate the impacts of HGV traffic and provide local highway improvements; (iii) secure the route of an access along the Abbeytown ridge top on land in the applicants ownership for recreational use. (b) The conditions in Appendix 2. 1.2 That the planning assessment set out in section 4 of the report shall form the basis of the statutory requirement to be published under Regulation 21 of the Town and Country Planning Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations 1999. 2.0 THE PROPOSAL 2.1 The applicant seeks to extend the life of an existing permission Ref. 2/01/9043 which expired on 31 December 2006 and extend the area of the sand quarry to the west by a further 10.7 hectares making a total site area of 19.6 hectares. 2.2 The High House Quarry is located at the eastern end of the fluvio-glacial sand ridge called the Abbeytown Ridge. Sand has been extracted from the area for 40 years and High House Quarry has been worked for 20 years in association with Aldoth and Dixon Hill Quarries, which are now worked out.